Polanyi potential theory

Model of chemical adsorption From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In physical chemistry, the Polanyi potential theory, also called Polanyi's potential theory of adsorption or Eucken–Polanyi potential theory, is a model of adsorption proposed independently by Michael Polanyi and Arnold Eucken. Under this model, adsorption can be measured through the equilibrium between the chemical potential of a gas near the surface and the chemical potential of the gas from a large distance away.

In this model, the attraction largely due to Van der Waals forces of the gas to the surface is determined by the position of the gas particle from the surface, and that the gas behaves as an ideal gas until condensation where the gas exceeds its equilibrium vapor pressure. While the adsorption theory of William Henry is more applicable in low pressure and the adsorption isotherm equation from Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) theory is more useful at from 0.05 to 0.35 P/P0, the Polanyi potential theory has much more application at higher P/P0 (≈ 0.1–0.8).

History

Summarize

Perspective

In 1914, Arnold Eucken introduced his theory of adsorption and coined the term adsorption potential (German: Adsorptionspotential).[1][2][3] A few months, Michael Polanyi wrote his first paper on adsorption where he proposed a model for the adsorption of gas onto a solid surface.[1] Afterwards, he published a fully developed paper in 1916, which included experimental verification by his students and other authors. During his research in the University of Budapest, his mentor Georg Bredig, sent his research findings to Albert Einstein. Einstein wrote back to Bredig stating:

The papers of your M. Polanyi please me a lot. I have checked over the essentials in them and found them fundamentally correct.

Polanyi later described this event by saying:

Bang! I was a scientist.

Polanyi and Einstein continued to write to each other on and off for the next 20 years.

Criticism

Polanyi's model of adsorption was met with much criticism for several decades after publication years.

His simplistic model for determining adsorption was formed during the time of the discovery of Peter Debye's fixed dipoles, Niels Bohr's atomic model, and well as the developing theory of intermolecular forces and electrostatic forces by key figures in the chemistry world including W.H. Bragg, W.L. Bragg, and Willem Hendrik Keesom. Opponents of his model claimed that Polanyi's theory did not take into account these emerging theories. Criticism included that the model did not take into account the electrical interactions of the gas and the surface, and that the presence of other molecules would screen off the attraction of the gas to the surface. Polanyi's model was furthermore put under scrutiny following the adsorption model of Irving Langmuir from 1916 to 1918 through whose research would eventually win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1932. However, Polanyi was not able to participate in many of these discussions because he served as a medical officer for the Austro-Hungarian army in the Serbian front during World War I. Polanyi wrote about this experience saying:

I myself was protected for a while against any knowledge of these developments by serving as a medical officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army from August 1914 to October 1918, and by the subsequent revolutions and counter revolutions that lasted until the end of 1919. Members of less-well-informed circles elsewhere continued to be impressed for some time by the simplicity of my theory and its wide experimental verifications.[1]

Defense

Polanyi described that the “turning point” of the acceptance of his model of adsorption occurred when Fritz Haber asked him to defend his theory in full in the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry in Berlin, Germany. Many key players in the scientific world were present in this meeting including Einstein. After hearing Polanyi's full explanation of his model, Haber and Einstein claimed that Polanyi “had displayed a total disregard for the scientifically established structure of the matter”. Years later, Polanyi described his ordeal by concluding,

Professionally, I survived the occasion only by the skin of my teeth.

Polanyi continued to provide supporting evidence in proving the validity of his model years after this meeting.[1][non-primary source needed]

Refutation

Polanyi considered Eucken theory erroneous and claimed that Eucken modified his own theory in 1922 to fit with his.[1]

Polanyi's 'deliverance' (as he described it) from these rejections and criticism of his model occurred in 1930, when Fritz London proposed a new theory of cohesive forces founded on the theories of quantum mechanics on the polarization of electronic systems. Polanyi wrote to London asking,

“Are these forces subject to screening by intervening molecules? Would a solid acting by these forces possess a spatially fixed adsorption potential?”

