Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Metro-land

Suburban area in North-West London, originally built by the Metropolitan Railway From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Metro-land (or Metroland – see note on spelling, below) is a name given to the suburban areas that were built to the north-west of London in the counties of Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire and Middlesex in the early part of the 20th century that were served by the Metropolitan Railway (also known as the Met[a]). The railway company was in the privileged position of being allowed to retain surplus land; from 1919 this was developed for housing by the nominally independent Metropolitan Railway Country Estates Limited (MRCE). The term "Metro-land" was coined by the Met's marketing department in 1915 when the Guide to the Extension Line became the Metro-land guide. It promoted a dream of a modern home in beautiful countryside with a fast railway service to central London until the Met was absorbed into the London Passenger Transport Board in 1933.

Remove ads

Metropolitan Railway

Summarize

Perspective

The Metropolitan Railway was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its mainline heading north from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex suburbs. Its first line connected the mainline railway termini at Paddington, Euston and King's Cross to the City, and when, on 10 January 1863, this line opened with gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives, it was the world's first underground railway.[2][3] When, in 1871 plans were presented for an underground railway in Paris, it was called the Métropolitain in imitation of the line in London.[4] The modern word metro is a short form of the French word. The railway was soon extended from both ends and northwards via a branch from Baker Street. It reached Hammersmith in 1864, Richmond in 1877 and completed the Inner Circle in 1884,[5] but the most important route became the line north into the Middlesex countryside, where it stimulated the development of new suburbs. Harrow was reached in 1880, and the line eventually extended as far as Verney Junction in Buckinghamshire, more than 50 miles (80 kilometres) from Baker Street and the centre of London. From the end of the 19th century, the railway shared tracks with the Great Central Railway route out of Marylebone.[6]

Electric traction was introduced in 1905 with electric multiple units operating services between Uxbridge, Harrow-on-the-Hill and Baker Street. To remove steam and smoke from the tunnels in central London, the Metropolitan Railway purchased electric locomotives, and these were exchanged for steam locomotives on trains at Harrow from 1908.[7] To improve services, more powerful electric and steam locomotives were purchased in the 1920s. A short branch opened from Rickmansworth to Watford in 1925. The 4-mile (6.4 km) long Stanmore branch from Wembley Park was completed in 1932.[8]

Metro-land

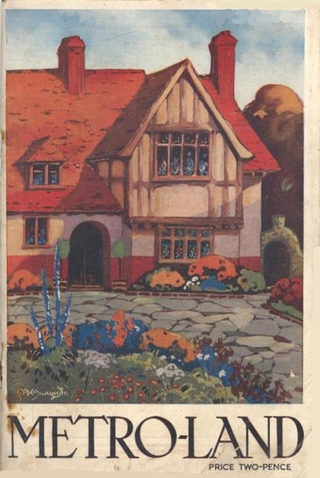

Metro-land was characterised by the construction of Tudor Revival suburban houses (pictured: North Wembley, top, and Kenton, bottom)

Unlike other railway companies, which were required to dispose of surplus land, the Met was in a privileged position with clauses in its acts allowing it to retain land that it believed was necessary for future railway use.[b] Initially the surplus land was managed by the Land Committee, made up of Met directors.[10] In the 1880s, at the same time as the railway was extending beyond Swiss Cottage and building the workers' estate at Neasden,[11] roads and sewers were built at Willesden Park Estate, and the land was sold to builders. Similar developments followed at Cecil Park, near Pinner and, after the failure of the tower at Wembley, plots were sold at Wembley Park.[12][c]

