Charge of the Light Brigade

1854 Crimean War cavalry charge From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Charge of the Light Brigade was a military action undertaken by British light cavalry against Russian forces during the Battle of Balaclava in the Crimean War, resulting in many casualties to the cavalry. On 25 October 1854, the Light Brigade, led by Lord Cardigan, mounted a frontal assault against a Russian artillery battery which was well-prepared with excellent fields of defensive fire. The charge was the result of a misunderstood order from the commander-in-chief, Lord Raglan, who had intended the Light Brigade to attack a different objective for which light cavalry was better suited, to prevent the Russians from removing captured guns from overrun Turkish positions. The Light Brigade made its charge under withering direct fire and reached its target, scattering some of the gunners, but was forced to retreat immediately.

| Charge of the Light Brigade | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Battle of Balaclava, Crimean War | |||||||

The Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava by William Simpson (1855), illustrating the Light Brigade's charge into the "Valley of Death" from the Russian perspective. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

United Kingdom France | Russia | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

James Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan Armand-Octave-Marie d'Allonville | Pavel Liprandi | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| About 670 (Adkin: 668; Brighton: "at least" 666) | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

~110 killed ~161 wounded | Unknown | ||||||

The events were the subject of Alfred, Lord Tennyson's narrative poem "The Charge of the Light Brigade" (1854), published six weeks after the event. Its lines emphasise the valour of the cavalry in carrying out their orders regardless of the risk. Responsibility for the miscommunication is disputed, as the order was vague and Captain Louis Nolan, who delivered the written orders with some oral interpretation, was killed in the first minute of the assault.

Background

Summarize

Perspective

The charge was made by the Light Brigade of the British cavalry, which consisted of the 4th and 13th Light Dragoons, the 17th Lancers, and the 8th and 11th Hussars,[1] under the command of Major General James Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan. Also present that day was the Heavy Brigade, commanded by Major General James Yorke Scarlett, who was a past Commanding Officer of the 5th Dragoon Guards. The Heavy Brigade was made up of the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards, the 5th Dragoon Guards, the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons and the Scots Greys. The two brigades were the only British cavalry force at the battle.[2]

The Light Brigade was the British light cavalry force. It rode unarmoured light fast horses. The men were armed with lances and sabres. Optimized for maximum mobility and speed, they were intended for reconnaissance and skirmishing. They were also ideal for cutting down infantry and artillery units as they tried to retreat.[3]

The Heavy Brigade under James Scarlett was the British heavy cavalry force. It rode large, heavy chargers. The men were equipped with metal helmets and armed with cavalry swords for close combat. They were intended as the primary British shock force, leading frontal charges to break enemy lines.[3]

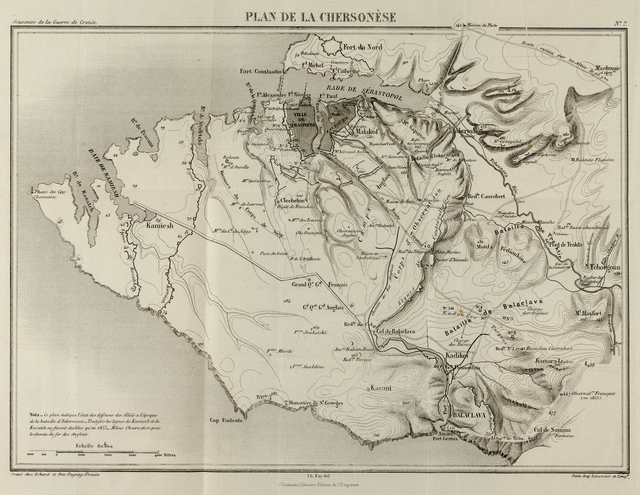

Overall command of the British cavalry resided with Lieutenant General George Bingham, 3rd Earl of Lucan. Cardigan and Lucan were brothers-in-law who disliked each other intensely. Lucan received an order from the army commander Lord Raglan stating: "Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front, follow the enemy, and try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns. Troop horse artillery may accompany. French cavalry is on your left. Immediate".[4] Raglan wanted the light cavalry to prevent the Russians from successfully withdrawing the naval guns from the redoubts they had captured on the reverse side of the Causeway Heights, the hill forming the south side of the valley. This was an optimal task for the Light Brigade, as their superior speed would ensure the Russians would be forced to either quickly abandon the cumbersome guns or be cut down en masse while they tried to flee with them.

