Der Spiegel

German weekly news magazine based in Hamburg From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Der Spiegel (German pronunciation: [deːɐ̯ ˈʃpiːɡl̩], lit. 'The Mirror', stylized in all caps) is a German weekly news magazine published in Hamburg.[1] With a weekly circulation of about 724,000 copies in 2022,[2] it is one of the largest such publications in Europe.[3] It was founded in 1947[4][3] by John Seymour Chaloner, a British army officer, and Rudolf Augstein, a former Wehrmacht radio operator who was recognized in 2000 by the International Press Institute as one of the fifty World Press Freedom Heroes.[5]

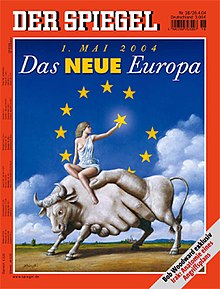

1 May 2004 issue | |

| Editor-in-Chief | Steffen Klusmann |

|---|---|

| Categories | News magazine |

| Frequency | Weekly (on Saturdays) |

| Circulation | 695,910/ week |

| Publisher | Spiegel-Verlag |

| Founder | Rudolf Augstein & John Seymour Chaloner |

| First issue | 4 January 1947 |

| Country | Germany |

| Based in | Hamburg |

| Language | German |

| Website | spiegel |

| ISSN | 0038-7452 (print) 2195-1349 (web) |

Der Spiegel is known in German-speaking countries mostly for its investigative journalism. It has played a key role in uncovering many political scandals such as the Spiegel affair in 1962 and the Flick affair in the 1980s. The news website by the same name was launched in 1994 under the name Spiegel Online with an independent editorial staff. Today, the content is created by a shared editorial team and the website uses the same media brand as the printed magazine.

History

Summarize

Perspective

Old Spiegel headquarters, Hamburg (1969–2011)

The first edition of Der Spiegel was published in Hanover on Saturday, 4 January 1947.[6] Its release was initiated and sponsored by the British occupational administration and preceded by a magazine titled Diese Woche (German: This Week),[6] which had first been published in November 1946.[3] After disagreements with the British, the magazine was handed over to Rudolf Augstein as chief editor, and was renamed Der Spiegel. From the first edition in January 1947, Augstein held the position of editor-in-chief, which he retained until his death on 7 November 2002.

After 1950, the magazine was owned by Rudolf Augstein and John Jahr;[7] Jahr's share merged with Richard Gruner's in 1965 to form the publishing company Gruner + Jahr. In 1969, Augstein bought out Gruner + Jahr for DM 42 million and became the sole owner of Der Spiegel. In 1971, Gruner + Jahr bought back a 25% share in the magazine. In 1974, Augstein restructured the company to make the employees shareholders. All employees with more than three years seniority were offered the opportunity to become an associate and participate in the management of the company, as well as in the profits.[citation needed] Since 1952, Der Spiegel has been headquartered in its own building in the old town part of Hamburg.[8]

Der Spiegel's circulation rose quickly. From 15,000 copies in 1947, it grew to 65,000 in 1948 and 437,000 in 1961. It was nearly 500,000 copies in 1962.[9] By the 1970s, it had reached a plateau at about 900,000 copies. When the German reunification in 1990 made it available to a new readership in former East Germany, the circulation exceeded one million.

The magazine's influence is based on two pillars; firstly the moral authority established by investigative journalism since the early years and proven alive by several scoops during the 1980s; secondly the economic power of the prolific Spiegel publishing house. Since 1988, it has produced the TV program Spiegel TV, and further diversified during the 1990s.

During the second quarter of 1992 the circulation of Der Spiegel was 1.1 million copies.[10] In 1994, Spiegel Online was launched.[11][12] It had separate and independent editorial staff from Der Spiegel. In 1999, the circulation of Der Spiegel was 1,061,000 copies.[13]

Der Spiegel had an average circulation of 1,076,000 copies in 2003.[14] In 2007 the magazine started a new regional supplement in Switzerland.[15] A 50-page study of Switzerland, it was the first regional supplement of the magazine.[15]

In 2010 Der Spiegel was employing the equivalent of 80 full-time fact checkers, which the Columbia Journalism Review called "most likely the world's largest fact checking operation".[16] The same year it was the third best-selling general interest magazine in Europe with a circulation of 1,016,373 copies.[17]

In 2018, Der Spiegel became involved in a journalistic scandal after it discovered and made public that one of its leading reporters, Claas Relotius, had "falsified his articles on a grand scale".[18][19]

Reception

When Stefan Aust took over in 1994, the magazine's readers realized that his personality was different from his predecessor. In 2005, a documentary by Stephan Lamby quoted him as follows: "We stand at a very big cannon!"[20] Politicians of all stripes who had to deal with the magazine's attention often voiced their disaffection for it. The outspoken conservative Franz Josef Strauss contended that Der Spiegel was "the Gestapo of our time". He referred to journalists in general as "rats".[21] The Social Democrat Willy Brandt called it "Scheißblatt" (i.e., a "shit paper") during his term in office as Chancellor.[22]

Der Spiegel often produces feature-length articles on problems affecting Germany (like demographic trends, the federal system's gridlock or the issues of its education system) and describes optional strategies and their risks in depth.[23][24][25][26][27] The magazine plays the role of opinion leader in the German press.[28] According to The Economist, Der Spiegel is one of continental Europe's most influential magazines.[29]

Investigative journalism

Summarize

Perspective

Der Spiegel has a distinctive reputation for revealing political misconduct and scandals. Online Encyclopædia Britannica emphasizes this quality of the magazine as follows: "The magazine is renowned for its aggressive, vigorous, and well-written exposés of government malpractice and scandals."[3][11] It merited recognition for this as early as 1950 when the federal parliament launched an inquiry into Spiegel's accusations that bribed members of parliament had promoted Bonn over Frankfurt as the seat of West Germany's government.

During the Spiegel scandal in 1962, which followed the release of a report about the possible low state of readiness of the German armed forces, minister of defense and conservative figurehead Franz Josef Strauss had Der Spiegel investigated. In the course of this investigation, the editorial offices were raided by police while Rudolf Augstein and other Der Spiegel editors were arrested on charges of treason. Despite a lack of sufficient authority, Strauss even went after the article's author, Conrad Ahlers, who was consequently arrested in Spain where he was on holiday. When the legal case collapsed, the scandal led to a major shake-up in chancellor Konrad Adenauer's cabinet, and Strauss had to stand down. The affair was generally received as an attack on the freedom of the press. Since then, Der Spiegel has repeatedly played a significant role in revealing political grievances and misdeeds, including the Flick Affair.[9]

In 2010, the magazine supported WikiLeaks in publishing leaked materials from the United States State Department, along with The Guardian, The New York Times, El País, and Le Monde[30] and in October 2013 with the help of former NSA contractor Edward Snowden unveiled the systematic wiretapping of Chancellor of Germany Angela Merkel's private cell phone over a period of over 10 years at the hands of the National Security Agency's Special Collection Service (SCS).[31]

According to a 2013 report by The New York Times, the magazine's leading role in German investigative journalism has diminished, since other German media outlets, including Süddeutsche Zeitung, Bild, ARD and ZDF, have become more involved in investigative reporting.[32]

In November 2023, Der Spiegel joined with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Paper Trail Media and 69 media partners including Distributed Denial of Secrets and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and more than 270 journalists in 55 countries and territories[33][34] to produce the 'Cyprus Confidential' report on the financial network which supports the regime of Vladimir Putin, mostly with connections to Cyprus, and showed Cyprus to have strong links with high-up figures in the Kremlin, some of whom have been sanctioned.[35][36] Government officials including Cyprus president Nikos Christodoulides[37] and European lawmakers[38] began responding to the investigation's findings in less than 24 hours,[39] calling for reforms and launching probes.[40][41]

Fake news scandals

Summarize

Perspective

Der Spiegel has reportedly been involved in controversies over publishing fake news.[42][43][44]

2018 fabrication scandal

On 19 December 2018, Der Spiegel made public that reporter Claas Relotius had admitted that he had "falsified his articles on a grand scale", inventing facts, persons and quotations in at least 14 of his stories.[18][19] The magazine uncovered the fraud after a co-author of one of Relotius's stories, Juan Moreno, became suspicious of the veracity of Relotius's contributions and gathered evidence against him.[19] Relotius resigned, telling the magazine that he was "sick" and needed to get help. Der Spiegel left his articles accessible, but with a notice referring to the magazine's ongoing investigation into the fabrications.[18]

The Wall Street Journal cited a former Der Spiegel journalist who said "some of the articles at issue appeared to confirm certain German stereotypes about Trump voters, asking "was this possible because of ideological bias?"[45] An apology ensued from Der Spiegel for looking for a cliché of a Trump-voting town, and not finding it.[46] Mathias Bröckers, former Die Tageszeitung editor, wrote: "the imaginative author simply delivered what his superiors demanded and fit into their spin".[47] American journalist James Kirchick claimed in The Atlantic that "Der Spiegel has long peddled crude and sensational anti-Americanism."[48][49] The US Ambassador to Germany Richard Grenell also wrote a letter to the magazine's editors, saying that Claas Relotius's journalism showed an anti-American bias. He also expressed shock at how Der Spiegel allowed "anti-American coverage."[50]

2022 fake news about refugee death at the Greece–Turkey borders

In the summer of 2022, Der Spiegel published three articles and a podcast regarding the death of a refugee girl named "Maria" on an islet in the Evros river at the Greece–Turkey borders, accusing Greece of failing to aid the refugees which caused the girl's death. But at the end of December 2022, the magazine retracted the articles and the podcast.[51][52] Greek newspaper Kathimerini reported that the story had been fabricated.[53][54][55] In 2023, the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) wrote that this story was "one of the largest fake news breakdowns since Claas Relotius."[56]

People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran

The Hamburg state court ordered Der Spiegel in 2019 to remove unsupported claims from an article that accused the People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran (MEK) of "torture" and "psychoterror."[57]

Bans

In January 1978 the office of Der Spiegel in East Berlin was closed by the East German government following the publication of critical articles against the conditions in the country.[58] A special 25 March 2008 edition of the magazine on Islam was banned in Egypt in April 2008 for publishing material deemed by authorities to be insulting Islam and Muhammed.[59][60]

Head office

Der Spiegel began moving into its current head office in HafenCity in September 2011. The facility was designed by Henning Larsen Architects of Denmark. The magazine's offices were previously in a high-rise building with 8,226 square metres (88,540 sq ft) of office space.[61]

Editors-in-chief

- 1962–1968: Claus Jacobi

- 1968–1973: Günter Gaus

- 1973–1986: Erich Böhme and Johannes K. Engel

- 1986–1989: Erich Böhme and Werner Funk

- 1989–1994: Hans Werner Kilz and Wolfgang Kaden

- 1994–2008: Stefan Aust

- 2008–2011: Mathias Müller von Blumencron and Georg Mascolo

- 2011–2013: Georg Mascolo[32]

- 2013–2014: Wolfgang Büchner[62]

- 13 January 2015 – 15 October 2018: Klaus Brinkbäumer

- 1 January 2019: Steffen Klusmann and Barbara Hans

- 25 May 2023: Dirk Kurbjuweit

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.