William Gerald Douglas[1] (17 April 1934 – 18 June 1991) was a Scottish film director best known for the trilogy of films about his early life.

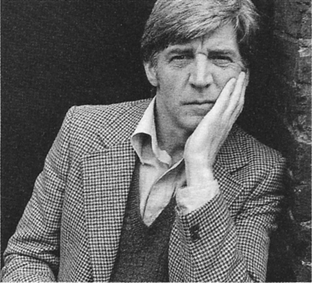

Bill Douglas | |

|---|---|

Photo by Jane Bown, 1979 | |

| Born | 17 April 1934 Newcraighall, Scotland |

| Died | 18 June 1991 (aged 57) Barnstaple, Devon, England |

| Alma mater | London Film School |

| Years active | 1972–1990 |

Biography

Born in Newcraighall, a mining village on the outskirts of Edinburgh. He was brought up initially by his maternal grandmother, Jean Beveridge; following her death, he lived with his father and paternal grandmother. He undertook his National Service in Egypt, where he met his lifelong friend, Peter Jewell. On returning to Britain, Douglas moved to London and began a career of acting and writing. After spending some time with Joan Littlewood's 'Theatre Workshop' company at the Theatre Royal Stratford East, he was cast in the Granada television series, The Younger Generation in 1961 and had a musical, Solo, produced in 1962 at Cheltenham.

Filmmaking career

Having been interested in film-making all his life, in 1969 Douglas enrolled at the London School of Film Technique, where he wrote the screenplay for a short autobiographical film called Jamie. After initial difficulties in finding support for the project, he eventually found a champion at the British Film Institute in the newly appointed head of Production, Mamoun Hassan,[2][3] who secured funding on the basis that Jamie should form part one of a trilogy – echoing the great childhood trilogies of Ray and Gorky. The film was renamed My Childhood, and its success on the international festival circuit paved the way for the second and third instalments of the trilogy of Douglas's formative years: My Ain Folk (1973) and My Way Home (1978).[4]

The Bill Douglas Trilogy recounts the harrowing experiences of a young boy, Jamie, growing up in material and emotional poverty with his brother and grandmother; followed by incarceration in a children's home, and then living in a hostel for down-and-outs. Eventually the call-up for national service allows Jamie to find freedom through his friendship with Robert, a young middle class Englishman who introduces him to books and the possibility of a more optimistic and fulfilling future. The austere black and white images of the films embody a stillness and intensity reminiscent of silent cinema and this visual style is augmented by the equally spare and precise use of sound. Just as the stillness of the image forces the audience to look, so the relative silence encourages greater attention to specific sounds – boots scraping on asphalt, the chirping of birds and the timbre of voices – granting an emotional power that many considered lost in the aural bombardment characterising much contemporary cinema.

The Trilogy gained a wealth of critical plaudits but Douglas struggled to raise financing for his next project, and was forced to find other ways of earning a living. Mamoun Hassan, the former head of BFI Production, invited him to teach at the National Film and Television School from 1978 and he proved to be an inspiring presence. Hassan was also able, in his role as director of the National Film Finance Corporation to help realise the project of Comrades, Douglas's film about the 'Tolpuddle Martyrs', six Dorset farm labourers who in 1834 were arrested and tried for forming a trade union and subsequently transported to Australia. Even so, the film did not appear until 1986, six years after the screenplay had been completed. Dubbed a 'poor man's epic', Comrades continues Douglas's interest in the perseverance of the human spirit in the face of material adversity. It also brings to the fore his fascination with the world of optics and image-making, through a number of references to various forms of Victorian optical entertainments such as the magic lantern, the zoetrope, the peep show and the camera obscura. The story itself is mediated by the character of an itinerant magic lanternist who reappears in a number of roles.

