2015 Pacific typhoon season

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

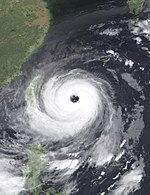

The 2015 Pacific typhoon season was a slightly above average season that produced twenty-seven tropical storms (including two that crossed over from the Eastern/Central Pacific), eighteen typhoons, and nine super typhoons. The season ran throughout 2015, though most tropical cyclones typically develop between May and November. The season's first named storm, Mekkhala, developed on January 15, while the season's last named storm, Melor, dissipated on December 17. The season saw at least one named tropical system forming in each of every month, the first time since 1965. Similar to the previous season, this season saw a high number of super typhoons. Accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) during 2015 was extremely high, the third highest since 1970, and the 2015 ACE has been attributed in part to anthropogenic warming, and also the 2014-16 El Niño event, that led to similarly high ACE values in the East Pacific.[1]

| 2015 Pacific typhoon season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | January 2, 2015 |

| Last system dissipated | December 23, 2015 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Soudelor |

| • Maximum winds | 215 km/h (130 mph) (10-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 900 hPa (mbar) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 38, 1 unofficial |

| Total storms | 27, 1 unofficial |

| Typhoons | 18 |

| Super typhoons | 9 (unofficial)[nb 1] |

| Total fatalities | 349 total |

| Total damage | $14.84 billion (2015 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The scope of this article is limited to the Pacific Ocean to the north of the equator between 100°E and 180th meridian. Within the northwestern Pacific Ocean, there are two separate agencies that assign names to tropical cyclones which can often result in a cyclone having two names. The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA)[nb 2] will name a tropical cyclone should it be judged to have 10-minute sustained wind speeds of at least 65 km/h (40 mph) anywhere in the basin, whilst the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) assigns names to tropical cyclones which move into or form as a tropical depression in the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) located between 135°E and 115°E and between 5°N–25°N regardless of whether or not a tropical cyclone has already been given a name by the JMA. Tropical depressions that are monitored by the United States' Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC)[nb 3][nb 1] are given a number with a "W" suffix.

Seasonal forecasts

Summarize

Perspective

| TSR forecasts Date | Tropical storms | Total Typhoons | Intense TCs | ACE | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (1965–2014) | 26 | 16 | 8 | 294 | [4] |

| May 6, 2015 | 27 | 17 | 11 | 400 | [4] |

| August 5, 2015 | 30 | 20 | 13 | 448 | [5] |

| Other forecasts Date | Forecast Center | Period | Systems | Ref | |

| January 8, 2015 | PAGASA | January — March | 1–2 tropical cyclones | [6] | |

| January 8, 2015 | PAGASA | April — June | 1–3 tropical cyclones | [6] | |

| June 30, 2015 | CWB | January 1 – December 31 | 28–32 tropical storms | [7] | |

| July 6, 2015 | PAGASA | July — September | 7–10 tropical cyclones | [8] | |

| July 6, 2015 | PAGASA | October — December | 3–5 tropical cyclones | [8] | |

| Forecast Center | Tropical cyclones | Tropical storms | Typhoons | Ref | |

| Actual activity: | JMA | 39 | 27 | 18 | |

| Actual activity: | JTWC | 30 | 28 | 21 | |

| Actual activity: | PAGASA | 15 | 14 | 10 | |

During the year several national meteorological services and scientific agencies forecast how many tropical cyclones, tropical storms, and typhoons will form during a season and/or how many tropical cyclones will affect a particular country. These agencies included the Tropical Storm Risk (TSR) Consortium of the University College London, Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) and the Taiwan's Central Weather Bureau. Some of the forecasts took into consideration what happened in previous seasons and the El Niño Conditions that were observed during the year. The first forecast of the year was released by PAGASA during January 2015, within its seasonal climate outlook for the period January – June.[6] The outlook noted that one to two tropical cyclones were expected between January and March while one to three were expected to develop or enter the Philippine Area of Responsibility between April and June.[6]

During March the Hong Kong Observatory predicted that the typhoon season in Hong Kong, would be near normal with four to seven tropical cyclones passing within 500 km (310 mi) of the territory compared to an average of six.[9] Within its Pacific ENSO Update for the 2nd quarter of 2015, NOAA's Pacific El Niño–Southern Oscillation Applications Climate Center, noted that the risk of a damaging tropical cyclone in Micronesia was "greatly enhanced" by El Niño.[10] As a result, they forecasted that the risk of a typhoon severely affecting Micronesia was high, with most islands predicted to have a "1 in 3 chance" of serious effects from some combination of high winds, large waves and extreme rainfall from a typhoon.[10] They also predicted that there was a near 100% chance of severe effects from a typhoon somewhere within Micronesia.[10] On May 6, Tropical Storm Risk issued their first forecast for the season and predicted that the season, would be the most active since 2004 with activity forecast to be above average.[4] Specifically it was forecast that 27 tropical storms, 17 typhoons, and 11 intense typhoons would occur, while an ACE Index of 400 was also forecasted.[4]

Ahead of the Thailand rainy season starting during May, the Thai Meteorological Department predicted that one or two tropical cyclones would move near Thailand during 2015.[11] The first of the two tropical storms was predicted to pass near Upper Thailand in either August or September, while the other one was expected to move to the south of Southern Thailand during November.[11] On June 30, Taiwan's Central Weather Bureau predicted that 28–32 tropical storms would develop over the basin, while two — four systems were expected to affect Taiwan itself.[7] During July, Paul Stanko of the United States National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Tiyan, Guam, called for tropical cyclone activity to be above average.[12] He also predicted that several records would be set for the number of major typhoons in the western Pacific, tropical storms, typhoons and major typhoons in Micronesia.[12] PAGASA subsequently predicted within its July — December seasonal climate outlook, that seven to ten tropical cyclones were likely to develop and/or enter the Philippine area of responsibility between July and September, while three to five were predicted for the October–December period.[8] On July 16, the Guy Carpenter Asia-Pacific Climate Impact Centre (GCACIC) and the City University of Hong Kong's School of Energy, released their seasonal forecast for the period between June 1 – November 30.[13] They predicted that 19.9 tropical cyclones would develop during the period with 10.3 of these going on and making landfall compared to averages of 23.0 and 17.4 tropical cyclones.[13] They further predicted that both the Korea — Japan region and that Taiwan and the Eastern Chinese provinces of Jiangsu, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Fujian would see three of these landfalls each.[13] Vietnam, the Philippines and the Southern Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan were forecasted to see four landfalling tropical cyclones.[13] On August 5, Tropical Storm Risk issued their final forecast for the season and predicted that 2015 would be a hyperactive season.[5] Specifically it was forecast that 30 tropical storms, 20 typhoons, 13 intense typhoons would occur, while an ACE Index of 448 was also forecasted.[5]

Season summary

Summarize

Perspective

Most of the 27 tropical cyclones affected Micronesia, because of the record-tying 2014–16 El Niño event. 2015 opened with Tropical Depression Jangmi (Seniang) from the previous season active within the Sulu Sea, to the north of Malaysia, on January 1, 2015.[14] The system subsequently moved south-eastward, made landfall on Malaysia, and dissipated later that day.[14] However, the official first tropical cyclone of the season was a minor tropical depression, in the same place where Jangmi persisted on January 2, but dissipated two days later.[15] Tropical Storm Mekkhala, on January 13, developed and approached the Philippines where it caused minor damages and also notably interrupted Pope Francis's visit to the country.[15] In early-February, Typhoon Higos developed further east of the basin and reached peak strength of a Category 4 typhoon.[nb 4] Higos became the strongest typhoon on record in the month of February when it broke the record of Typhoon Nancy (1970),[16] and was in turn surpassed by Typhoon Wutip in 2019. During the opening days of March 2015, a major westerly wind burst occurred, which subsequently contributed to the development of the 2014–16 El Niño event and Tropical Storm Bavi.[17] Typhoon Maysak developed and became the most intense pre-April tropical cyclone on record, with maximum 280 km/h (175 mph) 1-minute sustained winds and a minimum pressure of 910 mbar (27 inHg) at its peak intensity.[18] Only one weak system (Haishen) formed in April, which caused little to no damage.[19]

In May, two storms, Typhoons Noul and Dolphin, both reached Category 5 super typhoon intensity.[21] Both typhoons affected landmasses and altogether caused about $37.1 million in damages, respectively. Kujira formed in June and made landfall in southeast Asia, bringing flooding.[22] During the first week of July, the tropics rapidly became active, with a trio typhoons developing simultaneously and affecting three different landmasses. Total damages from Chan-hom, Linfa and Nangka nearly reached US$2 billion. Afterwards, Typhoon Halola entered the basin from the Eastern Pacific.[23] In August, Typhoon Soudelor made landfall in Taiwan and China, where it killed 38 people and damages totaled up to US$3.7 billion[nb 5]. Typhoon Goni badly affected the Philippines, the Ryukyu Islands and Kyushu as an intense typhoon, causing about US$293 million in damages.[24]

