Murujuga

Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

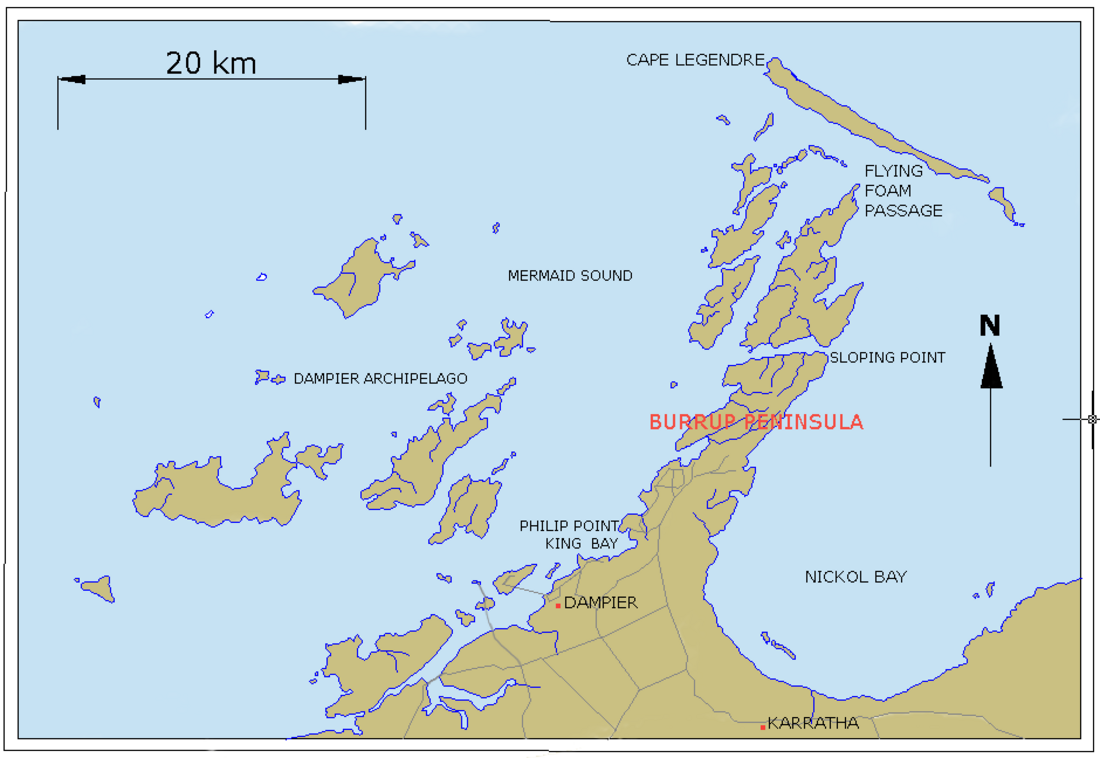

Murujuga, formerly known as Dampier Island and today usually known as the Burrup Peninsula, is an area in the Dampier Archipelago, in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, containing the town of Dampier. The Dampier Rock Art Precinct, which covers the entire archipelago, is the subject of ongoing political debate due to historical and proposed industrial development. Over 40% of Murujuga lies within Murujuga National Park, which contains within it the world's largest collection of ancient 40,000 year old[1] rock art (petroglyphs).

The region is sometimes confused with the Dampier Peninsula, 800 kilometres (500 mi) to the north-east.

Description of rock art

Most Murujuga rock art is on 2.7 billion year old igneous rocks. The rock art was made by etching away the outer millimetres of red-brown iron oxide, exposing pale centimetre-thick weathered clay. The underneath very hard igneous rock is dark grey-green coloured, and composed of granophyre, gabbo, dolerite, and granite.[2]

History and toponymy

The traditional owners of the Murujuga are an Aboriginal nation known as the Yaburara (Jaburara) people.[3] In Ngayarda languages, including that of the Yaburara, murujuga means "hip bone sticking out".[4] Between February and May 1869 a great number of Yaburara people were killed in an incident known as the Flying Foam Massacre.[3] The five clans who took over the care of the land as traditional custodians following the massacre include Yaburara, Ngarluma, Mardudhunera, Yindjibarndi and Wong-Goo-Tt-Oo peoples.[5][6][7]

First given the English name Dampier Island after the English navigator William Dampier (1651–1715), it was then an island lying 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) off the Pilbara coast. In 1963 the island became an artificial peninsula when it was connected to the mainland by a causeway for a road and railway. In 1979 Dampier Peninsula was renamed Burrup Peninsula after Mt Burrup, the highest peak on the island, which had been named after Henry Burrup, a Union Bank clerk murdered in 1885 at Roebourne.[8][9][10]

Development vs heritage protection

Summarize

Perspective

The peninsula is a unique ecological and archaeological area since it contains the Murujuga cultural landscape, the world's largest and most important collection of petroglyphs. Some of the Aboriginal rock carvings have been dated to more than 45,000 years old. The collection of standing stones here is the largest in Australia with rock art petroglyphs numbering over one million, many depicting images of the now extinct thylacine (Tasmanian tiger).[11] Dampier Rock Art Precinct covers the entire archipelago, while the Murujuga National Park lies within Burrup.[12]

Concern around the ecological, historical, cultural and archaeological significance of the area has led to a campaign for its protection, causing conflict with industrial development on the site. The preservation of the Murujuga monument has been called for since 1969, and in 2002 the International Federation of Rock Art Organizations commenced a campaign to preserve the remaining monument. Murujuga has been listed in the National Trust of Australia Endangered Places Register[13] and in the 2004, 2006, and 2008 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund.[14]

About 900 sites, or 24.4 percent of the rock art on Murujuga, had been destroyed to make way for industrial development between 1963 and 2006.[15] The Western Australian government argued for a much lower figure, suggesting that only 4 percent of sites, representing approximately 7.2 percent of petroglyphs, had been destroyed since 1972,[16][better source needed] citing the lack of a complete inventory of rock art in the region[17] as making assessments a challenging task.

In 1996, a land use plan by the Burrup Peninsula Management Advisory Board divided the region into two areas:

- a Conservation, Heritage and Recreation Area, spanning 5,400 hectares (13,000 acres), 62% of Murujuga

- an Industrial Area with an emphasis on port sites and strategic industry, 38% of Murujuga

While the plan commented upon "the value of the Northern Burrup for the preservation of its renowned Aboriginal heritage and environmental values", no comment was made on the amount of rock art affected by development and recreational activities.[18]

In 1998, the Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi people had a joint native title claim which included the Murujuga cultural landscape. The North West Shelf Joint Venture, which includes the Karratha Gas Plant, subsequently entered into a land access agreement with the Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi people. The Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi people established the Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi Foundation Limited (NYFL). Since 2000, NYFL has been the traditional owner representative organisation for the North West Shelf area. The 1998 agreement with the Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi people is largely considered to be outdated and fails to meet accepted standards for industry agreements with traditional owners.[citation needed]

Work commissioned by the National Trust of Western Australia led it to nominate the site for the National Trust Endangered Places list in 2002.[19] In 2004, funding was provided by American Express through the World Monuments Fund for further research and advocacy to be undertaken, with the goal of achieving national heritage status for the site. In 2006 the Australian Heritage Council advised the federal Environment and Heritage Minister that the site was suitable for listing on the National Heritage List.[20]

The Western Australian state government continued to support development at the site, arguing a lack of cost-effective alternative sites and that geographical expansion of facility areas would be extremely limited. Former conservative party Resources Development Minister Colin Barnett temporarily supported campaigns to save rock art in this area.[21]

The Australian federal government was divided on the issue. One reason to support site protection is that national heritage bodies support protection for the area, and the governments at national and state level have been of opposing political parties. On the other hand, the government was reluctant to interfere with the economic prosperity generated by the Western Australian economy.[22]

The protest campaign against development garnered popular support:[23]

42,000 personal messages were lodged with Woodside's Directors at their Annual General Meeting. Following shareholders questions at the AGM, Director Don Voelte finally admitted that the State Government had directed them towards developing amidst the rock art and that they had accepted.

