The Tempest

Play by William Shakespeare From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Tempest is a play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1610–1611, and thought to be one of the last plays that he wrote alone. After the first scene, which takes place on a ship at sea during a tempest, the rest of the story is set on a remote island, where Prospero, a magician, lives with his daughter Miranda, and his two servants: Caliban, a savage monster figure, and Ariel, an airy spirit. The play contains music and songs that evoke the spirit of enchantment on the island. It explores many themes, including magic, betrayal, revenge, forgiveness and family. In Act IV, a wedding masque serves as a play-within-a-play, and contributes spectacle, allegory, and elevated language.

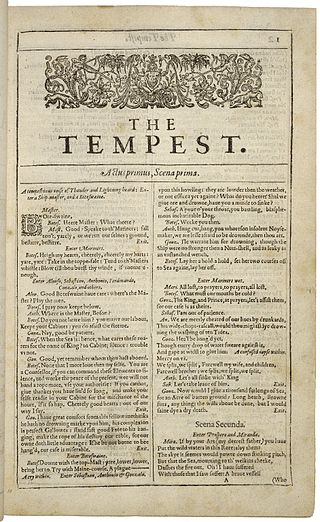

Title page of the part in the First Folio | |

| Editors | Edward Blount and Isaac Jaggard |

|---|---|

| Author | William Shakespeare |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Shakespearean comedy Tragicomedy |

| Publication place | England |

Although The Tempest is listed in the First Folio as the first of Shakespeare's comedies, it deals with both tragic and comic themes, and modern criticism has created a category of romance for this and others of Shakespeare's late plays. The Tempest has been widely interpreted in later centuries. Its central character Prospero has been identified with Shakespeare - and Prospero's renunciation of magic signaling Shakespeare's farewell to the stage. And it has been seen as an allegory of Europeans colonizing foreign lands.

The play has had a varied afterlife, inspiring artists in many nations and cultures, on stage and screen, in literature, music (especially opera), and the viaual arts.

Characters

- Prospero – the rightful Duke of Milan and a magician

- Miranda – daughter to Prospero

- Ariel – a spirit in service to Prospero

- Caliban – an enslaved servant of Prospero

- Alonso – King of Naples

- Sebastian – Alonso's brother

- Antonio – Prospero's brother, the usurping Duke of Milan

- Ferdinand – Alonso's son

- Gonzalo – an honest old councillor

- Adrian – a lord serving under Alonso

- Francisco – a lord serving under Alonso

- Trinculo – the King's jester

- Stephano – the King's drunken butler

- Juno – Roman goddess of marriage

- Ceres – Roman goddess of agriculture

- Iris – Greek goddess of the rainbow and messenger of the gods

- Master – master of the ship

- Mariners

- Boatswain – servant of the master

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

Act I

Twelve years before the action of the play, Prospero, formerly Duke of Milan and a gifted sorcerer, had been usurped by his treacherous brother Antonio with the aid of Alonso, King of Naples. Escaping by boat with his infant daughter Miranda, Prospero flees to a remote island where he has been living ever since. There he used his magic to force the island's only inhabitant, Caliban, to protect him and Miranda. He also frees the spirit Ariel and binds them into servitude.

When a ship carrying his brother Antonio passes nearby, Prospero conjures up a storm with help from Ariel and the ship is destroyed. Antonio is shipwrecked, along with Alonso, Ferdinand (Alonso's son and heir to the throne), Sebastian (Alonso's brother), Gonzalo (Prospero's trustworthy minister), Adrian, and other court members.

Acts II and III

Prospero enacts a sophisticated plan to take revenge on his usurpers and regain his dukedom. Using magic, he separates the shipwreck survivors into groups on the island:

- Ferdinand, who is rescued by Prospero and Miranda and given shelter. Prospero successfully manipulates the youth into a romance with Miranda;

- Trinculo, the king's jester, and Stephano, the king's drunken majordomo, who encounter Caliban. Recognizing his miserable state, the three stage an unsuccessful "rebellion" against Prospero. Their actions provide the comic relief of the play.

- Alonso, Sebastian, Antonio, Gonzalo, and two attendant lords (Adrian and Francisco). Antonio and Sebastian conspire to kill Alonso and Gonzalo so Sebastian can become King; Prospero and Ariel thwart the conspiracy. Later, Ariel takes the form of a harpy and torments Antonio, Alonso, and Sebastian, causing them to flee in guilt for their crimes against Prospero and each other.

- The ship's captain and boatswain, along with the other surviving sailors, are placed into a magical sleep until the final act.

Act IV

Prospero intends that Miranda, now aged 15, will marry Ferdinand, and he instructs Ariel to bring some other spirits and produce a masque. The masque will feature classical goddesses, Juno, Ceres, and Iris, and will bless and celebrate the betrothal. The masque will also instruct the young couple on marriage, and on the value of chastity until then.

The masque is suddenly interrupted when Prospero realises he had forgotten the plot against his life. Once Ferdinand and Miranda are gone, Prospero orders Ariel to deal with the nobles' plot. Caliban, Trinculo, and Stephano are then chased off into the swamps by goblins in the shape of hounds.

Act V and Epilogue

Prospero vows that once he achieves his goals, he will set Ariel free, and abandon his magic, saying:

I'll break my staff,

Bury it certain fathoms in the earth,

And deeper than did ever plummet sound

I'll drown my book.[1]

Ariel brings on Alonso, Antonio, and Sebastian. Prospero forgives all three. Prospero's former title, Duke of Milan, is restored. Ariel fetches the sailors from the ship, and then Caliban, Trinculo, and Stephano. Caliban, seemingly filled with regret, promises to be good. Stephano and Trinculo are ridiculed and sent away in shame by Prospero. Before the reunited group (all the noble characters with the addition of Miranda and Prospero) leave the island, Ariel is instructed to provide good weather to guide the king's ship back to the royal fleet and then to Naples, where Ferdinand and Miranda will be married. After this, Ariel is set free.

In an epilogue, Prospero requests that the audience set him free — with their applause.