In September, Tropical Storm Etau brought flooding in much of Japan, with damages at least US$100 million. Tropical Storm Vamco made landfall over in Vietnam and caused moderate impact and damages. Typhoon Dujuan, similar to Soudelor, impacted China and Taiwan with total damages of $660 million as a Category 4 super typhoon.[25] In early October, Typhoon Mujigae rapidly intensified into a Category 4 typhoon when it made landfall over Zhanjiang, spawning a tornado causing 29 deaths and over US$4 billion in damages. Later, Typhoon Koppu devastated the Philippines as a super typhoon, causing at least $230 million in damages and killing at least 55 people.[26] Typhoon In-fa became a strong typhoon in November, causing minor impact over in the Caroline Islands.[27] In December, Typhoon Melor maintained Category 4 intensity as it passed the Philippine Islands with 42 deaths and US$140 million in damages, while a tropical depression, named Onyok by PAGASA, made landfall in southern Philippines. The final tropical cyclone of the year developed near Malaysia on December 20, and dissipated three days later.[28]

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index for the 2015 Pacific typhoon season as calculated by Colorado State University using data from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center was 462.9 units, which puts it as the fourth-most intense typhoon season since records began in 1950.[29] Broadly speaking, ACE is a measure of the power of a tropical or subtropical storm multiplied by the length of time it existed. It is only calculated for full advisories on specific tropical and subtropical systems reaching or exceeding wind speeds of 39 miles per hour (63 km/h).

Systems

Summarize

Perspective

Severe Tropical Storm Mekkhala (Amang)

Tropical Depression 01W developed during January 13, to the south of Chuuk State.[30][31] Despite convection being displaced from its exposed low-level circulation center (LLCC),[32] the JMA upgraded 01W to a tropical storm with the name Mekkhala, the first of the season.[33] Later, the PAGASA had stated that Mekkhala had entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility, assigning it the local name Amang.[34] By January 15, the JTWC upgraded Mekkhala to a tropical storm when spiral banding wrapped into a defined LLCC.[35][36] Mekkhala intensified to a severe tropical storm when deep convection wrapped into its center during January 16.[37][38] Satellite imagery revealed that a central dense overcast had obscured its center, therefore Mekkhala strengthened into a Category 1 typhoon by the JTWC.[39] Operationally the JMA classified Mekkhala's peak as a typhoon on January 17,[40] however in post-analysis Mekkhala reached its peak as a severe tropical storm.[41] At the time when Mekkhala made landfall over in Eastern Samar, Visayas,[42] land reaction persisted and the typhoon weakened to a tropical storm.[43] By January 18, Mekkhala continued weakening as it started to "unravel and erode" as it passed through the Bicol region in Luzon.[44] Both the JMA and the JTWC issued their final warning later that day.[45][46] However, the JMA continued to monitor Mekkhala until it dissipated early on January 21.[30]

Mekkhala (Amang) had mostly minor impacts in the Philippines. The storm left 3 dead in total in Bicol region and caused about ₱318.7 million (US$7.13 million) in damages.[47] Moreover, the storm caused agricultural damage of ₱30.3 million (US$678,000) in Samar, where it made landfall.[48] Mekkhala also interrupted Pope Francis's visit to the Philippines on January 17.[49]

Typhoon Higos

During February 6, the JMA started to monitor a tropical depression that had developed about 190 km (120 mi) to the northwest of Palikir in Pohnpei State.[50] By February 7, the JTWC started issuing advisories while designating the system as 02W.[51] Deep convection later deepened over in its LLCC and 02W intensified into a tropical storm, with the JMA naming it as Higos.[50][52] Higos started to organize as its convection consolidated and its center became well-defined.[53] The JMA upgraded Higos to a severe tropical storm thereafter.[50] With multiple curved bands wrapping to its center, Higos strengthened into a Category 1 typhoon.[54] The JMA upgraded Higos to a typhoon early on February 9.[55] Higos explosively intensified through the course of 24 hours and on February 10, Higos reached its peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds of 240 km/h (150 mph), making it the first super typhoon of the season. Later, Higos rapidly weakened; its eye dissipated and convection became less organized, so the JMA downgraded Higos to a severe tropical storm.[50][56] By February 11, Higos further weakened to a tropical storm as its center became fully exposed.[50][57] Both agencies issued their final warning later that day and Higos fully dissipated on February 12.[50][58]Higos was the most powerful February typhoon at the time until Typhoon Wutip surpassed it in 2019.[59]

Tropical Storm Bavi (Betty)

Tropical Storm Bavi was first noted as a tropical disturbance during March 8, while it was located 500 km (310 mi) to the southeast of Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands.[60] Over the next few days the system moved north-westwards through the Marshall Islands, and was classified as a tropical depression during March 10.[61] The system continued to develop over the next day as it moved north-westwards, before it was classified as a tropical storm and named Bavi by the JMA.[61] The system subsequently continued to gradually intensify as it moved westwards, around the southern periphery of the subtropical ridge of high pressure located to the northwest of the system.[61][62] During March 14, the system peaked as a tropical storm with the JMA reporting 10-minute sustained winds of 85 km/h (55 mph), while the JTWC reported 1-minute sustained winds of 95 km/h (60 mph).[61][63] As the system subsequently started to weaken the system's low level circulation passed over Guam during March 15, while convection associated with the system passed over the Northern Mariana islands.[17][64] Over the next couple of days the system moved westwards and continued to weaken, before it weakened into a tropical depression during March 17, as it moved into the Philippine area of responsibility, where it was named Betty by PAGASA.[61][65] The JTWC stopped monitoring Bavi during March 19, after the system had weakened into a tropical disturbance, however, the JMA continued to monitor the system as a tropical depression, until it dissipated during March 21.[61][63]

Tropical Storm Bavi and its precursor caused severe impacts in Kiribati.[66] Bavi and its precursor tropical disturbance impacted eastern Micronesia, with strong to gale-force winds of between 45–65 km/h (30–40 mph), reported on various atolls in the Marshall Islands.[67] Considerable damage was reported on the islet of Ebeye while on the main atoll of Kwajalein, a small amount of tree damage was reported and several old steel structures were made too dangerous to use.[67] Overall damages in the Marshall Islands were estimated at over US$2 million, while a fishing vessel and its crew of nine were reported missing during March 12.[67] After impacting Eastern Micronesia, Bavi approached the Mariana Islands, with its circulation passing over Guam during March 15, where it caused the highest waves to be recorded on the island in a decade.[64] Bavi also impacted the Northern Mariana Islands of Rota, Tinian and Saipan, where power outages were reported and five houses were destroyed.[64][68] Total property damages within the Mariana Islands, were estimated at US$150 thousand.[64]

Typhoon Maysak (Chedeng)

A day after Bavi dissipated, a low-pressure area formed southwest of the Marshall Islands. It slowly drifted northwestward and became more organized over the next two days.[69] The next day, the JMA started tracking the system as a tropical depression.[70] On March 27, the JTWC started tracking the system as a tropical depression, and designated it 04W.[71] Moving west-northwestward, the system's center became more consolidated with convective banding becoming wrapped into it. The JTWC upgraded 04W to a tropical storm the same day.[72] The JMA followed suit later that day, when it was named Maysak.[73] On March 28, Maysak developed an eye,[74] and the JMA further upgraded it to a severe tropical storm.[75] The eye became more well defined with deep convection persisting along the southern quadrant of the storm. The overcast became more consolidated,[76] as the JMA upgraded Maysak to a typhoon on the same day.[77] On March 29, Maysak rapidly intensified over a period of 6 hours, attaining 1-min maximum sustained winds of 230 km/h (145 mph), making it a Category 4 equivalent on the SSHWS.[78] On the next day, Maysak further intensified into a Category 5-equivalent super typhoon.[citation needed] On April 1, the PAGASA stated tracking on the system, naming it as Chedeng. Typhoon Chedeng (Maysak) weakened more and eventually dissipated in the Luzon landmass. The remnants of Maysak eventually made it to the South China Sea.[79]

Typhoon Maysak passed directly over Chuuk State in the Federated States of Micronesia on March 29, causing extensive damage. High winds, measured up to 114 km/h (71 mph) at the local National Weather Service office, downed numerous trees, power lines, and tore off roofs. An estimated 80–90 percent of homes in Chuuk sustained damage. Power to most of the island was knocked out and communication was difficult. Early reports indicated that five people had died.[80]

