The Kekulé Problem

2017 essay by Cormac McCarthy From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

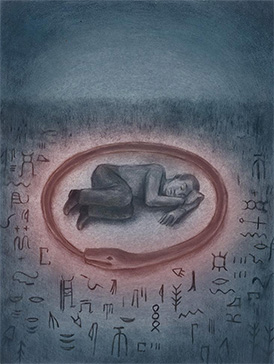

"The Kekulé Problem" is a 2017 essay written by the American author Cormac McCarthy for the Santa Fe Institute (SFI). It was McCarthy's first published work of non-fiction. The science magazine Nautilus first ran the article online on April 20, 2017, then printed it as the cover story for an issue on the subject of consciousness. David Krakauer, an American evolutionary biologist who had known McCarthy for two decades, wrote a brief introduction. Don Kilpatrick III provided illustrations.

Illustration by Don Kilpatrick III | |

| Author | Cormac McCarthy |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre |

|

| Published in | Nautilus 47 |

Publication date | April 20, 2017 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | |

Summary

Kekulé

Kekulé's dream

The title refers to the chemist August Kekulé's realization of the ringed structure of benzene after a symbolic dream of the ouroboros. McCarthy asks how the non-linguistic unconscious mind could provide a meaningful solution to a fundamentally linguistic problem.

McCarthy analyzes a famous dream of August Kekulé's as a model of the unconscious mind and the origins of language. He theorizes about the nature of the unconscious mind and its separation from human language. The unconscious, according to McCarthy, "is a machine for operating an animal" and that "all animals have an unconscious." McCarthy postulates that while the unconscious mind is thus a biologically determined phenomenon, language is not.

Analysis

"The Kekulé Problem" is written in the style of a reflective philosophical essay in McCarthy's own first-person voice. There are flashes of direct autobiography, such as an anecdote stemming from one of McCarthy's frequent lunchtime conversations with his friend, the physicist George Zweig. Such elements of memoir are virtually absent from any of McCarthy's published writings.[1] Peter Josyph called it "a reader's memoir. If you like, a thinker's memoir. A wonderer's memoir. Notes of a mental traveler. McCarthy Table Talk," placing it in the tradition of such essayists as "Seneca, Montaigne, Thoreau, Twain, Whitman, Huxley, Orwell, Cendrars, Saroyan, Woolf, Eisely [sic], Vidal, Miller, Kerouac, Selzer."[2]

Publication

"The Kekulé Problem" was published in the science magazine Nautilus on April 20, 2017.[3] The essay is about 3,000 words long.[4]

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

In a review for The New Yorker, Nick Romeo said the essay was a successful adaptation of McCarthy's distinctive writing style into the realm of non-fiction, with its "folksy locutions and no-nonsense sentence fragments and even, at points, the vaguely biblical grandiloquence of his earlier novels", and remarked that the author's "thoughts on the unconscious", though "framed as scientific reflections ... also creep toward theology."[4] At Quartz, Lila MacLellan said the essay provided rare insight into McCarthy's thinking during his time at SFI and praised the way it "somehow distilled the lofty ideas, unanswered questions, and epiphanies collected during this long inquiry into a beautifully written narrative."[5] Steven Pinker, a Canadian-American psycholinguist and author, said he agreed with McCarthy's overall notion that "thought is not the same thing as language" but warned against drawing too many conclusions from the example of Kekulé's dream, noting that "[t]he vast majority of dreams and reveries don't solve major problems in the history of science."[4]

John Gray—a British philosopher and book critic for the New Statesman—said the subject of the Kekulé problem was "hardly surprising" for McCarthy, describing the author's decades-long career in fiction as an "unrelenting struggle to say the unsayable."[6] The McCarthy scholar Jay Ellis said that the paper's greatest value was the insight it provided into the author's worldview, and highlighted its latent dramatic qualities:

[T]he unconscious appears like a Beckett character, difficult to talk with, yet impossible to leave alone. ... The best example of McCarthy inferring intention from the unconscious comes in one of his many strings of rhetorical questions: "It's hard to escape the conclusion that the unconscious is laboring under a moral compulsion to educate us. (Moral compulsion? Is he serious?)" The logic here leaps with dramatic humor.[7]

References

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.