Robert Selbie, then General Manager, thought in 1912 that some professionalism was needed and suggested a company be formed to take over from the Surplus Lands Committee to develop estates near the railway.[15] The First World War delayed these plans however, and it was 1919, with the expectation of a housing boom,[16] before the MRCE was formed. Concerned that Parliament might reconsider the unique position the Met held, the railway company sought legal advice. The legal opinion was that although the Met had authority to hold land, it had none to develop it, so an independent company was created, although all but one of its directors were also directors of the railway company.[17] The MRCE went on to develop estates at Kingsbury Garden Village near Neasden, Wembley Park, Cecil Park and Grange Estate at Pinner and the Cedars Estate at Rickmansworth and create places such as Harrow Garden Village.[16][17]

The term Metro-land was coined by the Met's marketing department in 1915 when the Guide to the Extension Line became the Metro-land guide, priced at 1d. This promoted the land served by the Met for the walker, the visitor and later the house-hunter.[15] Published annually until 1932, the last full year of independence for the Met, the guide extolled the benefits of "The good air of the Chilterns," using language such as "Each lover of Metroland may well have his own favourite wood beech and coppice – all tremulous green loveliness in Spring and russet and gold in October."[18] The dream promoted was of a modern home in beautiful countryside with a fast railway service to central London.[19]

From about 1914 the company had promoted itself as The Met, but after 1920 the commercial manager, John Wardle, ensured that timetables and other publicity material used the term Metro instead.[20][d] Land development also occurred in central London when in 1929 a large, luxurious block of apartments called Chiltern Court opened at Baker Street,[19][e] designed by the Met's architect Charles W. Clark, who was also responsible for the design of a number of station reconstructions in outer "Metro-land" at this time.[24]

A few large houses had been built on parts of Wembley Park, south-west of the Metropolitan station, as early as the 1890s. In 1906, when Watkin’s Tower closed, the Tower Company had become the Wembley Park Estate Company (later Wembley Ltd.), with the aim of developing Wembley as a residential suburb.

Unlike other railways, from an early date the Metropolitan Railway had bought land alongside its line and then developed housing on it. In the 1880s and 1890s it had done so with the Willesden Park Estate near Willesden Green station, and in the early 1900s it developed on land in Pinner, as well as planning the expansion of Wembley Park.

In 1915 by the Metropolitan Railway's publicity department had created the term Metro-land.[25] It was used as the new name for the company's annual guide to the places it served (known as Guide to the Extension Line prior to 1915). The Metro-land guide, although partly written to attract walkers and day trippers, was clearly primarily intended to encourage the building of suburban homes and create middle-class commuters who would use the Metropolitan Railway's trains for all their needs. It was published annually until 1932, but when the Metropolitan became part of London Transport in 1933 the term and guide were abandoned. By then North-West London was well on the road to its reputation for suburbanisation.

The 1924 Metro-land guide describes Wembley Park as "rapidly developed of recent years as a residential district", pointing out that there are several golf courses within a few minutes journey of it.

Over the years during which the guide was published, large numbers of Londoners moved out to the new estates in north-west London. Some of these estates were developed by MRCE, a company that Robert H. Selbie, the Metropolitan Railway's General Manager, set up in 1919. It would eventually build houses along the line, from Neasden reaching far out as Amersham.[26]

One of the earliest of these MRCE developments was a 123-acre one at Chalkhill, within the bounds of what was Repton’s Wembley Park. MRCE acquired the land shortly after it was created and began selling plots in 1921. The railway even put in a siding to bring building materials to the estate.[27]

The term ‘Metroland’ (often seen now without the hyphen - see Note on spelling, below) has become shorthand for the suburban areas that were built in north-west London and in Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire and Middlesex following the Metropolitan branches. It had become immortalised well before the guide stopped being published. A song called "My Little Metro-land Home"[28][29] had been published in 1920, and Evelyn Waugh’s novel Decline and Fall (1928) has a character marrying a Viscount Metroland. She reappears, with the title Lady Metroland, in two more of Waugh's novels; Vile Bodies (1930) and A Handful of Dust (1934).

