Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Prehistory of France

Paleolithic to Iron Age prehistory of France From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Prehistoric France is the period in the human occupation (including early hominins) of the geographical area covered by present-day France which extended through prehistory and ended in the Iron Age with the Roman conquest, when the territory enters the domain of written history.

The Pleistocene is characterized by long glacial periods accompanied by marine regressions, interspersed at more or less regular intervals by milder but shorter interglacial stages. Human populations during this period consisted of nomadic hunter-gatherers. Several human species succeeded each other in the current territory of France until the arrival of modern humans in the Upper Palaeolithic .

The earliest known fossil man is Tautavel Man, dating from 570,000 years ago. Neanderthal Man is attested in France from about 335,000 years before present. Homo sapiens, modern humans, are attested since around 54,000 years ago in the Mandrin Cave.[1][2]

In the Neolithic, which begins in the south of France in the middle of the 6th millennium BC, the first farmers appeared. The first megaliths were erected in the early 5th millennium BC.

Remove ads

The Palaeolithic

Summarize

Perspective

Lower Palaeolithic

The Lower Paleolithic period began with the first human occupation of the region. Stone tools discovered at Lézignan-la-Cèbe indicate that early humans were present in France from least 1.57 million years ago.[3]

5 prehistoric sites in France are dated from between 1 and 1.2 million years ago:[4]

- the Bois-de-Riquet, in Lézignan-la-Cèbe, in the Hérault (1.2 Ma), discovered in 2008

- the Vallonnet cave, in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, in the Alpes-Maritimes (1.15 Ma), discovered in 1958

- Terre-des-Sablons, in Lunery-Rosières, in Cher (1.15 Ma),

- Pont-de-Lavaud, at Éguzon-Chantôme, in Indre (1.05 Ma),

- Pont-de-la-Hulauderie, in Saint-Hilaire-la-Gravelle, in Loir-et-Cher (1 My).

None of these sites have thus far revealed any evidence of lithic industry which prevents identification of the human species responsible for them.[4]

France includes Olduwan (Abbevillian) and Acheulean sites from early or non-modern (transitional) Hominini species, most notably Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis. Tooth Arago 149 - 560,000 years. Tautavel Man (Homo erectus tautavelensis), is a proposed subspecies of the hominid Homo erectus, the 450,000-year-old fossil remains of whom were discovered in the Arago cave in Tautavel.

The Grotte du Vallonnet near Menton contained simple stone tools dating to 1 million to 1.05 million years BC.[5] Cave sites were exploited for habitation, but the hunter-gatherers of the Palaeolithic era also possibly built shelters such as those identified in connection with Acheulean tools at Grotte du Lazaret and Terra Amata near Nice in France. Excavations at Terra Amata found traces of the earliest known domestication of fire in Europe, from 400,000 BC.[5]

Middle Palaeolithic

The Neanderthals are thought to have arrived earlier than 300,000 BC,[a] but seem to have died out by about by 30,000 BC, presumably unable to compete with modern humans during a period of cold weather. Numerous Neanderthal, or "Mousterian", artifacts (named after the type site of Le Moustier, a rock shelter in the Dordogne region of France) have been found from this period, some using the "Levallois technique", a distinctive type of flint knapping developed by hominids during the Lower Palaeolithic but most commonly associated with the Neanderthal industries of the Middle Palaeolithic. Importantly, recent findings suggest that Neanderthals and modern humans may have interbred.[7]

Important Mousterian sites are found at:

- Fieux, in Lot-et-Garonne (340 ka) [8]

- Petit-Bost, in the Dordogne (325 ka)[9]

The first identified Neanderthal burials were discovered at La Chapelle-aux-Saints in 1908 (dating from 70 ka) then at La Ferrassie in 1909.[10] The identification of burial practices in Neanderthals at these sites led to new insights concerning the capacity of Neanderthals to develop spiritual or metaphysical beliefs,[11] extending understanding of the human species beyond what had been hitherto assumed.[12]

