Loading AI tools

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Paenitentiale Ecgberhti (also known as the Paenitentiale Pseudo-Ecgberhti, or more commonly as either Ecgberht's penitential or the Ecgberhtine penitential) is an early medieval penitential handbook composed around 740, possibly by Archbishop Ecgberht of York.

| Paenitentiale Ecgberhti | |

|---|---|

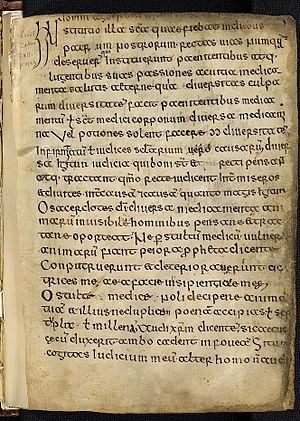

Folio 5r from the Vatican manuscript, Pal. lat. 554, showing the beginning of the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti, with the title partly worn away | |

| Also known as | Paenitentiale Pseudo-Ecgberhti |

| Audience | Catholic clergy |

| Language | medieval Latin |

| Date | ca. 740? |

| Authenticity | questionable |

| Manuscript(s) | eleven, plus fragments |

| Genre | penitential, canon law collection |

| Subject | ecclesiastical and lay discipline; ecclesiastical and lay penance |

This work should not be confused with the vernacular works known as the Old English Penitential (formerly the Paenitentiale Pseudo-Ecgberhti) and the Scriftboc (formerly the Confessionale Pseudo-Ecgberhti).

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (March 2014) |

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (March 2014) |

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (March 2014) |

There are eleven extant manuscripts that contain the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti, dating from as early as the end of the eighth century to as late as the thirteenth, ranging geographically from southern Germany to Brittany to England. The sigla given below (V6, O1, etc.) are based on those established by the Körntgen–Kottje Editionsprojekt for the Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina, vol. 156, a project whose goal is to produce scholarly editions for all major early medieval penitentials; sigla in parentheses are those used by Reinhard Haggenmüller in his 1991 study.

| Siglum | Manuscript | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| Cb2 (C2) | Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 265, pp. 3–208 (written middle of eleventh century, possibly in Worcester) | Paenitentiale Ecgberhti as part of the C recension of Wulfstan of York's Collectio canonum Wigorniensis |

| Le1 | Leiden, Bibliotheek der Rijksuniversiteit, Cod. Vul. 108 nr. 12 [1] (written ninth or tenth century in northeastern Francia)[2] | Paenitentiale Ecgberhti (fragmentary: prologue + cc. 4.8–5.1);[3] fragments of an unidentified penitential (including the Edictio Bonifatii);[4] Canones Basilienses (fragmentary: cc. 1–4a)[5] |

| Li1 | Linz, Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek, Cod. 745 (written middle of ninth century, probably in southern Germany)[6] | Paenitentiale Ecgberhti (fragment: cc. 11.10 and 12.5–7) |

| M17 | Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 22288, fols 1–81 (written first half of twelfth century, possibly in Bamberg) | Excarpsus Cummeani; Paenitentiale Ecgberhti; unidentified canon law collection in three books (including: Paenitentiale Theodori [U version; excerpts]; Paenitentiale Cummeani [excerpts]); Liber proemium veteris ac novi testamenti; De ortu et obitu patrum; Micrologus de ecclesiasticis observationibus; Admonitio synodalis |

| O1 | Oxford, Bodleian Library, Barlow 37 (6464) (written end of twelfth or beginning of thirteenth century, possibly in Worcester) | Paenitentiale Ecgberhti (with Ghaerbald's Capitula episcoporum I appended), as part of the D recension of Wulfstan's Collectio canonum Wigorniensis |

| O5 | Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 718 (2632) (written second half of tenth century, probably in either Sherborne, Canterbury or Exeter) | Paenitentiale Ecgberhti with Ghaerbald's Capitula episcoporum I appended; confessional ordines; Books 2–4 of the Collectio canonum quadripartita |

| P22 | Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 3182 (written second half of tenth century in Brittany) | A collection of chapters (mostly canonical and penitential) entitled "Incipiunt uerba pauca tam de episcopo quam de presbitero aut de omnibus ecclesię gradibus et de regibus et de mundo et terra", more commonly known as the Collectio canonum Fiscani or the Fécamp collection. The contents are as follows: Liber ex lege Moysi;[7] notes on chronology;[8] a brief note on Bishop Narcissus of Jerusalem (Narcisus Hierosolimorum episcopus qui fecit oleum de aqua ... orbaretur et euenit illis ut iurauerunt); Incipiunt remissiones peccatorum quas sanctus in collatione sua Penuffius per sanctas construxit scripturas (= large excerpt from Cassian's Collationes c. 20.8); more notes on chronology;[9] Pastor Hermae cc. 4.1.4–4.4.2 (versio Palatina); scriptural excerpts on chastity, marriage and the oaths of one's wife; Incipiunt uirtutes quas Dominus omni die fecit (chapters on Sunday, the days of Creation, and the Last Judgment); Collectio canonum Hibernensis cc 1.22.b–c (on the murder of priests, and bishops' duty to persist in their own dioceses); Collectio canonum Hibernensis (A version, complete copy); Excerpta de libris Romanorum et Francorum (a.k.a. Canones Wallici); Canones Adomnani (cc. 1–7 only), with an extra chapter appended (Equus aut pecus si percusserit ... in agro suo non reditur pro eo); Capitula Dacheriana; Canones Adomnani (complete copy); Incipiunt canones Anircani concilii episcoporum XXIIII de libro III (a small collection of canones from the council of Ancyra in modified versio Dionysiana II form);[10] Incipiunt iudicia conpendia de libro III (a small collection of canons including a canon from the council of Neocaesarea (in modified versio Dionysiana II form) and excerpts from the Paenitentiale Vinniani);[11] Canones Hibernenses II (on commutations), with Synodus Luci Victorie cc. 7–9 appended; Isidore, Etymologiae (excerpts on consanguinity); commentary on the Book of Numbers (on oaths); Isidore, Etymologiae (excerpts on consanguinity and heirs); Institutio ęclesiasticae auctoritatis, qua hi qui proueniendi sunt ad sacerdotium, profiteri debent se obseruaturos, et si ab his postea deuiauerint canonica auctoritate plectentur (excerpts on ordination);[12] Collectio canonum Dionysio-Hadriana (ending with canons of the council of Rome in 721); Quattuor synodus principales; Isidore, Etymologiae (excerpts on the ancient councils); Hii sunt subterscripti heretici contra quos factae sunt istę synodi: Arrius ... Purus, Stephanus; De ieiunio IIII temporum anni (In mense Martio ... nulli presbiterorum liceat uirginem consecrare); Libellus responsionum; Pope Gregory I, Epistula 9.219 (excerpt); Pope Gregory I, Epistula 9.214 (excerpt);[13] De decimis et primogenitis et primitiuis in lege (excerpts on tithes);[14] Canones Hibernenses III (on tithes); Paenitentiale Gildae; Synodus Aquilonis Britanniae; Synodus Luci Victoriae; Ex libro Davidis; Capitula Dacheriana (c. 21 [first part] only); Canones Adomnani (cc. 19–20 only); Capitula Dacheriana (cc. 21 [second part, with si mortui inueniantur uel in rebus strangulati appended] and 168 only); excerpts from St Paul (on food); excerpts on hours and the order of prayer;[15] De pęnitentia infirmorum (Paenitentiale Umbrense c. I.7.5 [in modified form] + Paenitentiale Columbani A c. 1 [first part]); De recitentibus aliorum peccata (Paenitentiale Cummeani c. [8]9.19); De oratione facienda etiam pro peccatoribus (Scriptura dicit in commoratione mortuorum: etiam si peccavit, tamen patrem ... dum angeli Dei faciunt); Paenitentiale Bigotianum; Theodulf, Capitulare I ("Kurzfassung");[16] Isidore, De ecclesiasticis officiis (excerpt: De officiis ad fidem venientium primo de symbolo apostolico quo inbuuntur competentes, with commentary on Deuteronomy 22–3 appended); Canones Hibernenses IV; excerpts on marriage (mainly from Augustine and Jerome, but also including Synodus II Patricii c. 28); excerpts on kings;[17] excerpts on sons and their debts;[18] Collectio canonum Hibernensis c. 38.17; Patricius dicit (= Canones Hibernenses IV c. 9), Item synodus Hibernensis (= Canones Hibernenses IV c. 1–8);[19] De iectione ęclesie graduum ab ospicio (= Canones Hibernenses V); chapters from Exodus and Deuteronomy (excerpts on virgins and adulterers); on the ordo missae (excerpt from Isidore's De ecclesiasticis officiis); Liber pontificalis (Linus natione italus ... Bonifacius LXVIII natione romanus hic qui obtinuit ... se omnium eclesiarum scribebat); De duodecim sacrificiis (excerpt from Pseudo-Jerome's Disputatio de sollempnitatibus paschae);[20] the ten commandments (Decim precepta legis in prima tabula ... rem proximi tui mundi cupiditatem); excerpts on hours and song (including Pro quibus uirtutibus cantatur omnis cursus, De pullorum cantu, De matudinis, etc.); a brief tract explaining the reason for the flood;[21] De eo quod non nocet ministerium ministrantis sacerdotis contagium uitę (= Collectio canonum Hibernensis [B version] c. 2.12);[22] Canones Hibernenses VI; Capitulare legibus addenda a. 803; Lex Salica emendata; two forged letters purporting to represent a discussion between Pope Gregory I and Bishop Felix of Messina (on consanguinity, the Anglo-Saxons, and the nature of the Pope's Libellus responsionum);[23] Theodulf, Capitulare I (fragmentary);[24] Paenitentiale Ecgberhti (fragmentary: beginning partway through c. 2); Pseudo-Jerome, De duodecim triduanis |

