Loading AI tools

American philosopher, diplomat, and educator (1862–1947) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

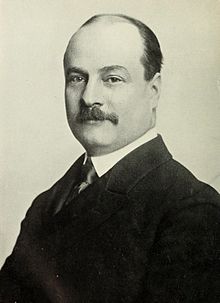

Nicholas Murray Butler (April 2, 1862 – December 7, 1947) was an American philosopher, diplomat, and educator. Butler was president of Columbia University,[1] president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, and the late James S. Sherman's replacement as William Howard Taft’s running mate in the 1912 United States presidential election. The New York Times printed his Christmas greeting to the nation for many years during the 1920s and 1930s.[2][3][4][5]

Nicholas Butler | |

|---|---|

Butler c. 1902 | |

| 12th President of Columbia University | |

| In office January 6, 1902 – October 1, 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Seth Low |

| Succeeded by | Frank D. Fackenthal (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 2, 1862 Elizabeth, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | December 7, 1947 (aged 85) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses |

|

| Education | Columbia University (BA, MA, PhD) |

| Signature |  |

Butler, great-grandson of Morgan John Rhys,[6] was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, to Mary Butler and manufacturing worker Henry Butler. He enrolled in Columbia College (later Columbia University) and joined the Peithologian Society. He earned his bachelor of arts degree in 1882, his master's degree in 1883 and his doctorate in 1884. Butler's academic and other achievements led Theodore Roosevelt to call him "Nicholas Miraculous". In 1885, Butler studied in Paris and Berlin and became a lifelong friend of future Secretary of State Elihu Root. Through Root he also met Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. In the fall of 1885, Butler joined the staff of Columbia's philosophy department.

In 1887, he co-founded with Grace Hoadley Dodge,[7] and became president of, the New York School for the Training of Teachers, which later affiliated with Columbia University and was renamed Teachers College, Columbia University, and from which a co-educational experimental and developmental unit became Horace Mann School.[8] From 1890 to 1891, Butler was a lecturer at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Throughout the 1890s, Butler served on the New Jersey Board of Education and helped form the College Entrance Examination Board. During the 1890s Butler edited The Great Educators book series for Charles Scribner's Sons.[9]

In 1901, Butler became acting president of Columbia University and, in 1902, formally became president. Among the many dignitaries in attendance at his investiture was President Roosevelt. Butler was president of Columbia for 43 years, the longest tenure in the university's history, retiring in 1945. As president, Butler carried out a major expansion of the campus, adding many new buildings, schools, and departments. These additions included Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, the first academic medical center in the world.

In 1919, Butler amended the admissions process to Columbia in order to limit the number of Jewish students (it became the first American institution of higher learning to establish an anti-Jewish quota). Butler's policy was successful and the number of students hailing from New York City dropped from 54% to 23% stemming "the invasion of the Jewish student".[10][11] This is one of the reasons why Butler has been called an anti-semite.[12]

In September 1931, Butler told the freshman class at Columbia that totalitarian systems produced "men of far greater intelligence, far stronger character, and far more courage than the system of elections."[13]: 204

In 1937, he was admitted as an honorary member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati.[14]

In 1941, the Pulitzer Prize fiction jury selected Ernest Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls. The Pulitzer Board initially agreed with that judgment, but Butler, ex officio head of the Pulitzer board, found the novel offensive and persuaded the board to reverse its determination, so that no novel received the prize that year.[15]

During his lifetime, Columbia named its philosophy library for him; after he died, its main academic library, previously known as South Hall, was rechristened Butler Library. A faculty apartment building on 119th Street and Morningside Drive was also renamed in Butler's honor, as was a major prize in philosophy.

A polemical attack on Butler's time at Columbia University appeared in The Goose-Step: A Study of American Education, by Upton Sinclair.

