Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas

Pontifical university in Rome, Italy From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas (PUST), also known as the Angelicum or Collegio Angelico (in honor of its patron, the Doctor Angelicus Thomas Aquinas), is a pontifical university located in the historic center of Rome, Italy. The Angelicum is administered by the Dominican Order and is the order's central locus of Thomistic theology and philosophy.

The Angelicum is coeducational and offers both undergraduate and graduate degrees in theology, philosophy, canon law, and social sciences, as well as certificates and diplomas in related areas. Courses are offered in Italian and some in English. The Angelicum is staffed by clergy and laity and serves both religious and lay students from around the world.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The Angelicum has its roots in the Dominican mission to study and to teach truth. This mission is reflected in the order's motto, "Veritas". The distinctively pedagogical character of the Dominican apostolate as intended by Saint Dominic de Guzman in 1214 at the birth of the order, "the first order instituted by the Church with an academic mission",[3] is succinctly expressed by another of the Order's mottos, contemplare et contemplata aliis tradere, (to contemplate and to bear the fruits of contemplation to others).[4] Pope Honorius III approved the Order of Preachers in December 1216 and January 1217.[5] On 21 January 1217 the papal bull Gratiarum omnium[6] confirmed the Order's pedagogical mission by granting its members the right to preach universally, a power formerly dependent on local episcopal authorization.[7]

Medieval origin (1222): the Santa Sabina studium conventuale

Saint Dominic established priories focused on study and preaching that became the Order's first studia generalia, at the Parisian convent of St. Jacques in 1217, at Bologna in 1218, at Palencia and Montpellier in 1220, and at Oxford before his death in 1221.[8] By 1219 Pope Honorius III had invited Dominic and companions to take up residence at the ancient Roman basilica of Santa Sabina, which they did by early 1220. In May 1220 at Bologna the Order's first General Chapter mandated that each convent of the Order maintain a studium.[9] The official foundation of the Dominican studium conventuale at Rome, which would grow into the Angelicum, occurred with the legal transfer of the Santa Sabina complex from Pope Honorius III to the Order of Preachers on 5 June 1222.[10]

St. Hyacinth of Poland and companions Bl. Ceslaus, Herman of Germany, and Henry of Moravia were among the first to study at the studium of Santa Sabina where "sacred studies flourished".[11]

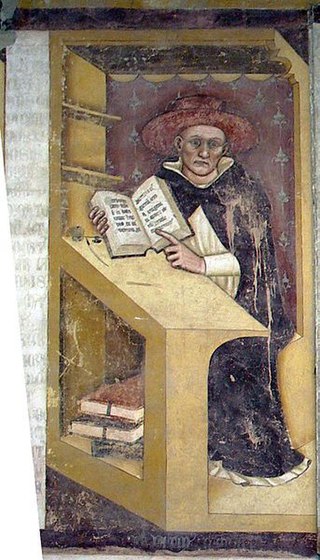

From its beginning the Santa Sabina studium played the special role of frequently providing papal theologians from among its members. Since its institution in 1218 the office of Master of the Sacred Palace has always been entrusted to a Friar of the Order of Preachers. In 1218 Saint Dominic was appointed as the first Master of the Sacred Palace by Pope Honorius III. In 1246 Pope Innocent IV appointed Annibaldo degli Annibaldi (c. 1220 – 1272) third Master of the Sacred Palace after Saint Dominic and Bartolomeo di Breganze. Annibaldi had completed his initial studies at the Santa Sabina studium conventuale and was later sent to the studium generale at Paris.[12] Aquinas dedicated to Annibaldi the Catena aurea, which he wrote during his regency at the Santa Sabina studium beginning in 1265.

1265: studium provinciale

At the general chapter of Valenciennes in 1259 Thomas Aquinas together with masters Bonushomo Britto, Florentius, Albert, and Peter took part in establishing a program of studies for novices and lectors including two years of philosophy, two years of fundamental theology, church history and canon law, and four years of theology. Those who showed capacity were sent on to a studium generale to complete this course becoming lector, magister studentium, baccalaureus, and magister theologiae.[13]

The new formation program outlined at Valenciennes featured the study of philosophy as an innovation. "In the early days there was no need to study philosophy or the arts in the Order; young men entered already trained in the humanities at the university. St. Albert received his arts training at Padua, St. Thomas at Naples; they were prepared to study theology. By 1259, however, it became evident that youths entering the Order were not sufficiently trained; the new ratio studiorum of 1259 established studia philosophiae in certain provinces corresponding to the university faculty of arts."[14]

In February 1265 newly elected Pope Clement IV summoned Aquinas to Rome as papal theologian.[15] That same year in accord with the injunction of the Chapter of the Roman province at Anagni, Aquinas was assigned as regent master at the studium at Santa Sabina:

We assign Friar Thomas of Aquino to Rome, for the remission of his sins, there to take over the direction of studies.[16]

With this assignment the studium at Santa Sabina, which had been founded in 1222, was transformed into the Order's first studium provinciale with courses under Aquinas' direction beginning 8 September 1265[17] and featuring studia philosophiae as prescribed by Aquinas and others at the 1259 chapter of Valenciennes.

This studium was an intermediate school between the studium conventuale and the studium generale. "Prior to this time the Roman Province had offered no specialized education of any sort, no arts, no philosophy; only simple convent schools, with their basic courses in theology for resident friars, were functioning in Tuscany and the meridionale during the first several decades of the order's life. But the new studium at Santa Sabina was to be a school for the province," a studium provinciale.[18] Tolomeo da Lucca, associate and early biographer of Aquinas, tells us that at Santa Sabina Aquinas taught the full range of philosophical subjects, "teaching in a new and special way almost the whole of philosophy, both moral and natural, but especially ethical and mathematical, as well as in writing and commentary."[19]

While Regent master at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale Aquinas began to compose his monumental work, the Summa theologiae, conceived of as a work suited to beginning students:

Because a doctor of catholic truth ought not only to teach the proficient, but to him pertains also to instruct beginners. as the Apostle says in 1 Corinthians 3: 1-2, as to infants in Christ, I gave you milk to drink, not meat, our proposed intention in this work is to convey those things that pertain to the Christian religion, in a way that is fitting to the instruction of beginners.[20]

At Santa Sabina Thomas composed the entire Prima Pars circulating it in Italy before departing for his second regency at Paris (1269–1272).[21]

Other works composed by Aquinas during this period at Santa Sabina include the Catena aurea in Marcum, the De rationibus fidei, the Catena aurea in Lucam, the Quaestiones disputate de potentia Dei, which report the disputations Aquinas held at Santa Sabina, the Quaestiones disputate de anima, which were held during the academic year 1265–66, Expositio et lectura super epistolas Pauli Apostoli, the Compendium theologiae, the Responsio de 108 articulis, part of the Quaestiones disputatae de malo, the Catena aurea in Ioannem, the De regno ad regem Cypri, the Quaestiones disputatae de spiritualibus creaturis, and at least the first book of the Sententia Libri De anima, a commentary on Aristotle's De anima. This work by Aristotle was contemporaneously being translated from the Greek by Aquinas' Dominican confrere William of Moerbeke at Viterbo in 1267.[22]

The so-called "lectura romana" or "alia lectura fratris Thome", a reportatio of the second commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard dictated by Aquinas at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale, may have been taken down by Jacob of Ranuccio while a student of Aquinas there from 1265 to 1268.[23] Jacob later was lector at Santa Sabina and served in the Roman Curia being made bishop in 1286, the year of his death.[24]

Nicholas Brunacci (1240–1322) was among Aquinas' students at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale and later at Paris. In November 1268 he accompanied Aquinas and his associate and secretary Reginald of Piperno from Viterbo to Paris to begin the academic year.[25] Albert the Great, Brunacci's teacher at Cologne after 1272, called him "the second Thomas Aquinas."[26] Brunacci became lector at the Santa Sabina studium and later served in the papal curia.[27] He was a correspondent by letter with Dante Alighieri during the latter's exile from Florence.[28]

1288: studium particularis theologiae, 1291 studium nove logice, 1305 studium naturarum

After the departure of Aquinas for Paris in 1268 other lectors at the Santa Sabina studium include Hugh Aycelin.[29] Eventually some of the pedagogical activities of the Santa Sabina studium were transferred to a new convent of the Order more centrally located at the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. This convent had a modest beginning in 1255 as a community for women converts, but grew rapidly in size and importance during its transfer to the Dominicans from 1265 to 1275.[30] In 1288 the theology component of the provincial curriculum was relocated from the Santa Sabina studium provinciale to the studium conventuale at Santa Maria sopra Minerva which was redesignated as a studium particularis theologiae.[31] During this period lectors at the Santa Maria sopra Minerva studium included Niccolò da Prato, Bartolomeo da San Concordio,[32] and Matteo Orsini.[33]

Following the curriculum of studies laid out in the capitular acts of 1291 the Santa Sabina studium was redesignated as one of three studia nove logice intended to offer courses of advanced logic covering the logica nova, the Aristotelian texts recovered in the West only in the second half of the 12th century, the Topics, Sophistical Refutations, and the First and Second Analytics of Aristotle. This was an advance over the logica antiqua, which treated the Isagoge of Porphyry, Divisions and Topics of Boethius, the Categories and On Interpretation of Aristotle, and the Summule logicales of Peter of Spain.[34] In 1305 the Minerva studium became one of four studia naturarum established in the Roman province.[35] Iacopo Passavanti, famed preacher and author of the Specchio di vera penitenza, was lector at the studium at Santa Maria sopra Minerva after finishing his studies in Paris c. 1333.[36]

1426: studium generale

The General Chapter of 1304 mandated each of the Order's provinces establish a studium generale to meet the demand of the Order's rapidly growing membership.[39] The studium at Santa Maria sopra Minerva was raised to the level of studium generale for the Roman province of the Order by the year 1426 and continued in this roll until 1539.[40] It would again be affirmed as a studium generale in 1694 (see below).