Comrades was to be Bill Douglas's last film. He died of cancer and is buried in the churchyard of Bishop's Tawton in Devon. He left behind him two unmade screenplays: Justified Sinner, an adaptation of James Hogg's celebrated novel The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, and Flying Horse, based on the life of pre-cinema pioneer Eadweard Muybridge. Another posthumous script, Ring of Truth, written during a fellowship to Strathclyde University in 1990, was produced by BBC Scotland in 1996.[5]

Personal life

Bill Douglas lived with Peter Jewell (on whom Robert of the Trilogy was based) for much of his life. Of their relationship, Peter Jewell said in 2006:

We weren't a gay couple. A lot of people assume that we were because [we lived] together [...] but Bill wasn't homosexual [...] we were all sorts of other things to each other. Practically everything but sexual.[6]

Legacy

Douglas's legacy was not confined to his films. Along with Peter Jewell, he was a voracious collector of books, memorabilia, and artefacts relating to the history and prehistory of cinema. This core collection formed the basis of the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum (formerly The Bill Douglas Centre for the History of Cinema and Popular Culture), housed at the University of Exeter, when it opened six years after his death. The museum contains an exhibition on Bill Douglas's life and work and holds his working papers, which can be accessed by researchers.

In 2012, the Glasgow Short Film Festival announced the inaugural Bill Douglas Award for their International Short Film Competition, named in his honour.

Filmography

As director

Student films (London Film School)

- Charlie Chaplin's London (1969)

- Striptease (1969)

- Globe (1969/70)

- Come Dancing (1970)

Feature films

- The Bill Douglas Trilogy:

- My Childhood (1972)

- My Ain Folk (1973)

- My Way Home (1978)

- Comrades (1986)

As writer

As Co-Writer:

- Home and Away (A BFI Production, directed by Michael Alexander, 1974)

Unproduced scripts:

- Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1988), based on James Hogg's 1824 novel, The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner

- Flying Horse (1990), based on the life of English photographer Eadweard Muybridge

- The Ring of Truth (1990) (Produced by BBC Scotland in 1996)[5]

Documentaries about Bill Douglas

- Arena (1979) BBC TV documentary on Douglas after he had completed the Trilogy

- Bill Douglas: On Stony Ground (1992) BBC Scotland documentary

- Bill Douglas: Intent on Getting the Image (2006) Documentary on Douglas's life and work by 400Blows Productions/Andy Kimpton-Nye

- Visions of: COMRADES (2009) by 400Blows Productions/Andy Kimpton-Nye

- Lanterna Magicka: Bill Douglas & the Secret History of Cinema (2009) Documentary on Douglas's fascination with pre-cinema optical devices, and how he integrated them into Comrades. By Sean Martin and Louise Milne

- Peter Jewell Remembers Bill Douglas (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IcV7QKPpSuQ). A documentary short on Bill Douglas, the man and his films, as remembered by his longtime friend Peter Jewell. Made in 2013 by Andy Kimpton-Nye/400Blows Productions.

- Pre-Cinema in COMRADES (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qLEgNiGAizM). Peter Jewell, Bill douglas's longtime friend, on the importance of pre-cinema artefacts in COMRADES. Made in 2014 by Andy Kimpton-Nye/400blows Productions.

- The Lanternist's Account (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lP9Ug9W-omQ). A documentary short: Alex Norton recalls playing 13 different roles in COMRADES. Made in 2014 by Andy Kimpton-Nye/400Blows Productions.

- Mamoun Hassan on the Bill Douglas Trilogy (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V0MtElXPnk0). A documentary short: former Head of the BFI Production Board, Mamoun Hassan, discusses Douglas's masterpiece, The Trilogy. Made in 2013 by Andy Kimpton-Nye/400Blows Productions.

Bill Douglas on DVD

- The Bill Douglas Trilogy (BFI, 2008, Blu-ray: 2009; in the US the trilogy was released on DVD by Facets) – Also includes Douglas's graduation film, Come Dancing, a brief 1980 interview with Douglas, and Andy Kimpton-Nye's documentary.

- Comrades (BFI, also Blu-ray, 2009) – Also includes Home and Away, Martin/Milne's Lanterna Magicka, and interviews with Bill Douglas from 1978 and the Comrades shoot.

References

External links

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.