Upper Palaeolithic

The earliest indication of Upper Palaeolithic early modern human (formerly referred to as Cro-Magnon) migration into France, and indeed in the whole of Europe, is a series of modern human teeth with Neronian industry stone tools found at Grotte Mandrin Cave, Malataverne in France, dated in 2022 to between 56,800 and 51,700 years ago. The Neronian is one of the many industries associated with modern humans classed as transitional between the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic.[13] When they arrived in Europe, they brought with them sculpture, engraving, painting, body ornamentation, music and the painstaking decoration of utilitarian objects. Some of the oldest works of art in the world, such as the cave paintings at Lascaux in southern France, are datable to shortly after this migration.[14]

European Palaeolithic cultures are divided into several chronological subgroups (the names are all based on French type sites, principally in the Dordogne region):[15]

Remove ads

- Aurignacian (c. 38,000 - 23,000 BP) – responsible for Venus figurines, cave paintings at the Chauvet Cave (continued during the Gravettian period).

- Périgordian (c. 35,000 - 20,000 BP) – use of this term is being debated (the term implies that the following subperiods represent a continuous tradition).

- Châtelperronian (c. 39,000 - 29,000 BP) – culture derived from the earlier, Neanderthal, Mousterian industry as it made use of Levallois cores and represents the period when Neanderthals and modern humans occupied Europe together.

- Gravettian (c. 28,000 - 22,000 BP) – responsible for Venus figurines, cave paintings at the Cosquer Cave.

- Solutrean (c. 22,000 - 17,000 BP)

- Magdalenian (c. 17,000 - 10,000 BP) – thought to be responsible for the cave paintings at Pech Merle (in the Lot in Languedoc, dating back to 16,000 BC), Lascaux (located near the village of Montignac, in the Dordogne, dating back to somewhere between 13,000 and 15,000 BC, and perhaps as far back as 25,000 BC), the Trois-Frères cave and the Rouffignac Cave also known as The Cave of the hundred mammoths. It possesses the most extensive cave system of the Périgord in France with more than 8 kilometers of underground passageways.

- Chauvet cave painting, Aurignacian culture

- Venus of Brassempouy, Gravettian culture

- Inscribed bones, Gravettian culture

- Lascaux cave painting, Magdalenian culture

- Lascaux cave painting, Magdalenian culture

- Stone engraving, Magdalenian culture

- Bone sculpture, Magdalenian culture

- Large biface, Solutrean culture

- Magdalenian tent, 12,000 BP

Remove ads

The Mesolithic

Summarize

Perspective

From the Paleolithic to the Mesolithic, the Magdalenian culture evolved. The Early Mesolithic, or Azilian, began about 14,000 years ago, in the Franco-Cantabrian region of northern Spain and Southern France. This was ahead of other parts of Western Europe, where the Mesolithic began by 11,500 years ago at the beginning of the Holocene. It ended with the introduction of farming.[17]

Remove ads

The Azilian culture of the Late Glacial Maximum co-existed with similar early Mesolithic European cultures such as the Tjongerian of North-Western Europe, the Ahrensburgian of Northern Europe and the Swiderian of North-Eastern Europe, all succeeding the Federmesser complex. The Azilian culture was followed by the Sauveterrian in Southern France and Switzerland, the Tardenoisian in Northern France, the Maglemosian in Northern Europe.[18]

Remove ads

Archeologists are unsure whether Western Europe saw a Mesolithic immigration. Populations speaking non-Indo-European languages are obvious candidates for Mesolithic remnants. The Vascons (Basques) of the Pyrenees present the strongest case, since their language is related to none other in the world, and the Basque population has a distinct genetic profile.[19] The disappearance of Doggerland affected the surrounding territories and the hunter gatherers living there are believed to have migrated to northern France and as far as eastern Ireland to escape from the floods.[20]

The Neolithic

Summarize

Perspective

The Neolithic period lasted in northern Europe for approximately 3,000 years (c. 5000 BC–2000 BC). It is characterised by the so-called Neolithic Revolution, a transitional period that included the adoption of agriculture, the development of tools and pottery (Cardium pottery, LBK), and the growth of larger, more complex settlements. There was an expansion of peoples from southwest Asia into Europe; this diffusion across Europe, from the Aegean to Britain, took about 2,500 years (6500 BC–4000 BC).[21] According to the leading Kurgan hypothesis, Indo-European languages were introduced to Europe later, during the succeeding Bronze Age, and Neolithic peoples in Europe are called "Pre-Indo-Europeans" or "Old Europe". Nevertheless, some archaeologists believe that the Neolithic expansion, and the eclipse of Mesolithic culture, coincided with the introduction of Indo-European speakers.[22] In what is known as the Anatolian hypothesis, it is postulated that Indo-European languages arrived in the early Neolithic. Old European hydronymy is taken by Hans Krahe to be the oldest reflection of the early presence of Indo-European languages in Europe.