On 7 March 1457, the feast of St. Thomas, humanist Lorenzo Valla delivered the annual encomium in honor of the "angelic doctor." The Dominicans of the Minerva studium generale pressed Valla not only to praise Aquinas but to voice his humanist criticism of scholastic thomism.[41]

Sisto Fabri served as professor of theology at the Santa Maria sopra Minerva studium in the mid-1550s.[42] In 1585 Fabri, who was Master of the Order of Preachers from 1583 to 1598 would undertake a reformation of the program of studies for the Order and for the studium which had been transformed into the College of St. Thomas in 1577.[43] Fabri's reform included a nine-year formation program consisting of two years of logic using the Summulae logicales of Peter of Spain alongside Aristotle's logic, three years of philosophy including the study of Aristotle's De anima, Physica, and Metaphysica, and four years of theology using the third part of Aquinas' Summa for speculative theology, and the second part for moral theology.[44] Fabri also established a professorship for the study of Hebrew at the college.[43]

In 1570 the first edition of Aquinas' opera omnia, the so-called editio piana from Pius V the Dominican Pope who commissioned it, was produced there.[45]

Modern history (1577): Collegium Divi Thomae

The late sixteenth century saw the studium at Santa Maria sopra Minerva undergo further transformation during the pontificate of Pope Gregory XIII. Aquinas, who had been canonized in 1323 by Pope John XXII, was proclaimed fifth Latin Doctor of the Church by Pius V in 1567. To honor this great doctor, in 1577 Juan Solano, former bishop of Cusco, Peru, generously funded the reorganization of the studium at the convent of the Minerva on the model of the College of St. Gregory at Valladolid in his native Spain.[46] The features of this Spanish model included a fixed number of Dominican students admitted on the basis of intellectual merit, dedicated exclusively to study in virtue of numerous dispensations from other duties, and governed by an elected Rector.[47]

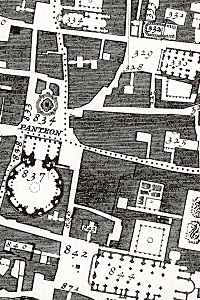

The result of Solano's initiative, which underwent further structural change shortly before Solano's death in 1580, was the Collegium Divi Thomae or College of St. Thomas. At the Minerva, the college occupied several existing convent structures as well as new constructions. A detail from the Nolli Map of 1748 gives some idea of the disposition of buildings when the Minerva convent housed the college.

The college cultivated the doctrines of St. Thomas Aquinas as a means of carrying out the Church's mission in the New World, where Solano had shown "much zeal in defending the rights of the Indians",[48] and where Dominicans like Bartolomé de las Casas, "Protector of the Indians", Pedro de Cordova, critic of the Encomienda system, and Francisco de Vitoria, theorist of international law, were already engaged.[49]

At the beginning of the seventeenth century several regents of the College of St. Thomas were involved in controversies over the nature of divine grace. Diego Alvarez (1550 c.-1635), author of the De auxiliis divinae gratiae et humani arbitrii viribus and famous apologist for the Thomistic doctrines of grace and predestination, was professor of theology at the college from 1596 to 1606.[50] Tomas de Lemos (Ribadavia 1540 – Rome 1629).[51] was professor of theology at the college in 1610. In the Molinist controversy between Dominicans and Jesuits the papal commission or Congregatio de Auxiliis summoned Lemos and Diego Alvarez to represent the Dominican Order in debates before Pope Clement VIII and Pope Paul V. Lemos was editor of the Acta omnium congregationum ac disputationum, etc. and author of the much discussed Panoplia gratiae (1676).[52] In 1608 Juan Gonzalez de Albelda, author of the Commentariorum & disputationum in primam partem Summa S. Thome de Aquino (1621) was regent of studies at the college.[53] In the 1620s Juan Gonzales de Leon was regent[54] Concerning the dispute on the nature of divine grace he took up an alternative doctrine within the Thomist school, that of Juan Gonzalez d'Albeda regent at the college in 1608, that "sufficient grace not only prepares the will for a perfect act [of contrition], but also gives the will an impulse towards that act. Yet due to man's defectability that impulse is always resisted."[55]

The college maintained the Dominican tradition of textual and linguistic activities as part of the Order's missionary dimension.[56] Like Moerbeke's translations of Aristotle in the 1260s and the editio piana of 1570 (see above), editorial and translation projects were undertaken by the college's professors, the most notable of which would be the leonine edition of Aquinas' works (see below). Vincenzo Candido (1573-1654) presided over the translation of the Bible into Arabic.[57] Candido had entered the Order at the convent of Santa Maria sopra Minerva completing there his novitiate and studies and becoming a doctor of theology,[58] and later rector of the college in 1630.[59] Candido also was part of the commission that concemned Jansenism. His own Disquisitionibus moralibus (1643) was later accused of laxims. Giuseppe Ciantes (d. 1670),[60] a leading Hebrew expert of his day and author of works such as the De sanctissima trinitate ex antiquorum Hebraeorum testimonijs euidenter comprobata (1667) and De Sanctissima incarnatione clarissimis Hebraeorum doctrinis...defensa (1667), completed his studies at the college was professor of theology and philosophy there before 1640. "In 1640 Ciantes was appointed by Pope Urban VIII to the mission of preaching to the Jews of Rome (Predicatore degli Ebrei) in order to promote their conversion." In the mid-1650s Ciantes wrote a "monumental bilingual edition of the first three Parts of Thomas Aquinas' Summa contra Gentiles, which includes the original Latin text and a Hebrew translation prepared by Ciantes, assisted by Jewish apostates, the Summa divi Thomae Aquinatis ordinis praedicatorum Contra Gentiles quam Hebraicè eloquitur.... Until the present this remains the only significant translation of a major Latin scholastic work in modern Hebrew."[61]

Tommaso Caccini (1574–1648), one of the principal critics of Galileo Galilei, was baccalaureaus at the college in 1615.[62]

Several figures associated with the college during this period were involved in the defense of the doctrine of Papal infallibility. Dominic Gravina, the most celebrated theologian of his day in Italy,[63] was professor of theology at the college in 1610.[51] Gravina was made master of sacred theology by the General Chapter of the Order at Rome in 1608. He wrote Vox turturis seu de florenti usque ad nostra tempora ... sacrarum Religionum statu (1625) in polemic with Robert Bellarmine whose De gemitu columbae (1620) criticized the decadence of religious orders.[64] Gravina, wrote concerning Papal infallibility: "To the Pontiff, as one (person) and alone, it was given to be the head;" and again, "The Roman Pontiff for the time being is one, therefore he alone has infallibility."[65]

In 1630 Abraham Bzovius funded a scholarship for Polish students at the college.[66]

Vicente Ferre (+1682), author of the Commentaria scholastica in Div. Thomam (1691) as well as of several commentaries on the Summa Theologica was regent of the college from 1654 to 1672. Ferre was recognized by his contemporaries as one of the leading Thomists of his day.[67] In his De Fide Ferre writes in defense of Papal infallibility that Christ said "I have prayed for thee, Peter; sufficiently showing that the infallibility was not promised to the Church as apart from (seorsum) the head, but promised to the head, that from him it should be derived to the Church."[68]

In the late seventeenth century figures such as Gregorio Selleri who taught at the college were instrumental in fostering the condemnation of Jansenism[69]

At the general chapter of Rome in 1694 Antonin Cloche, Master General of the Dominican Order, reaffirmed the College of St. Thomas as the studium generale of the Roman province of the Order.

We institute as a studium generale of this province...the Roman College of St. Thomas at our convent of Santa Maria sopra Minerva[70]

At this time, the college became an international centre of Thomistic specialization open to members of various provinces of the Dominican Order and to other ecclesiastical students, local and foreign.