| Se2 | Sélestat, Bibliothèque humaniste, MS 132 (written middle of ninth century, possibly in Mainz) | rites for exorcism; incantations; Paenitentiale Ecgberhti; Paenitentiale Bedae; Excarpsus Cummeani |

| Sg10 | St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Codex 677 (written middle of tenth century, possibly in St. Gallen) | episcopal capitularies of Theodulf and Haito of Mainz; prayers for penitents; Paenitentiale Ecgberhti; excerpts from Isidore, Ambrose, etc.; canons of the council of Nicaea (325); Alcuin's De virtutibus et vitiis; Letter of Charlemagne to Alcuin; Caesarius's Sermo de paenitentia; Charlemagne's Admonitio generalis |

| V4 | Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 294, fols 78–136 (written ca 1000 in Lorsch) | Paenitentiale Ecgberhti (incomplete: c. V.2–end); Sonderrezension der Vorstufe des Paenitentiale additivum Pseudo-Bedae–Ecgberhti; canonical and creedal statements |

| V5 | Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 485 (written second half of ninth century in Lorsch) | lections, prayers, a Gregorian sacramentary, canonical excerpts, a calendar, a necrology, and tracts on miscellaneous subjects, including weights and measures, confession, and astronomy; Paenitentiale Ecgberhti; excerpts from the Excarpsus Cummeani; episcopal capitularies of Theodulf, Ghaerbald and Waltcaud; Sonderrezension der Vorstufe des Paenitentiale additivum Pseudo-Bedae–Ecgberhti; Paenitentiale Cummeani; Paenitentiale Theodori (U version) |

| V6 | Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 554, fols 5–13 (written ca 800 in Germany, or possibly England) | Paenitentiale Ecgberhti; excerpts from the Excarpsus Cummeani (added by later hand); Admonitio Pseudo-Bedae (added by later hand) |

| W9 | Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex lat. 2223 (written beginning of ninth century in the Main river region) | Paenitentiale Theodori (U version); Paenitentiale Bedae; Paenitentiale Cummeani (excerpt); Capitula iudiciorum (previously known as the Poenitentiale XXXV capitulorum); Libellus responsionum; miscellaneous creedal and theological works; Paenitentiale Ecgberhti |

Haggenmüller divided these eleven surviving witnesses of the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti into three groups, based broadly on the regions in which they were produced, the nature and arrangement of their accompanying texts, and shared readings in the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti itself.[25] The 'Norman' group consists of some of the youngest manuscripts (P22, O5, C2, O1), most of which originated in regions under Norman influence or control, namely tenth-century Brittany and eleventh to twelfth-century England; only O5 originates in a non-Norman context. The 'South-German' group (Se1, Sg10, V4, M17) represents a textual tradition emanating from a region in southern Germany (perhaps the Lake Constance area), even though only one constituent witness (Sg10) originates in a South-German centre. Haggenmüller's third group, the 'Lorsch' group, includes three manuscripts (V6, W9, V5), two of which (V6, W9) are the oldest extant witnesses to the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti tradition. Of the three manuscripts in this group, however, only one (V5) is known with certainty to have been produced at Lorsch (though V6 had provenance there by the first half of the ninth century). It is currently unknown where the two earliest witnesses of the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti (V6, W9) originate from, though it was likely not in the same place since they present rather different versions of the text.

In addition to the eleven main witnesses listed above, the prologue to the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti is also transmitted in the following manuscripts:

The Paenitentiale Ecgberhti is also transmitted in somewhat altered form as part of two later penitential texts known as the Vorstufe des Paenitentiale additivum Pseudo-Bedae–Ecgberhti (or Preliminary Stage of the Unified Bedan-Ecgberhtine Penitential, in which the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti is affixed to the end of the Paenitentiale Bedae) and the Paenitentiale additivum Pseudo-Bedae–Ecgberhti (or Unified Bedan-Ecgberhtine Penitential; like the Preliminary Stage, but the whole is now preceded by the prefaces of both the Paenitentiale Bedae and the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti), and in greatly altered form in the still later Paenitentiale mixtum Pseudo-Bedae–Ecgberhti (or Merged Bedan-Ecgberhtine Penitential, in which the chapters of both the Paenitentiale Bedae and the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti are mixed together and arranged by topic).

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (March 2014) |

The Paenitentiale Ecgberhti itself has been edited twice and reprinted once:

Much more numerous are editions of the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti in the later modified forms mentioned above, namely the Vorstufe des Paenitentiale additivum Pseudo-Bedae–Ecgberhti, the Paenitentiale additivum Pseudo-Bedae–Ecgberhti, and the Paenitentiale mixtum Pseudo-Bedae–Ecgberhti. These works, which present the Paenitentiale Ecgberhti material in sometimes greatly modified form, have been edited and reprinted many times since the early modern period.

The Vorstufe des Paenitentiale additivum Pseudo-Bedae–Ecgberhti has been edited four times:

The Paenitentiale additivum Pseudo-Bedae–Ecgberhti has been edited three times and reprinted nine times:

The Paenitentiale mixtum Pseudo-Bedae–Ecgberhti has been edited twice and reprinted twice:

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.