Many European Neolithic groups share basic characteristics, such as living in small-scale family-based communities, subsisting on domestic plants and animals supplemented with the collection of wild plant foods and with hunting, and producing hand-made pottery (that is made without the potter's wheel).[citation needed] Archeological sites from the Neolithic in France include artifacts from the Linear Pottery culture (c. 5500 – c. 4500 BC), the Rössen culture (c. 4500—4000 BC), and the Chasséen culture (4,500 - 3,500 BC; named after Chassey-le-Camp in Saône-et-Loire), the name given to the late Neolithic pre-Beaker culture that spread throughout the plains and plateaux of France, including the Seine basin and the upper Loire valleys.[citation needed]

The 'Armorican' (Castellic culture) and Northern French Neolithic (Cerny culture) is based on traditions of the Linear Pottery culture or "Limburg pottery" in association with the La Hoguette/Cardial culture. The Armorican culture may also have origins in the Mesolithic tradition of Téviec and Hoedic in Brittany.[23]

It is most likely from the Neolithic that date the megalithic (large stone) monuments, such as the dolmens, menhirs, stone circles and chamber tombs, found throughout France, the largest selection of which are in the Brittany and Auvergne regions. The most famous of these are the Carnac stones (c. 3300 BC, but may date to as old as 4500 BC) and the stones at Saint-Sulpice-de-Faleyrens.[24]

- Cairn of Barnenez, Brittany, c. 4800 BC

- Turquoise necklace, Carnac, 4500 BC

- Polished jade axes, Carnac, c. 4500 BC

- Polished jade rings, Carnac, c. 4500 BC

- Stele, Chasséen culture, 4th millennium BC.[c]

- Linear Pottery culture longhouse, c. 5000 BC

- Ceramics from Fontbouisse, c. 3000 BC

- Gold diadem, jade axe and boar's tusk pectoral, Pauilhac, c. 3500 BC

- Locmariaquer megaliths, c. 4500 BC

- Champ Durand fortifications, c. 3400 BC

- Tumulus of Bougon, c. 4700 BC

- Table des Marchand, c. 4000 BC

- Dolmen de Bagneux, c. 4000-3000 BC

- Tumulus of Colombiers-sur-Seulles, France, 5th mill. BC

Remove ads

The Copper Age

Summarize

Perspective

During the Chalcolithic or Copper Age, a transitional age from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age, France shows evidence of the Seine-Oise-Marne culture and the Beaker culture.

The Seine-Oise-Marne culture or "SOM culture" (c. 3100 to 2400 BC) is the name given by archaeologists to the final culture of the Neolithic in Northern France around the Oise River and Marne River. It is most famous for its gallery grave megalithic tombs which incorporate a port-hole slab separating the entrance from the main burial chamber. In the chalk valley of the Marne River rock-cut tombs were dug to a similar design. In the Southeast, several groups whose culture had evolved from Chasséen culture also built megaliths.[27]

Beginning about 2600 BC, the Artenacian culture, a part of the larger European Megalithic Culture, developed in Dordogne, possibly as a reaction to the advance of Danubian peoples (such as SOM) over Western France. Armed with typical arrows, they took over all Atlantic France and Belgium by 2400 BC, establishing a stable border with the Indo-Europeans (Corded Ware) near the Rhine that would remain stable for more than a millennium.[citation needed]

The Bell Beaker culture (c. 2800–1900 BC) was a widespread phenomenon that expanded over most of France, excluding the Massif Central, in the third and early second millennia BC.[citation needed]

- Remains of a large building at Challignac, Artenacian culture

- Remove adsCopper axe, Brittany, 3rd millennium BC[28]

- Bell Beaker, c. 2500 BC

- Flint arrowheads, Bell Beaker culture

- Copper daggers, Bell Beaker culture

- Gold lunulas, Brittany, Bell Beaker culture

- Illustration of a Bell Beaker wagon

- The Bell Beaker culture had domesticated horses.[29]

