Marl

Lime-rich mud or mudstone which contains variable amounts of clays and silt From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, clays, and silt. When hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

Marl makes up the lower part of the cliffs of Dover, and the Channel Tunnel follows these marl layers between France and the United Kingdom. Marl is also a common sediment in post-glacial lakes, such as the marl ponds of the northeastern United States.

Marl has been used as a soil conditioner and neutralizing agent for acid soil and in the manufacture of cement.

Description

Summarize

Perspective

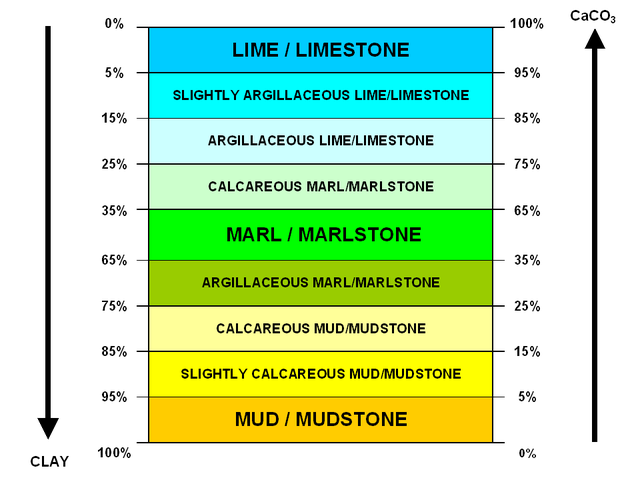

Marl or marlstone is a carbonate-rich mud or mudstone which contains variable amounts of clays and silt. The term was originally loosely applied to a variety of materials, most of which occur as loose, earthy deposits consisting chiefly of an intimate mixture of clay and calcium carbonate,[1] formed under freshwater conditions. These typically contain 35–65% clay and 65–35% carbonate.[2][3] The term is today often used to describe indurated marine deposits and lacustrine (lake) sediments which more accurately should be named 'marlstone'.[4]

Marlstone is an indurated (resists crumbling or powdering) rock of about the same composition as marl. This is more correctly described as an earthy or impure argillaceous limestone. It has a blocky subconchoidal fracture, and is less fissile than shale.[4] The dominant carbonate mineral in most marls is calcite, but other carbonate minerals such as aragonite or dolomite may be present.[5]

Glauconitic marl is marl containing pellets of glauconite, a clay mineral that gives the marl a green color.[6] Glauconite is characteristic of sediments deposited in marine conditions.[7]

Occurrences

Summarize

Perspective

The lower stratigraphic units of the chalk cliffs of Dover consist of a sequence of glauconitic marls followed by rhythmically banded limestone and marl layers.[8] Such alternating cycles of chalk and marl are common in Cretaceous beds of northwestern Europe.[9] The Channel Tunnel follows these marl layers between France and the United Kingdom.[10] Upper Cretaceous cyclic sequences in Germany and marl–opal-rich Tortonian-Messinian strata in the Sorbas Basin related to multiple sea drawdown have been correlated with Milankovitch orbital forcing.[11]

Marl as lacustrine sediment is common in post-glacial lake-bed sediments.[12][13][14] Chara, a macroalga also known as stonewort, thrives in shallow lakes with high pH and alkalinity, where its stems and fruiting bodies become calcified. After the alga dies, the calcified stems and fruiting bodies break down into fine carbonate particles that mingle with silt and clay to produce marl.[15] Marl ponds of the northeastern United States are often kettle ponds in areas of limestone bedrock that become poor in nutrients (oligotrophic) due to precipitation of essential phosphate. Normal pond life is unable to survive, and skeletons of freshwater molluscs such as Sphaerium and Planorbis accumulate as part of the bottom marl.[13]

In Hungary, Buda Marl is found that was formed in the Upper Eocene era. It lies between layers of rock and soil and may be defined it as both "weak rock and strong soil."[16]

Marl is the dominant rock type in the Vaca Muerta Formation in Argentina.

Economic geology

Summarize

Perspective

Marl has been used as a soil conditioner and neutralizing agent for acid soil[13][17] and in the manufacture of Portland cement.[18] Because some marls have a very low permeability, they have been exploited for construction of the Channel Tunnel between England and France and are being investigated for the storage of nuclear waste.

Historical use in agriculture

Marl is one of the oldest soil amendments used in agriculture. In addition to increasing available calcium, marl is valuable for improving soil structure and decreasing soil acidity[19] and thereby making other nutrients more available.[20] It was used sporadically in Britain beginning in prehistoric times[21] and its use was mentioned by Pliny the Elder in the 1st century.[22] Its more widespread use from the 16th century on contributed to the early modern agricultural revolution.[21] However, the lack of a high-energy economy hindered its large-scale use until the Industrial Revolution.[20]

Marl was used extensively in Britain, particularly in Lancashire, during the 18th century. The marl was normally extracted close to its point of use, so that almost every field had a marl pit, but some marl was transported greater distances by railroad. However, marl was gradually replaced by lime and imported mineral fertilizers early in the 19th century.[23] A similar historical pattern was seen in Scotland.[21]

Marl was one of a few soil amendments available in limited quantities in the southern United States, where soils were generally poor in nutrients, prior to about 1840.[24] By the late 19th century, marl was being mined on an industrial scale in New Jersey[25] and was increasingly being used on a more scientific basis, with marl being classified by grade[26][27] and the state geological survey publishing detailed chemical analyses.[28]

Modern agricultural and aquacultural uses

Marl continues to be used for agriculture into the 21st century, though less frequently.[29] The rate of application must be adjusted for the reduced content of calcium carbonate versus straight lime, expressed as the calcium carbonate equivalent. Because the carbonate in marl is predominantly calcium carbonate, magnesium deficiency may be seen in crops treated with marl if they are not also supplemented with magnesium.[17]

Marl has been used in Pamlico Sound to provide a suitable artificial substrate for oysters in a reef-like environment.[29]

Portland cement

Marl has been used in the manufacture of Portland cement.[18] It is abundant and yields better physical and mechanical properties than metakaolin as a supplementary cementitious material[30] and can be calcined at a considerably lower temperature.[31][32]

Civil engineering

The Channel Tunnel was constructed in the West Melbury Marly Chalk, a geological formation containing marl beds. This formation was chosen because of its very low permeability, absence of chert, and lack of fissures found in overlying formations. The underlying Glauconitic Marl is easily recognizable in core samples and helped establish the right level for excavating the tunnel.[33]

Marl soil has poor engineering properties, particularly when alternately wetted and dried.[34] The soils can be stabilized by adding pozzolan (volcanic ash) to the soil.[35]

Nuclear waste storage

Some marl beds have a very low permeability and are under consideration for use in the storage of nuclear waste. One such proposed storage site is the Wellenberg in central Switzerland.[36]

Marl lakes

A marl lake is a lake whose bottom sediments include large deposits of marl.[18] They are most often found in areas of recent glaciation[37] and are characterized by alkaline water, rich in dissolved calcium carbonate, from which carbonate minerals are deposited.[38]

Marl lakes have frequently been dredged or mined for marl, often used for manufacturing Portland cement.[18] However, they are regarded as ecologically important,[39] and are vulnerable to damage by silting, nutrient pollution, drainage, and invasive species. In Britain, only the marl lakes of the more remote parts of northern Scotland are likely to remain pristine into the near future.[38]

See also

- Agricultural lime – Soil additive containing calcium carbonate and other ingredients

- Keuper marl

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.