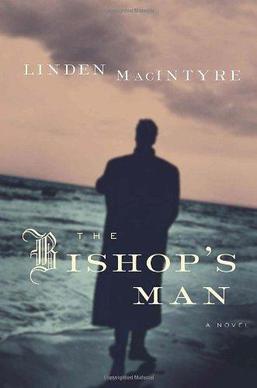

The Bishop's Man

Novel by Canadian writer Linden MacIntyre, 2009 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Bishop's Man is a novel by Canadian writer Linden MacIntyre, published in August 2009. The story follows a Roman Catholic priest and former fixer for the Diocese of Antigonish named Fr. Duncan MacAskill. After years of quietly resolving potential scandals involving the misdeeds of Diocesan priests, Fr. MacAskill has been assigned by his Bishop to a remote parish on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia and ordered to maintain a low profile. MacIntyre, a native of Cape Breton, released the novel amidst the ongoing sexual abuse scandal in Antigonish diocese in Nova Scotia. The book was awarded the 2009 Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Canadian Booksellers Association's Fiction Book of the Year. Critics gave positive reviews, especially noting MacIntyre's complex and successful character development.

| |

| Author | Linden MacIntyre |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fiction novel |

| Publisher | Random House Canada |

Publication date | August 2009 |

| Publication place | Canada |

| Media type | Print (hardcover, paperback) |

| Pages | 399 |

| ISBN | 978-0-307-35706-9 |

| OCLC | 317353345 |

Background

Summarize

Perspective

The Bishop's Man was Linden MacIntyre second novel. His previous novel, The Long Stretch, which was published ten years earlier, in 1999. At the time of the new novel's publication author Linden MacIntyre was 66 years old and living in Toronto with his wife, and fellow journalist and author, Carol Off. MacIntyre was working at CBC Television where he had been the co-host of the fifth estate since 1990. Both The Long Stretch and The Bishop's Man were set on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia where MacIntyre lived as a child. As a child, MacIntyre was raised by an Irish-Catholic mother and attended church regularly where the local priest inspired him to consider entering the priesthood.[1]

The Bishop's Man was published at the same time as a $15 million settlement was reached in the sexual abuse scandal in Antigonish diocese in Nova Scotia. Evidence later emerged that the principal offender, Bishop Raymond Lahey may have similarly assumed the role of a fixer during the sexual abuse scandal in St. John's archdiocese in Newfoundland in 1989 when he served under then-archbishop Alphonsus Liguori Penney.[2] The Bishop's Man is one of the first cultural depictions of the Catholic sexual abuse emerging after the scandal.[3] The term bishop's man has two possible meanings in an ecclesiastical context: it may refer to the title of vicar general who serves as the diocesan bishop's principal deputy for the exercise of administrative authority, or alternatively it may refer to the title of auxiliary bishop, a priest who is consecrated as an episcopal assistant to the local ordinary. In translating real-life situations to fiction MacIntyre stated, "I do believe that the very best of fiction is based on fact...and an awful lot of the factual situations I've been involved with just scream out for creative elaboration."[4]

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

The story follows the protagonist Duncan MacAskill, a priest and the dean of a Catholic university in Nova Scotia. In 1994, his bishop transfers MacAskill to the parish of Creignish, Inverness County, Nova Scotia, and warns him that there are ongoing investigations and he wants MacAskill out of the way before people find him.

MacAskill grew up near Creignish, and begins to slowly adjust to life there where many people seem familiar to him. He befriends Danny MacKay, the son of an acquaintance of his, Danny Ban as well as Danny's maternal aunt Stella. Young Danny is a troubled young man who seems to have a complicated relationship with the church. The feelings between MacAskill and Stella and Danny's erratic behaviour towards the church cause MacAskill to reflect back on his career. In the 70s he witnessed Father Roddie MacVicar, a close friend of the bishop's, molesting a young boy and when he mentioned it to the bishop he was sent to Honduras where he fell in love with a local nurse, Jacinta. Upon his return MacAskill began to be used to cover for priests who had behaved improperly, whether they had impregnated their housekeepers or fallen in love with women to priests who had molested young boys. Part of MacAskill's job in these situations was to assuage angry parents, to tell them it was no use contacting the police, and that the church would punish the rapist, all the while knowing that they would simply be moved to a different parish instead.

In the present, MacAskill continues attempting to reach out to Danny, suspecting that his predecessor, Brendan Bell, now married to a woman, had molested him. Danny continues to behave erratically, and after a fight in which he attempts to attack a local boy who ends up hitting MacAskill, Danny commits suicide. As a result, MacAskill drinks more heavily.