Tropical Storm Haishen

By March 29, the JTWC started to monitor a tropical disturbance over the Marshall Islands, and later upgraded it to a "low chance" of being a cyclone two days later.[81] Best track indicated that the system developed into a tropical depression during April 2,[82] but operationally the JMA did so on April 3.[83] Shortly thereafter, the JTWC designated the system to 05W, when 1-minute winds stated that it had strengthened into a tropical depression.[84] 05W started to organize with a slight consolidation of its LLCC and some convective banding; the JTWC upgraded 05W to a tropical storm.[85] The JMA did the same later, when it was given the name Haishen.[86] Haishen remained at low-level tropical storm strength until its center became fully exposed with its deepest convection deteriorating due to wind shear.[87] Both the JMA and JTWC stopped monitoring the system during April 6, as it dissipated over open waters to the southeast of the Mariana Islands.[82]

In Pohnpei State, 118 mm (4.66 in) worth of rain was recorded on the main island between April 2–3, however, there was no significant damage reported in the state.[88] During April 4, the system passed to the north of Chuuk and Fananu in Chuuk State, while wind and rain associated with Haishen passed over the area.[88] There were no direct measurements, of either the wind or rainfall made on Fananu, however, it was estimated that tropical storm force winds of 40–52 mph (64–84 km/h) were experienced on the island.[88] It was also estimated that 100–150 mm (4–6 in) of rainfall fell on the island, while islanders confirmed that periods of heavy rain did occur.[88] Haishen knocked down several fruit trees on Fananu, while the heavy rains were considered to be a positive blessing, as they restored water levels on the island, that had been damaged a few days earlier by Maysak.[88] There were no reports of any other significant damage in the state, while property and crop damage were both estimated at US$100,000.[88]

Typhoon Noul (Dodong)

On April 30, a tropical disturbance developed near Chuuk.[89] On May 2, the JMA began to track the system as a weak tropical depression.[90] The following day, the JMA upgraded the depression to a tropical storm and assigned the name Noul.[91] On May 5, the JMA upgraded the system to a severe tropical storm while the JTWC upgraded it to a minimal typhoon.[92] The following day, the JMA also upgraded Noul to a typhoon.[citation needed] Early on May 7, Noul entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility and was assigned the name Dodong by PAGASA.[93] Later that day, the JTWC upgraded Noul to a Category 3 typhoon as a small eye had developed.[94] At the same time, according to Jeff Masters of Weather Underground, Noul had taken on annular characteristics.[95] Although Noul weakened to a Category 2 typhoon early on May 9, six hours later, the JTWC upgraded Noul back to a Category 3 typhoon, as its eye became clearer and well-defined. The JTWC upgraded Noul to a Category 4 super typhoon later that day after it began rapid deepening.[citation needed] On May 10, the JTWC further upgraded Noul to a Category 5 super typhoon, and the JMA assessed Noul with 10-minute sustained winds of 205 km/h (125 mph) and a minimum pressure of 920 mbar, its peak intensity.[96][97] Later that day, Noul made landfall on Pananapan Point, Santa Ana, Cagayan.[98] After making a direct hit on the northeastern tip of Luzon, the storm began to weaken, and the JTWC downgraded it to a Category 4 super typhoon.[99] Subsequently, it began rapidly weakening and by May 12, it had weakened to a severe tropical storm.[citation needed]

Typhoon Dolphin

On May 3, a tropical disturbance south southeast of Pohnpei began to organize, and the JMA upgraded the disturbance into a tropical depression.[100] Late on May 6, the JTWC started issuing advisories and designated it as 07W.[101] On May 9, the JMA upgraded the depression into a tropical storm and named it Dolphin.[102] The JMA further upgraded Dolphin to a severe tropical storm on May 12,[103] and on the following day, the JTWC upgraded Dolphin to a typhoon.[104] Six hours later, the JMA had followed suit.[105] Over the next few days, Dolphin continued to intensify until it reached Category 5 super typhoon status on May 16. It weakened into a category 4 super typhoon 12 hours later, until it weakened into a category 4 equivalent typhoon after maintaining super typhoon status for 30 hours. Dolphin weakened further into a severe tropical storm on May 19, as the JTWC downgraded Dolphin into a tropical storm and issued their final warning. On May 20, the JMA issued their final warning, and the JTWC and the JMA declared that Dolphin had become an extratropical cyclone.[106][107]

Tropical Storm Kujira

During June 19 the JMA started to monitor a tropical depression that had developed within the South China Sea about 940 km (585 mi) to the southeast of Hanoi, Vietnam.[108] Over the next day the system gradually developed further before the JTWC initiated advisories on the system and designated it as Tropical Depression 08W.[109] Deep convection obscured its low-level circulation center; however, upper level analysis indicated that 08W was in an area of moderate vertical windshear.[110] On June 21, the JMA had reported that 08W had intensified into a tropical storm, naming it Kujira.[111][112] Kujira slightly intensified and the JTWC finally upgraded the system to a tropical storm by June 22.[113][114] In the same time, Kujira's circulation became exposed but convection remained stable.[115] Therefore, according to both agencies, Kujira reached its peak intensity with a minimum pressure of 985 mbar later in the same day.[116] Kujira would've been a severe tropical storm but because of displaced convection and moderate to high windshear, the storm began a weakening trend.[117] The JTWC downgraded Kujira to a tropical storm as it was located in an area of very unfavorable environments early on June 23;[118] however, by their next advisory it was reported that Kujira entered an area of warm waters and was upgraded back to tropical storm status.[119] During June 24, Kujira made landfall on Vietnam to the east of Hanoi and weakened into a tropical depression.[108] The system was subsequently last noted during the next day, as it dissipated to the north of Hanoi.[108]

Although outside the Philippine area of responsibility, Kujira's circulation enhanced the southwest monsoon and marked the beginning of the nation's rainy season on June 23, 2015.[120] Striking Hainan on June 20, Kujira produced torrential rain across the island with an average of 102 mm (4.0 in) falling across the province on June 20; accumulations peaked at 732 mm (28.8 in). The ensuing floods affected 7,400 hectares (18,000 acres) of crops and left ¥85 million (US$13.7 million) in economic losses.[121] Flooding in northern Vietnam killed at least nine people, including eight in Sơn La Province, and left six others missing.[122] Across the country, 70 homes were destroyed while a further 382 were damaged.[123] Preliminary estimated damage in Vietnam were at ₫50 billion (US$2.28 million).[124]

Typhoon Chan-hom (Falcon)

On June 25, the JTWC started to monitor a weak tropical disturbance embedded in the active ITCZ.[125] Convection increased within the system as the JMA and the JTWC upgraded the system to a tropical depression on June 30 while it was located near the island of Kosrae.[126][127] Later that day, the JMA upgraded the depression to a tropical storm and assigned the name Chan-hom.[128] Although it was upgraded to a typhoon on July 1,[129][130] increasing wind shear caused the system to weaken back into a tropical storm as it neared Guam.[131][132]

On July 5, as it started to move north then northwest, Chan-hom showed good outflow aloft and low vertical windshear was within the area.[133] Both agencies upgraded the storm to a typhoon again on July 6, as an eye developed.[134][135][136] On July 7, PAGASA had reported that Chan-hom had entered their Area of Responsibility and was assigned the name Falcon.[137] With a clear and defined eye and an expanding gale-force winds,[138][139][140] both agencies classified Chan-hom as a Category 4 typhoon on July 9,[141] with a 10-minute wind peak of 165 km/h (105 mph) and a minimum pressure of 935 millibars.[142] On July 10, Chan-hom further weakened as an eyewall replacement cycle developed with moderate to high vertical windshear as it neared eastern China.[143][144] Chan-hom made landfall southeast of Shanghai later that day.[145] Because of cooler waters, Chan-hom weakened below typhoon status.[146][147] During July 12, Chan-hom briefly transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, before it dissipated over North Korea during the next day.[148]

Ahead of the typhoon's arrival in East China, officials evacuated over 1.1 million people.[149] Even though Chan-hom did not affect the Philippines, the typhoon enhanced the southwest monsoon which killed about 16 people and damages of about ₱3.9 million (US$86,000).[150]

Severe Tropical Storm Linfa (Egay)

Just as soon as the tropics began to activate, the Intertropical Convergence Zone span four tropical systems across the Western Pacific, and a tropical disturbance had formed about 1,015 km (631 mi) east-southeast of Manila during June 30.[151] By July 1, the JMA started to track the system as it was classified as a tropical depression.[152] During the next day, the JTWC followed suit and assigned the designation of 10W,[153] while PAGASA named 10W as Egay.[154] Few hours later, Egay strengthened into a tropical storm, with the name Linfa given from the JMA.[155][156] Despite an exposed center, associated convection was being enhanced by its outflow, and Linfa intensified into a severe tropical storm.[157][158] Late on July 4, Linfa made landfall over in Palanan, Isabela while maintaining its intensity.[159][160] Linfa crossed the island of Luzon and emerged to the South China Sea while it began moving in a north-northwestward direction.[161] By July 7, Linfa had become slightly better organized.[162] PAGASA issued its final bulletin on Linfa (Egay) as it exited their area of responsibility.[163] Linfa entered in an area of favorable environments with good banding wrapping into its overall structure,[164] and Linfa strengthened into a Category 1 typhoon by the JTWC as an eye developed and tightly curved banding started to wrap its LLCC.[165] During July 9, Linfa made landfall in Guangdong Province of China.[166][167] Thereafter, Linfa experienced land interaction and rapidly weakened and both agencies issued their final advisories on July 10.[168][169]

Across Luzon, Linfa damaged 198 houses and destroyed another seven. The storm damaged ₱34 million (US$753,000) worth of crops, and total damage reached ₱214.65 million (US$4.76 million).[170] Most of the power outages were repaired within a few days of Linfa's passage. According to estimates in southern China, economic losses from the storm reached ¥1.74 billion (US$280 million).[121] A total of 288 homes collapsed and 56,000 people were displaced.[171] A gust of 171 km/h (106 mph) was observed in Jieyang.[172] A storm surge of 0.48 m (1.6 ft) was also reported along Waglan Island and rainfall reached a total of around 40 millimetres (1.6 in) in the territory.[166]

Typhoon Nangka

On July 3, the JMA started to monitor a tropical depression over the Marshall Islands.[173] Later that day, was designated as 11W by the JTWC as it started to intensify.[174] The JMA followed suit of upgrading it to a tropical storm, naming it Nangka.[175] After three days of slow strengthening, Nangka was upgraded to a severe tropical storm on July 6, because of favorable environments such as a symmetrical cyclone, an improving outflow and low vertical windshear .[176][177] Shortly afterwards, rapid intensification ensued and Nangka was upgraded to a Category 2 typhoon 24 hours later.[178][179] The intensification trend continued, and Nangka reached its first peak as a Category 4 typhoon as an eye developed.[180][181]

Shortly after its first peak, Nangka slightly weakened and its eye became cloud-filled.[182] Although some vertical wind shear initially halted the intensification trend, the storm resumed intensifying on July 9, and was upgraded to a Category 4 super typhoon with 1-minute sustained winds of 250 km/h (155 mph). In the same time, Nangka's structure became symmetrical and its eye re-developed clearly.[183][184][185] The JMA also assessed Nangka's peak with 10-minute winds of 185 km/h (115 mph).[186] Nangka maintained super typhoon strength for 24 hours before weakening to a typhoon on July 10 as it entered an area of some unfavorable environments.[187] Nangka weakened to a Category 1-equivalent typhoon on July 11, but began strengthening again late on July 12, reaching a secondary peak as a Category 3-equivalent typhoon as its eye became clear once more.[188][189] An eyewall replacement cycle interrupted the intensification the following day, and Nangka weakened because of drier air from the north.[190][191] At around 14:00 UTC on July 16, Nangka made landfall over Muroto, Kōchi of Japan.[192] A few hours later, Nangka made its second landfall over the island of Honshu, as the JMA downgraded Nangka's intensity to a severe tropical storm.[192][193][194] Because of land reaction and cooler waters, Nangka's circulation began to deteriorate and was downgraded to a tropical depression by both agencies late on July 17.[195][196] On July 18, both agencies issued their final warning on Nangka as it weakened to a remnant low.[197][198]

On Majuro atoll in the Marshall Islands, high winds from Nangka tore roofs from homes and downed trees and power lines. Nearly half of the nation's capital city of the same name were left without power. Tony deBrum, the Marshall Island's foreign minister, stated "Majuro [is] like a war zone."[199] At least 25 vessels in the island's lagoon broke loose from or were dragged by their moorings. Some coastal flooding was also noted.[199]

Typhoon Halola (Goring)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 13 (Entered basin) – July 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (10-min); 955 hPa (mbar) |

During July 13, Tropical Storm Halola moved into the Western Pacific basin from the Central Pacific basin, and was immediately classified as a severe tropical storm by the JMA.[200] Over the next day the system moved westwards and gradually intensified, before it was classified as a typhoon during the next day.[200][201] Later that day, both the JMA and JTWC reported that Halola reached peak intensity as a Category 2 typhoon.[202][203] However weakening convection and moderate vertical windshear caused the typhoon to weaken on July 15.[204][205] Halola further weakened to a tropical depression as the JMA issued its final advisory on July 18; however, the JTWC continued tracking Halola.[206][207]

On July 19, the JMA re-issued advisories and Halola showed signs of further intensification.[208][209] An improved convective signature, expanding moisture field and shallow banding wrapped into the system prompted both agencies to upgrade it to a tropical storm early on July 20.[210][211] Halola intensified into a typhoon again the next day, as the typhoon became more symmetrical than before.[212][213][214] By July 22, Halola reached its second peak intensity as a Category 2 typhoon, but this time it was a little stronger with 10-minute sustained winds of 150 km/h (95 mph).[200][215][216] PAGASA reported that Halola entered their Area of Responsibility receiving the name Goring early on July 23.[217][218] On the next day, Halola encountered northeasterly vertical windshear as the system started to weaken.[219] During July 25 and 26, Halola weakened to tropical storm strength and passed the southwestern Japanese Islands.[220] At around 09:30 UTC on July 26, Halola made landfall over Saikai, Nagasaki of Japan.[221] The system was subsequently last noted later that day as it dissipated in the Sea of Japan.[200]

Throughout the Daitō Islands, sugarcane farms were significantly affected by Typhoon Halola, resulting damage of about ¥154 million (US$1.24 million).[222]

Tropical Depression 12W

During July 23, the JMA and JTWC started monitoring Tropical Depression 12W, that had developed to the northeast of Manila, Philippines.[223][224] Over the next day the system moved towards the north-northeast along the subtropical ridge, in an environment that was considered marginal for further development.[225] During the next day, despite Dvorak estimates from various agencies decreasing because of a lack on convection surrounding the system, the JTWC reported that the system had become a tropical storm, with peak 1-minute sustained winds of 65 km/h (40 mph).[226][227] This was based on an image from the advanced scatterometer, which showed winds of 65–75 km/h (40–45 mph) along the system's western periphery.[226] The system subsequently directly interacted with Typhoon Halola, before increased vertical wind shear and subsidence from the interaction caused the depression to deteriorate.[228][229] As a result, the system's low level circulation became weak and fully exposed, with deep convection displaced to the system's western half, before it was last noted during July 25, as it dissipated to the east of Taiwan.[227][228]

Typhoon Soudelor (Hanna)

During July 29, the JMA reported that a tropical depression had developed, about 1,800 km (1,120 mi) to the east of Hagåtña on the island of Guam.[230] Over the next day the system moved westwards under the influence of the subtropical ridge of high pressure and quickly consolidated, in an environment that was marginally favorable for further development.[231] As a result, the JTWC initiated advisories and designated it as Tropical Depression 13W during July 30.[231] In the same day, Soudelor showed signs of rapid intensification as a central dense overcast obscured its LLCC.[232] Therefore, the JMA upgraded Soudelor to a severe tropical storm on August 1. Intensification continued, and both agencies upgraded Soudelor to a typhoon the next day. On August 3, Soudelor further deepened into a Category 5 super typhoon with 285 km/h (175 mph) 1-minute sustained winds, and the JMA assessed Soudelor with 10-minute sustained winds of 215 km/h (135 mph) and a minimum central pressure of 900 millibars, making Soudelor the strongest typhoon since Typhoon Vongfong at the time.[233] The typhoon maintained its peak intensity for 18 hours until it began to weaken gradually on 15:00 UTC on August 4.[234] The next day, PAGASA noted that Soudelor had entered the Philippine area of responsibility, naming it Hanna.[235] On August 7, Soudelor re-intensified into a Category 3-equivalent typhoon as it entered an area of favorable conditions.[236][237]

On August 2, Soudelor made landfall on Saipan as a Category 4 typhoon resulting in severe damage, with early estimates of over $20 million (2015 USD) in damages.[238] On August 8, at around 4:40 AM, Soudelor made landfall to the north of Hualien as a Category 3 storm.[citation needed]

Tropical Depression 14W

During August 1, the JMA reported that a tropical depression had developed, about 940 km (585 mi) to the southeast of Tokyo, Japan.[239] The system had a small low level circulation center, which was partially exposed, with deep atmospheric convection located over the systems southern quadrant.[240] Overall the disturbance was located within a favourable environment for further development, with favourable sea surface temperatures and an anticyclone located over the system.[240] During the next day, the system was classified as Tropical Depression 14W by the JTWC, while it was located about 740 km (460 mi) to the southeast of Yokosuka, Japan.[241]

Because of a well-defined but an exposed low-level circulation center with deep flaring convection over the storm's eastern periphery, the JTWC upgraded the system to a tropical depression, designating it as 14W.[242] The JTWC issued its final warning on the system during August 4, after an image from the advanced scatterometer showed that 14W had a weak circulation that had fallen below their warning criteria.[243] However, the JMA continued to monitor the system, before it was last noted during the next day while it was affecting Kansai region.[citation needed]

Tropical Storm Molave

During August 6, the JMA started to monitor a tropical depression that had developed about 680 km (425 mi) to the northeast of Hagåtña, Guam.[244] The system was located within an area that was considered moderately favorable for further development, with low to moderate vertical windshear and a good outflow.[245] Over the next day, convection wrapped around the system's low-level circulation and the system gradually consolidated, before a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert was issued by the JTWC later during that day.[245][246]

Early on August 7, the JTWC upgraded the system to Tropical Depression 15W.[247] On the same day, 15W gradually intensified, and was named Molave by the JMA.[248] The JTWC kept Molave's intensity to a weak tropical depression of 25 knots because of poorly and exposed circulation.[249][250] However the JTWC upgraded Molave to a tropical storm on August 8, as deep convection and tropical storm force winds were reported in the northwestern side of the system.[251] During the next day, Molave entered in an area of marginally favorable conditions with low to moderate vertical wind shear, with its circulation becoming partially exposed.[252] Hours later, deep convection rapidly diminished and the JTWC declared it to be a subtropical storm and issued its final advisory.[253] Despite weakening to a subtropical storm, the JMA still classified Molave at tropical storm strength.[244]

On August 11, according to the JTWC, strengthened back into a tropical storm and re-issued advisories.[254][255] Molave's convection weakened due to strong shear as its LLCC became fully exposed.[256] Later that day, Molave weakened to minimum tropical storm strength.[257] On August 13, deep convective was fully sheared and Molave drifted deeper into the mid-latitude westerlies.[258] The JTWC later issued its final warning as environmental analysis revealed that Molave is now a cold-core extratropical system.[259] Early on August 14, the system degenerated into an extratropical cyclone, before it was last noted by the JMA moving out of the Western Pacific during August 18.[244]

Typhoon Goni (Ineng)

On August 13, the JMA started to monitor a tropical depression that had developed, about 685 km (425 mi) to the southeast of Hagåtña, Guam.[260] By the next day, the depression started to organize and was designated as 16W by the JTWC.[261] Several hours later, deep convection had improved and has covered its LLCC and both agencies upgraded 16W to a tropical storm, naming it Goni.[262][263] During the night of August 15, the JMA upgraded Goni to a severe tropical storm as windshear started to calm whilst deep convective banding wrapping into its circulation.[264][265] By the next day, satellite imagery depicted a developing eye with an improved tightly curved banding which upper-level analysis revealed that low shear and an improving environment.[266] Goni intensified into a typhoon by both agencies a few hours later.[267][268] Early on August 17, satellite imagery depicted a small-pinhole eye as Goni underwent rapid intensification and was upgraded rapidly to a Category 4 typhoon and reached its first peak intensity.[269] Slightly thinning convective banding and low to moderate wind shear caused Goni to weaken to a Category 3 typhoon.[270] Goni maintained that intensity while moving westward and entered the Philippine's area which PAGASA gave the name Ineng,[271] until on August 19, Goni entered an area of favorable environments. Goni had maintained an overall convective signature with tightly curved banding wrapping into a 28 nautical-mile eye.[272] The JTWC later re-upgraded Goni back at Category 4 typhoon status early on August 20 as it neared the northeastern Philippine coast.[citation needed]

Typhoon Atsani

Shortly after beginning to track the precursor to Goni, the JTWC started to track another tropical disturbance approximately 157 km (100 mi) north-northwest of Wotje Atoll in the Marshall Islands.[273] Deep convection with formative bands surrounding the system's circulation caused both the JMA and the JTWC to upgrade it to a tropical depression, also designating it as 17W on August 14.[274][275] Later that day, both agencies upgraded 17W to a tropical storm, with the JMA naming it Atsani.[276] On August 16, both agencies upgraded Atsani to a typhoon as it was found in microwave imagery that an eye was developing.[277][278] Improved convective banding and a ragged eye formed by early the next day.[279] That night, the typhoon's eye became well-defined and the JTWC assessed Atsani's intensity an equivalent to a Category 3 storm.[280] Deepening of convection continued until early on August 18, when the JTWC upgraded Atsani to a Category 4 typhoon.[281] By August 19, very low vertical windshear and excellent radial outflow were in place. A symmetric core and extra feeder bands prompted the JTWC to upgrade it to a super typhoon.[282] Later that day, satellite imagery showed that Atsani was more symmetric and deep with feeder bands wrapping tighter into an expanded 34 nautical-mile diameter eye. Therefore, the JTWC upgraded Atsani further to a Category 5 super typhoon and it attained its peak intensity of 1-minute sustained winds of 260 km/h (160 mph).[283]

Atsani moved in a northwestward direction as it was later downgraded to a Category 4 super typhoon intensity on August 20[284] and at typhoon category later that day as it weakened further.[285] On August 21, satellite imagery indicated that convection over Atsani was decreasing and an eyewall replacement cycle occurred, therefore, the JTWC downgraded Atsani further to a Category 3 typhoon.[286][287] Vertical windshear started to intensify to a moderate scale and dry air persisted within the north and western part of Atsani and its eyewall began to erode.[288][289] By the next day, significant dry air prohibited intensification and multispectral satellite imagery indicated a warming in the typhoon's cloud tops prompted the JTWC to downgrade it to a Category 1 typhoon.[290] Atsani maintained that intensity as it started to move in a northeastward direction and began to interact with higher vertical wind shear associated by the mid-latitude baroclinic zone late on August 23.[291] On August 24, the JMA downgraded Atsani to a severe tropical storm.[292] A few hours later, the JTWC followed suit of downgrading the typhoon to tropical storm strength.[293] The JTWC issued its final warning later that day;[294] During August 25, Atsani became an extra-tropical cyclone, while it was located about 1,650 km (1,025 mi) to the northeast of Tokyo, Japan. The next day, the storm absorbed the remnants of Hurricane Loke in the Eastern Pacific. The system was subsequently last noted as it dissipated during August 27.[295]

Typhoon Kilo

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 1 (Entered basin) – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (10-min); 950 hPa (mbar) |

During September 1, Hurricane Kilo moved into the basin from the Central Pacific and was immediately classified as a typhoon by the JMA and the JTWC.[296][297] During the next day, Kilo started to encounter moderate vertical wind shear and started weakening.[298] After briefly re-strengthening,[299] by September 4, moderate to high southwesterly wind shear prohibited development.[300][301] Later that day, Kilo developed an eye again; however, the typhoon maintained its same intensity,[302] and later became ragged on September 6.[303]

On September 7, the JTWC estimated winds of 165 km/h (105 mph), which again made its wind equal to that of Category 2 hurricane for a brief time.[304] Later that day, Kilo started to weaken as its eye became irregular with eroding convection over the southern semi-circle of the typhoon.[305] Deep convection started to decay, as the JTWC reported a few hours later.[306] Late on the next day, the Kilo's convective signature began to degrade due to drier air wrapping to its core, forcing the JTWC to lower Kilo's intensity.[307] On September 9, the JMA downgraded Kilo to a severe tropical storm.[308] The JTWC followed suit several hours later as the center became exposed from the deep convection;[309] Kilo was located in an area of strong shear.[310] Thereafter, Kilo began to undergo extratropical transition as the JTWC issued its final warning early on September 11.[311][312] Hours later, the JMA reported that Kilo had transitioned into an extratropical cyclone.[313] The extratropical remnants of Kilo later affected the Kamchatka Peninsula and the Aleutian Islands. The system moved out of the basin on September 13 and was last noted over Alaska roughly two days later.[296]

Severe Tropical Storm Etau

On September 2, a tropical disturbance developed 560 km (350 mi) to the northwest of the island of Guam. Moving towards the northwest,[314] post-analysis from the JMA showed that Etau formed early on September 6.[315] The following day, the JMA upgraded the depression to a tropical storm[316] while the JTWC upped it to a tropical depression following an increase in organization.[317] Satellite image revealed that convection was increasing in coverage,[318] causing the JTWC to upgrade it to a tropical storm.[319] A banding eye feature developed on September 8,[320] and therefore the JMA upgraded Etau to a severe tropical storm.[321] Despite strong wind shear due to a trough, Etau maintained its intensity.[322] Late on the same day, following an increase in convection, the JTWC assessed Etau's intensity to 55 knots.[323] Early on September 9, Etau made landfall over central Honshu and in the same time, Etau weakened to tropical storm strength whilst the JTWC issued its final advisory.[324][325] The JMA finally issued its final bulletin on Etau later that day once extratropical transition was completed.[326] The remnants of Etau was absorbed by another extratropical system that was formerly Typhoon Kilo on September 11.[315]

When Etau affected Japan, particularly Honshu, during September 8–9, the storm brought widespread flooding. Record rains fell across many areas in eastern Japan, with more than 12 in (300 mm) reported in much of eastern Honshu.[327] The heaviest rains fell across Tochigi Prefecture where 668 mm (26.3 in) was observed in Nikkō, including 551 mm (21.7 in) in 24 hours.[327] Fukushima Prefecture saw its heaviest rains in 50 years, with more than 300 mm (12 in) observed during a 48‑hour span.[328] Nearly 3 million people were forced to leave their homes. In total, eight people were killed and total damages were amounted to ¥11.7 billion (US$97.8 million).[329] On September 10, the remnants of Etau brought some rainfall and gusty winds over in the Russian Far East region.[330]

Tropical Storm Vamco

On September 10, a tropical disturbance formed within the monsoon 560 km (350 mi) west of Manila.[331] The disturbance meandered for a few days and was later classified as a tropical depression by the JMA on September 13.[332] With flaring deep convection surrounding the center, the JTWC upgraded it to a tropical depression.[333][334] Shortly after that, both the JMA and the JTWC upgraded it to a tropical storm.[335][336] Due to increased wind shear, the center of Vamco became partially exposed on September 14.[337] Therefore, the JTWC issued its final warning.[338] The JMA later downgraded Vamco to a tropical depression and issued their final advisory early on September 15.[339] The remnants of Vamco continued to move in a westward direction inland and crossed the 100th meridian east on September 16.[citation needed]

Vamco made landfall south of Da Nang, Vietnam, which caused floods across parts of the country.[340] Flooding in Vietnam killed 11 people.[341] Losses to fisheries in the Lý Sơn District exceeded ₫1 billion (US$44,500).[342] Damage to the power grid in Vietnam reached ₫4.9 billion (US$218,000).[343] In Quảng Nam Province, Vamco caused moderate damage. In Duy Xuyên District, agricultural losses exceeded ₫2 billion (US$89,000) and in Nông Sơn District total damage is ₫1 billion (US$44,500).[344] Officials in Thanh Hóa Province estimated total damages from the flooding by the storm had reached ₫287 billion (US$12.8 million).[345] Flooding in Cambodia affected thousands of residents and prompted numerous evacuations.[346] The remnants of Vamco triggered flooding in 15 provinces across Thailand and killed two people.[347][348] At least 480 homes were damaged and losses exceeded ฿20 million (US$561,000).[348] Two fishermen died after their boat sank during the storm off the Ban Laem District while a third remains missing.[349]

Typhoon Krovanh

At the same time when Tropical Storm Vamco was named, another tropical disturbance was monitored by both the JMA and JTWC about 806 km (500 mi) east of Andersen Air Force Base.[350] The JTWC issued a TCFA on the system later that day.[351] On September 14, the JTWC upgraded the system to a tropical depression, designating it as 20W.[352] Due to an increase of deep convection near the center, both agencies upgraded 20W to Tropical storm Krovanh by the next day.[353][354] On September 16, Krovanh showed signs of increasing organization.[355] Based on this, the JMA upgraded Krovanh to a severe tropical storm.[356] Late on the same day, microwave imagery showed tightly curved bands wrapping into a well-defined microwave eye;[357] subsequently, both agencies upgraded Krovanh to typhoon status.[358][359] Embedded in an area of very favorable environment with wind shear diminishing,[360] the typhoon developed an eye and became more symmetrical. The JTWC estimates that Krovanh peaked with an intensity equal to that of a Category 3 typhoon.[361] The convective core started to struggle due to dry air over the western periphery and Krovanh moved in an area of increasing vertical windshear, resulting in a weakening trend.[362] On September 19, both the JMA and the JTWC downgraded Krovanh to a severe tropical storm.[363][364] On September 20, the center of Krovanh became fully exposed[365] and the JMA later downgraded Krovanh to a tropical storm.[366] Shortly thereafter, the JTWC issued their final warning.[367] The JMA later issued its final warning on Krovanh on September 21, as it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone.[368][369] The extratropical remnants of Krovanh lingered to the east of Japan for a few days with a cyclonic loop before turning to the northeast.[369]

Typhoon Dujuan (Jenny)

The JTWC identified a tropical disturbance on September 17 about 220 km (135 mi) east-southeast of Ujelang Atoll.[370] Late on September 21, gradual development occurred like persistent deep symmetric convection, and both the JMA and the JTWC upgraded the system to a tropical depression.[371][372] On September 22, wind shear caused the circulation to become displaced to the east from the deep convection.[373] Despite the wind shear, thunderstorm activity increased, prompting the JMA to upgrade the depression to a tropical storm.[374] The JTWC did the same early on September 23.[375] Dujuan entered the Philippine area of responsibility and was named Jenny.[376] On the next day, Dujuan entered a favorable environment and the JMA upgraded Dujuan to a severe tropical storm.[377][378] With tightly curved banding wrapping around the eye, both agencies assessed Dujuan's intensity at typhoon strength.[379][380] Following an improved and intense convective core structure with cooler cloud tops surrounding a large 38-nm wide eye.[381] Dujuan started to undergo explosive intensification.[382] On September 27, Dujuan rapidly reached peak intensity based on JTWC data, with winds of 240 km/h (150 mph). The typhoon became more symmetric, taking on annular characteristics, while featuring a large and well-defined eye.[383][384] With favorable environments aloft, evident by excellent radial outflow, deep convective banding and very low shear, Dujuan maintained its intensity.[385] However, on September 28, Dujuan's large symmetrical eye began to be cloud-filled as it interacted with the mountainous country of Taiwan, resulting in weakening[386] and then landfall over Nan'ao, Yilan.[387] Dujuan continued to weaken, and by the morning of September 29, the JTWC issued their final warning.[388] While making its second landfall over Xiuyu District, Putian of Fujian,[389] the JMA downgraded Dujuan to a severe tropical storm,[390] then a tropical storm later as it rapidly deteriorated over land.[391] It was last noted during September 30 inland over the Chinese province of Jiangxi.[392]

Typhoon Mujigae (Kabayan)

On September 28, a cluster of thunderstorms developed into a tropical disturbance near Palau. With more organization, the JMA classified the system as a tropical depression early on September 30.[393] On the next day, the PAGASA upgraded it to a tropical depression, assigning it the name Kabayan.[394] Later that day, the JTWC started following the storm.[395] All three agencies then classified Kabayan as a tropical storm, with the JMA naming it Mujigae.[396][397][398] By October 2, Mujigae made landfall over Aurora Province. After briefly weakening over land,[399] Mujigae reemerged into the South China Sea, where warm sea-surface temperatures favored development.[400] The JMA re-upped the intensity to severe tropical storm strength.[401] On the next day, an eye began to form, prompting the JMA and the JTWC to classify Mujigae as a typhoon.[402][403] Due to favorable conditions aloft, Mujigae explosively intensified into a Category 4-equaivlent typhoon (based on JTWc data) as cooling clouds tops surrounded the eye. At the same time, Mujigae made landfall over Zhanjiang and, according to the JTWC, briefly reached peak intensity with winds of 215 km/h (135 mph);[404] however, according to the JMA, the typhoon was not quite as intense.[405] A few hours later, the JTWC issued its final warning as Mujigae rapidly weakened over land.[406] Later in the same day, the JMA downgraded Mujigae to a severe tropical storm, then a tropical storm.[407][408] The JMA issued its final advisory on Mujigae as it further weakened to a tropical depression early on October 5.[409]

Severe Tropical Storm Choi-wan

On October 1, the JMA started to monitor a tropical depression near Wake Island.[410] By the next day, the system's circulation became expansive as the JMA upgraded the depression to a tropical storm, naming it Choi-wan.[411] The JTWC classified the system as a tropical storm by October 2, due to improved banding features, despite a large windfield.[412][413] Despite favorable conditions, Choi-wan maintained its intensity as a weak system due to a large and very broad circulation; mesovortices were seen on satellite imagery rotating cyclonically in its center.[414] On October 4, Choi-wan began to consolidate[415] and develop a ragged eye. Based on this, the JMA upgraded Choi-wan to a severe tropical storm.[416] On October 6, the JTWC upgraded the storm to a typhoon.[417] Later that day, Choi-wan reached its peak intensity of 130 km/h (80 mph) while exhibiting an elongated microwave eye feature.[418]

On October 7, Choi-wan started to slowly weaken in response to southwesterly shear that caused its eye to become cloud-filled.[419][420] Later that day, the JTWC issued its final warning as Choi-wan moved further northward with increasing and high vertical wind shear and was downgraded to high-end tropical storm intensity.[421] According to the JMA, with Choi-wan becoming extratropical early on October 8, they issued their final warning and stated that Choi-wan reached peak strength with a minimum pressure of 955 hPa still as a severe tropical storm, without reaching typhoon intensity.[422][423]

Typhoon Koppu (Lando)

On October 11, an area of convection persisted approximately 528 km (328 mi) north of Pohnpei.[424] Hours later, the JMA upgraded the system to a tropical depression.[425] The JTWC later followed suit on October 13.[426] Despite some shear, the depression developed rain bands and a central dense overcast.[427] Then, the JMA reported that the cyclone attained tropical storm intensity.[428][429] Koppu, while moving westward, initially showed a partially exposed circulation due to continued shear.[430] At around this time, PAGASA started issuing advisories on Koppu as it entered their area of responsibility and was named Lando.[431] On October 15, the JMA reported that Koppu reached typhoon status[432] as convection consolidated around an apparent microwave eye.[433] With SSTs over 31 °C over the Philippine Sea, intensification continued and on October 17, Koppu developed an eye and was raised by the JTWC to an intensity equal to a Category 3 hurricane,[434] Twelve hours later, both the JTWC and JMA estimated that Koppu reached peak intensity, with the JTWC upgrading it to a super typhoon.[435][436] Initially, the JTWC forecasted Koppu to reach Category 5 intensity, however the typhoon made landfall earlier than expected in the eastern Philippines.[437]

Typhoon Champi

During October 13, the JMA and the JTWC reported that a tropical depression developed northeast of Pohnpei State in the Marshall Islands.[438][439] During the early hours of October 14, the JMA and JTWC upgraded the depression into Tropical Storm Champi, despite limited convection.[438][440] Moving in a west-northwestward direction, Champi was steadily intensifying in a favorable environment aloft with cooling cloud tops.[441] While passing through the Mariana Islands, Champi was deemed as a severe tropical storm by the JMA.[438] Early on October 16, Champi intensified to a typhoon.[438][442] Following the formation of an eye,[443] surrounded by a deep convective core,[444] the typhoon began to steadily deepen as it moved in a northward direction.[445] Therefore, Champi reached peak intensity; according to the JTWC, the typhoon peaked at Category 4-equivalent typhoon intensity[446] while the JMA estimated peak winds of 165 km/h (105 mph) on October 18.[438] The next day, Champi started to weaken as the cyclone became increasingly asymmetric and dry air started to wrap into the storm's core.[447][448] Convection briefly increased on October 20,[449] but the re-intensification was short-lived as on October 22, Champi started to interact with strong mid-latitude westerly flow,[450] creating increased wind shear.[451] Convection rapidly decayed over Champi and the JMA downgraded it to a severe tropical storm.[438] Both the JTWC and the JMA issued their final advisory as Champi became extratropical on October 25.[438][452][453] The extratropical remnants crossed the basin on October 26, and fully dissipated on October 28 south of Alaska.[438]

Tropical Depression 26W

On October 20, the JMA started to monitor a tropical depression embedded within a moderately conducive environment aloft, about 400 km (250 mi) to the southwest of Wake Island.[454][455] The depression's low level circulation center was fully exposed, while isolated amounts of deep atmospheric convection flared over the systems southwestern quadrant.[455] Following an increase in convection of the center,[456] the JTWC subsequently initiated advisories on the system and classified it as Tropical Depression 26W during October 22, while it was located about 1,430 km (890 mi) to the east of Iwo To, Japan.[457] During that day the system interacted with the mid-latitude westerly flow and transitioned into an extra tropical cyclone, as it rounded the edge of a ridge.[458][459] During their post-analysis of the system, the JTWC determined that the system was a subtropical depression rather than a tropical depression.[460]

Typhoon In-fa (Marilyn)

During November 16, the JMA started to monitor a tropical depression, about 200 km (125 mi) southeast of Kosrae in the Federal States of Micronesia.[461] Moving north-westward within a favorable environment aloft,[462] the JTWC classified the system as a tropical depression early on November 17.[463] Twelve hours later, the JMA upgraded the depression to tropical storm intensity.[464] After developing a brief eye, the JTWC upgraded In-fa to a typhoon,[465] only to weaken back to a tropical storm hours later according to both agencies.[466][467] However, on November 20, the JTWC upgraded In-fa back to a typhoon and the JMA to a severe tropical storm after following an increase in organization.[461][468] After its eye became better organized and symmetric early on November 21, the JTWC classified In-fa as a Category 4-equivalent typhoon,[469] while the JMA reported that In-fa peaked in intensity, with winds of 175 km/h (110 mph).[461] Shortly after its peak, the eye of In-fa became less defined.[470] On November 22, Typhoon Infa entered PAGASA's warning zone, receiving the local name Marilyn.[471] In-fa became less organized[472] due to increased shear, In-fa started to turn northwards late on November 23.[473] The next day, In-fa further weakened to severe tropical storm strength, and to tropical storm strength on November 25.[461][474] During November 26, In-fa started to transition into an extratropical cyclone, before the system dissipated during the next day as it merged with a front.[461][475][476]

Typhoon Melor (Nona)

During December 10, the JMA started to monitor a tropical depression, that had developed about 665 km (415 mi) to the south of Guam.[477] By December 11, the JMA upgraded it to a tropical storm, naming it Melor,[478] while the JTWC and PAGASA started tracking the system, which was tracking west-northwestward along the southern periphery of a ridge, the latter naming it Nona.[479][480] Situated in favorable environment with low shear and warm SSTs, Melor intensified steadily.[481][482] On December 13, Melor attained typhoon intensity.[483] Following an episode of rapid intensification,[484] the JMA estimates that Melor peaked with winds of 175 km/h (110 mph).[477] However, later Melor made its first landfall over in Eastern Samar, which briefly caused weakening.[485] After meandering for several days, Melor emerged to the South China Sea on December 16, but continued weakening due to unfavorable conditions.[486] Data from the JMA suggests that Melor dissipated early on December 17.[487]

According to NDRRMC, a total of 42 people were killed and ₱6.46 billion (US$136 million) were total of infrastructure and agricultural damages caused by Melor (Nona).[488] Oriental Mindoro was placed under a state of calamity due to the devastation caused by the typhoon.[489] Pinamalayan in Oriental Mindoro was worst hit, with 15,000 homes destroyed, leaving 24,000 families in evacuation centers.[490] Due to the severe damage brought about by the typhoon in the provinces of Southern Luzon, Oriental Mindoro, and Visayas, Philippine President Benigno Aquino III declared a "State of National Calamity" in the country.[491]

Tropical Depression 29W (Onyok)

During December 13, a tropical disturbance developed within a favourable environment for further development, about 1,165 km (725 mi) to the southeast of Yap Island.[492] Over the next day the system gradually moved north-westwards and was classified as a tropical depression by the JMA.[493] With enough convection, the JTWC started to track the system with the designation of 29W.[494] Moving westwards, 29W entered the Philippine area of responsibility, with PAGASA naming it as Onyok.[495] Onyok reached its peak intensity on December 17, when flaring convection near its center had weakened and became exposed.[496] The system rapidly deteriorated when the JTWC issued its final advisory early the next day.[497] The system was last noted by the JMA during the next day, as it made landfall over Davao Oriental in Mindanao.[498][499] Infrastructural damage were at Php 1.1 million (US$23,300).[500]

Other systems

On January 1, Tropical Depression Jangmi (Seniang) from the previous season was active within the Sulu Sea to the north of Malaysia.[14] Over the next day the system moved southwards, before it made landfall on Malaysia and dissipated.[14] During January 2, a tropical depression developed to the northwest of Brunei, within an area that was marginally favorable for further development.[501][502] Over the next day the system moved into an area of moderate vertical wind shear, with atmospheric convection becoming displaced to the west of the fully exposed low level circulation center.[503] The system was subsequently last noted by the JMA during January 4, as it dissipated in the South China Sea near the Malaysian-Indonesian border.[504][505][506]

During July 1, a tropical depression developed, about 700 km (435 mi) to the southeast of Hagåtña, Guam.[22] Over the next day the system remained near stationary, before it dissipated during July 2.[22] On July 14, the JMA started to monitor a weak tropical depression several kilometers east-northeast of the Philippines.[507] The system showed intensification; however, the JMA issued its final warning on the system shortly thereafter.[508] On July 15, the JMA re-initiated advisories on the depression.[509] The depression moved in a northward direction as it was absorbed by the outflow of Typhoon Nangka the next day.[510] Another tropical depression developed on July 18 and dissipated near Japan and south of the Korean Peninsula on July 20.[511][512] During July 20, the JMA briefly monitored a tropical depression that had developed over the Chinese province of Guangdong.[512][513] During August 26, the remnants of Hurricane Loke moved into the basin from the Central Pacific and were immediately classified as an extra-tropical cyclone.[514]

During October 6, the remnants of Tropical Depression 08C moved into the basin from the Central Pacific and were classified as a tropical depression by the JMA.[515] The system drifted slowly in a westward direction until it started deteriorating,[516] and the JMA downgraded the depression to a low-pressure area late on October 7.[517] Its remnants continued moving westward which became Tropical Storm Koppu. During October 19, the JMA started to monitor a tropical depression that had developed, about 375 km (235 mi) to the south-west of Wake Island.[518] The system was located within a marginal environment for further development, with moderate vertical wind shear and weak convergence preventing atmospheric convection from developing over the depression.[519] Over the next couple of days the system moved and near the subsidence side of Typhoon Champi, before it was last noted by the JMA on October 22.[520][521] The final tropical depression of the system developed on December 20 north of Malaysia.[522] The system moved in a slow westward direction for a few days until it was last monitored on December 23, ending the season.[523][524]

Storm names

Summarize

Perspective

Within the Northwest Pacific Ocean, both the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) and the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) assign names to tropical cyclones that develop in the Western Pacific, which can result in a tropical cyclone having two names.[525] The Japan Meteorological Agency's RSMC Tokyo — Typhoon Center assigns international names to tropical cyclones on behalf of the World Meteorological Organization's Typhoon Committee, should they be judged to have 10-minute sustained windspeeds of 65 km/h (40 mph).[526] PAGASA names to tropical cyclones which move into or form as a tropical depression in their area of responsibility located between 135°E and 115°E and between 5°N and 25°N even if the cyclone has had an international name assigned to it.[525] The names of significant tropical cyclones are retired, by both PAGASA and the Typhoon Committee.[526] Should the list of names for the Philippine region be exhausted then names will be taken from an auxiliary list of which the first ten are published each season. Unused names are marked in gray.

International names

During the season 27 tropical storms developed in the Western Pacific and 25 were named by the JMA, when the system was judged to have 10-minute sustained windspeeds of 65 km/h (40 mph).[527] The JMA selected the names from a list of 140 names, that had been developed by the 14 members nations and territories of the ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee.[528] During the season the names Atsani, Champi and In-fa were used for the first time, after they had replaced the names Morakot, Ketsana and Parma, which were retired after the 2009 season.[528]

| Mekkhala | Higos | Bavi | Maysak | Haishen | Noul | Dolphin | Kujira | Chan-hom | Linfa | Nangka | Soudelor | Molave |

| Goni | Atsani | Etau | Vamco | Krovanh | Dujuan | Mujigae | Choi-wan | Koppu | Champi | In-fa | Melor |

|

Retirement

After the season the Typhoon Committee retired the names Soudelor, Mujigae, Koppu and Melor from the naming lists, and in February 2017, the names were subsequently replaced with Saudel, Surigae, Koguma and Cempaka for future seasons, respectively.[529]

Philippines

| Amang | Betty | Chedeng | Dodong | Egay |

| Falcon | Goring | Hanna | Ineng | Jenny |

| Kabayan | Lando | Marilyn | Nona | Onyok |

| Perla (unused) | Quiel (unused) | Ramon (unused) | Sarah (unused) | Tisoy (unused) |

| Ursula (unused) | Viring (unused) | Weng (unused) | Yoyoy (unused) | Zigzag (unused) |

| Auxiliary list | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abe (unused) | Berto (unused) | Charo (unused) | Dado (unused) | Estoy (unused) |

| Felion (unused) | Gening (unused) | Herman (unused) | Irma (unused) | Jaime (unused) |

During the season PAGASA used its own naming scheme for the 15 tropical cyclones, that either developed within or moved into their self-defined area of responsibility.[530][531] This is the same list used during the 2011 season, except for the names Betty, Jenny, Marilyn, Perla, and Sarah, which replaced Bebeng, Juaning, Mina, Pedring, and Sendong, respectively. Storms were named Betty, Jenny, Marilyn, and Nona for the first (and only, in case of Nona) time this year.[530]

While the name Nonoy was originally included on the list, it was changed to Nona as it bears similarity to the term "Noynoy", the incumbent president's nickname at that time.[532][533]

Retirement

After the season, PAGASA removed the names Lando and Nona from their naming lists, as they had caused over ₱1 billion in damages during their onslaught in the country.[534] They were subsequently replaced on the list with the names of Liwayway and Nimfa for the 2019 season.[534]

Season effects

Summarize

Perspective

This table summarizes all the systems that developed within or moved into the North Pacific Ocean, to the west of the International Date Line during 2015. The tables also provide an overview of a systems intensity, duration, land areas affected and any deaths or damages associated with the system.

| Name | Dates | Peak intensity | Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Wind speed | Pressure | ||||||

| TD | January 2–4 | Tropical depression | Not specified | 1,006 hPa (29.71 inHg) | Borneo | None | None | |

| Mekkhala (Amang) | January 13–21 | Severe tropical storm | 110 km/h (68 mph) | 975 hPa (28.79 inHg) | Yap State, Philippines | $8.92 million | 3 | [47][535] |

| Higos | February 6–12 | Very strong typhoon | 165 km/h (103 mph) | 940 hPa (27.76 inHg) | None | None | None | |

| Bavi (Betty) | March 10–21 | Tropical storm | 85 km/h (53 mph) | 990 hPa (29.23 inHg) | Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Mariana Islands, Philippines | $2.25 million | 9 | [64][67] |

| Maysak (Chedeng) | March 26 – April 7 | Violent typhoon | 195 km/h (121 mph) | 910 hPa (26.87 inHg) | Micronesia, Philippines | $8.5 million | 4 | |

| Haishen | April 2–6 | Tropical storm | 65 km/h (40 mph) | 998 hPa (29.47 inHg) | Caroline Islands | $200,000 | None | [88] |

| Noul (Dodong) | May 2–12 | Violent typhoon | 205 km/h (127 mph) | 920 hPa (27.17 inHg) | Caroline Islands, Taiwan Philippines, Japan | $23.8 million | 2 | [536] |

| Dolphin | May 6–20 | Very strong typhoon | 185 km/h (115 mph) | 925 hPa (27.32 inHg) | Caroline Islands, Mariana Islands, Kamchatka Peninsula, Alaska | $13.5 million | 1 | [537] |

| Kujira | June 19–25 | Tropical storm | 85 km/h (53 mph) | 985 hPa (29.09 inHg) | Vietnam, China | $16 million | 9 | [122][124][538] |

| Chan-hom (Falcon) | June 29 – July 13 | Very strong typhoon | 165 km/h (103 mph) | 935 hPa (27.61 inHg) | Mariana Islands, Taiwan, China, Korean Peninsula, Russian Far East | $1.58 billion | 18 | [539] |

| TD | July 1–2 | Tropical depression | Not specified | 1,000 hPa (29.53 inHg) | Caroline Islands | None | None | |

| Linfa (Egay) | July 1–10 | Severe tropical storm | 95 km/h (59 mph) | 980 hPa (28.94 inHg) | Philippines, Taiwan, China, Vietnam | $285 million | 1 | [172][540] |

| Nangka | July 2–18 | Very strong typhoon | 185 km/h (115 mph) | 925 hPa (27.32 inHg) | Marshall Islands, Caroline Islands, Mariana Islands, Japan | $209 million | 2 | [citation needed] |

| Halola (Goring) | July 13–26 | Strong typhoon | 150 km/h (93 mph) | 955 hPa (28.20 inHg) | Wake Island, Japan, Korean Peninsula | $1.24 million | None | [541] |

| TD | July 14 | Tropical depression | Not specified | 1,000 hPa (29.53 inHg) | None | None | None | |

| TD | July 15–16 | Tropical depression | Not specified | 1,000 hPa (29.53 inHg) | None | None | None | |

| TD | July 18–20 | Tropical depression | Not specified | 1,004 hPa (29.65 inHg) | Japan | None | None | |

| TD | July 20–21 | Tropical depression | Not specified | 1,000 hPa (29.53 inHg) | China | None | None | |

| 12W | July 22–25 | Tropical depression | 65 km/h (40 mph)[P 1] | 1,008 hPa (29.77 inHg) | Philippines | None | None | |

| Soudelor (Hanna) | July 29 – August 11 | Violent typhoon | 215 km/h (134 mph) | 900 hPa (26.58 inHg) | Mariana Islands, Philippines Taiwan, Ryukyu Islands, China, Korean Peninsula, Japan | $4.09 billion | 59 | [238][542] [543][544][545] |

| 14W | August 1–5 | Tropical depression | Not specified | 1,008 hPa (29.77 inHg) | Japan | None | None | |

| Molave | August 6–14 | Tropical storm | 85 km/h (53 mph) | 985 hPa (29.09 inHg) | None | None | None | |

| Goni (Ineng) | August 13–25 | Very strong typhoon | 185 km/h (115 mph) | 930 hPa (27.46 inHg) | Mariana Islands, Philippines, Taiwan, Japan, Korean Peninsula, China, Russian Far East | $1.05 billion | 74 | [546][547] |