After computational analysis, a joint publication was made between Polanyi and London claiming that the adsorptive forces behaved similarly to the model that Polanyi had proposed.[1]

Further research

Polanyi's theory has historical significance whose work has been used a foundation for other models, such as the theory of volume filling micropores (TVFM) and the Dubinin–Radushkevich theory. Other research have been performed loosely involving the potential theory of Polanyi such as the capillary condensation phenomenon discovered by Richard Adolf Zsigmondy. Unlike Poylani's theory which involves a flat surface, Zsigmondy's research involves a porous structure like silica materials. His research proved that condensation of vapors can occur in narrow pores below the standard saturated vapour pressure.[2]

Description

Summarize

Perspective

The Polanyi potential adsorption theory is based on the assumption that the molecules near a surface move according to a potential, similar to that of gravity or electric fields.[4] This model is applicable in the case of gases at a surface at constant temperature. Gas molecules move closer to that surface when the pressure is higher than the equilibrium vapor pressure. The change in potential relative to the distance from the surface can be calculated using the formula for difference of the chemical potential,

where is the chemical potential, is the molar entropy, is the molar volume, and is the molar internal energy.

At equilibrium, the chemical potential of a gas at a distance from a surface, , is equal to the chemical potential of the gas at an infinitely large distance from the surface, . As a result, the integration from an infinitely far distance to r distance from the surface leads to

where is the partial pressure at distance r and is the partial pressure at infinite distance from the surface.

Since the temperature remains constant, the difference in chemical potential formula can be integrated over pressures and

By setting the , the equation can be simplified to

Using the ideal gas law, , the following formula is obtained

Since gas condenses into a liquid on a surface when the pressure of the gas exceeds the equilibrium vapor pressure, , we can assume a liquid film forms over the surface of thickness, . The energy at is

Considering that the partial pressure of the gases relates to the concentration, the adsorption potential, can be calculated as

where is the saturated concentration of adsorbate and is the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate.

Derived theories

The potential theory underwent many refinements and changes throughout the years since its first report. One major theories of note that was developed using Polanyi's theory was the Dubinin theories, Dubinin–Radushkivech and Dubinin–Astakhov equations.

Using the adsorption potential, the degree of filling of the adsorption space, , can be calculated as

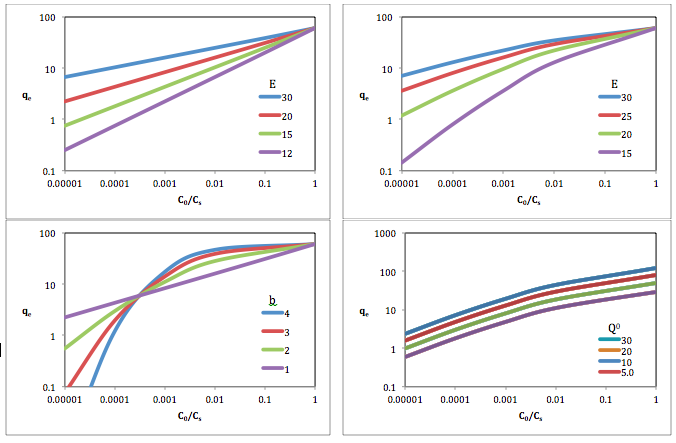

where is value of adsorption at temperature T and equilibrium pressure p, is the maximum value of adsorption, and is the characteristic energy of adsorption in kJ/mol, is the loss in Gibbs free energy in adsorption equal to and is the fitting coefficient.[5] The Dubinin–Radushkivech equation where is equal to 2 and the optimized Dubinin-Astakhov equation where is fit to experimental data can be simplified to

Top-left: Q0 = 60; b = 1

Top-right: Q0 = 60; b = 1.5

Bottom-left: Q0 = 60; E = 20

Bottom-right: E = 20; b = 1.5

Other studies have used the Dubinin–Astakhov in a similar form of ,

where is equilibrium adsorbed concentration of adsorbent in mg/g, is maximum adsorbed concentration of adsorbent in mg/g, is the effective adsorption potential, where equal to , is equilibrium concentration of adsorbent in the solution phase in mg/L, and is the adsorbent solubility in water in mg/L.[6]

The characteristic energy of adsorption can be related to a characteristic energy of adsorption for a standard vapor on the same surface, , through the use of an affinity coefficient,

The affinity coefficient is a ratio of the properties of the sample and standard vapors

where and are the polarizabilities of the sample and standard vapors, respectively. Many studies have been performed to determine optimal fitting coefficients, , and affinity coefficients, , to best describe the adsorption of gases and vapors onto solids. As a result, the Dubinin–Astakhov equation remains in use in adsorption studies due to the accuracy it can obtain when fitted with experimental results.

Dubinin–Astakhov parameters for vapors and gases

| Compound | Activated carbon | , kJ/mol | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzene | Carbon molecular sieve | 1.78 | 11.52 | 1.00 | [7] |

| Acetone | Carbon molecular sieve | 2.00 | 9.774 | 0.85 | [7] |

| Benzene | CAL AC | 2 | 18.23 | 1.00 | [8] |

| Acetone | CAL AC | 2 | 13.21 | 0.72 | [8] |

| Acetone | Carbon molecular sieve | 2.8 | 20.29 | 0.72 | [9] |

| Benzene | Carbon molecular sieve | 3.1 | 28.87 | 1.00 | [9] |

| Nitrogen | Carbon molecular sieve | 2.6 | 11.72 | 0.41 | [9] |

| Oxygen | Carbon molecular sieve | 2.3 | 9.21 | 0.32 | [9] |

| Hydrogen | Carbon molecular sieve | 2.5 | 5.44 | 0.19 | [9] |

Application

Summarize

Perspective

In many modern studies, the Polanyi theory is widely used in the study of activated carbons, or carbon black. The theory has been successfully used to model a variety of scenarios such as the gas adsorption on activated carbon and the adsorption process of nonionic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.[10] Later on, experiments also showed that it can model ionic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as phenols and anilines. More recently, the Polyani adsorption isotherm has been used to model to adsorption of carbon nanoparticles.

Characterization of carbon nanoparticles

Historically, the theory was used to model nonuniform adsorbates and multi-components solutes. For certain pairs of adsorbates and adsorbents, the mathematical parameters of the Polyani theory can be related to the physicochemical properties of both adsorbents and adsorbates. The theory has been used to model the adsorption of carbon nanotubes and carbon nanoparticles. In the study done by Yang and Xing,[6] the theory have been shown to better fit the adsorption isotherm than Langmuir, Freundlich, and partition. The experiment studied the adsorption of organic molecules on carbon nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes. According to the Polyani theory the surface defect curvatures of carbon nanoparticles could affect their adsorption. Flat surfaces on the particles will allow more surface atoms to approach adsorbing organic molecules which will increase the potential, leading to stronger interactions. The theory has been beneficial in trying to understand the adsorption mechanisms of organic compounds on carbon nanoparticles and estimating the adsorption capacity and affinity. Using this theory, researchers are hoping to be able to design carbon nanoparticles for specific needs such as using them as sorbents in environmental studies.

Adsorption from different systems

In one of the earlier studies conducted by Manes, M., & Hofer, L. J. E.,[11] the Polyani theory was used to characterize liquid-phase adsorption isotherms on various concentrations activated carbon using a wide range of organic solvent. The polyani theory was shown to be a good fit for these various systems. Because of the results, the study introduced the possibility of predicting isotherms for similar systems using minimal data. However, the limitation is that the adsorption isotherms for a large variety of solvents can only fit over a limited range. The curve was not able to fit the data at high-capacity range. The study also concluded that there were a few anomalies in the results. The adsorption from carbon tetrachloride, cyclohexane, and carbon disulfide onto activated carbon was not able to fit well to the curve, and remain to be explained. The researchers who conducted the experiment speculate that steric effects of carbon tetrachloride and cyclohexane may have played a role. The study has been done with a variety of systems such as organic liquids from water solutions and organic solids from water solutions.

Competitive adsorption

Since a variety of systems have been investigated, a study was done to investigate the individual adsorption of a mixed solution. This phenomenon is also called competitive adsorption because solutes tend to compete for the same adsorption sites. In the experiment conducted by Rosene and Manes,[12] the competitive adsorption of glucose, urea, benzoic acid, phthalide, and p-nitrophenol. Using the Polanyi adsorption model, they were able to calculate the relative adsorption of each compound onto the surface of activated carbon.

See also

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

...

...