Starlog

American science fiction magazine (1976–2009) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Starlog was an American monthly science fiction magazine that was created in 1976 and focused primarily on Star Trek at its inception. Kerry O'Quinn and Norman Jacobs were its creators and it was published by Starlog Group, Inc. in August 1976. Starlog was one of the first publications to report on the development of the first Star Wars movie, and it followed the development of what was to eventually become Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979).

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2010) |

| |

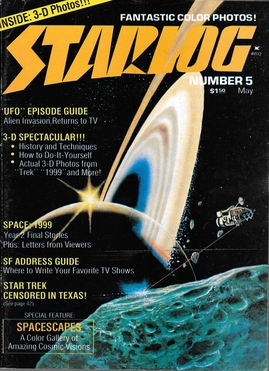

Cover of the May 1977 issue | |

| Editor | David McDonnell |

|---|---|

| Staff writers | Kerry O'Quinn and Norman Jacobs |

| Categories | Science fiction |

| Frequency | Monthly |

| Publisher | Starlog Group, Inc. |

| Founder | Kerry O'Quinn and Norman Jacobs |

| First issue | August 1976 |

| Final issue | April 2009 |

| Company | The Brooklyn Company, Inc. |

| Country | United States |

Starlog was born out of the Star Trek fandom craze, but also was inspired by the success of the magazine Cinefantastique which was the model of Star Trek and Star Wars coverage. Starlog, though it called itself a science fiction magazine, actually contained no fiction. The primary focus of the magazine, besides the fact that it was mostly based on Star Trek fandom, was the making of science fiction media — books, films, and television series - and the work that went into these creations. The magazine examined the form of science fiction and used interviews and features with artists and writers as its foundation.[1]

Science fiction fans, such as those who follow the television channel Syfy, have voiced that Starlog is the science fiction magazine most responsible for cultivating and exhibiting fan culture in America during the magazine's heyday in the 1970s through the early 1990s.[2] Not only did the magazine cover media, the way it was created, and by whom, but they also attended conventions such as the "Ultimate Fantasy" convention in Houston, Texas in 1982 (which was a legendary flop)[3] and kept fans updated on the current events in their respective sci-fi fandoms. Starlog itself followed the marketing strategy of labeling it "the most popular science fiction magazine in publishing history", which allowed the creators to home in on their fanboy market and use that advertisement strategy to their advantage.[1] In later years many of its long-time contributors had moved on.

In April 2009, Starlog officially ended its time in print, moving 33 years of material (374 issues)[4] into the Internet Archive. All of the files had been removed from the Internet Archive by no later than 2022.

History

Summarize

Perspective

Origins

In the mid-1970s, Kerry O'Quinn and his high school friend David Houston talked about creating a magazine that would cover science fiction films and television programs. (O'Quinn and Norman Jacobs had gotten their start in creating and publishing a soap opera magazine.)[5]

O'Quinn came up with the idea of publishing a one-time-only magazine on the Star Trek phenomenon. Houston's editorial assistant, Kirsten Russell, suggested that they include an episode guide to all three seasons of the show, interviews with the cast, and previously unpublished photographs. During this brainstorming session, many questions were raised, most notably legal issues. Houston contacted Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry with the intention of interviewing him for the magazine. Once they got his approval, O'Quinn and Jacobs proceeded to put together the magazine, but Paramount Studios, which owned Star Trek, wanted a minimum royalty that was greater than the startup's projected net receipts, and the project was shelved.

O'Quinn realized they could create a magazine that featured only Star Trek content, but without its being the focus, and thereby circumvent the royalties issue. He also realized this could be the science fiction magazine he and Houston had talked about. Many titles for the new magazine were suggested, including Fantastic Films and Starflight, before Starlog was chosen. (Fantastic Films was later used as the title of a competing science fiction magazine published by Blake Publishing.)

Starlog debuts

The first issue of Starlog, scheduled as a quarterly, was dated August 1976. While the cover featured Captain Kirk, Spock, and the Enterprise, and the issue contained a "Special Collector's Section" on Star Trek, other science fiction topics were also discussed, such as The Bionic Woman and Space: 1999.[6] The issue sold out, and this encouraged O'Quinn and Jacobs to publish a magazine every six weeks instead of quarterly. O'Quinn was the magazine's editor.

Milestones

One of the magazine's milestones was its 100th issue, published in November 1985. It featured the 100 most important people in science fiction as determined by the editors. This included exclusive interviews with John Carpenter, Peter Cushing, George Lucas, Harlan Ellison, Leonard Nimoy, and Gene Roddenberry.[7]

In 1985 and 1986, Starlog teamed with Creation Entertainment to produce a series of conventions called the Starlog SF, Horror & Fantasy Festival. The first show was held March 30–31, 1985, at the Boston Sheraton in Boston.[8] Others were held June 15–16, 1985, at the Center Hotel, Philadelphia, and May 10–11, 1986, at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City.

The magazine's 200th issue repeated the format of the 100th issue, but this time interviewed such notable artists as Arthur C. Clarke, Tim Burton, William Gibson, Gale Anne Hurd, and Terry Gilliam.[9]

The last issue of Starlog, issue 374, published in April 2009 features more modern science fiction media including the television show Fringe, the American movie Push, and the animated stop-motion film Coraline.[10]

Sale to Creative Group, Inc

After the entire magazine industry took a serious tumble in 2001, Starlog Group was eventually purchased by Creative Group, Inc., which continued to publish Starlog and Fangoria, and expanded its franchises into the Internet, satellite radio, TV, and video.

Starlog published its 30th-anniversary issue in 2006.[11]

Warehouse fire

On December 5, 2007, a warehouse operated by Kable News, in Oregon, Illinois, which contained all back issues of Starlog and Fangoria magazines, was destroyed by fire. As back issues of Starlog are not re-printed, the only remaining back issues are now housed in private collections or those available on the secondary market.[12]

Bankruptcy

Starlog publisher Creative Media, including eight affiliates, filed for bankruptcy in March 2008 in the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York, intending to reorganize.[13] By April 2008, it was confirmed that Creative Media was unable to reorganize, and announced that its operations would be sold.[14] and, in June 2008, sold its assets to a group led by private equity firm Scorpion Capital Partners LP. Starlog and Fangoria and all related assets were purchased by The Brooklyn Company, Inc. in July 2008.[15]

In March 2009, Starlog became a sister site to Fangoria magazine's official site, with a new web address tied to Fangoria. Simultaneously, production was halted on issue #375, scheduled for May 2009. New content began to appear on the Starlog website on April 7, 2009, after the site briefly returned to its original Starlog.com domain. The folding of the print edition was officially announced on April 8, 2009, with the unpublished issue promised in the near future as a web-only publication.[16][17] but no such publication ever appeared. By the end of 2009, readers could only access back copies through the Internet Archive; while this worked until at least 2016,[18] the Internet Archive removed the data from its service by no later than 2022, replacing previous links with the statement "This item is no longer available."

In April 2014, Fangoria announced that Starlog would return in the summer of 2014, first as a relaunched website and later in the year as a digital magazine;[19] once again, no such relaunch ever occurred.[18]

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.