The British Empire Exhibition further encouraged the new phenomenon of suburban development. Wembley's sewerage was improved, many roads in the area were straightened and widened and new bus services began operating. Visitors were steadily introduced to Wembley and some later moved to the area when houses had been built to accommodate them.[30]

Between 1921 and 1928 season ticket sales at Wembley Park and neighbouring Metropolitan stations rose by over 700%. Like the rest of West London, most of Wembley Park and its environs was fully developed, largely with relatively low-density suburban housing, by 1939.

Absorption of the Met

On 1 July 1933 the Metropolitan Railway amalgamated with other Underground railways, tramway companies and bus operators to form the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB), and the railway became the Metropolitan line of London Transport. The LPTB was not interested in running goods and freight services and the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) took over all freight traffic. At the same time the LNER became responsible for hauling passenger trains with steam locomotives north of Rickmansworth. The lines north of Aylesbury to Verney Junction and Brill were closed; last train to Brill ran on 30 November 1935 and to Quainton Road and Verney Junction on 2 April 1936. Quainton Road continued to be served by the LNER.[31] For a time, the LPTB used the "Metro-land" tag: "Cheap fares to Metro-land and the sea" were advertised in 1934[citation needed] but the "Metro-land" brand was rapidly dropped.[19] London Transport introduced new slogans such as "Away by Metropolitan" and "Good spot, the Chilterns".[citation needed]

Steam traction continued to be used on the outer sections of what had become the "Metropolitan line" until 1961. From that date Metropolitan trains ran only as far as Amersham, with main line services from Marylebone covering stations between Great Missenden and Aylesbury.

Remove ads

Defining Metro-land

The term Metro-land is applied to suburban areas around the route of the Metropolitan Railway, areas which urbanised under the influence of the railway in the 20th century. It applies to land in Middlesex, west Hertfordshire and south Buckinghamshire. The Middlesex area is now administered as the London Boroughs of Brent and Harrow, together with part of the London Borough of Hillingdon.

The architect Hugh Casson regarded Harrow as the "capital city" of Metro-land,[32] while Arthur Mee's King's England described Wembley as its "epitome".[33]

The Metro-land guide insisted that Metro-land was "a country with elastic borders that each visitor can draw for himself". Even so, Metro-land was quite firm that, so far as the Buckinghamshire Chilterns were concerned, its "Grand Duchy" was confined to the hundred of Burnham: "the Chilterns round Marlow and the Wycombes are not in Metro-land".

The usefulness of the term Metro-land, has occasionally led journalists to use the term for the suburban catchment of other underground lines.[34][35]

Remove ads

Slogans and references

Summarize

Perspective

The Metropolitan's terminus at Baker Street was "the gateway to Metro-land" and Chiltern Court, which opened over the station in 1929 and was headquarters during the Second World War of the Special Operations Executive, was "at the gateway to Metro-land". In similar vein, Chorleywood and Chenies, later described by John Betjeman as "the essential Metro-land",[36] were "at the gateway" of the Chiltern Hills (of which Wendover was the "pearl").[37]

Literature and songs

Before the end of the First World War George R. Sims had incorporated the term in verse: "I know a land where the wild flowers grow/Near, near at hand if by train you go,/Metroland, Metroland".

By the 1920s, the word was so ingrained in the consciousness that, in Evelyn Waugh's novel, Decline and Fall (1928), the Hon Margot Beste-Chetwynde took Viscount Metroland as her second husband. Lady Metroland's second appearance in Vile Bodies in 1930 and A Handful of Dust in 1934 further reinforces this.[38]

Metro-land further entered the public psyche with the song "My Little Metro-land Home" (lyrics by Boyle Lawrence and music by Henry Thraile, 1920), while another ditty extolled the virtues of the Poplars estate at Ruislip with the assertion that "It's a very short distance by rail on the Met/And at the gate you'll find waiting, sweet Violet".[32]

Queensbury and its local surroundings and characters were cited in the song "Queensbury Station" by the Berlin-based punk-jazz band The Magoo Brothers on their album "Beyond Believable", released on the Bouncing Corporation label in 1988. The song was written by Paul Bonin and Melanie Hickford, who both grew up and lived in the area.[39]

In 1997, Metroland was the title and setting for a movie starring Christian Bale about the development of the relationship between a husband and wife living in the area. The movie was based on the novel of the same name written by Julian Barnes.

Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark recorded a song Metroland on the English Electric album. It was released as a single, with the video showing the singer dreamily gazing out from a train at an idealised suburban landscape.

"Live in Metro-land"

In 1903 the Metropolitan developed a housing estate at Cecil Park, Pinner, the first of many such enterprises over the next thirty years. Overseen by the Metropolitan's general manager from 1908 to 1930, Robert H Selbie, the railway formed its own Country Estates Company in 1919. The slogan, "Live in Metro-land", was even etched on the door handles of Metropolitan carriages.

Some stations, such as Hillingdon (1923), were built specifically to serve the company's suburban developments. A number, including Wembley Park, Croxley Green (1925) and Stanmore (1932), were designed by Charles W. Clark (who was responsible also for Chiltern Court) in an Arts and crafts "villa" style. These were intended to blend with their surroundings, though, in retrospect, they arguably lacked the panache and vision of Charles Holden's striking, modern designs for the Underground group in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Imitators

Nearly 70 years later the Chilterns Conservation Board was advertising "Chilterns Country – countryside walks from rail stations" (2004). Drawing no doubt on "Metro-land, a guide for ramblers", published by British Railways Southern Region shortly after the Second World War, it referred to the "Rambleland" stations of Surrey and Sussex.[40]

Remove ads

Spirit of Metro-land

Summarize

Perspective

The sentimental and somewhat archaic prose of the Metro-land guide ("the Roman road aslant the eastern border ... the innumerable field-paths which mark the labourer's daily route from hamlet to farm")[41] conjured up a rustic Eden – a Middle England, perhaps[42] – similar to that invoked by Stanley Baldwin (Prime Minister three times between 1923 and 1937) who, though of manufacturing stock, famously donned the mantle of countryman ("the tinkle of the hammer on the anvil in the country smithy, the sound of the scythe against the whetstone").[43] As one historian of the London Underground put it wryly, "the world of Metroland is not cluttered with people: its suburban streets are empty ... There are, it seems, more farm animals than people."[44]

A more cynical view, that sought to contrast illusion with changing times, was offered in 1934 by the composer and conductor Constant Lambert who "conjure[d] up the hideous faux bonhomie of the hiker, noisily wading his way through the petrol pumps of Metroland, singing obsolete sea chanties [sic] with the aid of the Week-End Book, imbibing chemically flavoured synthetic beer under the impression that he is tossing off a tankard of 'jolly good ale and old' ... and astonishing the local garage proprietor by slapping him on the back and offering him a pint of 'four 'alf'".[45] [f]

Town v. country

With similar ambiguity, Metro-land combined idyllic photographs of rural tranquillity with advertising spreads for new, though leafy, housing developments. Herein lay the contradictions well captured by Leslie Thomas in his novel, The Tropic of Ruislip (1974): "in the country but not of it. The fields seemed touchable and yet remote". Writer and historian A. N. Wilson reflected how suburban developments of the early 20th century that had been brought within easy reach of London by the railways, "merely ended up creating an endless ribbon ... not perhaps either town or country".[46] In the process, despite Metro-land's promotion of rusticity, a number of outlying towns and villages were "swallowed up and lost their identity".[47]

Influence of Country Life

Wilson noted that the magazine Country Life, which had been founded by Edward Hudson as Country Life Illustrated in 1897, had influenced this pattern with its advertisements for country houses: "If you were a stockbroker or a lawyer's wife ... you could perhaps afford a new Tudorbethan mansion, with an oak staircase and mullioned windows and half-timbered gables, in Godalming or Esher, or Amersham or Penn".[46] Of the surrounding landscape, Country Life itself has observed that, in its early days, it offered

a rose-tinted view of the English countryside ... idyllic villages, vernacular buildings and already dying rural crafts. All were illustrated with hauntingly beautiful photographs. They portrayed a utopian never-never world of peace and plenty in a pre-industrial Britain.[48]