The masque

Summarize

Perspective

The Tempest begins with the spectacle of a storm-tossed ship at sea, and later there is a second spectacle—the masque. A masque in Renaissance England was a festive courtly entertainment that offered music, dance, elaborate sets, costumes, and drama. Often a masque would begin with an "anti-masque", that showed a disordered scene of satyrs, for example, singing and dancing wildly. The anti-masque would then be dramatically dispersed by the spectacular arrival of the masque proper in a demonstration of chaos and vice being swept away by glorious civilisation. In Shakespeare's play, the storm in scene one functions as the anti-masque for the masque proper in act four.[2][3][4]

The masque in The Tempest is not an actual masque; rather, it is an analogous scene intended to mimic and evoke a masque, while serving the narrative of the drama that contains it. The masque is a culmination of the primary action in The Tempest: Prospero's intention to not only seek revenge on his usurpers, but to regain his rightful position as Duke of Milan. Most important to his plot to regain his power and position is to marry Miranda to Ferdinand, heir to the King of Naples. This marriage will secure Prospero's position by securing his legacy. The chastity of the bride is considered essential and greatly valued in royal lineages. This is true not only in Prospero's plot, but also notably in the court of the virgin queen, Elizabeth. Sir Walter Raleigh had in fact named one of the new world colonies "Virginia" after his monarch's chastity. It was also understood by James, king when The Tempest was first produced, as he arranged political marriages for his grandchildren. What could possibly go wrong with Prospero's plans for his daughter is nature: the fact that Miranda is a young woman who has just arrived at a time in her life when natural attractions among young people become powerful. One threat is Caliban, who has spoken of his desire to rape Miranda, and "people ... this isle with Calibans",[5] and who has also offered Miranda's body to a drunken Stephano.[6] Another threat is represented by the young couple themselves, who might succumb to each other prematurely. Prospero says:

Look thou be true. Do not give dalliance

Too much the rein. The strongest oaths are straw

To th'fire i'th'blood. Be more abstemious

Or else good night your vow![7]

The need to teach Miranda is what inspires Prospero in act four to create the masque, and the "value of chastity" is a primary lesson being taught by the masque along with having a happy marriage.[8][failed verification][9][10]

Date and sources

Summarize

Perspective

Date

It is not known for certain exactly when The Tempest was written, but evidence supports the idea that it was probably composed sometime between late 1610 to mid-1611. [11][12] Evidence supports composition perhaps occurring before, after, or at the same time as The Winter's Tale.[11] It is considered one of the last plays that Shakespeare wrote alone. But it was not, as is sometimes claimed, Shakespeare's last play, since it is post-dated by his collaborations with John Fletcher: Henry VIII, Cardenio and The Two Noble Kinsmen.[13] Edward Blount entered The Tempest into the Stationers' Register on 8 November 1623. It was one of 16 Shakespeare plays that Blount registered on that date.[14]

Sources

There is no obvious single source text for the plot of The Tempest: it appears to have been created by Shakespeare with several sources contributing. [15]

The Sea Venture: William Strachey's A True Reportory of the Wracke and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight, an eyewitness report of the real-life shipwreck of the Sea Venture in 1609 on the island of Bermuda while sailing toward Virginia, may be considered a primary source for the opening scene, as well as a few other references in the play to conspiracies and retributions.[16] Although not published until 1625, Strachey's report was first recounted in his "Letter to an Excellent Lady", a private letter describing the incident and the earliest account of all. It was dated 15 July 1610, and it is thought that Shakespeare - who had personal connections with a number of members of the Virginia Company - may have seen the original sometime during that year.[17][18] At around the time Shakespeare could have read Strachey's letter, another Sea Venture survivor, Silvester Jourdain, published his account, A Discovery of The Barmudas, otherwise Called the Ile of Divels.[19] Also there is the Council of Virginia's 1610 pamphlet True Declaration of the state of the Colonie in Virginia, with a confutation of such scandalous reports as have tended to the disgrace of so worthy an enterprise.[20] Regarding the influence of Strachey on the play, Kenneth Muir says that although "there is little doubt that Shakespeare had read ... William Strachey's True Reportory" and other accounts, "the extent of the verbal echoes of [the Bermuda] pamphlets has, I think, been exaggerated. There is hardly a shipwreck in history or fiction which does not mention splitting, in which the ship is not lightened of its cargo, in which the passengers do not give themselves up for lost, in which north winds are not sharp, and in which no one gets to shore by clinging to wreckage."[21]

Montagne's Of The Canibales: Gonzalo's description of his ideal society[22] thematically and verbally echoes Montaigne's essay Of the Canibales, translated into English in a version published by John Florio in 1603. Montaigne praises the society of the Caribbean natives: "It is a nation ... that hath no kinde of traffike, no knowledge of Letters, no intelligence of numbers, no name of magistrate, nor of politike superioritie; no use of service, of riches, or of poverty; no contracts, no successions, no dividences, no occupation but idle; no respect of kinred, but common, no apparrell but natural, no manuring of lands, no use of wine, corne, or mettle. The very words that import lying, falsehood, treason, dissimulation, covetousnes, envie, detraction, and pardon, were never heard of amongst them."[23]

Ovid's Metamorphoses: A source for Prospero's speech in act five, in which he bids farewell to magic[24] is an invocation by the sorceress Medea found in Ovid's poem Metamorphoses. Medea calls out:

Ye airs and winds; ye elves of hills, of brooks, of woods alone,

Of standing lakes, and of the night, approach ye every one,

Through help of whom (the crooked banks much wondering at the thing)

I have compelled streams to run clean backward to their spring.[25]

Shakespeare's Prospero begins his invocation:

Ye elves of hills, brooks, standing lakes and groves,

And ye that on the sands with printless foot

Do chase the ebbing Neptune, and do fly him

When he comes back ...[26][27]

Other Sources: Other shipwreck narratives probably drawn on by Shakespeare include those of Antonio Pigafetta contained in Richard Eden's travel anthologies of 1555 and 1557.[28] And some of the characters' names may derive from a 1594 History of Italy.[29]