In 1698, Cardinal Girolamo Casanata, Librarian of the Holy Roman Church, established the Biblioteca Casanatense at the Convent of Santa Maria sopra Minerva.[71] This library was independent of the College of St. Thomas, sponsoring its own Librarians. Casanate also endowed four chairs of learning at the college to foster the study of Greek, Hebrew and Dogmatic Theology.[72]

With the papal bull Pretiosus dated 26 May 1727[73] Dominican Pope Benedict XIII granted to all Dominicans major houses of study the right of conferring academic degrees in theology to students outside the Order.

In the 1748 General Chapter or the Order at Bologna it was stated that the Thomistic philosophical and theological tradition needed to be revived. In 1757 Master General Juan Tomás de Boxadors composed a letter to all members of the Order lamenting deviations from Thomistic doctrine, and demanded a return to the teachings of Aquinas. This letter was also published in the General Chapter Acts in Rome 1777. Responding to Boxadors and to the prevailing philosophical rationalism of the Enlightenment, Salvatore Roselli, professor of theology at the Roman College of St. Thomas,[74] published a six volume Summa philosophica (1777) giving an Aristotelian interpretation of Aquinas validating the senses as a source of knowledge.[75] While teaching at the college Roselli is considered to have laid the foundation for Neothomism in the nineteenth century.[76] According to historian J.A. Weisheipl in the late 18th and early 19th centuries "everyone who had anything to do with the revival of Thomism in Italy, Spain and France was directly influenced by Roselli's monumental work.[77]

After the Church's loss of the temporal power in 1870 the Italian government declared the college's vast library national property leaving the Dominicans in charge only until 1884.

Vincenzo Nardini (d. 1913) completed his theological and philosophical studies at the college and became lector there in 1855 teaching mathematics, experimental physics, chemistry and astronomy. Nardini reorganized the institute of science founded at the college in 1840 by Albert Gugliemotti. He believed the doctrines of Aquinas to be the only means to reconcile science and faith. Nardini was a founding member of the Accademia Romana di San Tommaso in 1879. Between 1901 and 1902 he also founded an astronomical observatory on via di Pie' di Marmo in Rome. In 1904 as Provincial of the Order's Roman province he proposed that the college be transformed into an international university. This was accomplished in 1908 by his successors.[78]

Gian Battista Embriaco (Ceriana 1829 – Rome 1903) taught at the college.[79] Embriaco was the inventor in 1867 of the hydrochronometer,[80] examples of which were built in Rome, first in the college's courtyard at the Minerva, and later on the Pincian Hill and in the Villa Borghese gardens.[81] Embriaco had presented two prototypes of his invention at the Paris Universal Exposition in 1867 winning prizes and acclaim.[82][better source needed][83]

The suppression of religious orders soon hampered the mission of the college. During the French occupation of Rome, from 1797 to 1814, the college was in declined and briefly closed its doors from 1810 to 1815.[84] The Order gained control of the convent once again in 1815.

By the late eighteenth century, professors of the college had begun to follow the Wolffianism and Eclecticism of Austrian Jesuit, Sigismund von Storchenau and Jaime Balmes with the aim of engaging modern thought. In response to this trend the General Chapter of 1838 again ordered the revival of Thomism and the use of the Summa Theologica at the College of St. Thomas.[85]

At the Minerva the Master of the Order issued a directive to re-establish the plan of study that had been in force before the French Revolution following the manual of Salvatore Roselli (1777–83) and prescribing a 5-year study of the Summa theologica for all degree candidates. The Minerva studium generale was refurbished, and a new era of Thomism was initiated led by Tommaso Maria Zigliara and others.[86]

After the Capture of Rome, the final act of the Risorgimento, the Dominicans were expropriated by the Italian government in virtue of law 1402 of 19 June 1873 and the Collegium Divi Thomae de Urbe was forced to leave the Minerva. The college continued its work at various locations in Rome.[87] Rector Zigliara, who taught at the college from 1870 to 1879, with his professors and students took refuge with the Fathers of the Holy Ghost at the French College in Rome, where lectures continued.[88] In 1899 the college was functioning in the Palazzo Sinibaldi, adjacent to the French College and near the Convent of the Minerva.[89]

Zigliara was a member of seven Roman congregations, including the Congregation of Studies and was a founding member of the Accademia Romana di San Tommaso in 1879. Zigliara's fame as a scholar at the forefront of the Neo-Thomist revival was widespread in Rome and abroad. "French, Italian, German, English, and American bishops were eager to put some of their most promising students and young professors under his tuition."[88]

The mid-19th-century revival of Thomism, sometimes called "Neo-Scholasticism" or "Neo-Thomism," had its origins in Italy. "The direct initiator of the neo-Scholastic movement in Italy was Gaetano Sanseverino, (1811–1865), a canon at Naples."[90] Other prominent figures include Zigliara, Josef Kleutgen, and Giovanni Cornoldi. The revival emphasizes the interpretative tradition of Aquinas' great commentators such as Capréolus, Cajetan, and John of St. Thomas. Its focus, however, is less exegetical and more concerned with carrying out the program of deploying a rigorously worked out system of Thomistic metaphysics in a wholesale critique of modern philosophy. Zigliara was instrumental in recovering the authentic tradition of Thomism from the influence of a tradition of the Jesuits' that was "strongly colored by the interpretation of their own great master Francisco Suárez (d. 1617), who had attempted to reconcile the Aristotelianism of Thomas with the Platonism of Scotus" [91]

In response to the disarray of religious educational institutions Pope Leo XIII in his encyclical Aeterni Patris of 4 August 1879 called for the renewal of Christian philosophy and particularly the doctrines of Aquinas:

We exhort you, venerable brethren, in all earnestness to restore the golden wisdom of St. Thomas, and to spread it far and wide for the defense and beauty of the Catholic faith, for the good of society, and for the advantage of all the sciences.[92]

Pope Leo XIII's encyclical Aeterni Patris of 1879 was a great impetus to the revival of neo scholastic Thomism. On 15 October 1879 Leo created the Pontifical Academy of St. Thomas Aquinas and ordered publication of a critical edition of the complete works of the doctor angelicus. Superintendence of the "leonine edition" was entrusted to Zigliara. Leo also founded the Angelicum's Faculty of Philosophy in 1882 and its Faculty of Canon Law in 1896. The college began once again to gain status and influence. Under Pope Leo XIII Zigliara contributed to the encyclicals Aeterni Patris and Rerum novarum.[93]

1906: Pontificium Collegium Divi Thomae de Urbe

In response to the call for a renewal of Thomism sounded by Aeterni Patris rectors Tommaso Maria Zigliara (1833–1893), Alberto Lepidi (1838–1922), and Sadoc Szabó had brought the college to a high degree of excellence. Under the leadership of Szabó the number of subjects taught at the Angelicum included archeology, geology, paleography, Christian art, biology, mathematics, physics, and astronomy.[94]

At the dawn of the twentieth century the Dominican conception of intellectual formation at Rome was again transformed. The general chapters of 1895 (Avila) and 1901 (Ghent) had called for the expansion of the College of St. Thomas to meet the growing educational needs in the modern world. The Chapter of 1904 (Viterbo) directed Hyacinthe-Marie Cormier (1832–1916), newly elected Master General of the Order of Preachers, to develop the college into a studium generalissimum directly under his authority for the entire Dominican Order:

Romae erigatur collegium studiorum Ordinis generalissimum, auctoritate magistri generalis immediate subjectum, in quo floreat vita regularis, et ad quod mittantur fratres ex omnibus provinciis.[95]

Building on the legacy of the Order's first Roman studium at the priory of Santa Sabina founded in 1222 and the studium general that had sprung from it by 1426 at Santa Maria sopra Minerva and that in 1577 became the College of Saint Thomas, Cormier stated his intention to establish this new studium generalissimum as the principal vehicle of dissemination of orthodox Thomistic thought for both Dominicans and secular clergy.

In 1904 Pope Pius X allowed diocesan seminarians to attend the college. He elevated the college to the status of Pontificium on 2 May 1906, making its degrees equivalent to those of the world's other pontifical universities.[96] By Apostolic Letter of 8 November 1908, signed on 17 November, the Pope transformed the college into the Collegium Pontificium Internationale Angelicum, located on Via San Vitale 15. Cormier developed the Angelicum until his death in 1916, establishing it principal guidelines,[97] giving it his motto as Master General, caritas veritatis, "the charity of truth."[98] Cormier, also noted for the spiritual quality of his retreats and powerful preaching, was declared Blessed by Pope John Paul II on 20 November 1994.