- Burial mound, Brittany

Remove ads

The Bronze Age

Summarize

Perspective

In the Kurgan Hypothesis, Indo-European languages spread to Europe in the Bronze Age. The culture of the Kurgans is also known as Yamnaya Culture and recent results from acheaogenetics have linked this culture with genetic ancestry components of the Western Steppe Herders, and it has been possible to reconstruct migrations of these people across Europe co-extensive with the arrival of the Yamnaya and Corded Ware cultures.[citation needed]

In France, the first studies on the Bronze Age date from the 19th century. The "Manuel d'archéologie préhistorique, celtique et gallo-romaine," (Manual of Prehistoric, Celtic and Gallo-Roman Archaeology), by Joseph Déchelette, published in 1910, was for a long time the reference for the study of this period.[30] In the 1950s, Jean-Jacques Hatt proposed a subdivision of the French Bronze Age, and in 1958 he published a tripartate division.[31] This model divided the Bronze Age into three parts, Early Bronze, Middle Bronze and Late Bronze Age and serves as a reference for the majority of subsequent studies on the Bronze Age in France.[32]

The Bronze Age archeological cultures in France include the transitional Beaker culture (c. 2800–1900 BC), the Early Bronze Age Rhône culture (c. 2300-1600 BC) and Armorican Tumulus culture (c. 2200 – c. 1400 BC), the Middle Bronze Age Tumulus culture (c. 1600-1200 BC), and the Late Bronze Age Atlantic Bronze Age (c. 1300 – c. 700 BC) and Urnfield culture (c. 1300-800 BC). Early Bronze Age sites in Brittany (Armorican Tumulus culture) are believed to have grown out of Beaker roots, with some Wessex culture and Unetice culture influence. Some scholars think that the Urnfield culture represents an origin for the Celts as a distinct cultural branch of the Indo-European family (see Proto-Celtic). This culture was preeminent in central Europe during the late Bronze Age; the Urnfield period saw a dramatic increase in population in the region, probably due to innovations in technology and agricultural practices.[citation needed]

Some archeologists date the arrival of several non-Indo-European peoples to this period, including the Iberians in southern France and Spain, the Ligures on the Mediterranean coast, and the Vascons (Basques) in southwest France and Spain.[citation needed]

- Bronze dagger, Rhône culture, c. 2000 BC

- Tumulus culture ceramics

- Remove adsGold vessels, Tumulus culture, c. 1400 BC

- Bronze cuirasses, Urnfield culture, 900 BC

- Bronze helmets, Urnfield culture, 1100-900 BC

- Urnfield culture artefacts

- Model of a fortification wall, Urnfield culture

- Fort Harrouard hillfort, Middle-Late Bronze Age

- Model of a Middle Bronze Age house

- Bronze pins and ornaments, Urnfield culture, c. 1000 BC

- Urnfield culture warrior, reconstruction

- Atlantic Bronze Age, gold belt, 1300-1150 BC

- Plougrescant sword, Atlantic Bronze Age, c. 1300 BC

Remove ads

The Iron Age

Summarize

Perspective

The spread of iron-working led to the development of the Hallstatt culture (c. 700 to 500 BC) directly from the Urnfield. Proto-Celtic, the latest common ancestor of all known Celtic languages, is generally considered to have been spoken at the time of the late Urnfield or early Hallstatt cultures, in the early 1st millennium BC.[36]