In 1995 MacAskill is contacted by a reporter, MacLeod, about Danny's suicide. MacLeod believes there is a link between Danny and Bell but after MacAskill informs him that Bell is now married to a woman he drops the story. Shortly after though he re-contacts MacAskill to inform him that there was another suicide in British Columbia with affidavits saying that the man who killed himself had been molested by Father Roddie. MacAskill denies knowledge of this though he knows that Roddie was also implicated in the rape of a young girl with an intellectual disability as well. Though MacAskill gives MacLeod no information he begins to drink more heavily causing him to behave in improper ways which include kissing a former acquaintance and stealing liquor. His behaviour is eventually noted by the bishop who sends him to rehab near Toronto, a place where MacAskill knew he often sent other deviants.

After rehab MacAskill tries to contact Bell again. He is eventually able to contact him through a name given to him by his niece who is a journalist. Back in Creignish Bell finally comes to talk to MacAskill. He tells MacAskill that he did know Danny quite well and the boy confided him and even implies that Danny was molested but is unable to provide him with more information than that, telling him to "look closer to home".

Shortly afterwards, while MacAskill is out by the harbour, he comes across Willie Beaton, a local man, who drunkenly admits that he was the one who molested Danny. In anger MacAskill attacks Willie, pushing him so that he falls and injures himself on the rocks. He leaves the scene of the crime, returning to find that Willie has died. Though there is an investigation and a witness who saw MacAskill, MacAskill is let off as Willie's alcohol level was high and the witness was unsure whether MacAskill was moving to help Willie or not. As an act of contrition, MacAskill gives his journals, detailing the numerous cover-ups he participated in, to the police. He sends a letter of resignation to the bishop, who refuses to accepts it. Nevertheless, he decides to leave for a vacation, deciding to stay in Stella's place in the Dominican Republic. Before he goes, Stella admits that she and her sister knew about Danny being molested but decided not to tell his father, as his father would have murdered Willie.

As he is leaving, MacAskill unexpectedly finds Danny Ban in the town's shopping mall. The two men embrace each other as they say their goodbyes.

Characters

- Duncan MacAskill: a Catholic priest who for 20 years specialized in moving around deviant priests for the church

- Danny MacKay: One of Duncan's young parishioners

- Danny Ban: Danny MacKay's father who suffers from multiple sclerosis

- Stella: Danny's aunt, a single woman in Creignish who Duncan grows close to

- Effie: Duncan's sister

- John: Effie's first husband

- Sextus: Effie's second husband

- Brendan Bell: an errant former priest currently married to a woman who was involved in numerous illegal activities

- The Bishop: Duncan MacAskill's bishop who has disdain for the victims of the priests and who works to cover the crimes of priests

- Father Roddie: a priest who molested vulnerable children and a contemporary of The Bishop

- Jacinta: a young married nurse who MacAskill had an affair with in Honduras in the mid-70s

- Alfonso: a priest from Honduras who was MacAskill's best friend and who was mistakenly murdered by Jacinta's husband

Publication and reception

Summarize

Perspective

The Bishop's Man was published by Random House Canada and released in August 2009. It debuted on Maclean's bestsellers list in the August 28 issue at #8. In early October it was included on the shortlist for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and it reached #5 on the bestseller list on October 15. It fell back to the #9 spot on November 5, but returned to #1 for several months after winning the 2009 Scotiabank Giller Prize.[5][6][7] At its Libris Awards, the Canadian Booksellers Association awarded The Bishop's Man its Fiction Book of the Year and Linden MacIntyre its Author of the Year award.[8] The book also won the Atlantic Independent Booksellers' Choice Award and the Dartmouth Book Award (Fiction) from the Atlantic Book Awards Society.[9]

In the Quill & Quire, Quebec writer Paul Gessell said that he found the characters to be "very credible" and "complex" but concluded that "at times, the plot is convoluted and the back-and-forth chronology gets rather tiresome. Generally, however, it is a well-crafted, brave, and painful examination of one of the most monstrous issues of our time."[10] The review in Publishers Weekly found the book to be an "engrossing, lyrical page-turner".[11]

Author Nicholas Pashley reviewed the book for the National Post, writing that "Some readers might find MacIntyre's frequent timeshifting a distraction, but by and large the author handles the various decades of his tale deftly. And as a native Cape Bretoner himself, he brings the region and its residents vividly to life."[12] In the Telegraph-Journal, Sylvie Fitzgerald writes that regarding the characterization "MacIntyre succeeds in demystifying the man beneath the medieval vestments, reminding us that a priest is a man first" and that "MacIntyre's work is resuscitated with colourful local colloquialism".[13]

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.