Butler was a delegate to each Republican National Convention from 1888 to 1936; when Vice President James S. Sherman died six days before the 1912 United States presidential election, Butler was designated to receive the electoral votes that Sherman would have received: the Republican ticket won only 8 electoral votes from Utah and Vermont, finishing third behind the Democrats and the Progressives. Butler tried to secure the 1916 Republican presidential nomination for Elihu Root. Butler also sought the nomination for himself in 1920, without success.[16]

Butler believed that Prohibition was a mistake, with negative effects on the country. He was active in the successful effort for Repeal Prohibition in 1933.[17]

He credited John W. Burgess along with Alexander Hamilton for providing the philosophical basis of his Republican principles.[18]

In June 1936, Butler traveled to the Carnegie Endowment Peace Conference in London where, at the meeting, fundamental problems of money and finance were explored.[19]

According to historian Stephen H. Norwood, Butler failed to "grasp the nature and implications of Nazism... influenced both by his antisemitism, privately expressed, and his economic conservatism and hostility to trade unionism."[20] Butler was a longtime admirer of Benito Mussolini. He compared the Italian Fascist leader to Oliver Cromwell[21] and, in the 1920s, he noted "the stupendous improvement which Fascism has brought".[22]

In November 1933, months after the Nazi book burnings began, he welcomed Hans Luther, the German ambassador to the United States, to Columbia and refused to appear with a notable German dissident when the latter visited the university. Butler was criticized for his "remarkable silence" and complicity towards Hitler's regime until the late 1930s.[12][23]

From 1907 to 1912, Butler was the chair of the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration. Butler was also instrumental in persuading Andrew Carnegie to provide the initial $10 million funding for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Butler became head of international education and communication, founded the European branch of the Endowment headquartered in Paris, and was President of the Endowment from 1925 to 1945. For his work in this field, he received the Nobel Peace Prize for 1931 (shared with Jane Addams) "[For his promotion] of the Kellogg-Briand pact" and for his work as the "leader of the more establishment-oriented part of the American peace movement".

In December 1916, Butler, Roosevelt and other philanthropists, including Scottish-born industrialist John C. Moffat, William Astor Chanler, Joseph Choate, Clarence Mackay, George von Lengerke Meyer, and John Grier Hibben, purchased the Château de Chavaniac, birthplace of the Marquis de Lafayette in Auvergne, to serve as a headquarters for the French Heroes Lafayette Memorial Fund,[24][25] which was managed by Chanler's ex-wife, Beatrice Ashley Chanler.[26][27]

Butler was President of the Pilgrims Society, which promotes Anglo-American friendship.[28] He served as President of the Pilgrims from 1928 to 1946.[29] Butler was president of The American Academy of Arts and Letters from 1928 to 1941[citation needed][30] and was an early member of the academy.[31]

Butler married Susanna Edwards Schuyler (1863–1903) in 1887 and had one daughter from that marriage. Susanna was the daughter of Jacob Rutsen Schuyler (1816–1887) and Susannah Haigh Edwards (born 1830). His wife died in 1903 and he married again in 1907 to Kate La Montagne, granddaughter of New York property developer Thomas E. Davis.[32]

In 1940, Butler completed his autobiography with the publication of the second volume of Across the Busy Years.[33]

Butler became almost completely blind in 1945 at age 83. He resigned from the posts he held and died two years later.[34] He is interred at Cedar Lawn Cemetery, in Paterson, New Jersey.[citation needed]

Butler was not universally liked. In 1939, a former student of Butler, Rolfe Humphries, published in the pages of Poetry an effort titled "Draft Ode for a Phi Beta Kappa Occasion" that followed a classical format of unrhymed blank verse in iambic pentameter with one classical reference per line. The first letters of each line of the resulting acrostic spelled out the message: "Nicholas Murray Butler is a horses [sic] ass". Upon discovering the "hidden" message, the irate editors ran a formal apology.[35] Randolph Bourne lampooned Butler as "Alexander Macintosh Butcher" in "One of our Conquerors", a 1915 essay he published in The New Republic.[36]

Butler wrote and spoke voluminously on all manner of subjects ranging from education to world peace. Although marked by erudition and great learning, his work tended toward the portentous and overblown. In The American Mercury, the critic Dorothy Dunbar Bromley referred to Butler's pronouncements as "those interminable miasmas of guff".[37]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.