In the first half of the twentieth century Angelicum professors Édouard Hugon, Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange and others carried on Leo's call for a Thomist revival. The core philosophical commitments of the revival, which after Zigliara traditionally are those of the Angelicum, were later summarized in "Twenty-Four Thomistic Theses" approved by Pope Pius X.[99] Due to its rejection of attempts to synthesize Thomism with non-Thomistic categories and assumptions neo-scholastic Thomism has sometimes been called "Strict Observance Thomism."[100]

In 1909 there were 26 professors. Beyond philosophy and theology subject included archeology, geology, paleography, Christian art, biology, mathematics, physics, and astronomy. In 1917 a professorship in ascetical and mystical theology was created at the Angelicum expressly for Fr. Garrigou-Lagrange. This was the first of its kind in the world, and Garrigou-Lagrange initiated courses in sacred art, mysticism, and aesthetics in 1918.[101] Marie-Alain Couturier studied with Garrigou at the Angelicum from 1930 to 1932 before going on to have an instrumental role in liturgical art ventures such as Henri Matisse's Vence Chapel and Le Corbusier's Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut, and the Dominican priory of Sainte Marie de La Tourette.[102]

Garrigou-Lagrange has been called "torchbearer of orthodox Thomism" against Modernism in the period between World War II and the Cold War.[103] He is commonly held to have influenced the decision in 1942 to place the privately circulated book Une école de théologie: le Saulchoir (Étiolles 1937) by Marie-Dominique Chenu on the Vatican's "Index of Forbidden Books" as the culmination of a polemic within the Dominican Order between the Angelicum supporters of a speculative scholasticism and the French revival Thomists who were more attentive to historical hermeneutics, such as Yves Congar. Congar's Chrétiens désunis was also suspected of modernism because its methodology derived more from religious experience than from syllogistic analysis.[104]

Noted philosopher and theologian Santiago Maria Ramirez y Ruiz de Dulanto (1891–1967) completed his licentiate and doctorate in philosophy at the Angelicum from 1913 to 1917 with a dissertation entitled De quidditate Incarnationis, becoming lector on 27 June 1917 and teaching there from 1917 to 1920.[105] Ramirez relates that he was fortunate during his student years to hear Pope Pius X deliver a talk to the professors and students at the Angelicum on 28 June 1914 in which the Pontiff extolled Aquinas' doctrines above those of all others,[106] and another talk delivered by Pope Pius XI at the Angelicum on 12 December 1924 in which he reaffirmed the doctrinal authority of St. Thomas Aquinas.[107]

29 June 1923 on the occasion of the sixth centenary of the canonization of Thomas Aquinas Pius XI's encyclical Studiorum ducem singled out the Pontifical Angelicum College as the official sedes Thomae:

It will be fitting...that the institutes where sacred studies are cultivated express their holy joy, before all the Pontifical Angelicum College where Thomas could be said to dwell in his own house, and then all the other ecclesiastical schools that are in Rome.[108]

The reputation of the college during this period was summed up by one of the Angelicum's most illustrious alumni and faculty members in the mid-twentieth century, Cornelio Fabro, who called the Angelicum the "avant-garde of the doctrinal mission of the Dominican Order in Rome, and of traditional Thomism whose distinguished exponents included T. Zigliara, A. Lepidi, T. Pègues, E. Hugon, A. Zacchi, R. Garrigou-Lagrange, and M. Cordovani."[109] The notoriety of the college was further fostered by annual celebrations of the Feast of its patron St. Thomas Aquinas including a "preaching tridiuum", a pontifical Mass and an academic symposium at the Angelicum[110] 8 June 1923 Szabó founded Unio thomistica, an association of Angelicum students and alumni dedicated to defense of Thomistic doctrine. Its publication originally entitled Unio thomistica would continue under the title Angelicum, a trimesterly journal with articles in Italian, French, English, German, and Spanish treating theology, philosophy, canon law, and social sciences.[111]

The year 1926 saw the Angelicum become an institute with its change of name to Pontificium Institutum Internationale Angelicum. During the academic year 1927–28 Angelicum professor Mariano Cordovani began a Philosophy Circle that continued into the 1960s as a forum for laity to explore contemporary philosophical issues.[112]

In 1927 the Italian government decided to sell the former convent of Santi Domenico e Sisto. The convent, which had been established by Pope Pius V for Dominican nuns in 1575, was expropriated by the Italian government on 9 September 1871 in virtue of the law of suppression of religious orders. Blessed Buenaventura García de Paredes, Master General of the Order, seeing the opportunity to recuperate the Dominican patrimony, suggested to Benito Mussolini that selling the convent to the Order would return the property to its original owners, and that it could be used to house the Angelicum[113]

By decree of 2 June 1928 the Italian Minister of Justice authorized the College of St. Thomas to purchase from the Italian State for the agreed price of nine million lire (L. 9,000,000) the complex of buildings constituting the former convent of Saints Dominic and Sixtus [114] In this way Paredes activated Cormier's plan for the Angelicum to be established at a site whose amplitude was more fitting to its new status.

In 1930 Étienne Gilson and Jacques Maritain were the first two philosophers to receive honorary doctorates from the Angelicum.[115]

For the academic year 1928–1929 Paredes celebrated the inaugural Mass in the Church of Saints Dominic and Sixtus and Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange gave the solemn inaugural lecture.[116] Because the convent buildings required extensive renovation classes were not held there until 1932.

From 1928 to 1932 the convent was renovated to house classrooms, an aula magna and an aula minor, amphitheaters with seating capacities of 1,100 and 350 respectively. In November 1932 the Angelicum opened its doors at the appropriately more extensive complex of buildings comprising the ancient Dominican convent of Saints Dominic and Sixtus.

Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli the future Pope Pius XII gave a lecture at the college entitled "La Presse et L'Apostolat" on 17 April 1936.[117]

The Angelicum changed names once again in 1942 becoming the Pontificium Athenaeum Internationale Angelicum.

In 1951 the Institute of Social Sciences was founded within the Faculty of Philosophy by Raimondo Spiazzi (1918–2002). Spiazzi, a prolific author and editor of the works of Aquinas, completed his doctorate in Sacred Theology at the Angelicum in 1947 with a dissertation entitled "Il cristianesimo perfezione dell'uomo. Spiazzi directed the Institute of Social Sciences until 1957 and continued teaching there until 1972.[118] This Institute was established as the Faculty Faculty of Social Sciences (FASS) in 1974. Mieczysław Albert Krąpiec, leading exponent of the Lublin School of Philosophy in Poland, received a doctorate in theology from the Angelicum in 1948.[119]

In 1950 the Angelicum's Institute of Spirituality was founded by Paul-Pierre Philippe within the Faculty of Theology to promote scientific and systematic study of ascetical and mystical theology, and to offer preparation for spiritual directors. The institute was approved by the Congregation for Catholic Education on 1 May 1958.[120] The poet Paul Murray was director,[121] followed by Michael Sherwin, OP, professor of Moral Theology at the Angelicum.

1963: Pontificia Studiorum Universitas a Sancto Thoma Aquinate in Urbe

Enrollment climbed from 120 in 1909 to over 1,000 during the 1960s.[122] During the tenure of Aniceto Fernández as Master of the Order of Preachers (1962–1974)[123] and the rectorate of Raymond Sigmond (1961–1964)[124] Pope John XXIII visited the Angelicum[125] on 7 March 1963, the feast of the university's patron Saint Thomas Aquinas and with the motu proprio Dominicanus Ordo,[126] raised the Angelicum to the rank of pontifical university. Thereafter it would be known as the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas in the city (Latin: Pontificia Studiorum Universitas a Sancto Thoma Aquinate in Urbe).[127]

On 29 November 1963, Egyptian scholar and peritus at Vatican II for Christian–Islamic relations Georges Anawati delivered a lecture entitled at the Angelicum "L'Islam a l'heure du Concile: prolegomenes a un dialogue islamo-chretien." [128]

On 19 April 1974 Pope Paul VI delivered an allocution in the Angelicum's Aula Magna as part of the International Congress of the International Society of St. Thomas Aquinas celebrated on the occasion of the seventh centenary of the death of the Doctor Angelicus. The Pontif described Aquinas as a teacher of the art of thinking well and expounded his doctrine proposing Aquinas as an unsurpassed master.[129]

On 17 November 1979, one year into his papacy, Pope John Paul II visited his alma mater to deliver an address marking the first centenary of the encyclical Aeterni Patris. The Pontiff reaffirmed the centrality of Aquinas' thought for the Church and the unique role of the Angelicum, where Aquinas is "as in his own home (tamquam in domo sua)," in carrying on the Thomist philosophical and theological tradition.[130]

On 24 November 1994, four days after beatifying Hyacinthe-Marie Cormier, Pope John Paul II visited the Angelicum and gave an address to faculty and students on the occasion of the dedication of the university's Aula Magna in his honor.[131]

On 18 May 2020, the 100th anniversary of the birth of Pope John Paul II the St. John Paul II Institute of Culture was established within the Faculty of Philosophy. The Institute was founded thanks to the support of private donors. It carries out several research, academic, educational and cultural projects to deepen knowledge of the intellectual and spiritual heritage of the pope and foster understanding of key problems facing the Church and the world today, in the light of his teaching. The Institute offers the JP2 Studies program – a one-year, interdisciplinary diploma for clergy, religious and laity. The professors teaching at the JP2 Studies program are, i.e.: Helen Alford, O.P., George Weigel, Jarosław Kupczak, O.P., Rémi Brague.

The Angelicum today

Today the faculty and students of the Angelicum strive to be "modern disciples of Thomas Aquinas", "accepting all the radical changes" of the modern world "but without compromise" to the ideals of their patron Thomas Aquinas.[132] Angelicum alumnus and famed historian and philosopher James A. Weisheipl notes that since the time of Aquinas "Thomism was always alive in the Dominican Order, small as it was after the ravages of the Reformation, the French Revolution, and the Napoleonic occupation."[133] While outside the order Thomism has had varying fortunes, the Angelicum has played a central role throughout its history in preserving Thomism since the time of Aquinas' own activity at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale. Today the sedes Thomae continues to provide students and scholars with the opportunity to immerse themselves in the authentic Dominican Thomistic philosophical and theological tradition.

As of August 2014 the student body comprised approximately 1010 students coming from 95 countries. About one half of the Angelicum's students are enrolled in the faculty of theology.

As of August 2014 the student body consisted of approximately 29% women, 71% men. Of these, approximately 24% were lay, 27% were diocesan clerical, and 49% were members of religious orders. Moreover, 30% of the student body hailed from North America, 25% from Europe, 21% from Asia, 12% from Africa, 11% from Latin America, and 1% from Oceania.[134]

Some comparatively recent notable figures associated with the Angelicum include Cornelio Fabro, Jordan Aumann, Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, Aidan Nichols, Wojciech Giertych, Theologian of the Pontifical Household under Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis, and Bishop Charles Morerod, past Rector Magnificus of the Angelicum and former Secretary of the International Theological Commission, Alejandro Crosthwaite, OP, Dean of the Angelicum Faculty of Social Sciences, and Consultant to the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, and Robert Christian, Vice-Dean of the faculty of theology, professor of sacramental theology and ecclesiology, and Consultant to the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. Dr. Donna Orsuto, professor of spirituality, is rector of the Lay Centre at Foyer Unitas and was recently created a Dame of the Order of St. Gregory the Great by Pope Benedict.

Remove ads

Academics

Summarize

Perspective

Quality and ranking

The Angelicum is one of the world's Pontifical universities. Specifically, a pontifical university addresses "Christian revelation and disciplines correlative to the evangelical mission of the Church as set out in the apostolic constitution, Sapientia christiana".[135][136]

In distinction to secular or other Catholic universities, which address a broad range of disciplines, Ecclesiastical or Pontifical universities are "usually composed of three principal ecclesiastical faculties, theology, philosophy, and canon law, and at least one other faculty". Current international quality ranking services do not have rankings for pontifical universities that are specific to their curricula.

Since 19 September 2003 the Holy See has taken part in the Bologna Process, a series of meetings and agreements between European states designed to foster comparable quality standards in higher education, and in the "Bologna Follow-up Group".[137][138][139]

The Holy See's Agency for the Evaluation and Promotion of Quality in Ecclesiastical Universities and Faculties (AVEPRO) was established on 19 September 2007 by the Pope Benedict XVI "to promote and develop a culture of quality within the academic institutions that depend directly on the Holy See and ensure they possess internationally valid quality criteria."[136]

Academic authorities

- Grand Chancellor, the Master General of the Order of Preachers. On 13 July 2019, Fr. Gerard Francisco Timoner III was elected the 88th Master General of the Order of Preachers at the 291st General Chapter, held in Biên Hòa.[140]

- Rector Magnificus. Thomas Joseph White was appointed rector on 10 June 2021. He is the first American to serve in this office.[141]

- Vice-Rector

- Deans of the Faculties

- Heads of the Institutes

- Administrator

- Secretary General

- Public Relations Officer

- Prefect of the Library

- University Chaplain

Faculties and degrees

In addition to the programs listed, which are in the Italian language, the Angelicum offers English programs in Philosophy and Theology for the first cycle, and part of the second and third cycles.[142]

Theology[143]

- First Cycle: Baccalaureate in Sacred Theology, Sacrae Theologiae Baccalaureatus (S.T.B.)

- Second Cycle: Licentiate in Sacred Theology, Sacrae Theologiae Licentiatus (S.T.L.)

- Third Cycle: Doctorate in Sacred Theology, Sacrae Theologiae Doctoratus (S.T.D.)

Sections:

- Biblical

- Dogmatic

- Moral

- Thomistic

- Spirituality

- Ecumenism: The Angelicum is the only Pontifical university in Rome granted the right to offer advanced theology degrees in ecumenism. The Angelicum offers the licentiate degree in theology with a specialization in ecumenical studies.

Chairs of Learning:[143]

- The J.-M. Tillard Chair of Ecumenical Studies: The Tillard Chair was dedicated 25 February 2003 in honor of Dominican Jean-Marie Tillard,[144] one of the greatest exponents of post-conciliar ecumenical movement. Tillard studied philosophy at the Angelicum from 1952 to 1953 obtaining the doctorate degree with a thesis entitled Le bonheur selon la conception de saint Thomas d'Aquin.[145] At Vatican II, Tillard served as a "peritus" for the Canadian bishops, and subsequently became a consultant to the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity.

- The Non-Conventional Religions and Spiritualities Chair (RSNC) which promotes the study of modern and contemporary religious phenomena

Canon Law[146]

- First Cycle: Baccalaureate in Canon Law, Juris Canonici Baccalaureatus (J.C.B.)

- Second Cycle: Licentiate in Canon Law, Iuris Canonici Licentiatus (J.C.L.)

- Third Cycle: Doctorate in Canon Law, Iuris Canonici Doctoratus (J.C.D.)

Philosophy[147]

- First Cycle: Baccalaureate in Philosophy, Philosophiae Baccalaureatus (Ph.B.)

- Second Cycle: Licentiate in Philosophy, Philosophiae Licentiatus (Ph.L.)

- Third Cycle: Doctorate in Philosophy, Philosophiae Doctoratus (Ph.D.)

Social Sciences[148]

- First Cycle: Baccalaureate in Social Sciences, Scientiarum Socialium Baccalaureatus

- Second Cycle: Licentiate in Social Sciences, Scientiarum Socialium Licentiatus

- Third Cycle: Doctorate in Social Sciences, Scientiarum Socialium Doctoratus

Chairs of Learning:

- The Cardinal Pavan Chair for Social Ethics: The Pavan Chair was established in honor of Italian Cardinal Pietro Pavan[149][better source needed] to promote interdisciplinary research on social issues and problems especially in the realm of ethics and development of the social teaching of the Church.[150] Pavan was an expert on Catholic social teaching. He collaborated with Pope John XXIII especially on the encyclical Pacem in Terris. The "Cardinal Pavan Chair for Social Ethics" was launched as part of the Angelicum 50th anniversary celebrations and to mark the 40th anniversary of the publication of Pacem in Terris.[151]

Aggregated institutions

- Sacred Heart Major Seminary, Detroit (USA)[152]

Affiliated institutions

- Blackfriars Studium, Oxford (England)[153]

- Collegio Alberoni, Piacenza (Italy)[154]

- St. Charles Seminary, Nagpur (India)[155]

- St. Mary's Priory, Dominican House of Studies, Tallaght (Ireland)[156]

- St. Saviour’s Priory, Dublin (Ireland), Dominican House of Studies – Studium, since 2000.[157]

- St. Joseph's Seminary (Dunwoodie), New York (USA)[158]

- Istituto Teologico De America Central Intercongregacional, S. Jose (Costa Rica)

- Sacred Heart Institute, Gozo (Malta)

- Dominican Institute, Ibadan (Nigeria)[159]

- Centro de Estudio de los Dominicanos del Caribe, Bayamon (Puerto Rico)

- Studio Filosofico Domenicano, Bologna (Italy)[160] (in Italian)

- Escola Dominicana de Teologia, Alto do Ipiranga, São Paulo (Brazil)[161] (in Portuguese)

- Centro de Teologia Santo Domingo de Guzman, St. Domingo (Dominican Republic)

- Saint John Seminary, Boston, MA (USA)

Sponsored institutes

Associated institutions

Related programs

- Science, Theology and the Ontological Quest[169]

- Bridge Builder Project [170]

- Center for Catholic Studies, University of St. Thomas (Minnesota)[171]

- Religions and Non-conventional Spiritualities Chair (RNCS)[172]

- Ethical Leadership International Program[173]

- Management and Corporate Social Responsibility[174] (in Italian)

- Management of the Organizations of the Third Sector[175] (in Italian)

- The John Paul II Center for Interreligious Dialogue,[176] a partnership between The Russell Berrie Foundation and the Angelicum, aims to build bridges between diverse religious traditions. The Center features top-level visiting faculty teaching interreligious dialogue courses, and the prestigious John Paul II Lecture on Interreligious Understanding.[177]

Scholarships

The Russell Berrie Fellowship in Interreligious Studies[178] targets members of the laity and clergy for the purpose of studying at the Angelicum to obtain License or Doctoral Degrees in Theology with a concentration in Inter-religious Studies. The goal of the Fellowship Program is to build bridges between Christian, Jewish, and other religious traditions by providing the next generation of religious leaders with a comprehensive understanding of and dedication to interfaith issues. The award will provide one year of financial support the Russell Berrie Foundation,[179] which carries on the values and passions of the late Russell Berrie,[180] by promoting the continuity of the Jewish tradition, and fostering religious understanding and pluralism. Financial support is intended to cover tuition, a living stipend, examination fees, a book allowance, and travel expenses to and from the recipient's home country once a year.