The Tempest may take its overall structure from traditional Italian commedia dell'arte, which sometimes featured a magus and his daughter, their supernatural attendants, and a number of rustics. The commedia often featured a clown known as Arlecchino (or his predecessor, Zanni) and his partner Brighella, who bear a striking resemblance to Stephano and Trinculo; a lecherous Neapolitan hunchback who corresponds to Caliban; and the clever and beautiful Isabella, whose wealthy and manipulative father, Pantalone, constantly seeks a suitor for her, thus mirroring the relationship between Miranda and Prospero.[30] Other dramatic influences on Prospero's character include Greene's Friar Bacon, Marlowe's Dr. Faustus and Shakespeare's own Owen Glendower.[31] Bremo in Mucedorus may have influenced Caliban.[32]

Scholars have debated the influence of Virgil's Aeneid, which Robert Wiltenburg described as "the main source of the play ... not the source of the plot ... but the work to which Shakespeare is responding".[33]

Recently, scholars have also identified the influence on the Tempest of Marston's The Malcontent,[34] Beaumont and Fletcher's Philaster[34] and the anonymous romance Primaleon, Prince of Greece.[35]

Text

Summarize

Perspective

The Tempest first appeared in print in 1623 in the collection of 36 of Shakespeare's plays entitled, Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies; Published according to the True and Original Copies, which is known as the First Folio. The plays, including The Tempest, were gathered and edited by John Heminges and Henry Condell.[36]

The Folio text was based on a handwritten manuscript of The Tempest prepared by Ralph Crane, a scrivener employed by the King's Men. Crane probably copied from Shakespeare's rough draft, and based his style on Ben Jonson's Folio of 1616. Crane is thought to have neatened texts, edited the divisions of acts and scenes, and sometimes added his own improvements. He was fond of joining words with hyphens, and using elisions with apostrophes, for example by changing "with the king" to read: "wi'th' King".[37] The elaborate stage directions in The Tempest may have been due to Crane; they provide evidence regarding how the play was staged by the King's Men.[38]

The entire First Folio project was delivered to the blind printer, William Jaggard, and printing began in 1622. The Tempest is the first play in the publication. It was proofread and printed with special care; it is the most well-printed and the cleanest text of the thirty-six plays. To do the work of setting the type in the printing press, three compositors were used for The Tempest. In the 1960s, a landmark bibliographic study of the First Folio was accomplished by Charlton Hinman. Based on distinctive quirks in the printed words on the page, the study was able to individuate the compositors, and reveal that three compositors worked on The Tempest, who are known as Compositor B, C, and F. Compositor B worked on The Tempest's first page as well as six other pages. He was an experienced journeyman in Jaggard's printshop, who occasionally could be careless. In his role, he may have had a responsibility for the entire First Folio. The other two, Compositors C and F, worked full-time and were experienced printers.[36]

At the time, spelling and punctuation was not standardized and will vary from page to page, because each compositor had their individual preferences and styles. There is evidence that the press run was stopped at least four times, which allowed proofreading and corrections. However, a page with an error would not be discarded, so pages late in any given press run would be the most accurate, and each of the final printed folios may vary in this regard. This is the common practice at the time. There is also an instance of a letter (a metal sort or a type) being damaged (possibly) during the course of a run and changing the meaning of a word: After the masque Ferdinand says,

Let me live here ever!

So rare a wondered father and a wise

Makes this place paradise! (4.1.122–124)

The word "wise" at the end of line 123 was printed with the traditional long "s" that resembles an "f". But in 1978 it was suggested that during the press run, a small piece of the crossbar on the type had broken off, and the word should be "wife". Modern editors have not come to an agreement—Oxford says "wife", Arden says "wise".[39][40][41]

Themes and motifs

Summarize

Perspective

The Theatre

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air;

And like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

The Tempest is explicitly concerned with its own nature as a play, frequently drawing links between Prospero's art and theatrical illusion. The shipwreck was a spectacle that Ariel performed. [43] Prospero may even refer to the Globe Theatre when he describes the whole world as an illusion: "the great globe ... shall dissolve ... like this insubstantial pageant".[44] Ariel frequently disguises himself as figures from Classical mythology, for example a nymph, a harpy, and Ceres, acting as the latter in a masque that Prospero creates.[45]

Revenge and Forgiveness

The tone of Prospero's speech towards his three enemies Antonio, Alonso and Sebastian throughout the play is of rage and vengeance. However in the final act, Prospero tells Ariel "They being penitent, the sole drift of my purpose doth extend not a frown further."[46] But as Stephen Orgel notes in his introduction to the Oxford edition of the play, there is a condition in this speech which is not fulfilled: that Antonio is given no speech of remorse or contrition at the end of the play.[47]

Prospero freely forgives Alonso. But in his final speeches towards Antonio, Prospero's attitude vascillates: "You, brother mine, that entertained ambition ... I do forgive thee"[48] but then immediately reverses himself: "Unnatural though thou art!"[49] and reconsiders upon remembering the conspiracy to kill Alonso: "At this time I will tell no tales"[50] then almost reverses himself with: "Most wicked sir, whom to call brother would even infect my mouth"[51] and only then confirms his forgiveness, while giving Antonio no opportunity to repent: "I do forgive thy rankest fault - all of them; and require my dukedom of thee, which perforce I know thou must restore."[52][53]

The spareness of Shakespeare's writing in the last act give scope to the actor playing Prospero to decide whether it was always the intention to forgive his enemies or whether he is influenced by Ariel's advice to be "tender",[54] and similarly whether the change is gradual, is sudden, or is forced upon him by shame or expediency.[55]

Magic

Prospero has been described as practicing "theurgy", white magic, known in Shakespeare's time from neo-Platonic writers, and contrasted with "goety", black magic.[56] Contemporary Dr John Dee regarded himself as practicing this white magic, but all magic was condemned by the church and the state: King James in his book Daemonologie having declared it punishable by death.[57] Early modern plays about magic had portrayed it negatively: most famously in Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, but also, quite recently at the time The Tempest was written, in Jonson's satire The Alchemist, played by Shakespeare's own company, The King's Men, in which the central magician character, Subtle, is merely a con man.[58]

In another more positive interpretation, Prospero's magic is an extension of science. Francis Bacon (who was at the time King James's Attorney-General) had written in his Magnalia Naturae of the possibility of the new philosophy giving humans powers over storms, seasons, germination and harvests.[59]

Prospero often invokes the language of alchemy but his project is to transform not metals, but people: especially Caliban and Prospero's former enemies Antonio, Sebastian and Alsonso.[60] And he has the signifiers that Elizabethan audiences would have associated with magical power: his books, his staff and his robe.[61]

