Render unto Caesar

Phrase attributed to Jesus in the synoptic gospels From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Render unto Caesar" is the beginning of a phrase attributed to Jesus in the synoptic gospels, which reads in full, "Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's" (Ἀπόδοτε οὖν τὰ Καίσαρος Καίσαρι καὶ τὰ τοῦ Θεοῦ τῷ Θεῷ).[1]

This phrase has become a widely quoted summary of the relationship between Christianity, secular government, and society. The original message, coming in response to a question of whether it was lawful for Jews to pay taxes to Caesar, gives rise to multiple possible interpretations about the circumstances under which it is desirable for Christians to submit to earthly authority.

Narrative

Summarize

Perspective

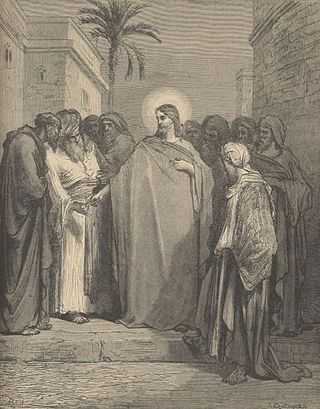

All three synoptic gospels state that hostile questioners tried to trap Jesus into taking an explicit and dangerous stand on whether Jews should or should not pay taxes to the Roman authorities. The accounts in Matthew 22:15–22 and Mark 12:13–17 say that the questioners were Pharisees and Herodians, while Luke 20:20–26 says only that they were "spies" sent by "teachers of the law and the chief priests".

They anticipated that Jesus would oppose the tax, as their purpose was "to hand him over to the power and authority of the governor".[2] The governor was Pilate, and he was the man responsible for the collecting of taxes in Roman Judea. Initially the questioners flattered Jesus by praising his integrity, impartiality, and devotion to truth. Then they asked him whether or not it is right for Jews to pay the taxes demanded by Caesar. In the Gospel of Mark[3] the additional, provocative question is asked, "Should we pay or shouldn't we?"

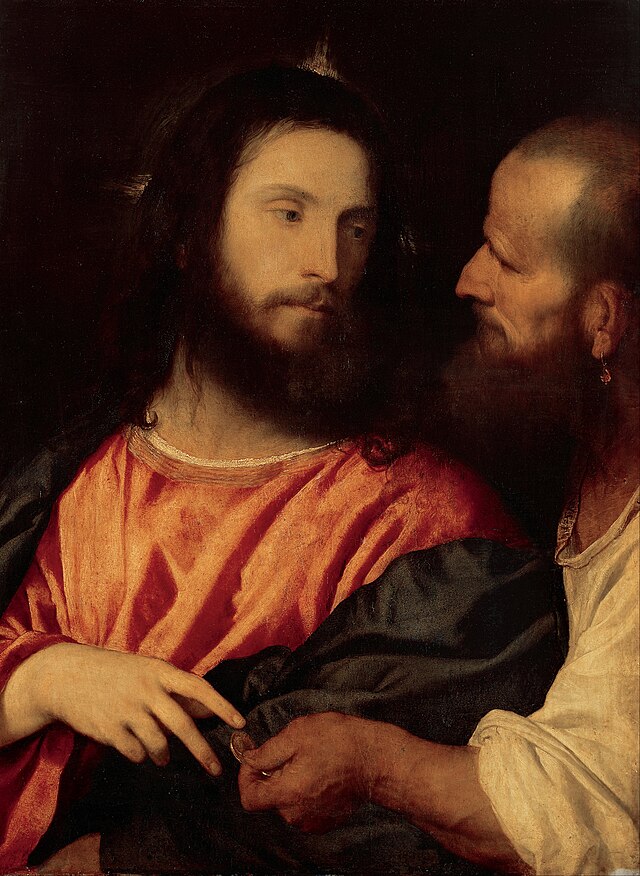

Jesus first called them hypocrites, and then asked one of them to produce a Roman coin that would be suitable for paying Caesar's tax. One of them showed him a Roman coin, and he asked them whose head and inscription were on it. They answered, "Caesar's," and he responded: "Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's".

The questioners were impressed. Matthew 22:22 states that they "marvelled" (ἐθαύμασαν); unable to trap him any further, and being satisfied with the answer, they went away.

A similar episode occurs in the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas (verse 100), but there the coin in question is gold. Importantly, in this non-canon gospel, Jesus adds, "and give me what is mine."[4] The same episode occurs in a fragment of the also apocryphal Egerton Gospel: Jesus is asked whether it is right to pay taxes to the rulers (i.e. the Romans), to which he becomes indignant and criticizes the questioners by quoting the Book of Isaiah; the fragment is interrupted immediately after that.[5]

Historical context

Summarize

Perspective

The coin

The text identifies the coin as a δηνάριον (dēnarion),[6] and it is usually thought that the coin was a Roman denarius with the head of Tiberius. The coin is also called the "tribute penny." The inscription reads "Ti[berivs] Caesar Divi Avg[vsti] F[ilivs] Avgvstvs" ("Caesar Augustus Tiberius, son of the Divine Augustus"). The reverse shows a seated female, usually identified as Livia depicted as Pax.[7]

However, it has been suggested that denarii were not in common circulation in Judaea during Jesus' lifetime and that the coin may have instead been an Antiochan tetradrachm bearing the head of Tiberius, with Augustus on the reverse.[8] Another suggestion often made is the denarius of Augustus with Caius and Lucius on the reverse, while coins of Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, and Germanicus are all considered possibilities.[9]

Tax resistance in Judaea

The taxes imposed on Judaea by Rome had led to riots.[10] New Testament scholar Willard Swartley writes:

The tax denoted in the text was a specific tax... It was a poll tax, a tax instituted in A.D. 6. A census taken at that time (cf. Lk. 2:2) to determine the resources of the Jews provoked the wrath of the country. Judas of Galilee led a revolt (Acts 5:37), which was suppressed only with some difficulty. Many scholars date the origin of the Zealot party and movement to this incident.[11]

The Jewish Encyclopedia says of the Zealots:

When, in the year 5, Judas of Gamala in Galilee started his organized opposition to Rome, he was joined by one of the leaders of the Pharisees, R. Zadok, a disciple of Shammai and one of the fiery patriots and popular heroes who lived to witness the tragic end of Jerusalem... The taking of the census by Quirinus, the Roman procurator, for the purpose of taxation was regarded as a sign of Roman enslavement; and the Zealots' call for stubborn resistance to the oppressor was responded to enthusiastically.

At his trial before Pontius Pilate, Jesus was accused of promoting resistance to Caesar's tax.

Then the whole company of them arose and brought him before Pilate. And they began to accuse him, saying, "We found this man misleading our nation and forbidding us to give tribute to Caesar, and saying that he himself is Christ, a king." (Luke 23:1–4)

Interpretations

Summarize

Perspective

This section possibly contains original research. (December 2017) |

The passage has been much discussed in the modern context of Christianity and politics, especially on the questions of separation of church and state and tax resistance.

Foreshadowing

When Jesus was later crucified, he was, in a sense, rendering unto Caesar the body that belonged to Caesar's (human, earthly) realm while devoting his soul to God. Augustine of Hippo suggested this interpretation in his Confessions, where he writes

He himself, the only-begotten, was created to be wisdom and justice and holiness for us, and he was counted among us, and he paid the reckoning, the tribute to Caesar.[12]

Separation of church and state

Jesus responds to Pontius Pilate about the nature of his kingdom: "My kingdom is not of this world. If my kingdom were of this world, my servants would have been fighting, that I might not be delivered over to the Jews. But now (or 'as it is') my kingdom is not from the world" (John 18:36); i.e., his religious teachings were separate from earthly political activity. This reflects a traditional division in Christian thought by which state and church have separate spheres of influence.[13] This can be interpreted in either a Catholic, or Thomist, way (Gelasian doctrine) or a Protestant, or Lockean, way (separation of church and state).

Tertullian, in De Idololatria, interprets Jesus as saying to render "the image of Caesar, which is on the coin, to Caesar, and the image of God, which is on man, to God; so as to render to Caesar indeed money, to God yourself. Otherwise, what will be God's, if all things are Caesar's?"[14]

Theonomic answer

H.B. Clark writes, "It is a doctrine of both Mosaic and Christian law that governments are divinely ordained and derive their powers from God. In the Old Testament it is asserted that 'power belongeth unto God,' (Psalms 62:11) that God 'removeth kings and setteth up kings,' (Daniel 2:21) and that 'the Most High ruleth in the kingdom of men, and giveth it to whomever He will' (Daniel 4:32). Similarly, in the New Testament, it is stated that '...there is no power but of God, the powers that be are ordained of God' (Romans 13:1)."[15]

R. J. Rushdoony expands, "In early America, there was no question, whatever the form of civil government, that all legitimate authority is derived from God... Under a biblical doctrine of authority, because 'the powers that be are ordained of God (Romans 13:1), all authority, whether in the home, school, state, church, or any other sphere, is subordinate authority and is under God and subject to His word.' This means, first, that all obedience is subject to the prior obedience to God and his Word, for 'We ought to obey God rather than men' (Acts 5:29; Acts 4:19). Although civil obedience is commanded, it is equally apparent that the prior requirement of obedience to God must prevail."[16]

Justification for following laws

Some read the phrase "Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar's" as unambiguous at least to the extent that it commands people to respect state authority and to pay the taxes it demands of them. Paul the Apostle also states in Romans 13 that Christians are obliged to obey all earthly authorities, stating that as they were introduced by God, disobedience to them equates to disobedience to God.

In this interpretation, Jesus asked his interrogators to produce a coin in order to demonstrate to them that by using his coinage they had already admitted the de facto rule of the emperor, and that therefore they should submit to that rule.[17]

Respecting obligations when enjoying advantages

Some see the parable as being Jesus' message to people that if they enjoy the advantages of a state such as Caesar's, as distinct from God's authority (for instance, by using its legal tender), they cannot subsequently choose to ignore the laws of such a state. Henry David Thoreau writes in Civil Disobedience:

Christ answered the Herodians according to their condition. "Show me the tribute-money," said he; – and one took a penny out of his pocket; – If you use money which has the image of Caesar on it, and which he has made current and valuable, that is, if you are men of the State, and gladly enjoy the advantages of Caesar's government, then pay him back some of his own when he demands it; "Render therefore to Caesar that which is Caesar's and to God those things which are God's" – leaving them no wiser than before as to which was which; for they did not wish to know.

Mennonite Dale Glass-Hess wrote:

It is inconceivable to me that Jesus would teach that some spheres of human activity lie outside the authority of God. Are we to heed Caesar when he says to go to war or support war-making when Jesus says in other places that we shall not kill? No! My perception of this incident is that Jesus does not answer the question about the morality of paying taxes to Caesar, but that he throws it back on the people to decide. When the Jews produce a denarius at Jesus' request, they demonstrate that they are already doing business with Caesar on Caesar's terms. I read Jesus' statement, "Give to Caesar..." as meaning "Have you incurred a debt in regard to Caesar! Then you better pay it off." The Jews had already compromised themselves. Likewise for us: we may refuse to serve Caesar as soldiers and even try to resist paying for Caesar's army. But the fact is that by our lifestyles we've run up a debt with Caesar, who has felt constrained to defend the interests that support our lifestyles. Now he wants paid back, and it's a little late to say that we don't owe anything. We've already compromised ourselves. If we're going to play Caesar's games, then we should expect to have to pay for the pleasure of their enjoyment. But if we are determined to avoid those games, then we should be able to avoid paying for them.[18]

Mohandas K. Gandhi shared this perspective. He wrote:

Jesus evaded the direct question put to him because it was a trap. He was in no way bound to answer it. He therefore asked to see the coin for taxes. And then said with withering scorn, "How can you who traffic in Caesar's coins and thus receive what to you are benefits of Caesar's rule refuse to pay taxes?" Jesus' whole preaching and practice point unmistakably to noncooperation, which necessarily includes nonpayment of taxes.[19]

Roman Catholic

The German theologian Justus Knecht gives the typical pro-government, Roman Catholic, interpretation:

Obedience to temporal authority. We are not only allowed, but commanded to obey the authority of the state, and to pay such taxes &c. as are a due; for the authority of the state is ordained by God to protect the lives and property of subjects. If there were no temporal authority, disorder, robbery, murder &c. would be rampant; and, therefore, as the authority of the state exists for the good of subjects, it is the duty of these last to pay those taxes &c. without which it cannot be kept up.[20]

Tax resistance

Mennonite pastor John K. Stoner spoke for those who interpret the parable as permitting or even encouraging tax resistance: "We are war tax resisters because we have discovered some doubt as to what belongs to Caesar and what belongs to God, and have decided to give the benefit of the doubt to God."[21]

American Quaker war tax resistance

As American Quaker war tax resistance developed during the 17th through 19th centuries, the resisters had to find a way to reconcile their tax resistance with the "Render unto Caesar" verse and other verses from the New Testament that encourage submission to the government. Here are a few examples:

Around 1715, a pseudonymous author, "Philalethes," published a pamphlet entitled Tribute to Cæsar, How paid by the Best Christians... in which he argued that while Christians must pay "general" taxes, a tax that is explicitly for war purposes is the equivalent to an offering on an altar to a pagan god, and this is forbidden.[22]

In 1761, Joshua Evans put it this way:

Others would term it stubbornness in me, or contrary to the doctrine of Christ, concerning rendering to Caesar his due. But as I endeavored to keep my mind in a state of humble quietude, I was favored to see through such groundless arguments; there being nothing on the subject of war, or favorable to it, to be found in that text. Although I have been willing to pay my money for the use of civil government, when legally called for; yet have I felt restrained by a conscientious motive, from paying towards the expense of killing men, women and children, or laying towns and countries waste.[23]

In 1780, Samuel Allinson circulated a letter on the subject of tax resistance, in which he insisted that what was due to Caesar was only what Caesar would not use for antichristian purposes:

...the question put to our Savior on the point was with evil intention to ensnare and render him culpable to one of the great parties or sects then existing, who differed about the payment of taxes, his answer, though conclusive, was so wisely framed that it left them still in doubt, what things belonged to Cæsar and what to God, thus he avoided giving either of them offence which he must inevitably have done by a determination that tribute indefinitely was due to Cæsar. Our first and principle obedience is due to the Almighty, even in contradiction to man, "We ought to obey God rather than men" (Acts 5:29). Hence, if tribute is demanded for a use that is antichristian, it seems right for every Christian to deny it, for Cæsar can have no title to that which opposes the Lord's command.[24]

In 1862, Joshua Maule wrote that he felt that the "Render unto Caesar" instruction was compatible with war tax resistance, as there was no reason to believe for certain that the tax referred to in that episode had any connection to war:

The words of Christ, "Render to Cæsar the things that are Cæsar's, and to God the things that are God's," have often been brought forward as evidence that He approved of paying all taxes; it being said, in connection, that Cæsar was then engaged in war. The distinction, however, is sufficiently clear: the things that were Cæsar's were, doubtless, those which appertain to the civil government; the things which belong to God are, surely, a clear and full obedience to His commands and to His laws. We know that all the precepts and commands of Christ which can be applied in reference to this subject are of one tendency, enjoining "peace on earth and good-will to men." We do not know, after all, however, what was the exact nature and use of the tribute collected in those days, nor what were the situation and circumstances in which Christians or others were then placed in regard to such things.[25]

Christian anarchist

The less you have of Caesar's, the less you have to render to Caesar.

— Dorothy Day, The Catholic Worker

Christian anarchists do not interpret Matthew 22:21 as advocating support for taxes but as further advice to free oneself from material attachment. Jacques Ellul believes the passage shows that Caesar may have rights over the money that he produces, but not things that are made by God, as he explains:[26]

Render unto Caesar..." in no way divides the exercise of authority into two realms....They were said in response to another matter: the payment of taxes, and the coin. The mark on the coin is that of Caesar; it is the mark of his property. Therefore give Caesar this money; it is his. It is not a question of legitimizing taxes! It means that Caesar, having created money, is its master. That's all. Let us not forget that money, for Jesus, is the domain of Mammon, a satanic domain!

Ammon Hennacy interpreted Matthew 22:21 slightly differently. He was on trial for civil disobedience and was asked by the judge to reconcile his tax resistance with Jesus' instructions. "I told him Caesar was getting too much around here and someone had to stand up for God." Elsewhere, he interpreted the story in this way:

[Jesus] was asked if He believed in paying taxes to Caesar. In those days different districts had different money and the Jews had to change their money into that of Rome, so Jesus asked, not for a Jewish coin, but for a coin with which tribute was paid, saying "Why tempt me?" Looking at the coin He asked whose image and superscription was there inscribed and was told that it was Caesar's. Those who tried to trick Him knew that if He said that taxes were to be paid to Caesar He would be attacked by the mobs who hated Caesar, and if He refused to pay taxes there would always be some traitor to turn Him in. His mission was not to fight Caesar as Barabbas had done, but it was to chase the moneychangers out of the Temple and to establish His own Church. Whether He winked as much as to say that any good Jew knew that Caesar did not deserve a thing as He said, "Render unto Caesar what is Caesar's and unto God what is God's," or not, no one knows. ...Despite what anyone says each of us has to decide for himself whether to put the emphasis upon pleasing Caesar or pleasing God. We may vary in our reasons for drawing the line here or there as to how much we render unto Caesar. I make my decision when I remember that Christ said to the woman caught in sin, "Let him without sin first cast a stone at her." I remember His "Forgive seventy times seven," which means no Caesar at all with his courts, prisons and war.[27]

Versions

Summarize

Perspective

The extracanonical Gospel of Thomas also has a version, which reads in the Stephen Patterson and Marvin Meyer Version 100:[28]

They showed Jesus a gold coin and said to him, "The Roman emperor's people demand taxes from us." He said to them, "Give the emperor what belongs to the emperor, give God what belongs to God, and give me what is mine."

The fragmentary Egerton Gospel in the Scholar's Version translation (found in The Complete Gospels) 3:1–6 reads:[29]

They come to him and interrogate him as a way of putting him to the test. They ask, "Teacher, Jesus, we know that you are [from God], since the things you do put you above all the prophets. Tell us, then, is it permissible to pay to rulers what is due them? Should we pay them or not?" Jesus knew what they were up to, and became indignant. Then he said to them, "Why do you pay me lip service as a teacher, but not [do] what I say? How accurately Isaiah prophesied about you when he said, 'This people honors me with their lips, but their heart stays far away from me; their worship of me is empty, [because they insist on teachings that are human] commandments [...]'

Modern references

In the United States Supreme Court case of Tyler v. Hennepin County (2023), chief justice John Roberts referenced the phrase in the court's opinion regarding the Takings Clause and state property taxes. The chief justice explained the court's holding by stating that "[t]he taxpayer must render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, but no more."[30]

See also

- Caesaropapism

- Christianity and politics

- Coin in the fish's mouth

- Doctrine of the two kingdoms

- Fiscus Judaicus

- Parables of Jesus

- King Canute and the tide

- Romans 13, another Biblical discussion of how Christians should interact with secular authorities

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.