Raglan could see what was happening from his high vantage point on the west side of the valley. However, the lie of the land around the cavalry position stopped Lucan from seeing the Russians' efforts to remove the guns from the redoubts.[5]

The order was drafted by Brigadier Richard Airey and carried by Captain Louis Nolan. Nolan carried the further oral instruction that the cavalry was to attack immediately.[1] By Lucan's account, when he asked Nolan what guns were referred to Nolan indicated in a most disrespectful way (with a wide sweep of his arm) the mass of Russian guns at the end of the valley: "There, my lord, is your enemy; there are your guns."[6][7] His reasons for the misdirection are unknown because he was killed in the ensuing battle.

In response to the order, Lucan instructed Cardigan to lead his command of about 670 troopers of the Light Brigade straight into the valley between the Fedyukhin Heights and the Causeway Heights. (Russell's report in The Times recorded that just short of 200 men were sick or for other reasons left behind in camp on the day, leaving "607 sabres" to take part in the charge.[1]) In his poem, "The Charge of the Light Brigade" (1854), Tennyson dubbed this hollow "The Valley of Death".

The opposing Russian forces were commanded by Pavel Liprandi. According to an estimate by Nicholas Woods, correspondent of The Morning Post, the forces at his disposal amounted to 25,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry, supported by 30 or 40 cannon.[8] These forces were deployed on both sides and at the opposite end of the valley.

Lucan was to follow with the Heavy Brigade. The Heavy Brigade was intended for frontal assaults on infantry positions, but neither force was anywhere near to being equipped for a frontal assault on a fully dug-in and alerted artillery, much less one with an excellent line of sight over a mile in length and supported on two sides by artillery batteries providing enfilading fire from elevated ground.[1]

The charge

Summarize

Perspective

The Light Brigade set off down the valley with Cardigan in front, leading the charge on his horse Ronald.[10][11] Almost at once, Nolan rushed across the front, passing in front of Cardigan. It may be that he realised that the charge was aimed at the wrong target and was attempting to stop or turn the brigade,[12] but he was killed by an artillery shell and the cavalry continued on its course. Captain Godfrey Morgan was close by:

The first shell burst in the air about 100 yards in front of us. The next one dropped in front of Nolan's horse and exploded on touching the ground. He uttered a wild yell as his horse turned round, and, with his arms extended, the reins dropped on the animal's neck, he trotted towards us, but in a few yards dropped dead off his horse. I do not imagine that anybody except those in the front line of the 17th Lancers saw what had happened.

We went on. When we got about two or three hundred yards the battery of the Russian Horse Artillery opened fire. I do not recollect hearing a word from anybody as we gradually broke from a trot to a canter, though the noise of the striking of men and horses by grape and round shot was deafening, while the dust and gravel struck up by the round shot that fell short was almost blinding, and irritated my horse so that I could scarcely hold him at all. But as we came nearer I could see plainly enough, especially when I was about a hundred yards from the guns. I appeared to be riding straight on to the muzzle of one of the guns, and I distinctly saw the gunner apply his fuse. I shut my eyes then, for I thought that settled the question as far as I was concerned. But the shot just missed me and struck the man on my right full in the chest.

In another minute I was on the gun and the leading Russian's grey horse, shot, I suppose, with a pistol by somebody on my right, fell across my horse, dragging it over with him and pinning me in between the gun and himself. A Russian gunner on foot at once covered me with his carbine. He was just within reach of my sword, and I struck him across his neck. The blow did not do much harm, but it disconcerted his aim. At the same time a mounted gunner struck my horse on the forehead with his sabre. Spurring "Sir Briggs," he half jumped, half blundered, over the fallen horses, and then for a short time bolted with me. I only remember finding myself alone among the Russians trying to get out as best I could. This, by some chance, I did, in spite of the attempts of the Russians to cut me down.[13]

The Light Brigade faced withering fire from three sides which devastated their force on the ride, yet they were able to engage the Russian forces at the end of the valley and force them back from the redoubt. Nonetheless, they had suffered heavy casualties and were soon forced to retire. The surviving Russian artillerymen returned to their guns and opened fire with grapeshot and canister shot, indiscriminately at the mêlée of friend and foe before them.[1] Captain Morgan continues:

