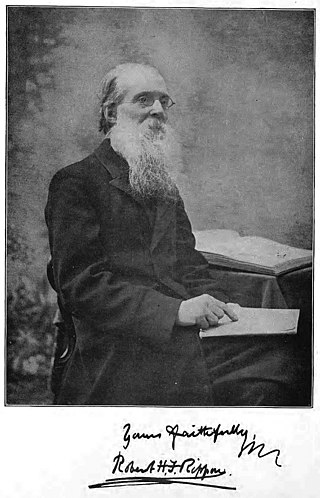

Robert H. F. Rippon

English zoologist, entomologist and illustrator From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Robert Henry Fernando Rippon (c. 1836[1] – 16 January 1917[2]) was an English zoologist, entomologist and illustrator. He was a musician for a while but took a keen amateur interest in entomology and published a major multi-volume work on the birdwing butterflies, the Icones Ornithopterum (1898-1906). He also wrote Lilliebright; or, Wisdom and Folly: A Fairy Tale, and Other Tales (1856), and a semi-autobiographical novel, Victor; Or, Lessons of Life. a Tale Founded on Fact (1864).[2]

Life and work

Summarize

Perspective

Rippon was born in Bocking, Essex, the first son of John and Martha. His father John is recorded in the 1841 census as a professor of music at Braintree, Essex.[2] Robert Rippon's interests included poetry and music, with several piano compositions to his credit.[2] In 1861 Robert's lived in Reading, Berkshire and his profession was recorded as professor of music.

Around 1876 he moved to London and took to zoological illustration for a living. He produced several plates for Frederick DuCane Godman and Osbert Salvin's Biologia Centrali-Americana. He was a close friend of John Obadiah Westwood, to whom he dedicated the first volume of his magnum opus, the illustrated monograph Icones Ornithopterorum (1898 to 1906), about the birdwing butterflies. It was initially planned for 20 parts but later made up of 25 parts which were to be bound into two volumes. The second volume was dedicated to Lord Walter Rothschild. This work included 111 plates, all of which were illustrated and hand coloured by himself. He was also a friend of the entomologist George Robert Crotch,[1] and the naturalist Philip Henry Gosse.[3]

He also designed pottery for the Watcombe Pottery.[2]

Rippon married Sarah Anne Pope in 1858 at Wycombe and they had a son, Edrick Victor Rippon (born 1864), who took an interest in molluscs and insects, living later in Toronto,[2] where he became the first president of the Toronto Entomological Society.[4] They also had a daughter named Faithful Faerie (also known as Faithful Isabel, or “Fran”, born 1868).[2] Sarah died in 1870 and he later married Eliza Balfour Moore (d. 1926) with whom he had a son named Felix in 1878.[2] Rippon is noted as a religious person and a teetotaler. He objected to corporal and capital punishment.[2] Towards the end of his life he lived at Upper Norwood and wished that his collection could be acquired in full rather than get broken up. After his death, his private collection was offered for £1000 by his widow to the British Museum. It was thought to be overpriced and Emily Mary Bowdler Sharpe, daughter of Richard Bowdler Sharpe, was assigned to evaluate the value of the collections. She evaluated it at about £500-600, noting that the specimens were good, well labelled and worthy of acquisition. William Evans Hoyle wrote to Lord Rhondda suggesting that the value of the collection was worth more than the £1000 sought by Mrs Rippon. The collection also included bird skins whose fate is unknown, but the collection of insects was bought by Lord Rhondda and donated to the National Museum of Wales; it included more than 105,000 specimens.[1] His son Victor also collected beetles and many of these are in the Royal Ontario Museum.[2]

The Australian ladybird species Coelophora ripponi was named in his honour by Crotch in his 1874 A Revision of the Coleopterous Family Coccinellidae, a posthumously-published work for which Rippon checked the proofs and wrote the preface.[5] In 1979, the species was determined to be a synonym of Coelophora inaequalis.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.