In the end Prospero must abandon his magic. He must free himself from the temptation to use magic for revenge, and from the distraction from his ducal duties which had caused his fall from power twelve years earlier.[62][63]

Prospero and Sycorax

Related to Prospero's magic is the contrast between himself and the unseen character Sycorax, Caliban's mother, an Algerian witch who inhabited the island and died prior to Prospero and Miranda's arrival. Prospero himself makes much of the distinction between his own magical skill and that of Sycorax - both in moral terms (his white magic against her black magic) and in terms of his greater powers - exemplified by the fact that Sycorax "could not again undo"[64] Ariel's imprisonment in a cloven pine and "It was mine [Prospero's] art ... that made gape the pine and let thee out."[65][62]

Scholar Stephen Orgel concludes that "attitudes towards magic in the play ... range from the most positive to the most negative"[63] but that twentieth century criticism emphasised the virtuous aspects of Propspero's magic: citing Frances Yates and Frank Kermode among those who praise Propsero's theurgy over the goety of Sycorax.[63] But Orgel goes on to reject this view as an oversimplification: pointing out that there is no evidence that the spirits controlled by Sycorax are any lower than (or, indeed, any other than) those controlled by Prospero, and also that Ariel is the unwilling servant of both.[66]

The moral superiority of Prospero over Sycorax is also undermined in Prospero's speech renouncing his magic[67] which many in Shakespeare's audiences would have known (see "Sources" above) was a quotation from the witch Medea in Ovid's Metamorphoses.[62][68]

Prospero as Shakespeare

Thomas Campbell in 1838 was the first to consider that Prospero was meant to partially represent Shakespeare, but then abandoned that idea when he came to believe that The Tempest was an early play.[69] Even so, the idea has persisted in the critical canon that Prospero may be partly autobiographical.[69][70]

As it was probably Shakespeare's last solo play, The Tempest has often been seen as a valedictory for his career, especially in the passages beginning "Our revels now are ended..."[71] and "Ye elves of hills...".[72][73] Of the latter, Shakespeare's biographer Samuel Schoenbaum has suggested that it is more pertinent to Shakespeare than to Prospero, since there is nothing to suggested that at Prospero's command "Graves ... have wak'd their sleepers, ope'd, and let 'em forth"[74] - something Shakespeare has done, metaphorically, for many an historical character through his works.[75]

And in the epilogue of the play, Prospero enters into a parabasis (a direct address to the audience) in which he tells the audience "Let your indulgence set me free".[76] Because Prospero is often identified with Shakespeare himself in this final speech, both appear (in the words of Germaine Greer) to be "[not] so much bidding farewell to the stage as begging to be released from it".[77][78][79]

Criticism and interpretation

Summarize

Perspective

Genre

Comedy: The Tempest is listed first among the "Comedies" in the 1623 First Folio of Shakespeare's works.[80] The plot contains elements deriving from the Italian tradition of commedia dell'arte.[81] In Shakespeare's time, whether a work was classified as comedy was chiefly defined by the resolution of its plot: typically one ending in marriage.[82]

Tragicomedy: Although the plot contains similarities to Shakespeare's early comedies, its darker tone has led some twentieth-century critics including Joan Hartwig to label it a tragicomedy in the same tradition as contemporary mixed-mode plays such as the collaborations between Beaumont and Fletcher.[83] E. M. W. Tillyard argued that the classic principles of tragedy were divided between two of Shakespeare's late plays: destruction being explored more fully in The Winter's Tale, and regeneration more fully in The Tempest.[84]

Romance: Four of Shakespeare's late plays - Pericles, Cymbeline, The Winter's Tale and The Tempest - have become grouped together as his romances.[85][86] This places them in a tradition derived from third-century Greek narratives, and practiced by Elizabethan writers including Lyly, Lodge, Greene and Sidney.[85] These plays (in the words of Reginald Foakes) "create a world dominated by chance ... in which we are attuned to delight in and wonder at the unexpected."[87]

The Classical Unities

Like The Comedy of Errors, The Tempest roughly adheres to the unities of time, place, and action.[88] Shakespeare's other plays rarely respected the three unities, taking place in separate locations miles apart and over several days or even years.[89] Of Shakespeare's other late romances, for example, The Winter's Tale contains a gap of sixteen years, and Cymbeline's action veers between Britain and Italy.[90] In contrast, The Tempest's events unfold in real time before the audience, taking around three hours.[91][92][90] All action is unified into one basic plot: Prospero's struggle to regain his dukedom; it is also confined to one place, a fictional island.

Location of Prospero's Island

The action takes place on an enchanted island ruled by Prospero, which must be located in the Mediterranean Sea, since it is encountered by travelers attempting to sail from Tunis to Naples.[93][94] However it is often thought of in subsequent criticism as being in the North Atlantic: partly because of the play's association with the wreck of the Sea Venture (see "Sources" above) and Ariel's suggestion of its proximity to the "still-vexed Bermoothes"[95] both of which relate it to Bermuda, but also because of the colonial context of the play - and the way in which it subsequently came to be viewed by postcolonial critics - which suggest a setting in the New World.[96][97] Also indicative of a New World setting are the name of Sycorax's god, Setebos, which derives from South America, and the source of Gonzalo's Utopia in Montaigne's essay Of The Cannibals (see also "Sources" above).[98]

Prospero as Hero

Throughout the critical history of the play until the mid-twentieth century, Prospero was generally regarded as an admirable figure: "prickly but essentially lovable" (in the words of Martin Butler).[99] But in more recent criticism and performance he has come to be seen as self-doubting and controlling and his attitude one of (in Martin Butler's words again) "suspicion, strain and paranoia".[100]

This shift in the attitude of critics is partly due to the absence of soliloquies in which Prospero can make his feelings known to the audience. Did he always intend to forgive his enemies, for example, or is his statement that "the rarer action is in virtue than in vengeance"[101] a conclusion he reaches during the currency of the play?[102] But it also reflects changing moral and political assumptions about the nature of rule, and of family.[102]