When clear again of the guns I saw two or three of my men making their way back, and as the fire from both flanks was still heavy it was a matter of running the gauntlet again. I have not sufficient recollection of minor incidents to describe them, as probably no two men who were in that charge would describe it in the same way. When I was back pretty nearly where we started from I found that I was the senior officer of those not wounded, and, consequently, in command, there being two others, both juniors to me, in the same position — Lieut. Wombwell and Cornet Cleveland.[13]

Lucan and his troops of the Heavy Brigade failed to provide any support for the Light Brigade; they entered the mouth of the valley, but did not advance further. Lucan's explanation was that he saw no point in having a second brigade mown down, and he was best positioned to render assistance to survivors returning from the charge.[14] The French light cavalry, the Chasseurs d'Afrique, was of more assistance, clearing the Fedyukhin Heights of the two half-batteries of guns, two infantry battalions, and Cossacks to ensure that the Light Brigade would not be fired upon from that flank, and it provided cover for the remaining elements of the Light Brigade as they withdrew.[1][15]

War correspondent William Howard Russell witnessed the battle and declared, "Our Light Brigade was annihilated by their own rashness, and by the brutality of a ferocious enemy." His account of the casualties (along with non-contemporary percentages calculated using Russell's data for ease of comparison), compiled at 2 p.m., was:[1]

| Went into action strong | Returned from action | Loss | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4th Light Dragoons | 118 | 39 | 79 |

| 8th Hussars | 104 | 38 | 66 |

| 11th Hussars | 110 | 25 | 85 |

| 13th Light Dragoons | 130 | 61 | 69 |

| 17th Lancers | 143 | 35 | 110 |

| Totals | 607 | 198 | 409 |

A formal muster of survivors was also taken: of the 673 cavalrymen who had gone into action, a "mounted strength" of 195 was recorded at this count. This excludes riders whose horses had been lost and so it does not represent the actual casualty numbers. In all, the losses were 113 killed and 134 wounded.[16]

Cardigan survived the battle, although stories circulated that he was not actually present.[17] He led the charge from the front, never looking back, and did not see what was happening to the troops behind him. He reached the Russian guns, took part in the fight, and then returned alone up the valley without bothering to rally or even find out what had happened to the survivors. He afterwards said that all he could think about was his rage against Captain Nolan, who he thought had tried to take over the leadership of the charge. After riding back up the valley, he considered that he had done all that he could. He left the field and boarded his yacht in Balaclava harbour, where he ate a champagne dinner.[18] He described the engagement in a speech delivered at Mansion House, London, which was quoted in the House of Commons:

We advanced down a gradual descent of more than three-quarters of a mile [1.2 km], with the batteries vomiting forth upon us shells and shot, round and grape, with one battery on our right flank and another on the left, and all the intermediate ground covered with the Russian riflemen; so that when we came to within a distance of fifty yards from the mouths of the artillery which had been hurling destruction upon us, we were, in fact, surrounded and encircled by a blaze of fire, in addition to the fire of the riflemen upon our flanks.

As we ascended the hill, the oblique fire of the artillery poured upon our rear, so that we had thus a strong fire upon our front, our flank, and our rear. We entered the battery—we went through the battery—the two leading regiments cutting down a great number of the Russian gunners in their onset. In the two regiments which I had the honour to lead, every officer, with one exception, was either killed or wounded, or had his horse shot under him or injured. Those regiments proceeded, followed by the second line, consisting of two more regiments of cavalry, which continued to perform the duty of cutting down the Russian gunners.

Then came the third line, formed of another regiment, which endeavoured to complete the duty assigned to our brigade. I believe that this was achieved with great success, and the result was that this body, composed of only about 670 men, succeeded in passing through the mass of Russian cavalry of—as we have since learned—5,240 strong; and having broken through that mass, they went, according to our technical military expression, "threes about," and retired in the same manner, doing as much execution in their course as they possibly could upon the enemy's cavalry. Upon our returning up the hill which we had descended in the attack, we had to run the same gauntlet and to incur the same risk from the flank fire of the Tirailleur as we had encountered before. Numbers of our men were shot down—men and horses were killed, and many of the soldiers who had lost their horses were also shot down while endeavouring to escape.

But what, my Lord, was the feeling and what the bearing of those brave men who returned to the position. Of each of these regiments there returned but a small detachment, two-thirds of the men engaged having been destroyed? I think that every man who was engaged in that disastrous affair at Balaklava, and who was fortunate enough to come out of it alive, must feel that it was only by a merciful decree of Almighty Providence that he escaped from the greatest apparent certainty of death which could possibly be conceived.[19]

Aftermath

Summarize

Perspective

The brigade was not completely destroyed, but did suffer terribly, with 118 men killed, 127 wounded, and about 60 taken prisoner.[20] After regrouping, only 195 men were still with horses. The futility of the action and its reckless bravery prompted the French Marshal Pierre Bosquet to state: "C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas la guerre." ("It is magnificent, but it is not war.") He continued, in a rarely quoted phrase: "C'est de la folie"—"It is madness."[21] The Russian commanders are said to have initially believed that the British soldiers must have been drunk.[18] Somerset Calthorpe, the aide-de-camp to Lord Raglan, wrote a letter to a friend three days after the charge. He detailed casualty numbers but did not distinguish between those killed and those taken prisoner:

Killed and missing Wounded 9 Officers 12 14 Sergeants 9 4 Trumpeters 3 129 Rank and file 98 156 Total 122 278 casualties; —besides 335 horses killed in action, or obliged afterwards to be destroyed from wounds. It has since been ascertained that the Russians made a good many prisoners; the exact number is not yet known.[22]

The reputation of the British cavalry was significantly enhanced as a result of the charge, though the same cannot be said for their commanders.

Slow communications meant that news of the disaster did not reach the British public until three weeks after the action. The British commanders' dispatches from the front were published in an extraordinary edition of the London Gazette of 12 November 1854. Raglan blamed Lucan for the charge, claiming that "from some misconception of the order to advance, the Lieutenant-General (Lucan) considered that he was bound to attack at all hazards, and he accordingly ordered Major-General the Earl of Cardigan to move forward with the Light Brigade."[23] Lucan was furious at being made a scapegoat: Raglan claimed he should have exercised his discretion, but throughout the campaign up to that date Lucan considered Raglan had allowed him no independence at all and required that his orders be followed to the letter. Cardigan, who had merely obeyed orders, blamed Lucan for giving those orders. Cardigan returned home a hero and was promoted to Inspector General of the Cavalry.[24]

Lucan attempted to publish a letter refuting point by point Raglan's London Gazette dispatch, but his criticism of his superior was not tolerated, and Lucan was recalled to England in March 1855. The Charge of the Light Brigade became a subject of considerable controversy and public dispute on his return. He strongly rejected Raglan's version of events, calling it "an imputation reflecting seriously on my professional character."[25] In an exchange of public correspondence printed in the pages of The Times, Lucan blamed Raglan and his deceased aide-de-camp Captain Nolan, who had been the actual deliverer of the disputed order. Lucan subsequently defended himself with a speech in the House of Lords on 2 March.[25]

Lucan evidently escaped blame for the charge, as he was made a member of the Order of the Bath in July of that same year. Although he never again saw active duty, he reached the rank of general in 1865 and was made a field marshal in the year before his death.[26]

Evaluation

The charge continues to be studied by modern military historians and students as an example of what can go wrong when accurate military intelligence is lacking and orders are unclear. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who was a keen military historian and a former cavalryman, took time out from the Yalta Conference in 1945 to visit the battlefield.[27]

One research project used a mathematical model to examine how the charge might have turned out if conducted differently. The analysis suggested that a charge toward the redoubt on the Causeway Heights, as Raglan had apparently intended, would have led to even higher British casualties. By contrast, the charge might have succeeded if the Heavy Brigade had accompanied the Light Brigade along the valley, as Lucan had initially directed.[28]

According to Norman Dixon, 19th-century accounts of the charge tended to focus on the bravery and glory of the cavalrymen, much more than the military blunders involved, with the perverse effect that it "did much to strengthen those very forms of tradition which put such an incapacitating stranglehold on military endeavor for the next eighty or so years," i.e., until after World War I.[29]

Fates of the survivors

Summarize

Perspective

The fate of the surviving members of the charge was investigated by Edward James Boys, a military historian, who documented their lives from leaving the army to their deaths. His records are described as being the most definitive project of its kind ever undertaken.[30]

In October 1875, survivors of the charge met at the Alexandra Palace in Middlesex to celebrate its 21st anniversary. The celebrations were fully reported in the Illustrated London News of 30 October 1875,[31] which included the recollections of several of the survivors, including those of Edward Richard Woodham, the Chairman of the Committee that organised the celebration. Tennyson was invited, but could not attend. Lucan, the senior commander surviving, was not present, but attended a separate celebration, held later in the day, with other senior officers at the fashionable Willis's Rooms, St James's Square.[32] Reunion dinners were held for a number of years.[33]

On 2 August 1890, trumpeter Martin Leonard Landfried, from the 17th Lancers, who may[34] have sounded the bugle charge at Balaclava, made a recording on an Edison cylinder that can be heard here, with a bugle which had been used at Waterloo in 1815.[35]

In 2004, on the 150th anniversary of the charge, a commemoration of the event was held at Balaclava. As part of the anniversary, a monument dedicated to the 25,000 British participants of the conflict was unveiled by Prince Michael of Kent.[36]

A survivor, John Penn, who died in Dunbar in 1886, left a personal account of his military career, including the Charge, written for a friend. This survives and is held by East Lothian Council Archives.[37]

Private William Ellis of the 11th Hussars was erroneously described as the last survivor of the Charge at the time of his funeral at Upper Hale Cemetery in Farnham, Surrey in 1913 after his death aged 82.[38][39][40] A number of individuals who died during 1916–17 were thought to be the 'last' survivor of the Charge of the Light Brigade. These include Sergeant James A. Mustard of the 17th Lancers, aged 85, who had his funeral with military honours at Twickenham in early February 1916. In the Abergavenny Chronicle news report published on 11 February 1916, it was stated:

He was one of thirty-eight men of the 145 of the 17th Lancers that came out of the charge led by Cardigan, and was always of the opinion that no one sounded the charge at all. He was in the battles of Alma and Mackenzie's Farm, and the storming and taking of Sebastopol, and before leaving for Varna marched with his regiment from Hampton Court to Portsmouth.[41]

The Cambrian News of 30 June 1916 noted the passing of another 'last', Thomas Warr, who had died the previous day at 85.[42]

William Henry Pennington of the 11th Hussars, who embarked a relatively successful career as a Shakespearean actor on leaving the Army, died in 1923.[40][43] The last survivor was Edwin Hughes of the 13th Light Dragoons, who died on 18 May 1927, aged 96.[44][45]

- Officers and men of the 13th Light Dragoons, survivors of the charge, photographed by Roger Fenton

- Souvenir picture of the 1904 survivors' reunion

- Grave of Charles Macaulay, former Sergeant 8th KRI Hussars "One of the Six Hundred" in Woodhouse Cemetery, Leeds

Remembrance

Summarize

Perspective

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Poet Laureate Alfred, Lord Tennyson, wrote evocatively about the battle in his poem "The Charge of the Light Brigade". Tennyson's poem, written 2 December and published on 9 December 1854, in The Examiner, praises the brigade ("When can their glory fade? O the wild charge they made!") while trenchantly mourning the appalling futility of the charge ("Not tho' the soldier knew, someone had blunder'd ... Charging an army, while all the world wonder'd"). Tennyson wrote the poem inside only a few minutes after reading an account of the battle in The Times, according to his grandson Sir Charles Tennyson. It immediately became hugely popular, and even reached the troops in the Crimea, where 1,000 copies were distributed in pamphlet form.[46]

Nearly 36 years later, Kipling wrote "The Last of the Light Brigade" (1890), commemorating a visit by the last 20 survivors to Tennyson (then aged 80) to reproach him gently for not writing a sequel about the way in which England was treating its old soldiers.[47] Some sources treat the poem as an account of a real event,[48] but other commentators class the destitute old soldiers as allegorical, with the visit invented by Kipling to draw attention to the poverty in which the real survivors were living, in the same way that he evoked Tommy Atkins in "The Absent-Minded Beggar" (1899).[49][50]

There is a lively description of the cavalry charge in the 1862 novel Ravenshoe by Henry Kingsley.[51]

The 1877 novel Black Beauty, written in the first person as if by the horse of the title, includes a former cavalry horse named Captain who describes his experience of being in the Charge of the Light Brigade.

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.