Noel Annan, Baron Annan

British intelligence officer and historian (1916–2000) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Noel Gilroy Annan, Baron Annan OBE (25 December 1916 – 21 February 2000) was a British military intelligence officer, author, and academic. During his military career, he rose to the rank of colonel and was appointed to the Order of the British Empire as an Officer (OBE). He was provost of King's College, Cambridge, 1956–66, provost of University College London, 1966–78, vice-chancellor of the University of London, and a member of the House of Lords.

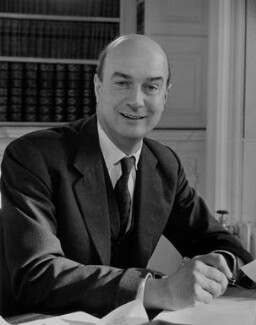

The Lord Annan | |

|---|---|

Annan in January 1957. | |

| Born | 25 December 1916 |

| Died | 21 February 2000 (aged 83) |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | King's College, Cambridge |

| Occupation(s) | British military intelligence officer, author, and academic |

Annan's publications include Leslie Stephen (1951)—awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, Roxburgh of Stowe (1965), Our Age (1990), described by Professor John Gray in the New Statesman as a "marvellous compendium of the higher gossip", Changing Enemies (1995), and The Dons (1999). His best-known essay is "The Intellectual Aristocracy", which illustrates, according to Robert Fulford in the National Post, the "web of kinship that united British intellectuals (the Darwins, Huxleys, Macaulays, etc.) in the 19th and early 20th centuries."[1]

Early life and education

Annan was born in Gloucester Terrace, London, and was educated at St. Winnifred's School, Seaford in East Sussex, and Stowe School.[2] At Stowe, he was head of Temple House, and editor of the school newspaper The Stoic. He went up to King's College, Cambridge,[2] in 1935, where he read history, then continued for a fourth year to read law. While at King's, he was recruited into the Cambridge Apostles, a secret debating society whose members included Guy Burgess and Michael Straight, who later became spies for the Soviet Union (see Cambridge Five).[3]

Military career

In October 1940, he entered officer cadet training, and in January 1941 was commissioned in the Intelligence Corps and posted to MI14, a department of the War Office, where "Annan was given an important job in operational intelligence studying the movement by rail of German forces".[2] In 1942, he was posted to the Joint Intelligence Staff in the War Cabinet Office, which was located with Winston Churchill in his bunker. In 1944, he was transferred to Paris to become the French liaison officer with British military intelligence, later becoming a senior officer in the political division of the British Control Commission in Germany. Annan was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1946.[4]

Academic career

Annan returned to King's in 1946, where he had been elected to a fellowship in absentia in 1944 at the unusually young age of 28.[2] He joined the economics faculty and lectured in politics.

In June 1950, he married the author and critic Gabriele Ullstein, and they had two daughters – Lucy (born 1952) and Juliet (born 1955).

He was elected Provost of King's in 1956. In 1966, he took up the post of Provost of University College London, then from 1978 until 1981, was Vice-Chancellor of the University of London – the first person to take on the role full-time.[2] He was created a life peer on 16 July 1965 as Baron Annan, of the Royal Burgh of Annan in the County of Dumfries.[5]

He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1974.[6] Essex University awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1967.[citation needed] He was also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society.[citation needed]

Committees

He acted as a trustee of the British Museum 1963–1980, and of the National Gallery 1978–85. He also chaired the Royal Commission on Broadcasting, which concluded in 1977 (see Annan Committee). He was the first chairman of the Trustee's education committee at Churchill College, Cambridge.

Bibliography

Summarize

Perspective

- Leslie Stephen: His Thought and Character in Relation to His Time. London: MacGibbon & Kee. 1951.

- The Curious Strength of Positivism in English Political Thought. London: Oxford University Press. 1959.

- Roxburgh of Stowe: The Life of J. F. Roxburgh and His Influence in the Public Schools. London: Longmans. 1965.

- The Disintegration of an Old Culture. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1966.

- How Dr. Adenauer Rose Resilient from the Ruins of Germany. London: Institute of Germanic Studies, University of London. 1983. ISBN 0-85457-116-7.

- Leslie Stephen: The Godless Victorian (rev. ed.). London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. 1984. ISBN 0-297-78369-6.

- Our Age: Portrait of a Generation. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. 1990. ISBN 0-297-81129-0.

- Changing Enemies: The Defeat and Regeneration of Germany. London: HarperCollins. 1995. ISBN 0-00-255629-4.

- The Dons: Mentors, Eccentrics and Geniuses. HarperCollins. 1999. ISBN 0-00-257074-2.

Annan was a signatory to a famous letter published in The Times in 1958 which precipitated the establishment of the Homosexual Law Reform Society, which campaigned for homosexual law reform. (See Patrick Higgins, Heterosexual Dictatorship: Male Homosexuality in Post-War Britain, London: Fourth Estate Ltd; 1996, p. 125.)

See also

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.