Growth of Metro-land

By the 1930s the availability of mortgages with an average rate of interest of 41⁄4 per cent meant that private housing was well within the range of most middle class and many working-class pockets.[49] This was a potent factor in the growth of Metro-land: for example, in the first three decades of the 20th century the population of Harrow Weald rose from 1,500 to 11,000 and that of Pinner from 3,000 to 23,000.[50] In 1932 Northwick Park was said to have grown over the previous five years at the rate of 1,000 houses annually and Rayners Lane to "repay a visit at short intervals to see it grow".[41]

Sir John Betjeman

In the mid-20th century the spirit of Metro-land was evoked in three "late chrysanthemums"[51] by Sir John Betjeman (1906–1984), Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death: "Harrow-on-the-Hill" ("When melancholy autumn comes to Wembley / And electric trains are lighted after tea"), "Middlesex" ("Gaily into Ruislip Gardens / Runs the red electric train") and "The Metropolitan Railway" ("Early Electric! With what radiant hope / Men formed this many-branched electrolier"). In his autobiographical Summoned by Bells (1960) Betjeman recalled that "Metroland / Beckoned us out to lanes in beechy Bucks".

Described much later by The Times as the "hymnologist of Metroland",[52] Betjeman reached a wider audience with his celebrated documentary for BBC Television, Metro-land, directed by Edward Mirzoeff, which was first broadcast on 26 February 1973 and was released as a DVD 33 years later. The critic Clive James, who judged the programme "an instant classic", observed that "it saw how the district had been destroyed by its own success".[53]

To mark the centenary of Betjeman's birth his daughter Candida Lycett Green (born 1942) spearheaded a series of celebratory railway events, including an excursion on 2 September 2006 from Marylebone to Quainton Road, now home of the Buckinghamshire Railway Centre.[54] Lycett Green noted of the planning of this trip that among the fine details considered were which filling to have in the baguettes on the train through Metro-land and how long it would stop on the track so that the poem "Middlesex" could be read over the tannoy.[55] The event was in the tradition of earlier commemorations of "Metro-land", such as a centenary parade of rolling stock at Neasden in 1963 and celebrations in 2004 to mark the centenary of the Uxbridge branch.

Avengerland

Metro-land (notably west Hertfordshire) formed the backdrop for the 1960s ABC TV series The Avengers, whose popular imagery was deployed with a twist of fantasy. The archetypal Metro-land subjects (such as the railway station and the quiet suburb) became the settings for fiendish plots and treachery in this series and others, such as The Saint, The Baron and Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased), all of which made regular use of locations within easy reach of film studios at Borehamwood and Pinewood.[56]

Remove ads

Escaping Metro-land

Summarize

Perspective

Some abhorred Metro-land for its predictability and sameness. A. N. Wilson observed that, although semi-detached dwellings of the kind built in the inner Metro-land suburbs in the 1930s "aped larger houses, the stockbroker Tudorbethan of Edwardian Surrey and Middlesex", they were in fact "pokey". He reflected that

as [the husband] went off to the nearest station every morning ... the wife, half liberated and half slave, stayed behind wondering how many of the newly invented domestic appliances they could afford to purchase, and how long the man would hold on to his job in the Slump. No wonder, when war came, that so many of these suburban prisoners felt a sense of release.[46]

Post-war attitudes

By the end of the Second World War architects in general were turning their backs on suburbia; the very word tended to be used pejoratively, even contemptuously. In 1951 Michael Young, one of the architects of the Labour Party's electoral victory in 1945, observed that "one suburb is much like another in an atomised society. Rarely does community flourish", while the American Lewis Mumford, wrote in the New Yorker in 1953 that "monotony and suburbanism" were the result of the "unimaginative" design of Britain's post-war New Towns.[57] When the editor of the Architectural Review, J. M. Richards, wrote in The Castles on the Ground (1946) that "for all the alleged deficiencies of suburban taste ... it holds for ninety out of a hundred Englishmen an appeal which cannot be explained away as some strange instance of mass aberration", he was, in his own words, "scorned by my contemporaries as either an irrelevant eccentricity or a betrayal of the forward looking views of the Modern Movement".[58]

John Betjeman admired John Piper's illustrations for Castles on the Ground, describing the "fake half-timber, the leaded lights and bow windows of the Englishman's castle" as "the beauty of the despised, patronised suburb".[59] However, as the historian David Kynaston observed sixty years later, "the time was far from ripe for Metroland nostalgia".[60]

Julian Barnes: Metroland

Valerie Grove, who conceded that Metro-land was "a kinder word than 'suburbia'" and referred to the less spoilt areas beyond Rickmansworth as "Outer Metro-land", maintained that "suburbia had no visible history. Anyone with any spirit ... had to get out of Metro-land to make their mark".[61]

Thus, the central character of Metroland (1980), a novel by Julian Barnes (born 1946) that was filmed in 1997, ended up in Paris during the disturbances of May 1968 – though, by the late 1970s, having thrown off the yearnings of his youth, he was back in Metro-land. Metroland recounted the essence of suburbia in the early 1960s and the features of daily travel by a schoolboy, Christopher Lloyd, on the Metropolitan line to and from London. During a French lesson, Christopher declared, "J'habite Metroland" ["I live in Metroland"], because it "sounds better than Eastwick [the fictional location of his home], stranger than Middlesex".

In real life, some schoolboys had made similar journeys for more hedonistic reasons. Betjeman recalled that, between the wars, boys from Harrow School had used the Metropolitan for illicit excursions to night clubs in London: "Whenever the police raided the Hypocrites' Club or the Coconut Club, the '43 or the Blue Lantern there would always be Harrovians there".[62]

Social mobility: Tropic of Ruislip

Between Metro-land's heyday before the Second World War and the end of the 20th century, the proportion of owner-occupied dwellings in England, already rising fast from the mid-1920s, doubled from a third to two-thirds.[63] In Tropic of Ruislip, Leslie Thomas's humorous account of suburban sexual and social mores in the mid-1970s (adapted for television as Tropic, ATV 1979), the steady flow of families from council housing on one side of the railway to an executive estate on the other side served to illustrate what was becoming known as "upward mobility".[g] Another sign was that, by the end of the book, "half the neighbourhood" of Plummers Park (probably based on Carpenders Park, on the outskirts of Watford[h]) had moved south of the River Thames to Wimbledon or nearby Southfields. This was put down to the "attractions of Victoriana", which, like suburbia itself, championed at the time by Betjeman's Metro-land, was coming back into fashion; however, it appeared to have just as much to do with couples following each other round in order to maintain extramarital affairs.[citation needed]

Another glimpse of Metro-land in the 1970s was provided by The Good Life, the BBC TV comedy series (1975-78) about suburban self sufficiency. Though set in Surbiton, the programme's location filming was carried out in Northwood, an area reached by the Metropolitan in 1885. A less benign view of Metro-land was offered in the mid-2000s by the detective series Murder in Suburbia (ITV 2004-06), which, though set in the fictional town of Middleford, was also filmed in Northwood and other parts of north west London.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Note on spelling

The form "Metroland" is now in common use, but the 'brand' was hyphenated as "Metro-land" or "METRO-LAND", as that was the form always employed by the Metropolitan Railway in its brochures and on the trains themselves.[65] Evelyn Waugh, John Betjeman (in "Summoned by Bells") and Julian Barnes all dispensed with the hyphen, though Betjeman's documentary of 1973 was titled Metro-land.

See also

Notes and references

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads