Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

R (programming language)

Programming language for statistics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

R is a programming language for statistical computing and data visualization. It has been widely adopted in the fields of data mining, bioinformatics, data analysis, and data science.[9]

The core R language is extended by a large number of software packages, which contain reusable code, documentation, and sample data. Some of the most popular R packages are in the tidyverse collection, which enhances functionality for visualizing, transforming, and modelling data, as well as improves the ease of programming (according to the authors and users).[10]

R is free and open-source software distributed under the GNU General Public License.[3][11] The language is implemented primarily in C, Fortran, and R itself. Precompiled executables are available for the major operating systems (including Linux, MacOS, and Microsoft Windows).

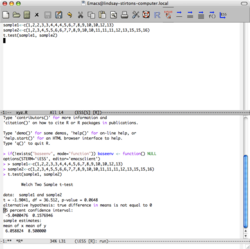

Its core is an interpreted language with a native command line interface. In addition, multiple third-party applications are available as graphical user interfaces; such applications include RStudio (an integrated development environment) and Jupyter (a notebook interface).

Remove ads

History

Co-originators of the R language

R was started by professors Ross Ihaka and Robert Gentleman as a programming language to teach introductory statistics at the University of Auckland.[12] The language was inspired by the S programming language, with most S programs able to run unaltered in R.[6] The language was also inspired by Scheme's lexical scoping, allowing for local variables.[1]

The name of the language, R, comes from being both an S language successor and the shared first letter of the authors, Ross and Robert.[13] In August 1993, Ihaka and Gentleman posted a binary file of R on StatLib — a data archive website.[14] At the same time, they announced the posting on the s-news mailing list.[15] On 5 December 1997, R became a GNU project when version 0.60 was released.[16] On 29 February 2000, the 1.0 version was released.[17]

Remove ads

Packages

Summarize

Perspective

R packages are collections of functions, documentation, and data that expand R.[18] For example, packages can add reporting features (using packages such as RMarkdown, Quarto,[19] knitr, and Sweave) and support for various statistical techniques (such as linear, generalized linear and nonlinear modeling, classical statistical tests, spatial analysis, time-series analysis, and clustering). Ease of package installation and use have contributed to the language's adoption in data science.[20]

Immediately available when starting R after installation, base packages provide the fundamental and necessary syntax and commands for programming, computing, graphics production, basic arithmetic, and statistical functionality.[21]

An example is the tidyverse collection of R packages, which bundles several subsidiary packages to provide a common API. The collection specializes in tasks related to accessing and processing "tidy data",[22] which are data contained in a two-dimensional table with a single row for each observation and a single column for each variable.[23]

Installing a package occurs only once. For example, to install the tidyverse collection:[23]

> install.packages("tidyverse")

To load the functions, data, and documentation of a package, one calls the library() function. To load the tidyverse collection, one can execute the following code:[a]

> # The package name can be enclosed in quotes

> library("tidyverse")

> # But the package name can also be used without quotes

> library(tidyverse)

The Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) was founded in 1997 by Kurt Hornik and Friedrich Leisch to host R's source code, executable files, documentation, and user-created packages.[24] CRAN's name and scope mimic the Comprehensive TeX Archive Network (CTAN) and the Comprehensive Perl Archive Network (CPAN).[24] CRAN originally had only three mirror sites and twelve contributed packages.[25] As of 30 June 2025[update], it has 90 mirrors[26] and 22,390 contributed packages.[27] Packages are also available in repositories such as R-Forge, Omegahat, and GitHub.[28][29][30]

To provide guidance on the CRAN web site, its Task Views area lists packages that are relevant for specific topics; sample topics include causal inference, finance, genetics, high-performance computing, machine learning, medical imaging, meta-analysis, social sciences, and spatial statistics.

The Bioconductor project provides packages for genomic data analysis, complementary DNA, microarray, and high-throughput sequencing methods.

Remove ads

Community

Summarize

Perspective

There are three main groups that help support R software development:

- The R Core Team was founded in 1997 to maintain the R source code.

- The R Foundation for Statistical Computing was founded in April 2003 to provide financial support.

- The R Consortium is a Linux Foundation project to develop R infrastructure.

The R Journal is an open access, academic journal that features short to medium-length articles on the use and development of R. The journal includes articles on packages, programming tips, CRAN news, and foundation news.

The R community hosts many conferences and in-person meetups.[b] These groups include:

- UseR!: an annual international R user conference (website)

- Directions in Statistical Computing (DSC) (website)

- R-Ladies: an organization to promote gender diversity in the R community (website)

- SatRdays: R-focused conferences held on Saturdays (website)

- Data Science & AI Conferences (website)

- posit::conf (formerly known as rstudio::conf) (website)

On social media sites such as Twitter, the hashtag #rstats can be used to follow new developments in the R community.[31]

Examples

Summarize

Perspective

Hello, World!

The following is a "Hello, World!" program:

> print("Hello, World!")

[1] "Hello, World!"

Here is an alternative version, which uses the cat() function:

> cat("Hello, World!")

Hello, World!

Basic syntax

The following examples illustrate the basic syntax of the language and use of the command-line interface.[c]

In R, the generally preferred assignment operator is an arrow made from two characters <-, although = can be used in some cases.[32]

> x <- 1:6 # Create a numeric vector in the current environment

> y <- x^2 # Similarly, create a vector based on the values in x.

> print(y) # Print the vector’s contents.

[1] 1 4 9 16 25 36

> z <- x + y # Create a new vector that is the sum of x and y

> z # Return the contents of z to the current environment.

[1] 2 6 12 20 30 42

> z_matrix <- matrix(z, nrow = 3) # Create a new matrix that transforms the vector z into a 3x2 matrix object

> z_matrix

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 2 20

[2,] 6 30

[3,] 12 42

> 2 * t(z_matrix) - 2 # Transpose the matrix; multiply every element by 2; subtract 2 from each element in the matrix; and then return the results to the terminal.

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 2 10 22

[2,] 38 58 82

> new_df <- data.frame(t(z_matrix), row.names = c("A", "B")) # Create a new dataframe object that contains the data from a transposed z_matrix, with row names 'A' and 'B'

> names(new_df) <- c("X", "Y", "Z") # Set the column names of the new_df dataframe as X, Y, and Z.

> print(new_df) # Print the current results.

X Y Z

A 2 6 12

B 20 30 42

> new_df$Z # Output the Z column

[1] 12 42

> new_df$Z == new_df['Z'] && new_df[3] == new_df$Z # The dataframe column Z can be accessed using the syntax $Z, ['Z'], or [3], and the values are the same.

[1] TRUE

> attributes(new_df) # Print information about attributes of the new_df dataframe

$names

[1] "X" "Y" "Z"

$row.names

[1] "A" "B"

$class

[1] "data.frame"

> attributes(new_df)$row.names <- c("one", "two") # Access and then change the row.names attribute; this can also be done using the rownames() function

> new_df

X Y Z

one 2 6 12

two 20 30 42

Structure of a function

R is able to create functions that add new functionality for code reuse.[33] Objects created within the body of the function (which are enclosed by curly brackets) remain accessible only from within the function, and any data type may be returned. In R, almost all functions and all user-defined functions are closures.[34]

The following is an example of creating a function to perform an arithmetic calculation:

# The function's input parameters are x and y.

# The function, named f, returns a linear combination of x and y.

f <- function(x, y) {

z <- 3 * x + 4 * y

# An explicit return() statement is optional--it could be replaced with simply `z` in this case.

return(z)

}

# As an alternative, the last statement executed in a function is returned implicitly.

f <- function(x, y) 3 * x + 4 * y

The following is some output from using the function defined above:

> f(1, 2) # 3 * 1 + 4 * 2 = 3 + 8

[1] 11

> f(c(1, 2, 3), c(5, 3, 4)) # Element-wise calculation

[1] 23 18 25

> f(1:3, 4) # Equivalent to f(c(1, 2, 3), c(4, 4, 4))

[1] 19 22 25

It is possible to define functions to be used as infix operators by using the special syntax `%name%`, where "name" is the function variable name:

> `%sumx2y2%` <- function(e1, e2) {e1 ^ 2 + e2 ^ 2}

> 1:3 %sumx2y2% -(1:3)

[1] 2 8 18

Since R version 4.1.0, functions can be written in a short notation, which is useful for passing anonymous functions to higher-order functions:[35]

> sapply(1:5, \(i) i^2) # here \(i) is the same as function(i)

[1] 1 4 9 16 25

Native pipe operator

In R version 4.1.0, a native pipe operator, |>, was introduced.[36] This operator allows users to chain functions together, rather than using nested function calls.

> nrow(subset(mtcars, cyl == 4)) # Nested without the pipe character

[1] 11

> mtcars |> subset(cyl == 4) |> nrow() # Using the pipe character

[1] 11

An alternative to nested functions is the use of intermediate objects, rather than the pipe operator:

> mtcars_subset_rows <- subset(mtcars, cyl == 4)

> num_mtcars_subset <- nrow(mtcars_subset_rows)

> print(num_mtcars_subset)

[1] 11

While the pipe operator can produce code that is easier to read, influential R programmers like Hadley Wickham suggest to chain together at most 10-15 lines of code using this operator and saving them into objects having meaningful names to avoid code obfuscation.[37]

Object-oriented programming

The R language has native support for object-oriented programming. There are two native frameworks, the so-called S3 and S4 systems. The former, being more informal, supports single dispatch on the first argument, and objects are assigned to a class simply by setting a "class" attribute in each object. The latter is a system like the Common Lisp Object System (CLOS), with formal classes (also derived from S) and generic methods, which supports multiple dispatch and multiple inheritance[38]

In the example below, summary() is a generic function that dispatches to different methods depending on whether its argument is a numeric vector or a factor:

> data <- c("a", "b", "c", "a", NA)

> summary(data)

Length Class Mode

5 character character

> summary(as.factor(data))

a b c NA's

2 1 1 1

Modeling and plotting

plot.lm() function). Mathematical notation is allowed in labels, as shown in the lower left plot.The R language has built-in support for data modeling and graphics. The following example shows how R can generate and plot a linear model with residuals.