The debate continued as of June 2007, with no intervention made by the Australian government. The federal minister indicated support for National Heritage listing, but the question of site boundaries and management strategies was still under negotiation.[24] The site was heritage-listed in the Australian national heritage in 2007.[25]

On 7 July 2008, the Australian Government placed 90% of the remaining rock art areas of the Dampier Archipelago on the National Heritage List. Campaigners continued to demand that the Australian Government include all of the undisturbed areas of the Dampier Archipelago on the World Heritage List. According to the Philip Adams radio show on Radio National, one worker on the site, an electrician for Woodside claimed the company had crushed 10,000 petroglyphs for road fill, at a time of international outrage over the Taliban destruction of the Bamiyan buddhas. The oldest representation of a human face was also destroyed. The rock pools were filled with green scum, the eucalypts of the area dying, the fluming of escaping natural gas, from faulty piping, rises as high as a six-storey building and burns the equivalent of the entire annual emissions in New Zealand, every day.[26]

In February 2009, the state government released a report finding that industry emissions did not damage the rock art.[27] WA Greens Senator Rachel Siewart criticised Premier Colin Barnett for reversing his previous support for protecting the rock art.[28]

As of 2011, the area remained on the World Monument Fund's list of 100 Most Endangered Places in the World - the only such site in Australia - because of continued mismanagement of the heritage and conservation values of the Burrup.[29]

In January 2020, the Australian Government lodged a submission for the Murujuga cultural landscape to be included as an Australian entry to the World Heritage Tentative List.[30][31][32]

In November 2021, around 50 local people rallied at Karratha to protest against one of the biggest oil and gas developments ever undertaken in Australia, by Woodside Petroleum and BHP, known as the Scarborough project[33] (Scarborough being the name of the gas field, 375 km (233 mi) off the Pilbara coast[34][35]). The project includes a floating production unit, the drilling of 13 wells, and a 430 km (270 mi) pipeline to transport the gas to the onshore Pluto LNG processing facility near Karratha, which will be expanded.[34][35] Production is expected to begin in 2026.[34] The project has received environmental approval. The Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation has no role in approving such industrial projects, but there is research being undertaken as to whether increased emissions would affect the rock art.[33]

The relationship between traditional owners and Woodside has been complex. In July 2022, Raelene Cooper presented the concerns of some of the traditional owners to the UN in Geneva, which stated "The rock art archives our lore. It is written not on a tablet of stone, but carved into the ngurra, which holds our Dreaming stories and Songlines.". She also wrote to government ministers Linda Burney and Tanya Plibersek.[36]

Pollution and damage

Along with mechanical damage to the rock art from industrial land clearance for roads, pipelines, power lines, and other areas, Murujuga rock art has been damaged by industrial pollution. Acidic dust pollution combines with water to form acids that dissolute manganese and iron compounds, causing the fragmentation of the rock varnish and patina. Researchers suggest reducing emissions is essential to protect the rock art for future generations.[37]

Undersea archaeological site

Summarize

Perspective

On 1 July 2020, scientists published a study reporting on the finding of Australia's first ancient Aboriginal underwater archaeological sites at two locations off the Burrup Peninsula. The 269 artefacts found at Cape Bruguieres, as well as an 8,500-year-old underwater freshwater spring at Flying Foam Passage off Dampier are described in the study.[38] Estimated to be thousands of years old, the artefacts include hundreds of stone tools and grinding stones, evidence of life before sea levels rose between 7,000 and 18,000 years ago, after the last ice age. The Australian Archaeological Association described the research as "highly significant".[39]

The report was the result of four years of work by a team of archaeologists, rock art specialists, geomorphologists, geologists, specialist pilots and scientific divers, funded by the Australian Research Council, in collaboration with the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation,[40] on a project known as the "Deep History of Sea Country" project.[41] Teams from Flinders University, the University of Western Australia, James Cook University, Airborne Research Australia, and the University of York in England were involved.[38]

The site was placed on the WA Aboriginal Heritage List (protected under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972), and the Federal Government said such underwater sites fall under the state jurisdiction. The federal Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018 was updated in 2019 to automatically include sunken aircraft and shipwrecks older than 75 years, but it does not automatically include Aboriginal sites.[38]

Ngajarli Trail

After the Murujuga National Park was closed for some months to allow for its construction, the Ngajarli Trail was completed in August 2020. Traditional owners working in collaboration with the government created a 700-metre (2,300 ft) universal boardwalk, along with interpretative signs. The Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation hopes to improve and enlarge facilities for visitors and to help them appreciate the cultural significance of the site.[42]

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.