Merlin (Robert de Boron poem)

French epic poem From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Merlin is a partly lost French epic poem written by Robert de Boron in Old French and dating from either the end of the 12th[2] or beginning of the 13th century.[3] The author reworked Geoffrey of Monmouth's material on the legendary Merlin, emphasising Merlin's power to prophesy and linking him to the Holy Grail.[4] The poem tells of his origin and early life as a redeemed Antichrist, his role in the birth of Arthur, and how Arthur became King of Britain. Merlin's story relates to Robert's two other reputed Grail poems, Joseph d'Arimathie and Perceval.[1] Its motifs became popular in medieval and later Arthuriana, notably the introduction of the sword in the stone, the redefinition of the Grail, and turning the previously peripheral Merlin into a key character in the legend of King Arthur.[1][5]

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (April 2025) |

| Merlin | |

|---|---|

| by Robert de Boron | |

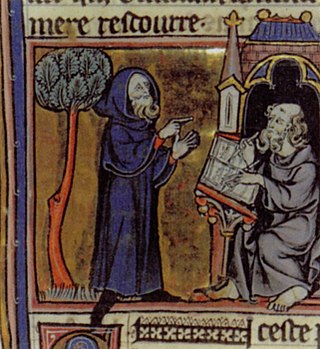

Merlin dictating the story of his life for Blaise to record in a 13th-century illustration for the prose version, Estoire de Merlin | |

| Written | Est. 1195–1210[1] |

| Country | Kingdom of France |

| Language | Old French |

| Series | Little Grail Cycle |

| Subject(s) | Arthurian legend, Holy Grail |

| Preceded by | Joseph of Arimathea |

| Followed by | Perceval |

The poem's medieval prose retelling and continuations, collectively the Prose Merlin,[2] became parts of the 13th-century Vulgate and Post-Vulgate cycles of prose chivalric romances. The Prose Merlin was versified into two English poems, Of Arthour and of Merlin and Henry Lovelich's Merlin. Its Post-Vulgate version was one of the major sources for Thomas Malory in writing Le Morte d'Arthur.

History

Summarize

Perspective

Writing Merlin, the French knight-poet Robert de Boron seems to have been influenced by Wace's Roman de Brut,[6][7] an Anglo-Norman adaptation of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae. Merlin is an allegorical tale, relating to the figure and works of Christ.[8] Only 504 lines of the work in its poetic form have survived to this day (in the manuscript BNF, fr. 20047). Nevertheless, its presumed contents are known from the prose version,[7] the latter preserved entirely in the original Old French as well as in a translation to Middle English.

Along with the poems attributed to Robert de Boron – the romance Joseph d'Arimathie, which survives only in prose, and Perceval, perhaps completely lost – Merlin forms a trilogy centered around the story of the Holy Grail.[1] Dubbed the "Little Grail Cycle", it rewrites had the Arthurian myth as being completely centered around the Holy Grail, here for the first time presented as a thoroughly Christian relic dating from the time of Christ. Brought from the Middle East to Britain by followers of Joseph of Arimathea, the Grail is eventually recovered by Arthur's knight Perceval, as foretold in one of the prophecies in Merlin. The cycle also greatly expands the role and part of Merlin in Arthurian legend, especially when compared to only one brief mention in all of the earlier influential poems by Chrétien de Troyes.[9]

An alternative theory postulated by Linda Gowans goes against the widely accepted conventional scholarship in deeming the prose text to be the original version of Merlin. She argues that the Old French poetic version is unfinished because its (unknown) writer has simply given up on it. She also doubts Robert's authorship of either of these works or of Perceval, attributing only Joseph to him.[10]

Synopsis

Summarize

Perspective

- Note: All names and events as in the later Middle English anonymous prose version (edited by John Conlee).

The first part introduces the character of Blaise, a cleric and clerk who is pictured as writing down Merlin's deeds, explaining how they came to be known and preserved. The text claims that it is actually only his translation of a Latin book written by a Blaise as dictated to him by Merlin himself.[11]

Merlin begins with the scene of a council of demons plotting to create the future Merlin as their agent on Earth to undo the work of Christ, but their plan is foiled and the mother names the child Merlin after her father. It continues with the story of the usurper king Voltiger (Vortigern) and his tower, featuring the seven-year-old Merlin with amazing prophetic powers. Following Voltiger's death, which Merlin also predicted, he assists the new king Pendragon and his brother Uter (Uther Pendragon), soon himself the king as Uterpendragon after the death of the original Pendragon at Salisbury. Following the bloody war against Saxon invaders, he erects Stonehenge as the burial place for the fallen Britons and eventually inspires the creation of the Round Table.

This is followed by the account of Uter's war with the Duke of Tintagel (here unnamed, but known as Gorlois in general Arthurian tradition) for the latter's wife Ygerne (Igraine), during which Merlin's magic, including many instances of shapeshifting, enables Uter to sleep with Ygerne and conceive Arthur, destined to become the Emperor of Rome. After Uter kills his rival and forcibly marries Ygerne, the newborn Arthur is given into the foster care of Antor (Ector), while Ygerne's daughters from the previous marriage are wed to King Lot and King Ventres (Nentres), and her illegitimate daughter Morgan is sent away to a nunnery and becomes known as Morgan le Fay (the first account of Morgan being Igraine's daughter and learning magic in a convent[12]).

The poem seems to have ended with the later "sword in the stone" story, in which Arthur proves he is to become Britain's high king by a divine destiny. This has been the first instance of this motif to appear in Arthurian literature and has become iconic after being repeated almost exactly in Thomas Malory's popular Le Morte d'Arthur.[2]

The following is the complete text of the mid-15th-century English translation (medieval English versions replaced the Anglo-Saxon enemies of Britain with the Saracens, the Danes, or just unidentified heathens), with modern conventions for punctuation and capitalization, of the prose version (sans the sequels):

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Prose Merlin and its continuations

The poem Merlin itself was recast into prose c. 1210 as the Prose Merlin by authors unknown (highly possibly a single author,[13] perhaps Robert himself[14]). Known as the Merlin Proper, it was then extended by a lengthy sequel sometimes known as the Suite du Roman de Merlin to become the early 13th-century chivalric romance Estoire de Merlin (History of Merlin), also known as the Vulgate Merlin.

The Estoire de Merlin constitutes one of the volumes of the vast Vulgate Cycle also known as the Lancelot-Grail cycle as probably a late addition to it.[13] This continuation diverges from Robert's Little Grail Cycle and no longer use his name as the author.[15] Its later major redaction, the Post-Vulgate Cycle, also begins with material drawn directly from Joseph and Merlin.[16] The Post-Vulgate manuscript known as the Huth Merlin actually attributes the authorship of the entire Post-Vulgate Cycle to Robert, making it sometimes dubbed the "Pseudo-Robert de Boron Cycle" (or "Pseudo-Boron Cycle").

The first of these prose continuations, included in the Vulgate Estoire du Merlin, is the Merlin Continuation also known as the Vulgate Suite du Merlin,[17] the so-called 'historical' sequel telling about the various wars of Arthur and the role of Merlin in them, also focusing on Gawain as the third main character.[2] The second, included in the later Post-Vulgate Suite du Merlin (Suite-Huth or the Huth Merlin[18]), is a 'romantic' sequel that includes elements of the Vulgate Lancelot.[7][13] The third is an alternative version known as the Livre d'Artus (Book of Arthur), which too was written after the Vulgate Cycle had been completed but differs significantly from the mainstream version.

The Vulgate Merlin was reworked into multiple French and Italian works of verse and prose. Its English translations and adaptations include Henry Lovelich's poem Merlin, the Middle English anonymous Merlin, and the verse romance Of Arthour and of Merlin,[19] each based on different manuscripts of the Vulgate Merlin.[20]

Today, the Post-Vulgate Merlin is best known as the primary source of Malory for the first four books of Le Morte d'Arthur. It also served as the basis for the Merlin sections of the Castilian Demanda del Sancto Grial and Galician-Portuguese Demanda do Santa Graal.[2][16][21]

Prose Perceval

Merlin is believed to would have been followed by the third and final part of Robert's Grail cycle. However, such poem is either entirely lost or perhaps was never even really written. It is nevertheless uncertainly associated with the anonymous prose romance called the Prose Perceval (Perceval en prose), also known as the Didot Perceval after its better known manuscript.

Its first section, known as the Prologue, is considered to be rather the conclusion of Merlin.[22] The main part tells the story of Perceval's quest for and finding of the Grail. It is then followed by the section known as the Mort Artu, telling about the subsequent death of Arthur in battle against Mordred.

The Prose Perceval might be either a reworked prose 'translation' of Robert's poem or just another author's unofficial attempt to complete the trilogy while borrowing from Chrétien and others, and was found in only two of the many surviving manuscripts of the prose rendition of Merlin.[23][24] Patrick Moran made an argument that the entire Prose Perceval is not an autonomous text but rather an extension of Merlin, to which it is attached in both manuscripts (Didot and Modena) without any mark of passage from one text to another.[25]

See also

References

Bibliography

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.