San Quentin Rehabilitation Center

Men's prison in California, US From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Men's prison in California, US From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

San Quentin Rehabilitation Center (SQ), formerly known as San Quentin State Prison,[2] is a California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation state prison for men, located north of San Francisco in the unincorporated[3] place of San Quentin in Marin County.

| |

| Location | San Quentin, California, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37.939°N 122.489°W |

| Status | Operational |

| Security class | Minimum–maximum |

| Capacity | 3,084 |

| Population | 3,542 (114.9%) (as of January 31, 2023[1]) |

| Opened | July 1852 |

| Managed by | California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation |

| Warden | Chance Andes |

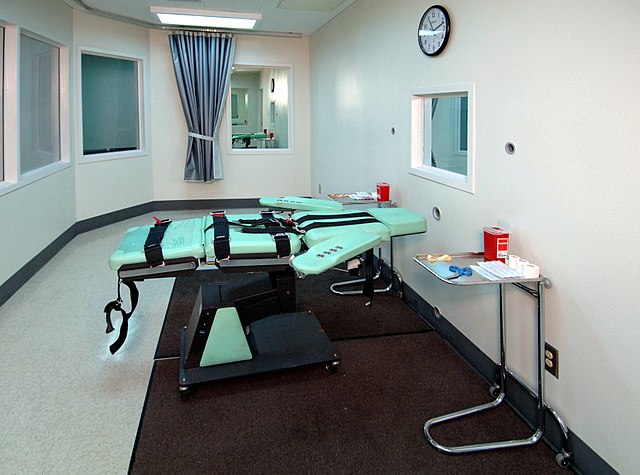

Established in 1852, and opening in 1854,[4] San Quentin is the oldest prison in California. The state's only death row for male inmates, the largest in the United States, was located at the prison.[5][6][7] Its gas chamber has not been used since 1993, and its lethal injection chamber was last used in 2006.[8] The prison has been featured on film, radio drama, video, podcast, and television; is the subject of many books; has hosted concerts; and has housed many notorious inmates.

The correctional complex sits on Point San Quentin, which consists of 432 acres (1.75 square kilometers) on the north side of San Francisco Bay.[9][10][11][12] The prison complex itself occupies 275 acres (1.11 km2), valued in a 2001 study at between $129 million and $664 million.[13]

As of July 31, 2022, San Quentin was incarcerating people at 105% of its design capacity, with 3,239 occupants.[14]

Men condemned to death in California were, in general, formerly held at San Quentin. Most of the former death row population, with some exceptions, have been moved to general population in other California institutions as of May 28, 2024. These transfers have been arranged to comply with Proposition 66 and are being managed by the Condemned Inmate Transfer Program of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Of the 620 condemned inmates in California as of October 8, 2024, only 16 remained at San Quentin, with the last 16 inmates expected to also be transferred after completing needed medical or psychiatric care. Despite the transfers, the condemned inmates remain under sentence of death at their new institutions.[7]

Condemned women are held at Central California Women's Facility in Chowchilla.[15] As of December 2015, San Quentin held almost 700 male inmates in its Condemned Unit, or "death row."[16] As of 2001, San Quentin's death row was described as "the largest in the Western Hemisphere";[17] as of 2005, it was called "the most populous execution antechamber in the United States."[6] The states of Florida and Texas had fewer death row inmates in 2008 (397 and 451 respectively) than San Quentin.[18]

The death row at San Quentin was divided into three sections: the quiet "North-Segregation" or "North-Seg," built in 1934, for prisoners who "don't cause trouble"; the "East Block," a "crumbling, leaky maze of a place built in 1927"; and the "Adjustment Center" for the "worst of the worst."[6] Most of the prison's death row inmates resided in the East Block. The fourth floor of the North Block was the prison's first death row facility, but additional death row space opened after executions resumed in the U.S. in 1978. The adjustment center received solid doors, preventing "gunning-down" or attacking persons with bodily waste. As of 2016[update] it housed 81 death row inmates and four non-death row inmates.[19] A dedicated psychiatric facility serves the prisoners. A converted shower bay in the East Block hosted religious services. Many prison programs available for most inmates were unavailable for death row inmates.[16]

Although $395 million was allocated in the 2008–2009 state budget for new death row facilities at San Quentin, in December 2008 two legislators introduced bills to eliminate the funding.[20] The state had planned to build a new death row facility, but Governor Jerry Brown canceled those plans in 2011.[21] In 2015 Brown asked the Legislature for funds for a new death row as the current death row facilities were becoming filled. At the time the non-death row prison population was decreasing, opening room for death row inmates. As of 2015[update] the San Quentin death row had a capacity of 715 prisoners.[22]

All executions in California (male and female) take place at San Quentin.[15] The execution chamber is located in a one-story addition close to the East Block.[19] Women executed in California are transported to San Quentin by bus before being executed.[23]

The methods for execution at San Quentin have changed over time. Prior to 1893, the counties executed convicts. Between 1893 and 1937, 215 people were executed at San Quentin by hanging, after which 196 prisoners died in the gas chamber.[6] In 1995, the use of gas for execution was ruled "cruel and unusual punishment", which led to executions inside the gas chamber by lethal injection.[6] Between 1996 and 2006, eleven people were executed at San Quentin by lethal injection.[24]

In April 2007, staff of the California Legislative Analyst's Office discovered that a new execution chamber was being built at San Quentin; legislators subsequently "accuse[d] the governor of hiding the project from the Legislature and the public."[25] The old lethal injection facility had included an injection room of 43 square feet (4.0 square meters) and a single viewing area; the facility that was being built included an injection chamber of 230 square feet (21 m2) and three viewing areas for family, victim, and press.[26] Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger stopped construction of the facility the next week.[27] The legislature later approved $180,000 to finish the project, and the facility was completed.[28][29]

In addition to state executions, three federal executions have been carried out at San Quentin.[30] Samuel Richard Shockley and Miran Edgar Thompson had been incarcerated at Alcatraz Island federal penitentiary and were executed on December 3, 1948, for the murder of two prison guards during the Battle of Alcatraz.[31] Carlos Romero Ochoa had murdered a federal immigration officer after he was caught smuggling illegal immigrants across the border near El Centro, California. He was executed at San Quentin's gas chamber on December 10, 1948.[31]

On March 13, 2019, after Governor Gavin Newsom ordered a moratorium on the state's death penalty, the state withdrew its current lethal injection protocol, and San Quentin dismantled and indefinitely closed its gas and lethal injection execution chambers.[32]

Though numerous towns and localities in the area are named after Roman Catholic saints, and "San Quintín" is Spanish for "Saint Quentin", the prison was not named after the saint. The land on which it is situated, Point Quentin, is named after a Coast Miwok warrior named Quentín, fighting under Chief Marin, who was taken prisoner at that place.[53][54]

In 1851, California's first prison opened; it was a 268-ton wooden ship named the Waban, anchored in San Francisco Bay and outfitted to hold 30 inmates.[55][56] Some of the Waban's timber remains a part of the new hospital structure inside the prison. After a series of speculative land transactions and a legislative scandal,[57] inmates who were housed on the Waban constructed San Quentin which opened its first cell block, nicknamed "the Stones," in 1854. Before being retired altogether, this initial unit would come to be used as a dungeon after newer additions were constructed atop it. The Stones, however, survive to this day and is thought to be California's oldest surviving public work.[58]

Clinton Duffy was the warden from 1940 to 1952. He had fresh insights informing the reorganization of the prison structure and reformation of prison management. Prior to Duffy, San Quentin had gone through years of violence, inhumane punishments and civil rights abuses against prisoners. The previous warden was forced to resign.[59] Duffy had the offending prison guards fired and added a librarian, psychiatrists, and several surgeons at San Quentin. Duffy's press agent publicized sweeping reforms. San Quentin remained a brutal prison where prisoners continued to be beaten to death.[60] The use of torture as an approved method of interrogation at San Quentin was banned in 1944.[61]

In 1941, the first prison meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous took place at San Quentin; in commemoration of this, the 25-millionth copy of the AA Big Book was presented to Jill Brown, of San Quentin, at the International Convention of Alcoholics Anonymous in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.[62]

In 1947, Warden Duffy recruited Herman Spector to work as assistant warden at San Quentin. Spector turned down the invitation to be assistant warden and chose instead to become senior librarian if he could institute his theories on reading as a program to encourage pro-social behavior. By 1955, Spector was being interviewed in library journals and suggesting the prison library could contribute significantly to rehabilitation.[63]

The dining hall of the prison is adorned by six 20 ft (6.1 m) sepia-toned murals depicting California history. They were painted by Alfredo Santos, one-time convicted heroin dealer and successful artist, during his 1953–1955 incarceration.[64][65] The murals were painted with a thinned, raw sienna oil paint directly to plaster as he was denied use of other colors to paint with.[66]

Between 1992 and 1997, a "boot camp" was held at the prison that was intended to "rehabilitat[e] first-time, nonviolent offenders"; the program was discontinued because it did not reduce recidivism or save money.[67]

A 2005 court-ordered report found that the prison was "old, antiquated, dirty, poorly staffed, poorly maintained with inadequate medical space and equipment and overcrowded."[68] Later that year, the warden was fired for "threaten[ing] disciplinary action against a doctor who spoke with attorneys about problems with health care delivery at the prison."[69] By 2007, a new trauma center had opened at the prison and a new $175 million medical complex was planned.[70]

In 2020, the prison became the center of a COVID-19 outbreak, after a group of prisoners were transferred to San Quentin from the California Institution for Men in Chino, California. Initial reports suggested that San Quentin officials were told that the new inmates had all tested negative; however, few had been tested at all. By June 22, at least 350 inmates and staff had tested positive, in what a federal judge called a "significant failure" of policy.[71]

In March 2023, California Governor Gavin Newsom announced a "historic transformation" of the then-called San Quentin State Prison as part of a project to improve public safety through a greater focus on rehabilitation and education.[72] As part of the project, the prison was renamed San Quentin Rehabilitation Center and an advisory group of rehabilitation and public safety experts was formed to advise the efforts.

In 2020, 12 death row inmates at San Quentin died in the span of less than two months after a COVID-19 outbreak. All of the inmates were hospitalized before their deaths.[161]

Gang-pulp author Margie Harris wrote a story on San Quentin for the short-lived pulp magazine Prison Stories. The story, titled "Big House Boomerang," appeared in the March 1931 issue. It used San Quentin's brutal jute mill as its setting. Harris' knowledge of the prison came from her days as a newspaper reporter in the Bay Area, and her acquaintance with famous San Quentin prisoner Ed Morrell.[222]

The 1915 novel The Star Rover by Jack London was based in San Quentin. A framing story is told in the first person by Darrell Standing, a university professor serving life imprisonment in San Quentin State Prison for murder. Prison officials try to break his spirit by means of a torture device called "the jacket," a canvas jacket which can be tightly laced so as to compress the whole body, inducing angina. Standing discovers how to withstand the torture by entering a kind of trance state, in which he walks among the stars and experiences portions of past lives.

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.