# Create x and y values

x <- 1:6

y <- x^2

# Linear regression model: y = A + B * x

model <- lm(y ~ x)

# Display an in-depth summary of the model

summary(model)

# Create a 2-by-2 layout for figures

par(mfrow = c(2, 2))

# Output diagnostic plots of the model

plot(model)

The output from the summary() function in the preceding code block is as follows:

Residuals:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

3.3333 -0.6667 -2.6667 -2.6667 -0.6667 3.3333

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -9.3333 2.8441 -3.282 0.030453 *

x 7.0000 0.7303 9.585 0.000662 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

Residual standard error: 3.055 on 4 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.9583, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9478

F-statistic: 91.88 on 1 and 4 DF, p-value: 0.000662

Mandelbrot set

This example of a Mandelbrot set highlights the use of complex numbers. It models the first 20 iterations of the equation z = z2 + c, where c represents different complex constants.

To run this sample code, it is necessary to first install the package that provides the write.gif() function:

install.packages("caTools")

The sample code is as follows:

library(caTools)

jet.colors <-

colorRampPalette(

c("green", "pink", "#007FFF", "cyan", "#7FFF7F",

"white", "#FF7F00", "red", "#7F0000"))

dx <- 1500 # define width

dy <- 1400 # define height

C <-

complex(

real = rep(seq(-2.2, 1.0, length.out = dx), each = dy),

imag = rep(seq(-1.2, 1.2, length.out = dy), times = dx)

)

# reshape as matrix of complex numbers

C <- matrix(C, dy, dx)

# initialize output 3D array

X <- array(0, c(dy, dx, 20))

Z <- 0

# loop with 20 iterations

for (k in 1:20) {

# the central difference equation

Z <- Z^2 + C

# capture the results

X[, , k] <- exp(-abs(Z))

}

write.gif(

X,

"Mandelbrot.gif",

col = jet.colors,

delay = 100)

Remove ads

Version names

Summarize

Perspective

All R version releases from 2.14.0 onward have codenames that make reference to Peanuts comics and films.[39][40][41]

In 2018, core R developer Peter Dalgaard presented a history of R releases since 1997.[42] Some notable early releases before the named releases include the following:

- Version 1.0.0, released on 29 February 2000, a leap day

- Version 2.0.0, released on 4 October 2004, "which at least had a nice ring to it"[42]

The idea of naming R version releases was inspired by the naming system for Debian and Ubuntu versions. Dalgaard noted an additional reason for the use of Peanuts references in R codenames—the humorous observation that "everyone in statistics is a P-nut."[42]

Remove ads

Interfaces

Examples of user interfaces for R

- Screenshot of the RKWard front-end running on the KDE 4 environment

- R running in the emacs editor with the ESS package

R is installed with a command line console by default, but there are multiple ways to interface with the language:

- Integrated development environment (IDE):

- R.app[179] (OSX/macOS only)

- Rattle GUI

- R Commander

- RKWard

- RStudio

- Positron[180]

- Tinn-R[181]

- General-purpose IDEs:

- Eclipse via the StatET plugin

- Visual Studio via R Tools for Visual Studio.

- Source-code editors:

- Other scripting languages:

- Python (website)

- Perl (website)

- Ruby (source code)

- F# (website)

- Julia (source code).

- General-purpose programming languages:

- Java via the Rserve socket server

- .NET C# (website)

Statistical frameworks that use R in the background include Jamovi and JASP.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Implementations

The main R implementation is written primarily in C, Fortran, and R itself. Other implementations include the following:

- pretty quick R (pqR), by Radford M. Neal, which attempts to improve memory management.

- Renjin for the Java Virtual Machine.

- CXXR and Riposte[182] written in C++.

- Oracle's FastR built on GraalVM.

- TIBCO Enterprise Runtime for R (TERR) to integrate with Spotfire.[183] (The company also created S-Plus, an implementation of the S language.)

Microsoft R Open (MRO) was an R implementation. As of 30 June 2021, Microsoft began to phase out MRO in favor of the CRAN distribution.[184]

Remove ads

Commercial support

Although R is an open-source project, some companies provide commercial support:

- Oracle provides commercial support for its Big Data Appliance, which integrates R into its other products.

- IBM provides commercial support for execution of R within Hadoop.

See also

Notes

- This code displays to standard error a listing of all the packages that the tidyverse collection depends upon. The code may also display warnings showing namespace conflicts, which may typically be ignored.

- Information about conferences and meetings is available in a community-maintained list on GitHub, jumpingrivers

.github .io /meetingsR / - An expanded list of standard language features can be found in the manual "An Introduction to R", cran

.r-project .org /doc /manuals /R-intro .pdf

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads