Aurel Stein

Hungarian-British archaeologist From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sir Marc Aurel Stein, KCIE, FRAS, FBA[1] (Hungarian: Stein Márk Aurél; 26 November 1862 – 26 October 1943) was a Hungarian-born British archaeologist, primarily known for his explorations and archaeological discoveries in Central Asia. He was also a professor at Indian universities.

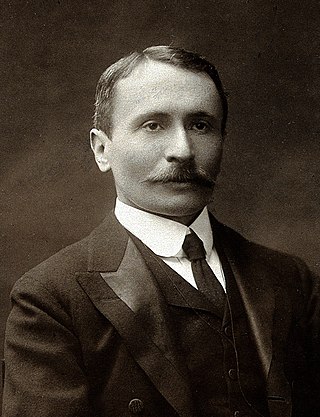

Aurel Stein | |

|---|---|

Stein in 1909 | |

| Born | Stein Márk Aurél 26 November 1862 |

| Died | 26 October 1943 (aged 80) |

| Citizenship | Hungarian (birth) / British (naturalised) from 1904 |

| Alma mater | University of Tübingen |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Archaeology |

Stein was also an ethnographer, geographer, linguist and surveyor. His collection of books and manuscripts bought from Dunhuang caves is important for the study of the history of Central Asia and the art and literature of Buddhism. He wrote several volumes on his expeditions and discoveries which include Ancient Khotan, Serindia and Innermost Asia.

Early life

Stein was born to Náthán Stein and Anna Hirschler, a Jewish couple residing in Budapest in the Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire. His parents and his sister retained their Jewish faith but Stein and his brother, Ernst Eduard, were baptised as Lutherans. At home the family spoke German and Hungarian,[2] Stein graduated from a secondary school in Budapest before going on for advanced study at Universities of Vienna, Leipzig and Tübingen. He graduated in Sanskrit and Persian and received his PhD from Tübingen in 1883.[3]

In 1884, he went to England to study oriental languages and archaeology. In 1886, Stein met the Indologist and philologist Rudolf Hoernlé in Vienna at a conference of Orientalists, learning about an ancient mathematical manuscript discovered in Bakhshali (Peshawar).[4] In 1887 Stein went to India, where he joined the University of the Punjab as Registrar. Later, between 1888 and 1899, he was the Principal of Oriental College, Lahore.[5] During this time, under his supervision Raghunath Temple Sanskrit Manuscript Library at Jammu was established which treasures 5000 rare manuscripts.[6]

Expeditions

Summarize

Perspective

Genesis

Stein was influenced by Sven Hedin's 1898 work Through Asia. In June 1898, he sought the help of Hoernle and a collaboration to find and study Central Asian antiquities. Hoernle was enthusiastic as he had already deciphered the Bower Manuscript and Weber Manuscript by then, found these to be respectively the oldest known birch bark and paper manuscripts of ancient India at the time, had received more artefacts and manuscripts but was concerned about the circumstances of their discovery and their authenticity. He recommended that Stein prepare an expedition proposal and submit it to the Governments of Punjab and India.[4] Stein sent a draft proposal to Hoernle within a month. Hoernle discussed it with Lt Governor of Punjab (British India), who expressed enthusiasm. Stein then submitted a full proposal to explore, map and study the antiquities of Central Asia as per the recommendations of Hoernle, who personally petitioned both the Government of Punjab and Government of India, lobbying for a quick approval. Within weeks, Stein's proposal was informally approved. In January 1899, Stein received the formal approval and funds for his first expedition.[4] Stein thereafter received approval and support for additional expeditions to Chinese Turkestan, other parts of Tibet and Central Asia where the Russians and Germans were already taking interest. He made his famous expeditions with the financial support of Punjab government and the British India government.[4]

The four expeditions

Stein made four major expeditions to Central Asia—in 1900–1901, 1906–1908, 1913–1916 and 1930.[7] He brought to light the hidden treasure of a great civilization which by then was practically lost to the world. One of his significant finds during his first journey during 1900–1901 was the Taklamakan Desert oasis of Dandan Oilik where he was able to uncover a number of relics. During his third expedition in 1913–1916, he excavated at Khara-Khoto.[8] Later he explored in the Pamirs, seeking the site of the now-lost Stone Tower which the 2nd century polymath Claudius Ptolemy had noted as the half-way mark of the Silk Road in his famous treatise Geography.[9]

The British Library's Stein collection of Chinese, Tibetan and Tangut manuscripts, Prakrit wooden tablets, and documents in Khotanese, Uyghur, Sogdian and Eastern Turkic is the result of his travels through central Asia during the 1920s and 1930s. Stein discovered manuscripts in the previously lost Tocharian languages of the Tarim Basin at Miran and other oasis towns, and recorded numerous archaeological sites, especially in Iran and Balochistan.

When Stein visited Khotan he was able to render in Persian a portion of the Shahnama after he came across a local reading the Shahnama in Turki.[10]

During 1901, Stein was responsible for exposing forgeries of Islam Akhun, as well as establishing the details and the authenticity of manuscripts that had been discovered before 1896 in northwest China.[4]

Stein's greatest discovery was made at the Mogao Caves, also known as "Caves of the Thousand Buddhas", near Dunhuang in 1907. It was there that he discovered a printed copy of the Diamond Sutra which is the world's oldest printed text, dating to AD 868, along with 40,000 other scrolls (all removed by gradually winning the confidence and bribing the Taoist caretaker).[11] He took 24 cases of manuscripts and 4 cases of paintings, decorated textiles (such as the Miraculous Image of Liangzhou) and relics. He was knighted for his efforts, but Chinese nationalists dubbed him a burglar and staged protests against him, although most others have seen his actions as at least advancing scholarship.[12][13] His discovery inspired other French, Russian, Japanese, and Chinese treasure hunters and explorers who also took their toll on the collection.[14] Aurel Stein discovered 5 letters written in Sogdian known as the "Ancient Letters" in an abandoned watchtower near Dunhuang in 1907, dating to the end of the Western Jin dynasty.[15]

During his expedition of 1906–1908 while surveying south of the Johnson Line in the Kunlun Mountains, Stein suffered frostbite and lost several toes on his right foot.

When he was resting from his extended journeys into Central Asia, he spent most of his time living in a tent in the alpine meadow called Mohand Marg which lies at the mouth atop the Sind Valley. Years earlier, working from this idyllic spot he translated Rajatarangini from Sanskrit into English, which had then been published in 1900.[16][17] A memorial stone was erected in Mohand Marg on 14 September 2017 where Stein used to pitch his tent.[18]

The fourth expedition to Central Asia, however, ended in failure. Stein did not publish any account, but others have written of the frustrations and rivalries between British and American interests in China, between Harvard's Fogg Museum and the British Museum, and finally, between Paul J. Sachs and Langdon Warner, the two Harvard sponsors of the expedition.[19]

Between 1940 and 1943, Aurel Stein undertook 2 expeditions to along the Ghaggar-Hakra River to find physical evidence of the Saraswati River described in the Rig Veda. While he didn't definitively establish the region's chronological archaeological sequence, his work significantly advanced Indian archaeology. Surveying from Hanumangarh to Bahawalpur, he identified approximately 100 prehistoric and historical sites, conducting exploratory excavations at some. His observations on the geographical spread of these sites proved valuable to later researchers, including Amalananda Ghosh (3 March 1910 – 1981) and Katy Dalal. Notably, he documented sites such as Munda, Bhadrakali Temple, and Derwar.[20]

Personal life

Stein was a lifelong bachelor, but was always accompanied by a dog named "Dash" (of which there were seven).[21][22] He became a British citizen in 1904.[23] He died in Kabul on 26 October 1943 and is buried there in the Sherpur Cantonment.[24]

Great Game

Stein, as well as his rivals Sven Hedin, Sir Francis Younghusband and Nikolai Przhevalsky, were active players in the British-Russian struggle for influence in Central Asia, the so-called Great Game. Their explorations were supported by the British and Russian Empires as they filled in the remaining "blank spots" on the maps, providing valuable information and creating "spheres of influence" for archaeological exploration as they did for political influence.[25]

The art objects he collected are divided between the British Museum, the British Library, the Srinagar Museum, and the National Museum, New Delhi.

Honours

Summarize

Perspective

Stein received a number of honours during his career. In 1909, he was awarded the Founder's Medal by the Royal Geographical Society 'for his extensive explorations in Central Asia, and in particular his archaeological work'.[26] In 1909, he was awarded the first Campbell Memorial Gold Medal by the Royal Asiatic Society of Bombay. He was awarded a number of other gold medals: the Gold Medal of the Société de Géographie in 1923; the Grande Médaille d'or of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland in 1932; and the Gold Medal of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1935. In 1934, he was awarded the Huxley Memorial Medal of Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.[27]

In the 1910 King's Birthday Honours, he was appointed Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE) for his service as Inspector-General of Education and Archaeological Surveyor in the North-West Frontier Province.[28] Two years later, in the 1912 Birthday Honours, he was promoted to Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (KCIE) for his service as Superintendent of the Archaeological Department, North-West Frontier Circle.[29]

He was made an honorary Doctor of Letters (DLitt) by the University of Oxford in 1909. He was made an honorary Doctor of Science (DSc) by the University of Cambridge in 1910.[27] He was made an honorary Doctor of Laws (LLD) by the University of St Andrews in 1939.[27][30]

In 1919, Stein became a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[31] In 1921, he was elected Fellow of the British Academy (FBA).[5] He was elected an International Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1930 and an International Member of the American Philosophical Society in 1939.[32]

Publications

Summarize

Perspective

- 1896. "Notes on the Ancient Topography of the Pīr Pantsāl Route." Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. LXIV, Part I, No. 4, 1895. Calcutta 1896.

- 1896. Notes on Ou-k'ong's account of Kaçmir. Wien: Gerold, 1896. Published in both English and German in Vienna.

- 1898. Detailed Report on an Archaeological Tour with the Buner Field Force, Lahore, Punjab Government Press.

- 1900. Kalhaṇa's Rājataraṅgiṇī – A Chronicle of the Kings of Kaśmīr, 2 vols. London, A. Constable & Co. Ltd. Reprint, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 1979.

- 1904 Sand-Buried Ruins of Khotan, London, Hurst and Blackett, Ltd. Archived 4 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine Reprint Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Madras, 2000 Sand-Buried Ruins of Khotan: vol.1 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- 1905. Report of Archaeological Survey Work in the North-West Frontier Province and Baluchistan, Peshawar, Government Press, N.W. Frontier Province.

- 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols. Clarendon Press. Oxford. Archived 5 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine[33] Ancient Khotan: vol.1 Archived 21 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine Ancient Khotan: vol.2 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- 1912. Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal Narrative of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China, 2 vols. London, Macmillan & Co. Reprint: Delhi. Low Price Publications. 1990. Ruins of Desert Cathay: vol.1 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Ruins of Desert Cathay: vol.2 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- 1918. "Routes from the Panjab to Turkestan and China Recorded by William Finch (1611)." The Geographical Journal, Vol. 51, No. 3 (Mar., 1918), pp. 172–175.

- 1921a. Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 5 vols. London & Oxford, Clarendon Press. Reprint: Delhi. Motilal Banarsidass. 1980.[33] Serindia: vol.1 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Serindia: vol.2 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Serindia: vol.3 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Serindia: vol.4 Archived 2 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Serindia: vol.5 Archived 28 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- 1921b. The Thousand Buddhas: ancient Buddhist paintings from the cave-temples of Tung-huang on the western frontier of China.[33] The Thousand Buddhas: vol.1 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- 1921c. "A Chinese expedition across the Pamirs and Hindukush, A.D. 747". Indian Antiquary 1923.[34]

- 1923 Memoir On Maps Of Chinese Turkistan

- 1923 Memoir on Maps of Chinese Turkistan and Kansu: vol.1 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- 1925 Innermost Asia: its geography as a factor in history. London: Royal Geographical Society. Geographical Journal, Vol. 65, nos. 5–6 (May- June 1925)

- 1927 Alexander's Campaign On The Indian North-west Frontier. The Geographic Journal, (Nov/Dec 1927)

- 1928. Innermost Asia: Detailed Report of Explorations in Central Asia, Kan-su and Eastern Iran, 5 vols. Oxford, Clarendon Press. Reprint: New Delhi. Cosmo Publications. 1981.[33] Innermost Asia: vol.1 Archived 24 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine Innermost Asia: vol.2 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Innermost Asia: vol.3 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Innermost Asia: vol.4 Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- 1929. On Alexander's Track to the Indus: Personal Narrative of Explorations on the North-West Frontier of India. London, Macmillan & Co. Reprint: New York, Benjamin Blom, 1972.

- 1932 On Ancient Central Asian Tracks: Brief Narrative of Three Expeditions in Innermost Asia and Northwestern China. Reprinted with Introduction by Jeannette Mirsky. Book Faith India, Delhi. 1999.

- 1933 On Ancient Central-Asian Tracks: vol.1 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- 1937 Archaeological Reconnaissances in North-Western India and South-Eastern Īrān: vol.1 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- 1940 Old Routes of Western Iran: Narrative of an Archaeological Journey Carried out and Recorded, MacMillan and co., limited. St. Martin's Street, London.

- 1944. "Archaeological Notes from the Hindukush Region". J.R.A.S., pp. 1–24 + fold-out.

A more detailed list of Stein's publications is available in Handbook to the Stein Collections in the UK,[8] pp. 49–61.

See also

Footnotes

References and further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.