Paradigm shift

Fundamental change in ideas and practices within a scientific discipline From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A paradigm shift is a fundamental change in the basic concepts and experimental practices of a scientific discipline. It is a concept in the philosophy of science that was introduced and brought into the common lexicon by the American physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn. Even though Kuhn restricted the use of the term to the natural sciences, the concept of a paradigm shift has also been used in numerous non-scientific contexts to describe a profound change in a fundamental model or perception of events.

Kuhn presented his notion of a paradigm shift in his influential book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962).

Kuhn contrasts paradigm shifts, which characterize a Scientific Revolution, to the activity of normal science, which he describes as scientific work done within a prevailing framework or paradigm. Paradigm shifts arise when the dominant paradigm under which normal science operates is rendered incompatible with new phenomena, facilitating the adoption of a new theory or paradigm.[1]

As one commentator summarizes:

Kuhn acknowledges having used the term "paradigm" in two different meanings. In the first one, "paradigm" designates what the members of a certain scientific community have in common, that is to say, the whole of techniques, patents and values shared by the members of the community. In the second sense, the paradigm is a single element of a whole, say for instance Newton's Principia, which, acting as a common model or an example... stands for the explicit rules and thus defines a coherent tradition of investigation. Thus the question is for Kuhn to investigate by means of the paradigm what makes possible the constitution of what he calls "normal science". That is to say, the science which can decide if a certain problem will be considered scientific or not. Normal science does not mean at all a science guided by a coherent system of rules, on the contrary, the rules can be derived from the paradigms, but the paradigms can guide the investigation also in the absence of rules. This is precisely the second meaning of the term "paradigm", which Kuhn considered the most new and profound, though it is in truth the oldest.[2]

History

Summarize

Perspective

The nature of scientific revolutions has been studied by modern philosophy since Immanuel Kant used the phrase in the preface to the second edition of his Critique of Pure Reason (1787). Kant used the phrase "revolution of the way of thinking" (Revolution der Denkart) to refer to Greek mathematics and Newtonian physics. In the 20th century, new developments in the basic concepts of mathematics, physics, and biology revitalized interest in the question among scholars.

Original usage

In his 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn explains the development of paradigm shifts in science into four stages:

- Normal science – In this stage, which Kuhn sees as most prominent in science, a dominant paradigm is active. This paradigm is characterized by a set of theories and ideas that define what is possible and rational to do, giving scientists a clear set of tools to approach certain problems. Some examples of dominant paradigms that Kuhn gives are: Newtonian physics, caloric theory, and the theory of electromagnetism.[4] Insofar as paradigms are useful, they expand both the scope and the tools with which scientists do research. Kuhn stresses that, rather than being monolithic, the paradigms that define normal science can be particular to different people. A chemist and a physicist might operate with different paradigms of what a helium atom is.[5] Under normal science, scientists encounter anomalies that cannot be explained by the universally accepted paradigm within which scientific progress has thereto been made.

- Extraordinary research – When enough significant anomalies have accrued against a current paradigm, the scientific discipline is thrown into a state of crisis. To address the crisis, scientists push the boundaries of normal science in what Kuhn calls “extraordinary research”, which is characterized by its exploratory nature.[6] Without the structures of the dominant paradigm to depend on, scientists engaging in extraordinary research must produce new theories, thought experiments, and experiments to explain the anomalies. Kuhn sees the practice of this stage – “the proliferation of competing articulations, the willingness to try anything, the expression of explicit discontent, the recourse to philosophy and to debate over fundamentals” – as even more important to science than paradigm shifts.[7]

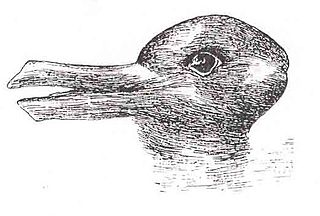

- Adoption of a new paradigm – Eventually a new paradigm is formed, which gains its own new followers. For Kuhn, this stage entails both resistance to the new paradigm, and reasons for why individual scientists adopt it. According to Max Planck, "a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it."[8] Because scientists are committed to the dominant paradigm, and paradigm shifts involve gestalt-like changes, Kuhn stresses that paradigms are difficult to change. However, paradigms can gain influence by explaining or predicting phenomena much better than before (i.e., Bohr's model of the atom) or by being more subjectively pleasing. During this phase, proponents for competing paradigms address what Kuhn considers the core of a paradigm debate: whether a given paradigm will be a good guide for future problems – things that neither the proposed paradigm nor the dominant paradigm are capable of solving currently.[9]

- Aftermath of the scientific revolution – In the long run, the new paradigm becomes institutionalized as the dominant one. Textbooks are written, obscuring the revolutionary process.

Features

Summarize

Perspective

Paradigm shifts and progress

A common misinterpretation of paradigms is the belief that the discovery of paradigm shifts and the dynamic nature of science (with its many opportunities for subjective judgments by scientists) are a case for relativism:[10] the view that all kinds of belief systems are equal. Kuhn vehemently denies this interpretation[11] and states that when a scientific paradigm is replaced by a new one, albeit through a complex social process, the new one is always better, not just different.

Incommensurability

These claims of relativism are, however, tied to another claim that Kuhn does at least somewhat endorse: that the language and theories of different paradigms cannot be translated into one another or rationally evaluated against one another—that they are incommensurable. This gave rise to much talk of different peoples and cultures having radically different worldviews or conceptual schemes—so different that whether or not one was better, they could not be understood by one another. However, the philosopher Donald Davidson published the highly regarded essay "On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme"[12] in 1974 arguing that the notion that any languages or theories could be incommensurable with one another was itself incoherent. If this is correct, Kuhn's claims must be taken in a weaker sense than they often are. Furthermore, the hold of the Kuhnian analysis on social science has long been tenuous, with the wide application of multi-paradigmatic approaches in order to understand complex human behaviour.[13]

Gradualism vs. sudden change

Paradigm shifts tend to be most dramatic in sciences that appear to be stable and mature, as in physics at the end of the 19th century. At that time, physics seemed to be a discipline filling in the last few details of a largely worked-out system.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn wrote, "Successive transition from one paradigm to another via revolution is the usual developmental pattern of mature science" (p. 12). Kuhn's idea was itself revolutionary in its time as it caused a major change in the way that academics talk about science. Thus, it could be argued that it caused or was itself part of a "paradigm shift" in the history and sociology of science. However, Kuhn would not recognise such a paradigm shift. In the social sciences, people can still use earlier ideas to discuss the history of science.

Philosophers and historians of science, including Kuhn himself, ultimately accepted a modified version of Kuhn's model, which synthesizes his original view with the gradualist model that preceded it.[14]

Examples

Summarize

Perspective

Natural sciences

Some of the "classical cases" of Kuhnian paradigm shifts in science are:

- 1543 – The transition in cosmology from a Ptolemaic cosmology to a Copernican one.[15]

- 1543 – The acceptance of the work of Andreas Vesalius, whose work De humani corporis fabrica corrected the numerous errors in the previously held system of human anatomy created by Galen.[16]

- 1687 – The transition in mechanics from Aristotelian mechanics to classical mechanics.[17]

- 1783 – The acceptance of Lavoisier's theory of chemical reactions and combustion in place of phlogiston theory, known as the chemical revolution.[18][19]

- The transition in optics from geometrical optics to physical optics with Augustin-Jean Fresnel's wave theory.[20]

- 1826 – The discovery of hyperbolic geometry.[21]

- 1830 to 1833 – Geologist Charles Lyell published Principles of Geology, which not only put forth the concept of uniformitarianism, which was in direct contrast to the popular geological theory, at the time, catastrophism, but also utilized geological proof to determine that the age of the Earth was older than 6,000 years, which was previously held to be true.

- 1859 – The revolution in evolution from goal-directed change to Charles Darwin's natural selection.[22]

- 1880 – The germ theory of disease began overtaking Galen's miasma theory.

- 1905 – The development of quantum mechanics, which replaced classical mechanics at microscopic scales.[23]

- 1887 to 1905 – The transition from the luminiferous aether present in space to electromagnetic radiation in spacetime.[24]

- 1919 – The transition between the worldview of Newtonian gravity and general relativity.

- 1920 – The emergence of the modern view of the Milky Way as just one of countless galaxies within an immeasurably vast universe following the results of the Smithsonian's Great Debate between astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis.

- 1952 – Chemists Stanley Miller and Harold Urey perform an experiment which simulated the conditions on the early Earth that favored chemical reactions that synthesized more complex organic compounds from simpler inorganic precursors, kickstarting decades of research into the chemical origins of life.

- 1964 – The discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation leads to the Big Bang theory being accepted over the steady state theory in cosmology.

- 1965 – The acceptance of plate tectonics as the explanation for large-scale geologic changes.

- 1969 – Astronomer Victor Safronov, in his book Evolution of the protoplanetary cloud and formation of the Earth and the planets, developed the early version of the current accepted theory of planetary formation.

- 1974 – The November Revolution, with the discovery of the J/psi meson, and the acceptance of the existence of quarks and the Standard Model of particle physics.

- 1960 to 1985 – The acceptance of the ubiquity of nonlinear dynamical systems as promoted by chaos theory, instead of a laplacian world-view of deterministic predictability.[25]

Social sciences

In Kuhn's view, the existence of a single reigning paradigm is characteristic of the natural sciences, while philosophy and much of social science were characterized by a "tradition of claims, counterclaims, and debates over fundamentals."[26] Others have applied Kuhn's concept of paradigm shift to the social sciences.

- The movement known as the cognitive revolution moved away from behaviourist approaches to psychology and the acceptance of cognition as central to studying human behavior.

- Anthropologist Franz Boas published The Mind of Primitive Man, which integrated his theories concerning the history and development of cultures and established a program that would dominate American anthropology in the following years. His research, along with that of his other colleagues, combatted and debunked the claims being made by scholars at the time, given scientific racism and eugenics were dominant in many universities and institutions that were dedicated to studying humans and society. Eventually anthropology would apply a holistic approach, utilizing four subcategories to study humans: archaeology, cultural, evolutionary, and linguistic anthropology.

- At the turn of the 20th century, sociologists, along with other social scientists developed and adopted methodological antipositivism, which sought to uphold a subjective perspective when studying human activities pertaining to culture, society, and behavior. This was in stark contrast to positivism, which took its influence from the methodologies utilized within the natural sciences.

- First proposed by Ferdinand de Saussure in 1879, the laryngeal theory in Indo-European linguistics postulated the existence of "laryngeal" consonants in the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE), a theory that was confirmed by the discovery of the Hittite language in the early 20th century. The theory has since been accepted by the vast majority of linguists, paving the way for the internal reconstruction of the syntax and grammatical rules of PIE and is considered one of the most significant developments in linguistics since the initial discovery of the Indo-European language family.[27]

- The adoption of radiocarbon dating by archaeologists has been proposed as a paradigm shift because of how it greatly increased the time depth the archaeologists could reliably date objects from. Similarly the use of LIDAR for remote geospatial imaging of cultural landscapes, and the shift from processual to post-processual archaeology have both been claimed as paradigm shifts by archaeologists.[28]

- The Marginal Revolution, a development of economic theory in the late 19th century led by William Stanley Jevons in England, Carl Menger in Austria, and Léon Walras in Switzerland and France which explained economic behavior in terms of marginal utility.

Applied sciences

More recently, paradigm shifts are also recognisable in applied sciences:

- In medicine, the transition from "clinical judgment" to evidence-based medicine.[citation needed]

- In Artificial Intelligence, the transition from a knowledge-based to a data-driven paradigm has been discussed from 2010.[29]

Other uses

Summarize

Perspective

The term "paradigm shift" has found uses in other contexts, representing the notion of a major change in a certain thought pattern—a radical change in personal beliefs, complex systems or organizations, replacing the former way of thinking or organizing with a radically different way of thinking or organizing:

- M. L. Handa, a professor of sociology in education at O.I.S.E. University of Toronto, Canada, developed the concept of a paradigm within the context of social sciences. He defines what he means by "paradigm" and introduces the idea of a "social paradigm". In addition, he identifies the basic component of any social paradigm. Like Kuhn, he addresses the issue of changing paradigms, the process popularly known as "paradigm shift". In this respect, he focuses on the social circumstances that precipitate such a shift. Relatedly, he addresses how that shift affects social institutions, including the institution of education.[30]

- The concept has been developed for technology and economics in the identification of new techno-economic paradigms as changes in technological systems that have a major influence on the behaviour of the entire economy (Carlota Perez; earlier work only on technological paradigms by Giovanni Dosi). This concept is linked to Joseph Schumpeter's idea of creative destruction. Examples include the move to mass production and the introduction of microelectronics.[31]

- Two photographs of the Earth from space, "Earthrise" (1968) and "The Blue Marble" (1972), are thought [by whom?] to have helped to usher in the environmentalist movement, which gained great prominence in the years immediately following distribution of those images.[32][33]

- Hans Küng applies Thomas Kuhn's theory of paradigm change to the entire history of Christian thought and theology. He identifies six historical "macromodels": 1) the apocalyptic paradigm of primitive Christianity, 2) the Hellenistic paradigm of the patristic period, 3) the medieval Roman Catholic paradigm, 4) the Protestant (Reformation) paradigm, 5) the modern Enlightenment paradigm, and 6) the emerging ecumenical paradigm. He also discusses five analogies between natural science and theology in relation to paradigm shifts. Küng addresses paradigm change in his books, Paradigm Change in Theology[34] and Theology for the Third Millennium: An Ecumenical View.[35]

- In the later part of the 1990s, 'paradigm shift' emerged as a buzzword, popularized as marketing speak and appearing more frequently in print and publication.[36] In his book Mind The Gaffe, author Larry Trask advises readers to refrain from using it, and to use caution when reading anything that contains the phrase. It is referred to in several articles and books[37][38] as abused and overused to the point of becoming meaningless.

- The concept of technological paradigms has been advanced, particularly by Giovanni Dosi.

Criticism

Summarize

Perspective

In a 2015 retrospective on Kuhn,[39] the philosopher Martin Cohen describes the notion of the paradigm shift as a kind of intellectual virus – spreading from hard science to social science and on to the arts and even everyday political rhetoric today. Cohen claims that Kuhn had only a very hazy idea of what it might mean and, in line with the Austrian philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend, accuses Kuhn of retreating from the more radical implications of his theory, which are that scientific facts are never really more than opinions whose popularity is transitory and far from conclusive. Cohen says scientific knowledge is less certain than it is usually portrayed, and that science and knowledge generally is not the 'very sensible and reassuringly solid sort of affair' that Kuhn describes, in which progress involves periodic paradigm shifts in which much of the old certainties are abandoned in order to open up new approaches to understanding that scientists would never have considered valid before. He argues that information cascades can distort rational, scientific debate. He has focused on health issues, including the example of highly mediatised 'pandemic' alarms, and why they have turned out eventually to be little more than scares.[40]

See also

- Accelerating change – Perceived increase in the rate of technological change throughout history

- Attitude polarization – Tendency of a group to make more extreme decisions than the inclinations of its members

- Belief perseverance – Maintenance of a belief despite new information that firmly contradicts it

- Buckminster Fuller – American philosopher, architect and inventor (1895–1983)

- Cognitive bias – Systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment

- Conceptual model – Theoretical framework

- Confirmation bias – Bias confirming existing attitudes

- Copernican Revolution – 16th to 17th century intellectual revolution

- Critical juncture theory – Theory of large, discontinuous changes

- Cultural bias – Interpretation and judgement of phenomena by the standards of one's culture

- Disruptive innovation – Technological change

- Don Tapscott – Canadian businessman (author of Paradigm Shift)

- Epistemological break – Concept of knowledge theory

- Gaston Bachelard – French philosopher

- Globalization – Spread of world views, products, ideas, capital and labor

- Human history

- Infrastructure bias – the influence of existing social or scientific infrastructure on scientific observations

- Innovation – Practical implementation of improvements

- Inquiry – Any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem

- Kondratiev wave – Hypothesized cycle-like phenomena in the modern world economy

- Ludwik Fleck – Polish physician

- Modeling – Theoretical framework

- Mindset – Term in decision theory and general systems theory

- New world order (politics) – Period of history with a dramatic change in world political thought

- Planck's principle – Principle that scientific change is generational

- Scientific modelling – Scientific activity that produces models

- Statistical model – Type of mathematical model

- Systemic bias – Inherent tendency of a process to support particular outcomes

- Teachable moment – Time at which learning a particular idea becomes possible or easiest

- World view – Fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society

- Zeitgeist – Philosophical concept meaning "spirit of the age"

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.