The William E. Simon Scholarship Fund provides financial assistance for academically qualified students who live in Rome and who would otherwise lack the resources to cover their educational expenses at the Angelicum. Each scholarship award provides no more than 40% of the total annual expense of tuition, room, board, and related fees and expenses. Annually the fund allocates 50% of its scholarships for lay students.[181]

International Dominican Foundation[182] (IDF) is a non-profit organization that provides monetary support to Dominican educational programs at the Jerusalem École Biblique, the Angelicum in Rome, and the Dominican Institute for Oriental Studies (IDEO)in Cairo.[183] The IDF made grants of approximately $270,000.00 for the academic year 2011–2012, the major part of which went the Angelicum in accord with the William E. Simon Scholarship, the McCadden-McQuirk Foundation, and the Réginald de Rocquois Foundation.[184]

United States Federal Loan Program

The Angelicum is listed under schools in Rome that can participate in the US Federal Loan Program.[185][186]

Academic calendar

The regular academic year at the Angelicum runs from early October until the end of May. Some of the university's important annual events are as follows:

October Solemn Inauguration of the Academic Year and Mass of the Holy Spirit

22 October Solemnity of the Dedication of the Church of Saints Dominic and Sixtus

15 November Feast of Saint Albert the Great.

7 March Feast of the university's patron Saint Thomas Aquinas

21 May Solemn Mass for the Ending of the Academic Year and Conferral of academic degrees. Dominican feast of Bl. Hyacinthe-Marie Cormier

June A summer session runs for the month of June.

Generally administration offices remain open until the end of July, are closed for the month of August, and reopen in early September.

Remove ads

Angelicum campus

Summarize

Perspective

The Angelicum campus is located in the historic center of Rome, Italy, on the Quirinal Hill in the section or rione of the eternal city known as Monti. It is situated near the beginning of via Nazionale just above the ruins of Trajan's Market, the via dei Fori Imperiali, and Piazza Venezia.

Site

The site of the Angelicum is recorded in history sometime before the year 1000 bearing the name Magnanapoli with a church dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary. The nature of the site before the ninth century is uncertain. One theory holds that its name Magnanapoli derives from the expression Bannum Nea Polis or "fort of the new city" from the adjacent Byzantine military citadel which included the Torre delle Milizie Rome's oldest extant tower.[187]

Architectonic features

In 1569 Dominican Pope Pius V ordered the construction of the Church of Saints Dominic and Sixtus. This was followed in 1575 by a convent for Dominican nuns. Among the architects who worked on the complex are Vignola; Giacomo della Porta; Nicola and Orazio Torriani; and Vincenzo della Greca. The church's double staircase was added in 1654 by sculptor architect Orazio Torriani.

In 1870 the religious community was expropriated by the Italian government. The Order was able to reacquire the complex in 1927 from the Italian government. After extensive renovation and additions the Angelicum and a convent of Dominican Friars was installed there. Today the university occupies approximately the entire ground level of the complex. The remaining portion, approximately the second and third levels around the cloister together with subterranean spaces, constitutes a convent for the community of Dominican Friars that serves the university.

The main entrance of the Angelicum immediately to the right of the Church of Saints Dominic and Sixtus was built into the existing structure in the early 1930s as part of the renovations undertaken to accommodate the Angelicum at its new site. A wide flight of stairs leads to a Palladian motif portico above which are mounted a Dominican shield bearing one of the Order's mottos "laudare, benedicere, praedicare" (to praise, bless, and preach) on the right, and the escutcheons of Pope Pius XI[188] who was reigning when the Pontificium Institutum Internationale Angelicum opened its doors in 1932, on the left. The main entrance of the Angelicum was used in 2010 as a location in the film "Manuale d'amore 3". part of a 4 movie romantic comedy, directed by Giovanni Veronesi and starring Robert De Niro, and Monica Bellucci who were on campus shooting the film.[189]

Under the entrance portico are two statues c. 1910 by sculptor Cesare Aureli (1843-1923) of St Albert the Great[190] on the left and St. Thomas Aquinas on the right. The base of the statue of Aquinas bears an inscription attributed to Pope Pius XI, "Sanctus Thomas Doctor angelicus hic tamquam domi suae habitat," (Saint Thomas the Angelic Doctor dwells here as in his own house), a paraphrase of the papal encyclical Studiorum ducem that singles out the Angelicum as the preeminent Thomistic center of learning: "ante omnia Pontificium Collegium Angelicum, ubi Thomam tamquam domi suae habitare dixeris".[191]

The Angelicum's statue of Aquinas is Aureli's second version of this work. The first version of 1889[192] looms majestically over the Sala di Consultazione or main reference room of the Vatican Library.[193] At the instigation of the Pontifical Roman Seminary the Vatican version of the statue was commissioned in the name of all seminaries of the world as a gift to Pope Leo XIII in celebration of his episcopal jubilee in 1893.[194][195] The statue has been described in the following terms:

St. Thomas seated, in his left arm holds the Summa theologica while extending his right arm in the act of protecting Christian science. Thus, he does not sit on the cathedra of a doctor but on the throne of a sovereign protector; he extends his arm to reassure, not to demonstrate. He wears on his head the doctoral birettum of the traditional type which reveals the face and expression of a profoundly educated person.... The immortal book that he clutches, the powerful arm that extends to affirm sacred science and to halt the audacity of error, are truly grand, and in the words of Leo XIII, have equaled the genius of all other great teachers.[196]

On the occasion of the blessing of this statue in 1914 Hyacinthe-Marie Cormier delivered his "Sed Contra: Allocution aux novices étudiants du Collège Angélique pour la bénédiction d'une statue de S. Thomas d'Aquin dans leur oratoire."[197]

The Angelicum cloister

A central cloister with garden and fountain forms the heart of campus. The two basins of the ancient fountain are fed by the Acqua Felice aqueduct, one of the aqueducts of Rome, and the first new aqueduct of early modern Rome, completed in 1585 by Pope Sixtus V[199] whose birth name was Felice Peretti. It also feeds the fountain by Giovanni Battista Soria (c. 1630) at the entrance to the Angelicum's walled garden, and the fountain under the stair below the university's portineria or porter's lodge before coursing across the Quirinal Hill to its terminus at the Moses fountain or Fontana dell'Acqua Felice on the Via del Quirinale.[200]

Arched porticos designed by Vignola but completed after his death flank the cloister. Ten arches on the long sides and seven on the short are sustained by pilasters in the Tuscan style rising from high plinths. A simple frieze with smooth triglyphs and metopes separates lower from upper levels.

Eleven classrooms encircle the cloister, the last of which, the Aula della Sapienza (Hall of Wisdom) is the site of the university's doctoral defenses. Also located off the cloister are the administration offices and the Sala delle Colonne, a reception room with antique marble columns and arched ceilings bearing traces of late Renaissance style frescos, which initially housed a library.

On the second level encircling the cloister are the living quarters of Dominican professors and the Sala del Senato (Academic Senate Room). The latter was the Chapter room of the convent and is appointed with a 14th-century triptych of Saint Andrew by Lippo Vanni,[201] a 13th-century crucifix, and a full-body relic of an unidentified saint encased in Imperial Roman armor.[202]

The Angelicum auditoria

To the east of the Sala delle Colonne is the Aula Magna Giovanni Paolo II, a raked semicircular auditorium with seating for 1100 people that was constructed during 1930s renovations by Roman engineer Vincenzo Passarelli (1904–1985).[203] The Aula Magna was recently renamed after one of the Angelicum's most illustrious alumni, Pope John Paul II. The adjacent Aula Minor San Raimondo seats 350 people. Beyond these auditoria are the university's cafe, the Angelicum Bookshop, and the university's library.

The Angelicum administration building

The Palazzo dei Decanati (Deans' Building) is located at the West edge of campus just inside the main gates. The West boundary of the Angelicum is formed by the Salita del Grillo.

The Angelicum library

The main part of the Angelicum library consists of that part of the textual patrimony of the Angelicum not expropriated by the Italian government with the Biblioteca Casanatense in 1870. At the convent of Saints Sixtus and Dominic the library originally housed 40,000 volumes in the Sala delle Colonne. As the library grew space was found under the Aula Magna for a library whose large windows face out to the palm trees of the Angelicum walled garden.[204] The collection that remains at the college today consists of approximately 400 000 volumes, about 6 000 manuscripts, 2 200 incunabula including 64 Greek codices, and 230 Hebrew texts including 5 Samaritan codices is open to the scholarly community.

Among the library's treasures is included the original copy of the doctoral thesis Doctrina de fide apud S. Ioannem a Cruce (The Doctrine of Faith in St. John of the Cross) written by the future Pope John Paul II, Karol Józef Wojtyła, under the direction of Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange and defended on 19 June 1948[205]

The Angelicum garden

On the south side of campus the walled garden is bordered by private properties. At the garden entrance stands a fountain by Giovanni Battista Soria built circa 1630.[198] The garden is planted with trees of many kinds: orange, lemon, pistachio, olive, fig, palm and laurel, as well as with grape vines, and is an oasis of calm and silence, a figure of paradise in the midst of the bustling eternal city. In 1946 in this garden the young student Karol Wojtyla, future Pope John Paul II, would stroll and visit daily what he called the "miraculous tree", an ancient olive from which springs incredibly the branches of a palm, a fig, and a laurel.[206]

The University Church, Chapel, and Choir

Along the north side of campus are found the university's Church of Saints Dominic and Sixtus, the Blessed Sacrament Chapel, and the Choir. The church has been the subject of numerous works of art. In the 18th century Antonio Canaletto made a pen and ink study with grey wash and black chalk, today in the collection of the British Museum, described as depicting "the Church of SS Domenico e Sisto, Rome; with a sweeping double staircase to the entrance, in the foreground a man bowing to two approaching ladies".[207] Italian born American painter John Singer Sargent during his extensive travels in Italy made an oil painting of the exterior staircase and balustrade of the campus's Church of Saints Dominic and Sixtus in 1906.[208] Sargent described the ensemble as "a magnificent curved staircase and balustrade, leading to a grand façade that would reduce a millionaire to a worm".[209] The painting now hangs at the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University. Sargent used the architectural features from this painting later in a portrait of Charles William Eliot, President of Harvard University from 1869 to 1909.[210] Sargent made several preliminary pencil sketches of the balustrade and staircase, which are in the collection of the Harvard University art collection of the Fogg Museum.[211] The Church as also been depicted by Ettore Roesler Franz and Eero Saarinen.[212] The Church and stair also feature in the 1950 film Prima comunione by director Alessandro Blasetti,[213] which is on the list of the 100 Italian films to save.[214][215][better source needed][216][217][218]

Surrounding area

The northern flank of campus borders via Panisperna across from the perimeter wall of the Roman Villa Aldobrandini, a 17th-century princely villa whose gardens were truncated by the construction of Via Nazionale in the 19th century, and which today houses the headquarters of the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT). Behind the campus intersecting with Via Nazionale is the "Via Mazzarino", named after Michele Mazzarino professor of theology at the college after 1628 who[219] was appointed Master of the Sacred Palace under Pope Urban VIII in 1642, and Archbishop of Aix-en-Provence in 1645 by Pope Innocent X. Mazzarino's brother Giulio Mazzarino, known as "Jules Mazarin" was chief minister under Louis XIV of France.[220] The East edge of campus is bound by Salita del Grillo beyond which is the Markets and Forum of Trajan.

Remove ads

General information

Summarize

Perspective

Angelicum traditions and annual events

- Inauguration of the Academic Year takes place in October with a solemn "Mass of the Holy Spirit" and the conferral of academic degrees (see "Angelicum regalia" below).

- Inaugural Lecture. In early November a "prolusione" or formal address is given by an invited speaker to mark the inauguration of the academic year:

- 2009 Wojciech Giertych, Theologian of the Pontifical Household, "Why There Are So Few Thomist Saints?"[221]

- 2008 Francesco Coccopalmerio, President of the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts, "La natura dell'attività' del Legislatore nella Chiesa"[222]

- 1953 Alcide De Gasperi, Founder Christian Democratic Party, Italian Prime Minister 1945–1953, European Union founding member.[223] "The International Workers Movement and a United Europe".[224]

- 1948 Giulio Andreotti, member of provisional parliament tasked with writing the new Italian constitution, and future Prime Minister of Italy (1972–73; 1976–79; 1989–92), "The Intellectual Mission of Italy and of a United Europe".[225]

- 1928 Réginald Marie Garrigou-Lagrange, theologian.[226]

- Encomium of St. Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum patron: Traditionally on 7 March, the pre Vatican II feast day and death anniversary of St. Thomas Aquinas a high Solemn Mass is offered, followed by an encomium honoring the "angelic doctor." This is one of the Angelicum's oldest traditions dating back to 6 February 1344 when Pope Clement VI granted to those visiting a church of the Dominican Order on 7 March the feast of St. Thomas Aquinas the remission of one year and forty days of purgatory.[227] After the offertory of the Mass the motet O Doctor optime by Vincenzo De Grandis (1577–1646)[228] was sung in four voices. After Mass a Dominican student or invited speaker recites an encomium in honor of St. Thomas.[229]

- 2013, Angelo Vincenzo Zani presider, Congregation for Catholic Education Secretary, Titular Archbishop of Volturnum, Angelicum Theology Faculty alumnus.

- 2012, Giuseppe Sciacca presider, Secretary-General of the Governatorate of Vatican City, alumnus of the Angelicum Canon Law Faculty.

- 1932, Martin Stanislas Gillet, Master of the Order of Preachers (1929–1946)[230]

- 1914, Hyacinthe-Marie Cormier Master of the Order of Preachers.

- 1903, Domenico Toncelli. Il genio della Scienza. Panegirico di S. Tommaso d'Aquino.[231]

- 1893, Cardinal Sebastiano Galeati[232][better source needed] Archbishop of Ravenna gave the encomium.[233]

- 1882, Francesco Satolli[234]

- 1880, Girolamo Pio Saccheri.[235]

- 1874, Jesuit priest and scholar Giovanni Maria Cornoldi gave the encomium.[236]

- 1661, Angelo Paciucchelli[237]

- 1650, Antonio Francesco Fracassi[238]

- 1635 c., Raimondo Capizucchi[239]

- 1634, Joseph Maria Avila, "Laudatio Divi Thomae Aquinatis"[240]

- 1633, Latino Pagano Orsini[241]

- 1622, Reginaldo Lucarini,[242] Master of the Sacred Palace (1643),[243] gave the encomium[244]

- 1615, Ignazio Cianti[245]

- 1571, Cornelio Firmano, Bishop of Osimo (1574-1588)[246]

- 1562, Juan Gallo, representative of Philip II at the Council of Trent[247] gave the encomium.[248]

- 1555, Pope Paul IV gave the encomium in praise of St. Thomas to the community at the Minerva.[249]

- 1510, Antonio Pucci.[250]

- 1496, Martin de Viana.[251]

- 1495, Tommaso Inghirami, poet and orator, delivered his "Panegyricus in memoriam divi Thomae Aquinatis"[252]

- 1491, Bernardo Basin (c. 1445–1510), author of the Tractatus exquisitissimus de magicis artibus ac magorum malificiis (1483) gave the encomium at the Minerva.[253]

- 1487, Martin de Nimira, Croatian Latinist[254]

- 1485, Francesco Matarazzo, Renaissance chronicler, gave the encomium.[255]

- 1483 c., Aurelio Lippo Brandolini

- 1469, Giovanni Antonio Campani

- 1457, Lorenzo Valla famed humanist. The Dominicans of the Minerva studium generale pressed Valla to voice criticism of scholastic thomism.[41]

- 1450, Rodrigo Sánchez de Arévalo.[256]

- Concert Talent Show is offered annually by students and professors consisting of a multicultural exhibition of music, song and dance from around the world.

- The Albertus Magnus lectio magistralis in honor of St. Albert the Great, teacher of St. Thomas Aquinas and Doctor of the Church is given on or near 15 November, feast day of St. Albert.

Other recent lectures and events of note related to the university's mission include:

- 2018, 7 March, Rocco Buttiglione gave a lectio entitled "De singularibus non est scientia: St. Thomas and a recent controversy in moral theology".[257]

- 2014, 7 May, Symposium in honor of Dominican Friar Giuseppe Girotti, martyr at Dachau concentration camp in 1945, beatified at Alba, Piedmont on 26 April 2014.[177]

- 2013, 16 April, Romano Prodi, former President of the European Commission and former Prime Minister of Italy gave a lectio magistralis at the Angelicum entitled "I grandi cambiamenti della politica e dell'economia mondiale: c'è un posto per l'Europa?" ("The Great Changes in Politics and the World Economy: Is there Room for Europe?). Prodi was sponsored by the Angelicum and the Università degli Studi Guglielmo Marconi[258][better source needed] as promotion for the degree offered in Political Science, "Scienze Politiche e del Buon Governo."[177] A few days after his lecture Prodi was selected by PD parliamentarians to be their candidate for President of Italy during the 2013 presidential election.

- 2008, 12 December, Cherie Blair gave a lecture "Religion as a Force in protecting Women's Human Rights"[259][260][261] The lecture was alternatively entitled "The Church and Women's Rights: time for a fresh perspective?"[262]

The Angelicum Alumni Achievement Award is conferred upon alumni who have distinguished themselves by serving the Church's mission in exceptional ways. The award is bestowed on 7 March, the old feast day of Saint Thomas Aquinas, patron of the university. Past recipients include Cardinal John Foley (2009), Archbishop Peter Smith (2011), and Cardinal Edwin Frederick O'Brien (2012).

The Pope John Paul II Lecture on Interreligious Understanding is delivered towards the end of each academic year and features a world religious leader or renowned expert who embodies the ideals of inter-religious understanding. The lecture is a major event at the Angelicum and attracts the Roman academic community as well as the international diplomatic community. To date the Annual Lecture has hosted an array of prominent and Internationally known academics and religious leaders as key note speakers."[178]

- 2012 Cardinal Kurt Koch, President, Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity and Pontifical Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews, "Building on Nostra Aetate: 50 Years of Christian- Jewish Dialogue"

- 2011 Professor David F. Ford, Anglican theologian, Cambridge University Regius Professor of Divinity, Cambridge Inter-Faith Programme Director, "Jews, Christians and Muslims Meet around their Scriptures: An Inter-faith Practice for the Twenty-first Century"

- 2010 Mona Siddiqui, Islamic Scholar and Professor of Islamic Studies and Public Understanding at the University of Glasgow, "Islamic Perspectives on Judaism and Christianity"

- 2009 Rabbi Michael Schudrich, Chief Rabbi of Poland, "A Rabbi's Reflection on the Teachings of John Paul II"

- 2008 Donald Wuerl, S.T.D. Archbishop of Washington, DC, "Unifying Religious Threads that Provide a Common Ground for Peace"

- A Eucharistic Procession led by a notable Church dignitary takes place at the end of each academic year. Typically the procession departs at 1:00 p.m. from the Blessed Sacrament Chapel, continues around the Angelicum's central courtyard, through the main corridors and ends in the Church of Saints Dominic and Sixtus for Exposition and Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament.

- In 2013 Miroslav Konštanc Adam, Angelicum Rector, led the procession on 15 May.[177]

- In 2012 James D. Conley, Apostolic Administrator of the Archdiocese of Denver, USA, led the procession on 3 May.

- In 2011 Cardinal Marc Ouellet, Prefect for the Congregation for Bishops, led the procession on 27 May.

- In 2010 it was led by Piero Marini.

- In 2009 Raymond Leo Burke, Prefect for the Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura, led the procession.

- Eucharistic Exposition and Adoration is offered by no Pontifical University in Rome other than the Angelicum. On class days (Monday-Friday) from 8:00am–6:20pm Eucharistic Adoration takes place in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel near the entrance of the Choir at the Angelicum. Students can sign up to be "Eucharistic Guardians" for an hour giving them the opportunity to pray for a series of intentions administration, faculty, staff and students post in the intention sheet. This is organized by the university chaplaincy and the students themselves following the Dominican tradition of the Eucharist being at the center of the life of study.[263]

- Formal Closure of the Academic Year is celebrated with a Solemn Mass at the end of May.

School motto and hymn

In 1908, when the college was transformed it into the Collegium Pontificium Internationale Angelicum, Blessed Hyacinthe-Marie Cormier bestowed upon it his personal motto as Master General of the Order of Preachers, caritas veritatis. This Latin phrase literally translated as the charity of truth appears in The City of God[264] by St. Augustine of Hippo, and is quoted by St. Thomas Aquinas in comparing the active and the contemplative life: "Unde Augustinus dicit XIX De civ. Dei, Otium sanctum quaerit caritas veritatis; negotium justum, scilicet vitae activae, suscipit necessitas caritatis,"[265] which Aldous Huxley translates in The Perennial Philosophy as: "The love of Truth seeks holy leisure; the necessity of love undertakes righteous action."[266] Augustine's phrase also appears in the writings of William of St-Thierry[267]

The Angelicum does not currently have a school song.[268]

Angelicum regalia

Academic dress for Angelicum graduates consists of a black toga or academic gown with trim to follow the color of the faculty, and an academic ring. In addition, for the Doctorate degree a four corned biretta is to be worn, and for the Licentiate degree a three corned biretta is to be worn.[269] Traditionally the ceremony at which the biretum is imposed is called the "birretatio".[270]

For those holding doctoral degrees from a pontifical university or faculty "the principal mark of a Doctor's dignity is the four horned biretta."[271] The 1917 Code of Canon Law canon 1378 and 1922 commentary prescribe the four corned biretum doctorale and doctoral ring or annulum doctorale for doctorates in philosophy, theology, canon law, specifying that the biretum should decorated according to the color of the faculty ("diverso colore ornatum pro Facultate").[272] The 'traditional' Angelicum biretta is white to correspond to the white Dominican habit.[273] However, the Academic Senate of the Angelicum in its May 2011 meeting indicated that for the Licentiate and Doctorate a black biretta may be used with colored piping and pom to follow the color of the faculty.[274]

The biretta is lay in origin and was adopted by the Church in the 14th century: "Many synods ordered the use of this cap [the pileus or skull cap] as a substitute for the hood, and in one instance the synod of Bergamo, 1311, ordered the clergy to wear the bireta on their heads after the manner of laymen'." Herbert Norris, Church Vestments: Their Origin and Development, 1950, 161).

Angelicum athletics

The Olympic motto Citius, Altius, Fortius (Faster, Higher, Stronger) was coined by Henri Didon for a Paris youth gathering in 1891, and later proposed as the official Olympic motto by his friend Pierre de Coubertin in 1894 and made official in 1924. Didon completed his theological studies at the College of Saint Thomas in 1862.[275][276]

The Clericus Cup is a soccer tournament that takes place annually between the various pontifical universities of Rome. The teams are composed of seminarians, priests, and lay students studying in each of the pontifical universities. The league was started by Cardinal Secretary of State, Tarcisio Bertone who is an unapologetic football fan. The Angelicum first participated in 2011, and came in second place in 2012. During the history of the Clericus Cup, players have come from 65 countries, with the majority coming from Brazil, Italy, Mexico, and the United States. The annual tournament is organized by the Centro Sportivo Italiano. Officially, the goal of the league is to "reinvigorate the tradition of sport in the Christian community." In other words, to provide a venue for friendly athletic competition among the thousands of seminarians and lay students, representing nearly a hundred countries, who study in Rome.[277]

In November 2011 Minerva the Owl was voted in as the Angelicum mascot.[2]

Student housing

The Angelicum does not provide housing primarily intended for lay students. However, assistance finding local student housing is offered by the Angelicum Office of Student Affairs (ASPUST).[278] The office is located in the Palazzo dei Decanati or Deans' Building at the West end of campus, just inside the gates to the right.

The Lay Centre at Foyer Unitas is an international college for lay students within walking distance of the Angelicum.

The Convitto San Tommaso was established by the Dominican Order in 1963 as a place of residence in Rome for secular priests who come to the Rome in order to pursue higher studies at one or other of the Roman Universities. There are approximately 55 student priests. They come from five continents of the world. Three Dominicans live in the house to serve the practical and spiritual needs of the house: the Rector, the Spiritual Director, and the Bursar. The life of the house focuses on daily celebration of the Eucharist.[279]

Student activities

The following is a sample of student activities:

- The Associazione Studentesca Pontificia Università San Tommaso (ASPUST), or Student Association of the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas, is housed in the Angelicum Office of Student Affairs.[280]

ASPUST holds elections for its offers in mid November each year.

ASPUST offers services to students and prospective students of the Angelicum such as information about health services and insurance, information about apartment hunting, other services relating to public transportation, computers, cafeterias, and a blog that reports on student activities.

- At various times during the academic year one of the Faculties or the Student Association sponsors a day-long pilgrimage for students and faculty to locales such as Assisi, Norcia, Cascia, Subiaco, Orvieto, Siena, or Roccasecca, birthplace of St. Thomas Aquinas.

- Chaplaincy of the Angelicum sponsors a "Karol Wojtyla Discussion Group" that meets weekly.

- The Angelicum Choir meets for practice each week in the chapel.[281]

Bookstore

The Angelicum Bookshop is run by Libreria Leoniana of Rome. Located on near the University Library, it specializes in ecclesiastical literature, Italian and foreign language literature, and provides stationery, photo-reproduction, computer, and bindery services. Hours during the academic year are 9:00am to 1:00pm and 3:00pm to 6:00pm. It is closed Saturdays and the month of August.[282]

Remove ads

Publications and media