Postcolonial

The Tempest is one of the plays (alongside The Merchant of Venice and Othello) most analysed in a Postcolonial context,[103] and indeed is considered to be the work upon which postcolonial studies first took root.[104] The play has become, in the words of Peter Hulme, "emblematic of the founding years of England's colonialism".[105] From a postcolonial perspective, Prospero is seen as having imported to the island the social and moral structures of Milan (meaning, for early audiences, of London) by seizing rule, and making slaves of its inhabitants Caliban and Ariel.[106]

Traditionally, it was common to view The Tempest as an allegory of artistic creativity, with Prospero as all-knowing and benevolent.[107] Beginning in about 1950, with the publication of Psychology of Colonization by Octave Mannoni, postcolonial theorists have increasingly appropriated The Tempest and reinterpreted it in light of postcolonial theory. This new way of looking at the text explored the effect of the "coloniser" (Prospero) on the "colonised" (Ariel and Caliban). Although Ariel is often overlooked in these debates in favour of the more intriguing Caliban, he is nonetheless an essential component of them.[108] So, in the 1960s and 1970s, Caliban's "This island's mine... which thou tak'st from me"[109] became a rallying-cry for African and Caribbean intellectuals.[107]

But critics such as Meredith Anne Skura have pointed out the limits of the postcolonial approach, referencing its projection backwards onto a play from the 1610s of historical events which happened later, and stressing the point that, in the story, Prospero does not choose to colonise the island, but runs aground there after being set adrift.[110]

Feminist

Feminist interpretations of The Tempest consider the play in terms of gender roles and relationships among the characters on stage, and consider how concepts of gender are constructed and presented by the text, and explore the supporting consciousnesses and ideologies, all with an awareness of imbalances and injustices.[111] Two early feminist interpretations of The Tempest are included in Anna Jameson's Shakespeare's Heroines (1832) and Mary Clarke's The Girlhood of Shakespeare's Heroines (1851).[112][113]

The Tempest is a play created in a male dominated culture and society, a gender imbalance the play explores metaphorically by having only one major female role, Miranda. Miranda is fifteen, intelligent, naive, and beautiful. The only humans she has ever encountered in her life are male. Prospero sees himself as her primary teacher, and asks if she can remember a time before they arrived to the island—he assumes that she cannot. When Miranda has a memory of "four or five women" tending to her younger self (1.2.44–47), it disturbs Prospero, who prefers to portray himself as her only teacher, and the absolute source of her own history—anything before his teachings in Miranda's mind should be a dark "abysm", according to him. (1.2.48–50) The "four or five women" Miranda remembers may symbolize the young girl's desire for something other than only men.[9][114]

Other women, such as Caliban's mother Sycorax, Miranda's mother and Alonso's daughter Claribel, are only mentioned. Because of the small role women play in the story in comparison to other Shakespeare plays, The Tempest has attracted much feminist criticism. Miranda is typically viewed as being completely deprived of freedom by her father. Her only duty in his eyes is to remain chaste. Ann Thompson argues that Miranda, in a manner typical of women in a colonial atmosphere, has completely internalised the patriarchal order of things, thinking of herself as subordinate to her father.[115]

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Performance history

Shakespeare's day

A record exists of a performance of The Tempest on 1 November 1611 by the King's Men before James I and the English royal court at Whitehall Palace on Hallowmas night.[116] The play was one of the six Shakespeare plays (and eight others for a total of 14) acted at court during the winter of 1612–13 as part of the festivities surrounding the marriage of Princess Elizabeth with Frederick V, the Elector of the Palatinate of the Rhine.[117] There is no further public performance recorded prior to the Restoration; but in his 1669 preface to the Dryden/Davenant version, John Dryden states that The Tempest had been performed at the Blackfriars Theatre.[118] Careful consideration of stage directions within the play supports this, strongly suggesting that the play was written with Blackfriars Theatre rather than the Globe Theatre in mind.[119][120] But the mid-20th century critic Frank Kermode, while agreeing that The Tempest is a Blackfriars play, argued that it could easily have been accommodated at The Globe also, as others of Shakespeare's late romances were.[121]

Restoration and 18th century

Adaptations of the play, not Shakespeare's original, dominated the performance history of The Tempest from the English Restoration until the mid-19th century.[122] Upon the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Sir William Davenant's Duke's Company had the rights to perform The Tempest.[123] In 1667 Davenant and John Dryden made heavy cuts and adapted it as The Tempest, or The Enchanted Island. They tried to appeal to upper-class audiences by emphasising royalist political and social ideals: monarchy is the natural form of government; patriarchal authority decisive in education and marriage; and patrilineality preeminent in inheritance and ownership of property.[122] They also added characters and plotlines: Miranda has a sister, named Dorinda; Caliban also has a sister, named Sycorax. As a parallel to Shakespeare's Miranda/Ferdinand plot, Prospero has a foster-son, Hippolito, who has never set eyes on a woman.[124] Hippolito was a popular breeches role, a man played by a woman, popular with Restoration theatre management for the opportunity to reveal actresses' legs.[125] Scholar Michael Dobson has described The Tempest, or The Enchanted Island by Dryden and Davenant as "the most frequently revived play of the entire Restoration" and as establishing the importance of enhanced and additional roles for women.[126]

In 1674, Thomas Shadwell re-adapted Dryden and Davenant as an "opera" of the same name - meaning a play with sections that were to be sung or danced. Restoration playgoers appear to have regarded the Dryden/Davenant/Shadwell version as Shakespeare's: Samuel Pepys, for example, described it as "an old play of Shakespeares" in his diary. The opera was extremely popular, and "full of so good variety, that I cannot be more pleased almost in a comedy" according to Pepys.[127] Prospero in this version is very different from Shakespeare's: Eckhard Auberlen describes him as "reduced to the status of a Polonius-like overbusy father, intent on protecting the chastity of his two sexually naive daughters while planning advantageous dynastic marriages for them".[128] The operatic Enchanted Island was successful enough to provoke a parody, The Mock Tempest, or The Enchanted Castle, written by Thomas Duffett for the King's Company in 1675. It opened with what appeared to be a tempest, but turned out to be a riot in a brothel.[129]

The Tempest was one of the staples of the repertoire of Romantic Era theatres. John Philip Kemble produced an acting version which was closer to Shakespeare's original, but nevertheless retained Dorinda and Hippolito.[130] Kemble was much-mocked for his insistence on archaic pronunciation of Shakespeare's texts, including "aitches" for "aches". It was said that spectators "packed the pit, just to enjoy hissing Kemble's delivery of 'I'll rack thee with old cramps, / Fill all they bones with aches'."[131][132]

19th century

It was not until William Charles Macready's influential production in 1838 that Shakespeare's text established its primacy over the adapted and operatic versions which had been popular for most of the previous two centuries. The performance was particularly admired for George Bennett's performance as Caliban; it was described by Patrick MacDonnell—in his "An Essay on the Play of The Tempest" published in 1840—as "maintaining in his mind, a strong resistance to that tyranny, which held him in the thraldom of slavery".[133]

The Victorian era marked the height of the movement which would later be described as "pictorial": based on lavish sets and visual spectacle, heavily cut texts making room for lengthy scene-changes, and elaborate stage effects.[134] In Charles Kean's 1857 production of The Tempest, Ariel was several times seen to descend in a ball of fire.[135] The hundred and forty stagehands supposedly employed on this production were described by The Literary Gazette as "unseen ... but alas never unheard". Hans Christian Andersen also saw this production and described Ariel as "isolated by the electric ray", referring to the effect of a carbon arc lamp directed at the actress playing the role.[136]

In these Victorian productions it was widely accepted that the spectacle of the opening sea-storm was the highlight of the show, with the custom developing of dropping Shakespeare's lines from the opening scene altogether.[137] The next generation of producers, which included William Poel and Harley Granville-Barker, returned to a leaner and more text-based style.[138]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Caliban, not Prospero, was perceived as the star act of The Tempest, and was the role which the actor-managers chose for themselves. Frank Benson researched the role by viewing monkeys and baboons at the zoo. On stage, described by one reviewer as "half-monkey, half-coconut", he hung upside-down from a tree and gibbered.[139][140]

20th century

Continuing the late-19th-century tradition, in 1904 Herbert Beerbohm Tree wore fur and seaweed to play Caliban, with waist-length hair and apelike bearing, suggestive of a primitive part-animal part-human stage of evolution.[139] This "missing link" portrayal of Caliban became the norm in productions until Roger Livesey, in 1934, was the first actor to play the role with black makeup. In 1945 Canada Lee played the role at the Theatre Guild in New York, establishing a tradition of black actors taking the role, including Earle Hyman in 1960 and James Earl Jones in 1962.[141]

In 1916, Percy MacKaye presented a community masque, Caliban by the Yellow Sands, at the Lewisohn Stadium in New York. Amidst a huge cast of dancers and masquers, the pageant centres on the rebellious nature of Caliban but ends with his plea for more knowledge ("I yearn to build, to be thine Artist / And 'stablish this thine Earth among the stars- / Beautiful!") followed by Shakespeare, as a character, reciting Prospero's "Our revels now are ended" speech.[142][143]

John Gielgud played Prospero numerous times, and is, according to Douglas Brode, "universally heralded as ... [the 20th] century's greatest stage Prospero".[144] Scholar Martin Butler has described his Propspero as "a vigorous, forceful and intellectually alert individual, he always dominated the play, but was not easily likeable."[145]

In spite of the existing tradition of a black actor playing Caliban opposite a white Prospero, postcolonial interpretations of the play did not find their way onto the stage until the 1970s.[146] Performances in England directed by Jonathan Miller and by Clifford Williams explicitly portrayed Prospero as coloniser. [147][148] And later, in 1993, Sam Mendes directed a 1993 RSC production in which Simon Russell Beale's Ariel was openly resentful of the control exercised by Alec McCowen's Prospero. Controversially, in the early performances of the run, Ariel spat at Prospero, once granted his freedom.[149][150] [151]

Psychoanalytic interpretations have proved more difficult to depict on stage.[148] Gerald Freedman's production at the American Shakespeare Theatre in 1979 and Ron Daniels' Royal Shakespeare Company production in 1982 both attempted to depict Ariel and Caliban as opposing aspects of Prospero's psyche, but neither was regarded as wholly successful.[152][153] Productions in the late 20th-century have gradually increased the focus placed on sexual tensions between the characters, including Prospero/Miranda, Prospero/Ariel, Miranda/Caliban, Miranda/Ferdinand and Caliban/Trinculo.[154]

Italian director Giorgio Strehler directed a Brecht-inspired version of the Tempest from 1978 which proved influential in containing the much-copied image of Prospero at the centre of the play's opening storm scene, orchestrating the visual effects around him.[155]

Japanese theatre styles have been applied to The Tempest. In 1988 and again in 1992 Yukio Ninagawa brought his version of The Tempest to the UK. It was staged as a rehearsal of a Noh drama, with a traditional Noh theatre at the back of the stage, but also using elements which were at odds with Noh conventions.[156][157] In 1992, Minoru Fujita presented a Bunraku (Japanese puppet) version in Osaka and at the Tokyo Globe.[158]

21st Century

The Tempest was performed at the Globe Theatre in 2000 with Vanessa Redgrave as Prospero, playing the role as neither male nor female, but with "authority, humanity and humour ... a watchful parent to both Miranda and Ariel".[159] While the audience respected Prospero, Jasper Britton's Caliban "was their man" (in Peter Thomson's words), in spite of the fact that he spat fish at the groundlings, and singled some of them out for humiliating encounters.[160]

By the end of 2005, BBC Radio had aired 21 productions of The Tempest, more than any other play by Shakespeare.[161]

In 2016 The Tempest was produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company. Directed by Gregory Doran, and featuring Simon Russell Beale as Prospero, the RSC's version used motion capture to project Ariel in real time as a "pixelated humanoid sprite" on stage. The performance was in collaboration with The Imaginarium and Intel, and featured (in the words of the London Standard's review) "some ... gorgeous, some interesting, and some gimmicky and distracting"[162] use of light, special effects, and set design.[162][163]

In 2019, Mohegan writer Madeline Sayet's solo show Where We Belong at Shakespeare's Globe engaged in a postcolonial speculation about the European characters' abandonment of the island ad the play's end: wondering whether Caliban's native language would return to him.[164]

Music

The Tempest has more music than any other Shakespeare play, and has proved more popular as a subject for composers than most of Shakespeare's plays. Scholar Julie Sanders ascribes this to the "perceived 'musicality' or lyricism" of the play.[165]

Two settings of songs from The Tempest which may have been used in performances during Shakespeare's lifetime have survived. These are "Full Fathom Five" and "Where The Bee Sucks There Suck I" in the 1659 publication Cheerful Ayres or Ballads, in which they are attributed to Robert Johnson, who regularly composed for the King's Men.[166] It has been common throughout the history of the play for the producers to commission contemporary settings of these two songs, and also of "Come Unto These Yellow Sands".[167]

Among those who wrote incidental music to The Tempest are:

- Arthur Sullivan: his graduation piece, completed in 1861, was a set of incidental music to "The Tempest".[168] His score was still in use half a century later to add atmosphere the Old Vic's 1914 production.[169]

- Ernest Chausson: in 1888 he wrote incidental music for La tempête, a French translation by Maurice Bouchor. This is believed to be the first orchestral work that made use of the celesta.[170][171]

- Jean Sibelius: his 1926 incidental music was written for a lavish production at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen. An epilogue was added for a 1927 performance in Helsinki.[172] He represented individual characters through instrumentation choices: particularly admired was his use of harps and percussion to represent Prospero, said to capture the "resonant ambiguity of the character".[173]

Ballet sequences have been used in many performances of the play since Restoration times.[174]

At least forty-six operas or semi-operas based on The Tempest exist.[175] Michael Tippett's 1971 opera The Knot Garden contains various allusions to The Tempest. In Act 3, a psychoanalyst, Mangus, pretends to be Prospero and uses situations from Shakespeare's play in his therapy sessions.[176] Michael Nyman's 1991 opera Noises, Sounds & Sweet Airs was first performed as an opera-ballet choreographed by Karine Saporta. The three vocalists, a soprano, contralto, and tenor, are voices rather than individual characters, with the tenor just as likely as the soprano to sing Miranda, or all three sing as one character.[177][178]

The soprano who sings the part of Ariel in Thomas Adès's 2004 opera The Tempest is stretched at the higher end of the register, highlighting the androgyny of the role.[179][180][181] Luca Lombardi's Prospero was premiered in April 2006 at Nuremberg Opera House. Ariel is sung by 4 female voices (S,S,MS,A) and has an instrumental alter ego on stage (flute). There is an instrumental alter ego (cello) also for Prospero.[182][183]

Stage musicals derived from The Tempest have been produced. A production called The Tempest: A Musical was produced at the Cherry Lane Theatre in New York City in December 2006, with a concept credited to Thomas Meehan and a script by Daniel Neiden (who also wrote the songs) and Ryan Knowles.[184] Neiden had previously been connected with another musical, entitled Tempest Toss'd.[185] In September 2013, The Public Theater produced a new large-scale stage musical at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park, directed by Lear deBessonet with a cast of more than 200.[186][187]

The Tempest has also influenced songs written in the folk and hippie traditions: for example, versions of "Full Fathom Five" were recorded by Marianne Faithfull for Come My Way in 1965 and by Pete Seeger for Dangerous Songs!? in 1966.[188]

Literature

Percy Bysshe Shelley was one of the earliest poets to be influenced by The Tempest. His "With a Guitar, To Jane" identifies Ariel with the poet and his songs with poetry. The poem uses simple diction to convey Ariel's closeness to nature and "imitates the straightforward beauty of Shakespeare's original songs".[189] Following the publication of Darwin's ideas on evolution, writers began to question mankind's place in the world and its relationship with God. One writer who explored these ideas was Robert Browning, whose poem "Caliban upon Setebos" (1864) sets Shakespeare's character pondering theological and philosophical questions.[190] The French philosopher Ernest Renan wrote a closet drama, Caliban: Suite de La Tempête (Caliban: Sequel to The Tempest), in 1878. This features a female Ariel who follows Prospero back to Milan, and a Caliban who leads a coup against Prospero, after the success of which he actively imitates his former master's virtues.[191] W. H. Auden's long poem The Sea and the Mirror is in three parts, Prospero's farewell to Ariel referring to the matters unresolved at the end of the play; a reflection by each of the supporting characters on their experiences and intentions; then a prose narrative "Caliban to the Audience" which takes a Freudian viewpoint, seeing Caliban as Prospero's libidinous secret self.[192][193]

The book Brave New World by Aldous Huxley references The Tempest in the title, and explores genetically modified citizens and the subsequent social effects. The novel and the phrase from The Tempest, Barclay"brave new world",[194] have since been associated with public debate about humankind's understanding and use of genetic modification, in particular with regards to humans.[195]

Postcolonial ideas influenced late 20th-century writings. Aimé Césaire of Martinique, in his 1969 French-language play Une Tempête sets The Tempest in a colony suffering unrest, and prefuiguring black independence. The play portrays Ariel as a mulatto who, unlike the more rebellious black Caliban, feels that negotiation and partnership is the way to freedom from the colonisers.[196][197] Roberto Fernandez Retamar sets his version of the play in Cuba, and portrays Ariel as a wealthy Cuban (in comparison to the lower-class Caliban) who also must choose between rebellion or negotiation.[198][199] Barbadian poet E. P. Kamau Brathwaite in his 1969 poem "Caliban" identifies the character with the history of colonialism, between the first voyage of Columbus through to the Cuban Revolution.[200] Jamaican-American author Michelle Cliff's No Telephone to Heaven has a protagonist who identifies with both Caliban and Miranda.[201] And the figure of Caliban influenced numerous works of African literature in the 1970s, including Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o of Kenya's A Grain of Wheat, and David Wallace of Zambia's Do You Love Me, Master?[202][203] In 1995, Sierra Leonean Lemuel Johnson's Highlife for Caliban imagined Caliban as king of his own kingdom.[204]

A similar phenomenon occurred in relation to feminist ideas in late 20th-century Canada, where several writers produced works inspired by Miranda, including The Diviners by Margaret Laurence, Prospero's Daughter by Constance Beresford-Howe and The Measure of Miranda by Sarah Murphy.[205] Other writers have feminised Ariel (as in Marina Warner's novel Indigo) or Caliban (as in Suniti Namjoshi's sequence of poems Snapshots of Caliban).[206]

Art

From the mid-18th century, Shakespeare's plays, including The Tempest, began to appear as the subject of paintings.[207] In around 1735, William Hogarth produced his painting A Scene from The Tempest: "a baroque, sentimental fantasy costumed in the style of Van Dyck and Rembrandt".[207] The painting is based upon Shakespeare's text, containing no representation of the stage, nor of the (Davenant-Dryden centred) stage tradition of the time.[208] Henry Fuseli, in a painting commissioned for the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery (1789) modelled his Prospero on Leonardo da Vinci.[209][210] These two 18th-century depictions of the play indicate that Prospero was regarded as its moral centre: viewers of Hogarth's and Fuseli's paintings would have accepted Prospero's wisdom and authority.[211] John Everett Millais's Ferdinand Lured by Ariel (1851) is among the Pre-Raphaelite paintings based on the play. In the late 19th century, artists tended to depict Caliban as a Darwinian "missing-link", with fish-like or ape-like features, as evidenced in Joseph Noel Paton's Caliban, and discussed in Daniel Wilson's book Caliban: The Missing Link (1873).[212][191][213]

Charles Knight produced the Pictorial Edition of the Works of Shakespeare in eight volumes (1838–43). The work attempted to translate the contents of the plays into pictorial form. This extended not just to the action, but also to images and metaphors: Gonzalo's line about "mountaineers dewlapped like bulls" is illustrated with a picture of a Swiss peasant with a goitre.[214] In 1908, Edmund Dulac produced an edition of Shakespeare's Comedy of The Tempest with a scholarly plot summary and commentary by Arthur Quiller-Couch, lavishly bound and illustrated with 40 watercolour illustrations. The illustrations highlight the fairy-tale quality of the play, avoiding its dark side. Of the 40, only 12 are direct depictions of the action of the play: the others are based on action before the play begins, or on images such as "full fathom five thy father lies" or "sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not".[215]

In 2015 Charmaine Lurch's installation Revisiting Sycorax gave a physical form to a figure only spoken about in Shakespeare's play, and intended to draw attention to the discrepancy between the presence of African women in the world and the way they are spoken of in European male dialogue.[216]

Screen

The Tempest first appeared on the screen in 1905. Charles Urban filmed the opening storm sequence of Herbert Beerbohm Tree's version at Her Majesty's Theatre for a 2+1⁄2-minute flicker, whose individual frames were hand-tinted, long before the invention of colour film. In 1908 Percy Stow directed The Tempest running a little over ten minutes, which is now a part of the British Film Institute's compilation Silent Shakespeare. It portrays a condensed version of Shakespeare's play in a series of short scenes linked by intertitles. At least two other silent versions, one from 1911 by Edwin Thanhouser, are known to have existed, but have been lost.[217]

The plot was adapted for the Western Yellow Sky, directed by William A. Wellman, in 1946.[218] The 1956 science fiction film Forbidden Planet set the story on a planet in space, Altair IV, instead of an island. Professor Morbius (Walter Pidgeon) and his daughter Altaira (Anne Francis) are the Prospero and Miranda figures, whose lives are disrupted by the arrival of a spaceship from Earth. Ariel is represented by the helpful Robby the Robot. Caliban is represented by the dangerous and invisible "monster from the id", a technologically-enhanced projection of Morbius' psyche.[219]

Writing in 2000, Douglas Brode expressed the opinion that there had only been one screen "performance" of The Tempest since the silent era: he describes all other versions as "variations". That one performance is the Hallmark Hall of Fame version from 1960, directed by George Schaefer, and starring Maurice Evans as Prospero, Richard Burton as Caliban, Lee Remick as Miranda, and Roddy McDowall as Ariel. It cut the play to slightly less than ninety minutes. Critic Virginia Vaughan praised it as "light as a soufflé, but ... substantial enough for the main course".[217]

In 1979, Derek Jarman produced the homoerotic film The Tempest that used Shakespeare's language, but was most notable for its deviations from Shakespeare. One scene shows a corpulent and naked Sycorax (Claire Davenport) breastfeeding her adult son Caliban (Jack Birkett). The film reaches its climax with Elisabeth Welch belting out "Stormy Weather".[220][221] The central performances were Toyah Willcox's Miranda and Heathcote Williams's Prospero, a "dark brooding figure who takes pleasure in exploiting both his servants".[222]

Paul Mazursky's 1982 modern-language adaptation Tempest, with Philip Dimitrius (the Prospero character, played by John Cassavetes) as a disillusioned New York architect who retreats to a lonely Greek island with his daughter Miranda after learning of his wife Antonia's infidelity with Alonzo, dealt frankly with the sexual tensions of the characters' isolated existence. The Caliban character, the goatherd Kalibanos, asks Philip which of them is going to have sex with Miranda.[222]

John Gielgud wrote that playing Prospero in a film of The Tempest was his life's ambition. Eventually, the project was taken on by Peter Greenaway, who directed Prospero's Books (1991) featuring "an 87-year-old John Gielgud and an impressive amount of nudity".[223] Prospero is reimagined as the author of The Tempest, speaking the lines of the other characters, as well as his own.[144] Although the film was acknowledged as innovative for its "unprecedented visual complexity",[224] critical responses were frequently negative: John Simon called it "contemptible and pretentious".[225][226]

Closer to the spirit of Shakespeare's original, in the view of critics such as Brode, is Leon Garfield's abridgement of the play for S4C's 1992 Shakespeare: The Animated Tales series. The 29-minute production, directed by Stanislav Sokolov and featuring Timothy West as the voice of Prospero, used stop-motion puppets to capture the fairy-tale quality of the play.[227] Another "offbeat variation" (in Brode's words) was produced for NBC in 1998: Jack Bender's The Tempest featured Peter Fonda as Gideon Prosper, a Southern slave-owner forced off his plantation by his brother shortly before the Civil War. A magician who has learned his art from one of his slaves, Prosper uses his magic to protect his teenage daughter and to assist the Union Army.[228]

Director Julie Taymor's 2010 adaptation The Tempest starred Helen Mirren as Prospera, a female Prospero character: with the text adapted to establish a different backstory between Prospera and Antonio. The film was praised for its powerful visual imagery used in place of Shakespearean language.[229]

Citations

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.