Loading AI tools

Japanese university professor, scholar, and Kyoto School philosopher From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

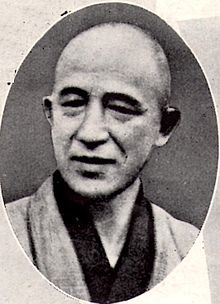

Keiji Nishitani (西谷 啓治, Nishitani Keiji, February 27, 1900 – November 24, 1990) was a Japanese philosopher. He was a scholar of the Kyoto School and a disciple of Kitarō Nishida. In 1924, Nishitani received his doctorate from Kyoto Imperial University for his dissertation "Das Ideale und das Reale bei Schelling und Bergson". He studied under Martin Heidegger in Freiburg from 1937 to 1939.

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (April 2015) |

Keiji Nishitani | |

|---|---|

| 西谷 啓治 | |

| |

| Born | February 27, 1900 |

| Died | November 24, 1990 (aged 90) |

| Nationality | |

| Alma mater | Kyoto Imperial University |

| Notable work | Religion and Nothingness |

| Era | Contemporary philosophy |

| Region | |

| School | Kyoto School |

| Institutions | Kyoto Imperial University |

Main interests | Philosophy of religion, nihilism, nothingness, emptiness, mysticism |

Nishitani held the principal Chair of Philosophy and Religion at Kyoto University from 1943 until becoming emeritus in 1964. He then taught philosophy and religion at Ōtani University. At various times Nishitani was a visiting professor in the United States and Europe.

According to James Heisig, after being banned from holding any public position by the United States Occupation authorities in July 1946, Nishitani refrained from drawing "practical social conscience into philosophical and religious ideas, preferring to think about the insight of the individual rather than the reform of the social order."[1]

In James Heisig's Philosophers of Nothingness Nishitani is quoted as saying "The fundamental problem of my life … has always been, to put it simply, the overcoming of nihilism through nihilism."[2]

On Heisig's reading, Nishitani's philosophy had a distinctive religious and subjective bent, drawing Nishitani close to existentialists and mystics, most notably Søren Kierkegaard and Meister Eckhart, rather than to the scholars and theologians who aimed at systematic elaborations of thought. Heisig further argues that Nishitani, "the stylistic superior of Nishida," brought Zen poetry, religion, literature, and philosophy organically together in his work to help lay the difficult foundations for a breaking free of the Japanese language, in a similar way to Blaise Pascal or Friedrich Nietzsche.[1] Heisig argues that, unlike Nishida who had supposedly focused on building a philosophical system and who towards the end of his career began to focus on political philosophy, Nishitani focused on delineating a standpoint "from which he could enlighten a broader range of topics," and wrote more on Buddhist themes towards the end of his career.[1]

In works such as Religion and Nothingness, Nishitani focuses on the Buddhist term Śūnyatā (emptiness/nothingness) and its relation to Western nihilism.[3] To contrast with the Western idea of nihility as the absence of meaning Nishitani's Śūnyatā relates to the acceptance of anatta, one of the three Right Understandings in the Noble Eightfold Path and the rejection of the ego in order to recognize the Pratītyasamutpāda, to be one with everything. Stating: "All things that are in the world are linked together, one way or the other. Not a single thing comes into being without some relationship to every other thing."[4] However, Nishitani always wrote and understood himself as a philosopher akin in spirit to Nishida insofar as the teacher—always bent upon fundamental problems of ordinary life—sought to revive a path of life walked already by ancient predecessors, most notably in the Zen tradition. Nor can Heisig's reading of Nishitani as "existentialist" convince in the face of Nishitani's critique of existentialism—a critique that walked, in its essential orientation, in the footsteps of Nishida's "Investigation of the Good" (Zen no Kenkyū).

Among the many works authored by Nishitani in Japanese, are the following titles: Divinity and Absolute Negation (Kami to zettai Mu; 1948), Examining Aristotle (Arisutoteresu ronkō; 1948); Religion, Politics, and Culture (Shūkyō to seiji to bunka; 1949); Modern Society's Various Problems and Religion (Gendai shakai no shomondai to shūkyō; 1951); Regarding Buddhism (Bukkyō ni tsuite; 1982); Nishida Kitaro: The Man and the Thought (Nishida Kitarō, sono hito to shisō; 1985); The Standpoint of Zen (Zen no tachiba; 1986); Between Religion and Non-Religion (Shūkyō to hishūkyō no aida; 1996). His written works have been edited into a 26-volume collection Nishitani Keiji Chosakushū (1986-1995). A more exhaustive list of works is accessible on the Japanese version of the present wikipage.

Collected Works [西谷啓治著作集] 26 vols. (Tokyo: Sōbunsha [創文社], 1986–95) [CW].

CW1: Philosophy of Fundamental Subjectivity, Vol. 1 [根源的主体性の哲学 正] (Tokyo: Kōbundō [弘文堂], 1940)

CW2: Philosophy of Fundamental Subjectivity, Vol. 2 [根源的主体性の哲学 続]

CW3: Studies on Western Mysticism [西洋神秘思想の研究]

CW4: Contemporary Society’s Problems and Religion [現代社会の諸問題と宗教]

CW5: Aristotle Studies [アリストテレス論考] (Tokyo: Kōbundō [弘文堂], 1948)

CW6: Philosophy of Religion [宗教哲学]

CW7: God and the Absolute Nothing [神と絶対無]

CW8: Nihilism [ニヒリズム]

CW9: Nishida’s Philosophy and Tanabe’s Philosophy [西田哲学と田辺哲学]

CW10: What Is Religion: Essays on Religion, Vol. 1 [宗教とは何か——宗教論集I] (Tokyo: Sōbunsha [創文社], 1961)

CW11: The Standpoint of Zen: Essays on Religion, Vol. 2 [禅の立場——宗教論集II] (Tokyo: Sōbunsha [創文社], 1986)

CW12: Hanshan’s Poetry [寒山詩] (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō [筑摩書房], 1986)

CW13: Philosophical Studies [哲学論考]

CW14: Lectures on Philosophy, Vol. 1 [講話 哲学I]

CW15: Lectures on Philosophy, Vol. 2 [講話 哲学II]

CW16: Lectures on Religion [講話 宗教]

CW17: Lectures on Buddhism [講話 仏教]

CW18: Lectures on Zen and Jōdo [講話 禅と浄土]

CW19: Lectures on Culture [講話 文化]

CW20: Occasional Essays, Vol. 1 [隨想I]

CW21: Occasional Essays, Vol. 2 [隨想II]

CW22: Lectures on Shōbōgenzō, Vol. 1 [正法眼蔵講話I]

CW23: Lectures on Shōbōgenzō, Vol. 2 [正法眼蔵講話II]

CW24: Lectures at Ōtani University, Vol. 1 [大谷大学講義I]

CW25: Lectures at Ōtani University, Vol. 2 [大谷大学講義II]

CW26: Lectures at Ōtani University, Vol. 3 [大谷大学講義III]

Monographs

Articles

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.