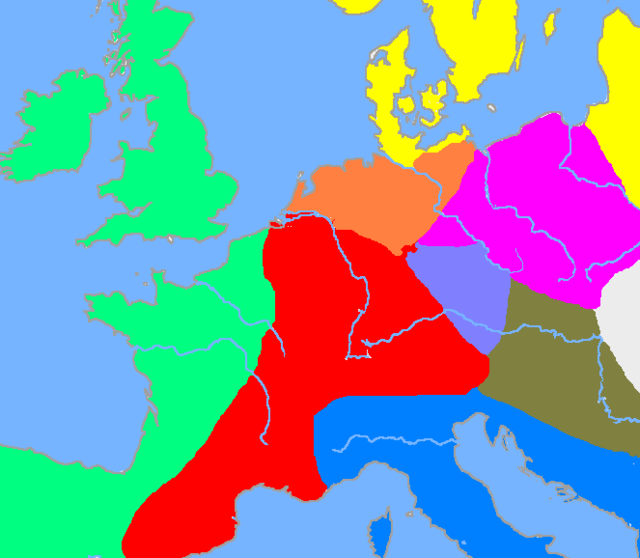

The Hallstatt culture was succeeded by the La Tène culture, which developed out of the Hallstatt culture without any definite cultural break, under the impetus of considerable Mediterranean influence from Greek, and later Etruscan civilizations. The La Tène culture developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC) in eastern France, Switzerland, Austria, southwest Germany, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. Farther to the north extended the contemporary Pre-Roman Iron Age culture of Northern Germany and Scandinavia.[36][37]

In addition, Greeks and Phoenicians settled outposts like Marseille in this period (c. 600 BC).[38]

By the 2nd century BC, Celtic France was called Gaul by the Romans, and its people were called Gauls. The people to the north (in what is present-day Belgium) were called Belgae (scholars believe this may represent a mixture of Celtic and Germanic elements) and the peoples of the south-west of France were called the Aquitani by the Romans, and may have been Celtiberians or Vascons.[citation needed]

- Vix palace, Hallstatt culture, 500 BC

- Vix grave, wagon burial reconstruction, Hallstatt culture, 500 BC

- Cult wagon, Hallstatt culture, 750 BC

- Swords, La Tène culture

- Painted pottery, La Tène culture

- Chariot mounts from Somme-Bionne, La Tène culture

- Basse Yutz flagons, La Tène culture, 450 BC

- Chariot fitting, La Tène culture

- Chariot burial, La Tène culture

- Bibracte oppidum, outer walls, La Tène culture

- Gallic farm at Verberie, La Tène culture

- Murus Gallicus, c. 100 BC, La Tène culture

- Corent oppidum, La Tène culture

- Settlement at Arles, c. 2nd century BC

- Statue from Roquepertuse, 3rd-2nd century BC

Remove ads

Timeline

Summarize

Perspective

Prehistoric and Iron Age France - all dates are BC

- 1,800,000 (Date not considered secure) : Appearance of stone tools (possibly by Homo erectus) in France (Chilhac, Haute-Loire).[39]

- 1,570,000: Stone tools at Lézignan-la-Cèbe.[3]

- 1,050,000 to 1,000,000: stone tools at Grotte du Vallonnet, near Menton.[5]

- 900,000: Beginning of Günz glaciation.[40]

- 700,000: Oldest shaped tools in Brittany.

- 600,000: Beginning of Günz-Mindel interglacial.[40] Appearance of Homo heidelbergensis in Europe.

- 450,000: "Tautavel man" (possibly Homo heidelbergensis).

- 410,000: Beginning of Mindel glaciation (Mindel I).[40] Abbevillian culture, taming of fire.

- 400,000: Mindel II. Shards of "proto-Levallois" tools.

- 400,000 to 380,000: Traces of first domestication of fire at Terra Amata (Nice).

- 300,000: Beginning of Mindel-Riss interglacial.[40]

- 300,000: Appearance of Neanderthals in Europe.[6]

- 200,000: Beginning of Riss glaciation.[40]

- 130,000: Beginning of Riss-Würm interglacial.[40]

- 70,000: Beginning of Würm glaciation.[40]

- 62,000: Würm I/II interglacial.[40]

- 57,000: Brorup interglacial.[40]

- 55,000: Würm II.[40]

- 40,000: Laufen interglacial.[40] Arrival of first modern humans (Cro-Magnons) in Europe.

- 35,000: Würm IIIa.[40] Châtelperronian culture.

- 33,000: Mask of la Roche-Cotard, a Mousterian artefact.

- 32,000: Aurignacian culture.[15]

- 30,000: First statuettes and engravings in France. Disappearance of Neanderthals.

- 28,000: Arcy interglacial.[citation needed]

- 27,500: Würm IIIb.[40]

- 25,000: Paudorf interglacial.

- 23,000: Würm IIIc.[40]

- 18,000: End of Würm glaciation.[40]

- 18,692: Beginning of Solutrean culture.

- 16,000: Cold spell (Oldest Dryas).

- 15,000: Magdalenian culture.[18]

- 15,300: Lascaux.[18]

- 14,500: Middle Magdalenian. Bølling Oscillation.[18]

- 14,100: Cold spell (Older Dryas).

- 14,000: Allerød Oscillation.

- 13,500: Upper Magdalenian.[18]

- 13,000: Hamburg culture[18]

- 10,300: Cold spell (Younger Dryas).

- 9500: Beginning of Holocene.

- 7000: Domestication of the sheep.

- 6900: Domestication of the dog.

- 5000: Appearance of Linear Pottery culture in France.[citation needed]

- 4650: Oldest neolithic village in France, Courthézon in the Vaucluse.[citation needed]

- 4000: Neolithic Chasséen culture village of Bercy.[citation needed]

- 3610: Appearance of first megaliths in France.[24]

- 3430: Chasséen culture village of Saint-Michel du Touch near Toulouse.[citation needed]

- 3430: Appearance of Rössen culture at Baume de Gonvilla in Haute-Saône.[citation needed]

- 3250: Expansion of Chasséen culture in the south of France, from the Lot to the Vaucluse.[citation needed]

- 3190: Chasséen culture in Calvados.[citation needed]

- 2530: Chasséen culture in Pas-de-Calais.[citation needed]

- 2450: End of Chasséen culture in Eure-et-Loir.[citation needed]

- 2400: End of Chasséen culture in Saint-Mitre (in Reillanne, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence).[citation needed]

- 2300: Village at Ponteau (in Martigues, Provence) of the Beaker culture.[citation needed]

- 1800: Beginning of Bronze Age in France.[30]

- 800: Appearance in France, via the Rhine and the Moselle, and expanding into Champagne and Bourgogne of the Urnfield culture.[36]

- 725: Beginning of Hallstatt culture.[36]

- 680: Founding of Antibes, the first Greek colony in France.[38]

- 600: Founding of Massalia (future Marseille) by the Greeks from the Ionian city of Phocaea.[38]

- 450: The Celts of la Tène appear in Champagne. They expand to the Garonne, forming what will come to be called the Gaul civilization.[38]

- 390: The Celtic chief Brennus sacks Rome.[38]

- 121: Roman occupation of Gallia Narbonensis.[38]

- 118: Founding of the Roman colony Narbo Martius (future Narbonne).[38]

- 58-51: Conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar.[38]

See also

Notes

- The oldest known Neanderthal fossil in France was found in 1998 in the cave of Pradayrol, in Caniac-du-Causse, in Lot-et-Garonne. A Neanderthal incisor has been dated there to 335,000 years.[6]

- The engraving on the Thaïs bone is a non-decorative notational system of considerable complexity. The cumulative nature of the markings together with their numerical arrangement and various other characteristics strongly suggest that the notational sequence on the main face represents a non-arithmetical record of day-by-day lunar and solar observations undertaken over a time period of as much as 3½ years. The markings appear to record the changing appearance of the moon, and in particular its crescent phases and times of invisibility, and the shape of the overall pattern suggests that the sequence was kept in step with the seasons by observations of the solstices. The latter implies that people in the Azilian period were not only aware of the changing appearance of the moon but also of the changing position of the sun, and capable of synchronizing the two. The markings on the Thaïs bone represent the most complex and elaborate time-factored sequence currently known within the corpus of Palaeolithic mobile art. The artefact demonstrates the existence, within Upper Palaeolithic (Azilian) cultures c. 12,000 years ago, of a system of time reckoning based upon observations of the phase cycle of the moon, with the inclusion of a seasonal time factor provided by observations of the solar solstices.[16]

- Provence stelae with chevron ornamentation are relatively well dated. They have always been dated to the Middle Neolithic, and more exactly to the Late Chasséen.[26]

- The technostylistic origin of the swords of Tréboul and Le Cheylounet types has been widely debated elsewhere. For the former, J. Briard (1965) favoured an evolution from the Armorican Tumulus daggers; for the latter, J.P. Daugas and D. Vuaillat (2009) highlight a Unétician tradition, but the strong technostylistic kinship between the two sword types suggests a complex interplay of influences. Their chronological position is clearly established: Middle Bronze Age 1, from about 1550 to 1450 BC according to the latest available chronological details. (Translated from French).[33]

Remove ads

References

Sources

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads