Sahitya Akademi Award

Literary honour awarded to authors of outstanding literary works in India From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

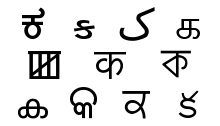

The Sahitya Akademi Award is a literary honour in India, which the Sahitya Akademi, India's National Academy of Letters, annually confers on writers of the most outstanding books of literary merit published in any of the 22 languages of the 8th Schedule to the Indian constitution as well as in English and Rajasthani language.[1][2]

| Sahitya Akademi Award | |

|---|---|

| Award for individual contributions to Literature | |

| |

| Awarded for | Literary award in India |

| Sponsored by | Sahitya Akademi, Government of India |

| First award | 1954 |

| Final award | 2024 |

| Highlights | |

| Total awarded | 21 (2024) |

| Website | sahitya-akademi.gov.in |

Established in 1954, the award comprises a plaque and a cash prize of ₹ 1,00,000.[3] The award's purpose is to recognise and promote excellence in Indian writing and also acknowledge new trends. The annual process of selecting awardees runs for the preceding twelve months. The plaque awarded by the Sahitya Akademi was designed by the Indian film-maker Satyajit Ray.[4] Prior to this, the plaque occasionally was made of marble, but this practice was discontinued because of the excessive weight. During the Indo-Pakistan War of 1965, the plaque was substituted with national savings bonds.[5]

Recipients

Lists of Sahitya Akademi Award winners cover winners of the Sahitya Akademi Award, a literary honor in India which Sahitya Akademi, India's National Academy of Letters, annually confers on writers of outstanding works in one of the twenty-four major Indian languages.[6] The lists are organized by language.

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Assamese

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Bengali

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Bodo

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Dogri

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for English

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Gujarati

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Hindi

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Kannada

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Kashmiri

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Konkani

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Maithili

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Malayalam

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Meitei

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Marathi

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Nepali

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Odia

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Punjabi

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Rajasthani

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Sanskrit

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Santali

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Sindhi

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Tamil

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Telugu

- List of Sahitya Akademi Award winners for Urdu

Other literary honors

Summarize

Perspective

Sahitya Akademi Fellowships

They form the highest honor which the Akademi confers through a system of electing Fellows and Honorary Fellows. (Sahitya Akademi Award is the second-highest literary honor next to a Sahitya Akademi Fellowship).

Bhasha Samman

Sahitya Akademy gives these special awards to writers for significant contribution to Indian languages other than the above 24 major ones and also for contributions to classical and medieval literature. Like the Sahitya Akademi Awards, Bhasha Samman too comprise a plaque and a cash prize of ₹1,00,000 (from 2009). The Sahitya Akademi instituted the Bhasha Samman in 1996 to be given to writers, scholars, editors, collectors, performers or translators who have made considerable contribution to the propagation, modernization or enrichment of the languages concerned. The Samman carries a plaque along with an amount equal to its awards for creative literature i.e. ₹1,00,000. It was ₹25,000 at the time of inception, increased to ₹40,000 from 2001, ₹50,000 from 2003 and to ₹1,00,000 from 2009. The Sammans are given to 3-4 persons every year in different languages on the basis of recommendations of experts' committees constituted for the purpose.

The first Bhasha Sammans were awarded in to Dharikshan Mishra for Bhojpuri, Bansi Ram Sharma and M.R. Thakur for Pahari (Himachali), K. Jathappa Rai and Mandara Keshava Bhat for Tulu and Chandra Kanta Mura Singh for Kokborok, for their contribution to the development of their respective languages.

Sahitya Akademi Prize for Translation

Awards for translations were instituted in 1989 at the insistence of then-Prime Minister of India, P. V. Narasimha Rao.[7] The Sahitya Akademi annually gives these awards for outstanding translations of major works in other languages into one of the 24 major Indian languages. The awards comprise a plaque and a cash prize of ₹50,0000. The initial proposal for translation prizes contained provisions for a prize for translations into each of the twenty-two languages recognised by the Akademi; however, this was soon found to be unviable for several reasons: the Akademi found that there were insufficient entries in all the languages, and there were difficulties in locating experts knowledgeable in both, the language of translation and the original language, to judge the translations.[7] Consequently, the Board decided to dispense with its original requirement for additional expert committees to evaluate the translations and also ruled that it was not obligated to grant prizes in languages where suitable books were not nominated.[7] The Akademi also requires that both, the original author as well as the translator, are to be Indian nationals.[7]

Over time, the Akademi has modified and expanded the conditions for the Translation Prizes. In 1982, the Akademi began to allow translations made in link languages to be eligible for the Awards, although it noted that translations made directly from the original language would always be preferred.[7] In 1985, the Akademi also held that joint translations would be eligible, and in 1997, it dispensed with the process of advertising for nominations and replaced it with invitations for recommendations from advisory boards and Committee members.[7] As of 2006, 268 prizes have been awarded to 256 translators.[7]

Yuva Puraskar

Golden Jubilee Awards

On the occasion of its Golden Jubilee, Sahitya Akademi awarded the following prizes for outstanding works of poetry in translation from Indian languages.

- Rana Nayar for his translation of the verses of the Sikh saint Baba Farid from Punjabi.

- Tapan Kumar Pradhan for English translation of his own Odia poem collection Kalahandi

- Paromita Das for English translation of Parvati Prasad Baruwa's poems in Assamese.[citation needed][8]

The Golden Jubilee Prizes for Life Time Achievement and young achievers were awarded to Namdeo Dhasal, Ranjit Hoskote, Mandakranta Sen, Abdul Rasheed, Sithara S. and Neelakshi Singh.

Ananda Coomarswamy Fellowships

Named after the Ceylon Tamil writer Ananda Coomaraswamy, the fellowship was started in 1996. It is given to scholars from Asian countries to spend three to twelve months in India to pursue a literary project.

Premchand Fellowships

Named after Hindi and Urdu writer Premchand, the fellowship was started in 2005. It is given to persons of eminence in the field of Culture from SAARC countries. Notable awardees include Intizar Hussain, Selina Hossain, Yasmine Gooneratne, Jean Arasanayagam and Kishwar Naheed.[9]

Returns and Declines of Sahitya Akademi Awards

Summarize

Perspective

The Akademi has seen several instances of Awards being returned or declined as an act of protest.

1950s–1980s

In 1973, G.A. Kulkarni returned the Award for his collection of short stories in Marathi, Kajal Maya, because a controversy had arisen regarding the date of publication of the book and its consequent eligibility for the Award.[10] In 1969, Swami Anand declined the Award for contributions to Gujarati literature on the grounds that his religious beliefs precluded him from accepting any pecuniary benefits for public services.[10]

In 1981, Telugu writer V. R. Narla was given the Sahitya Akademi Award for his play, Sita Josyam, but returned it on the grounds that the Akademi had allowed an adverse review of the play to be published in their journal, Indian Literature.[11] In 1982, Deshbandhu Dogra Natan was given the Sahitya Akademi award for his Dogri novel, Qaidi ('Prisoner') but returned it on the grounds that he should have received the Award much earlier.[11] In 1983, Gujarati writer Suresh Joshi also returned the Award on the grounds that his book, Chintayami Manasa, did not, in his opinion, deserve the Award, and also expressed the opinion that the Award was generally granted to authors who were "spent forces".[11] This provoked a response from the then-President of the Akademi, Vinayaka Krishna Gokak, who said, concerning the awards that, "It is not possible to generalise on the basis of age. Nor can we expect the Akademi panels to be on the watch for a literary force on the upward curve and catch it at the moment before it starts going downwards. Panels change from year to year and they have to select not literary men but literary works which are adjudged to be the best among the publications of a particular period."[12]

1990s

In 1998, Gujarati writer Jayant Kothari also declined the Sahitya Akademi Award on the grounds that he had made a religious vow that precluded his acceptance of any competitive award, prize or position.[10] In 1991, Jagannatha Prasad Das, who was given the Award for his poetry in Odia declined for 'personal reasons'.[10] In 1996, T. Padmanabhan, who was given the Award for a book of short stories in Malayalam, declined on the grounds that the Akademi had not shown interest in supporting the short story form, although he noted that he was grateful to the Akademi for the honour.[10]

2000s

As of 2015[update], the award has been returned by many writers for various reasons. 38 recipients had announced their returning of the award in protest of the "rising intolerance in India" under the Modi government as also the murder of author M M Kalburgi and the Dadri lynching incident.[13][14] Among others, Ajmer Aulakh, Aman Sethi, Ganesh Devy, Kum Veerabhadrappa and Shashi Deshpande have publicly announced their return of the award.[15] To show their condemnation Deshpande, K Satchidanandan, PK Parakkadvu and Aravind Malagatti have also resigned their posts at the Sahitya Akademi institution.[14]

The recipients who announced to return the awards include: Ajmer Singh Aulakh (Punjabi),[16] Ambika Dutt (Hindi),[17] Anil R. Joshi (Gujarati),[18] Ashok Vajpeyi (Hindi),[19] Atamjit Singh (Punjabi),[16] Baldev Singh Sadaknama (Punjabi),[20] Bhoopal Reddy (Telugu),[21] Chaman Lal (Hindi),[22] Darshan Buttar (Punjabi),[23] Ganesh Devy (Gujarati/English),[24] Ghulam Nabi Khayal (Kashmiri),[25] GN Ranganatha Rao (Kannada),[26] Gurbachan Singh Bhullar (Punjabi),[27] Homen Borgohain (Assamese)[28] Jaswinder Singh (Punjabi),[20] K. Katyayani Vidhmahe (Telugu),[17] Kashi Nath Singh (Hindi),[29] Keki N. Daruwalla (English),[30] Krishna Sobti (Hindi),[17] Kumbar Veerabhadrappa (Kannada),[31] Mandakranta Sen (Bengali),[32] Manglesh Dabral (Hindi),[33] Marghoob Banihali (Kashmiri),[17] Mohan Bhandari (Punjabi),[17] Munawwar Rana (Urdu),[34] Nand Bhardwaj (Rajasthani),[35] Nayantara Sahgal (English),[36] Nirupama Borgohain (Assamese),[17] Rahman Abbas (Urdu),[37] Rahamat Tarikere (Kannada),[38] Rajesh Joshi (Hindi),[39] Sarah Joseph (Malayalam),[40] Srinath DN (Kannada),[41] Surjit Patar (Punjabi),[42] Uday Prakash (Hindi),[43][33] and Waryam Singh Sandhu (Punjabi).[16]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.