Mahāvākyas

Aspect of the Upanishads From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

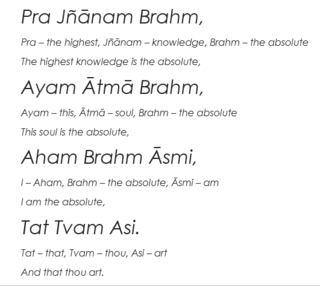

The Mahāvākyas (sing.: mahāvākyam, महावाक्यम्; plural: mahāvākyāni, महावाक्यानि) are "The Great Sayings" of the Upanishads, with mahā meaning great and vākya, a sentence. The Mahāvākyas are traditionally considered to be four in number,[1][2] though actually five are prominent in the post-Vedic literature:[3]

- Tat Tvam Asi (तत् त्वम् असि) - traditionally interpreted as "That Thou Art" (that you are),[4][5][6] (Chandogya Upanishad 6.8.7 of the Sama Veda, with tat in Ch.U.6.8.7 referring to sat, "the Existent"[7][8][9]); correctly translated as "That's how [thus] you are,"[4][6][10][11] with tat in Ch.U.6.12.3 referring to "the very nature of all existence as permeated by [the finest essence]"[12][13]

- Ahaṁ Brahmāsmi (अहं ब्रह्मास्मि) - "I am Brahman", or "I am Divine"[14] (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 1.4.10 of the Yajur Veda)

- Prajñānaṁ Brahma (प्रज्ञानं ब्रह्म) - "Prajñāna[note 1] is Brahman"[note 2], or "Brahman is Prajñāna"[web 2] (Aitareya Upanishad 3.3 of the Rig Veda)

- Ayam Ātmā Brahma (अयम् आत्मा ब्रह्म) - "This Self (Atman) is Brahman" (Mandukya Upanishad 1.2 of the Atharva Veda)

- Sarvaṃ Khalvidaṃ Brahma - "All this indeed is Brahman"[3]

Those statements are instrumental in the Advaita Vedanta as valid scriptural statements which reveal that the individual self (jīvá), which appears as a separate existence, is in essence (ātmán) part and manifestation of the whole (Brahman). They are less prominent in other Vedanta-traditions, which emphasize the supremacy of Vishnu, and give a different interpretation of these statements.

The four principal Mahavakyas

Though there are many Mahavakyas, four of them, one from each of the four Vedas, are often mentioned as "the Mahavakyas".[17] Other Mahavakyas are:

- ekam evadvitiyam brahma - Brahman is one, without a second (Chāndogya Upaniṣad)

- so 'ham - I am that (Isha Upanishad)

- sarvam khalv idam brahma - All of this is brahman (Chāndogya Upaniṣad 3.14.1)

- etad vai tat - This, verily, is That (Katha Upanishad)

People who are initiated into sannyasa in Advaita Vedanta are being taught the four [principal] mahavakyas as four mantras, "to attain this highest of states in which the individual self dissolves inseparably in Brahman".[18] According to the Advaita Vedanta tradition, the four Upanishadic statements indicate the real identity of the individual (jivatman) as sat (the Existent), Brahman, consciousness. According to the Vedanta-tradition, the subject matter and the essence of all Upanishads are the same, and all the Upanishadic Mahavakyas express this one universal message in the form of terse and concise statements.[citation needed] In later Sanskrit usage, the term mahāvākya came to mean "discourse", and specifically, discourse on a philosophically lofty topic.[web 3]

Tat Tvam Asi

Summarize

Perspective

Chandogya Upanishad 6.8.7,[19] in the dialogue between Uddalaka and his son Śvetaketu. It appears at the end of a section, and is repeated at the end of the subsequent sections as a refrain:

[6.2.1] In the beginning, son, this world was simply what is existent - one only, without a second. [6.2.3] And it thought to itself: "let me become many. Let me propagate myself." [6.8.3] It cannot be without a root [6.8.4] [l]ook to the existent as the root. The existent, my son, is the root of all these creatures - the existent is their resting place, the existent is their foundation[7] The finest essence here—that constitutes the self of this whole world; that is the truth; that is the self (ātman). And that's how you are, Śvetaketu.[10]

In ChU.6.8.12 it appears as follows:

'Bring a banyan fruit.'

'Here it is, sir.'

'Cut it up.'

'I've cut it up, sir.'

'What do you see here?'

'These quite tiny seeds, sir.'

'Now, take one of them and cut it up.'

'I've cut it up, sir.'

'What do you see there?'

'Nothing, sir.'

Then he told him: 'This finest essence here, son, that you can't even see—look how on account of that finest essence this huge banyan tree stands here.'Believe, my son: the finest essence here—that constitutes the self of this whole world; that is the truth; that is the self (ātman). And that's how you are, Śvetaketu.'[10]

Etymology and translation

Tat Tvam Asi (Devanagari: तत्त्वमसि, Vedic: tát tvam ási) is traditionally translated as "Thou art that", "That thou art", "That art thou", "You are that", "That you are", or "You're it"; although according to Brereton and others the proper translation would be "In that way [=thus] are you, Svetaketu",[20][4] or "that's how you are":[9][6]

- tat - "it", "that"; or alternatively "thus",[20][4] "in that way",[20][4] "that's how".[9][6] From tat an absolutive derivation can be formed with the suffix -tva: tattva,[21] 'thatness', 'principle', 'reality' or 'truth';[22] compare tathātā, "suchness", a similar absolutive derivation from tathā - 'thus', 'so', 'such', only with the suffix -tā, not -tva.

- tvam - you, thou[23][24]

- asi - are, 'art'[24]

In Ch.U.6.8.7 tat refers to Sat, "the Existent",[7][8][25] Existence, Being.[24] Sat, "the Existent", then is the true essence or root or origin of everything that exists,[8][25][24] and the essence, Atman, which the individual at the core is.[26][27] As Shankara states in the Upadesasahasri:

Up.I.174: "Through such sentences as 'Thou art That' one knows one's own Atman, the Witness of all the internal organs." Up.I.18.190: "Through such sentences as "[Thou art] the Existent" [...] right knowledge concerning the inner Atman will become clearer." Up.I.18.193-194: "In the sentence "Thou art That" [...] [t]he word 'That' means inner Atman."[28]

While the Vedanta tradition equates sat ("the Existent") with Brahman, as stated in the Brahma Sutras, the Chandogya Upanishad itself does not refer to Brahman.[8][6][note 3][6]

According to Brereton, followed by Patrick Olivelle[9] and Wendy Doniger, [11][note 4] the traditional translation as "you are that" is incorrect, and should be translated as "In that way [=thus] are you, Svetaketu."[20][4][note 5] That, then, in ChU.6.8.12 refers to "the very nature of all existence as permeated by [the finest essence]",[12][13] and which is also the nature of Svetaketu.[note 6] Lipner expresses reservations on Brereton's interpretation, stating that it is technically plausible, but noting that "Brereton concedes that the philosophical import of the passage may be represented by the translation 'That you are', where tat as 'that' would refer to the supreme Being (sat/satya)."[7]

Interpretation

Major Vedantic schools offer different interpretations of the phrase:

- Advaita - absolute equality of 'tat', the Ultimate Reality, Brahman, and 'tvam', the Self, Atman.

- Shuddhadvaita - oneness in "essence" between 'tat' and individual self; but 'tat' is the whole and self is a part.

- Vishishtadvaita -'tvam' denotes the Jiva-antaryami Brahman while 'tat' refers to Jagat-Karana Brahman.

- Dvaitadvaita - equal non-difference and difference between the individual self as a part of the whole which is 'tat'.

- Dvaita of Madhvacharya - tat tvam asi is read as atat tvam asi, meaning "that (parama) Aatma is the essence of all, you are not Him,"[31] or "Atma (Self), thou art, thou art not God."[a]

- Acintya Bheda Abheda - inconceivable oneness and difference between individual self as a part of the whole which is 'tat'.

Aham Brahma Asmi

Summarize

Perspective

Aham Brahmāsmi (Devanagari: अहम् ब्रह्मास्मि), "I am Brahman" is in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 1.4.10 of the Shukla Yajurveda:

[1.4.1] In the beginning this world was just a single body (ātman) shaped like a man. He looked around and saw nothing but himself. The first thing he said was, 'Here I am!' and from that the name 'I' came into being. [1.4.9] Now, the question is raised; 'Since people think that they will become the Whole by knowing brahman, what did brahman know that enabled it to become the Whole? [1.4.10] In the beginning this world was only brahman, and it knew only itself (ātman), thinking: 'I am brahman.' As a result, it became the Whole [...] If a man knows 'I am brahman' in this way, he becomes the whole world. Not even the gods are able to prevent it, for he becomes their very self (ātman).[33][note 7]

Aham Brahmasmi is the core philosophy in advaita vedanta, indicating absolute oneness of atman with brahman.[34]

Etymology

- Aham (अहम्) - literally "I".

- Brahma (ब्रह्म) - ever-full or whole (ब्रह्म is the first case ending singular of Brahman).

- Asmi (अस्मि) - "am," the first-person singular present tense of the verb as (अस्), "to be".[citation needed]

Ahaṁ Brahmāsmi then means "I am the Absolute" or "My identity is cosmic",[35] but can also be translated as "you are part of god just like any other element".

Explanations

In his comment on this passage, Sankara explains that here Brahman is not the conditioned Brahman (saguna); that a transitory entity cannot be eternal; that knowledge about Brahman, the infinite all-pervading entity, has been enjoined; that knowledge of non-duality alone dispels ignorance; and that the meditation based on resemblance is only an idea. He also tells us that the expression Aham Brahmaasmi is the explanation of the mantra

That ('Brahman') is infinite, and this ('universe') is infinite; the infinite proceeds from the infinite. (Then) taking the infinitude of the infinite ('universe'), it remains as the infinite ('Brahman') alone. - (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad V.i.1)[note 8]

He explains that non-duality and plurality are contradictory only when applied to the Self, which is eternal and without parts, but not to the effects, which have parts.[36] The aham in this memorable expression is not closed in itself as a pure mental abstraction but it is radical openness. Between Brahman and aham-brahma lies the entire temporal universe experienced by the ignorant as a separate entity (duality).[37]

Vidyāranya in his Panchadasi (V.4) explains:

Infinite by nature, the Supreme Self is described here by the word Brahman (lit. ever expanding; the ultimate reality); the word asmi denotes the identity of aham and Brahman. Therefore, (the meaning of the expression is) "I am Brahman".[note 9] Vaishnavas, when they talk about Brahman, usually refer to impersonal Brahman, brahmajyoti (rays of Brahman). 'Brahman' according to them means God—Narayana, Rama or Krishna. Thus, the meaning of aham brahma asmi according to their philosophy is that "I am a drop of Ocean of Consciousness", or "I am Self, part of cosmic spirit, Parabrahma". Here, the term 'Parabrahma' is introduced to avoid confusion. If Brahman can mean Self (though, Parabrahma is also the Self, but Supreme one—Paramatma), then Parabrahma should refer to God, Lord Vishnu.

Prajñānam Brahma

Summarize

Perspective

Aitareya Upanishad 3.3 of the Rigveda, translation Olivelle:

[1] Who is this self (ātman)? - that is how we venerate. [2] Which of these is the self? Is it that by which one sees? Or hears? Smells [etc...] But these are various designations of cognition. [3] It is brahman; it is Indra; it is all the gods. It is [...] earth, wind, space, the waters, and the lights [...] It is everything that has life [...] Knowledge is the eye of all that, and on knowledge it is founded. Knowledge is the eye of the world, and knowledge, the foundation. Brahman is knowing.[38]

Etymology and translation

Several translations, and word-orders of these translations, are possible:

Prajñānam:

- jñāna means "understanding", "knowledge", and sometimes "consciousness"[39]

- Pra is a prefix which could be translated as "higher", "greater", "supreme" or "premium",[40] or "being born or springing up",[41] referring to a spontaneous type of knowing.[41][note 10]

Prajñānam as a whole means:

Related terms are jñāna, prajñā and prajñam, "pure consciousness".[42] Although the common translation of jñānam[42] is "consciousness", the term has a broader meaning of "knowing"; "becoming acquainted with",[web 8] "knowledge about anything",[web 8] "awareness",[web 8] "higher knowledge".[web 8]

Brahman:

Meaning: Most interpretations state: "Prajñānam (noun) is Brahman (adjective)". Some translations give a reverse order, stating "Brahman is Prajñānam",[web 2] specifically "Brahman (noun) is Prajñānam (adjective)": "The Ultimate Reality is wisdom (or consciousness)".[web 2] Sahu explains:

Prajnanam iti Brahman - wisdom is the Self. Prajnanam refers to the intuitive truth which can be verified/tested by reason. It is a higher function of the intellect that ascertains the Sat or Truth/Existent in the Sat-Chit-Ananda or truth/existent-consciousness-bliss, i.e. the Brahman/Atman/Self/person [...] A truly wise person [...] is known as Prajna - who has attained Brahmanhood itself; thus, testifying to the Vedic Maha Vakya (great saying or words of wisdom): Prajnanam iti Brahman.[43]

And according to David Loy,

The knowledge of Brahman [...] is not intuition of Brahman but itself is Brahman.[44]

Ayam Ātmā Brahma

Summarize

Perspective

Ayam Atma Brahma (Sanskrit: अयम् आत्मा ब्रह्म) is a Mahāvākya which is found in the Mandukya Upanishad of the Atharvaveda.[45][46] According to the Guru Gita, "Ayam Atma Brahma" is a statement of practice.[47]

Etymology and meaning

The Sanskrit word ayam means 'it'. Ātman means ‘Atma’ or 'self'. Brahman is the highest being. So "Ayam Atma Brahma" means 'Atma is Brahman'.[47]

Source and Significance

The Mahavakya is found in the Mandukya Upanishad of the Atharva Veda.[45][46] It is mentioned in the Mundaka Upanishad 1-2,

[1] OM - this whole world is that syllable! Here is a further explanation of it. The past, the present and the future - all that is simply OM; and whatever else that is beyond the three times, that also is simply OM - [2] for this brahman is the Whole. Brahman is this self (ātman); that [brahman] is this self (ātman) consisting of four quarters.[48]

In Sanskrit:

सर्वं ह्येतद् ब्रह्मायमात्मा ब्रह्म सोऽयमात्मा चतुष्पात् ॥ २ ॥

sarvaṁ hy etad brahmāyam ātmā brahma so'yam ātmā catuṣpāt

The Mundaka Upanishad, in the first section of the second Mundaka, defines and explains the Atma-Brahma doctrine.

It claims that just as a burning fire produces thousands of sparks and leaps and bounds in its own form, so the living beings originate from Brahman in its own form.[45] Brahman is immortal, except the body, it is both external and internal, ever generated, except the mind, except the breath, yet from it emerges the inner soul of all things.[46]

From Brahman breath, mind, senses, space, air, light, water, earth, everything is born. The section expands on this concept as follows,[45][46]

The sky is his head, his eyes the sun and the moon,

the quarters his ears, his speech the Vedas disclosed,

the wind his breath, his heart the universe,

from his feet came the earth, he is indeed the inner Self of all things.

From him comes fire, the sun being the fuel,

from the soma comes the rain, from the earth the herbs,

the male pours the seed into the female,

thus many beings are begotten from the Purusha.

From him come the Rig verses, the Saman chants, the Yajus formulae, the Diksha rites,

all sacrifices, all ceremonies and all gifts,

the year too, the sacrificers, the worlds,

where the moon shines brightly, as does sun.

From him, too, gods are manifold produced,

the celestials, the men, the cattle, the birds,

the breathing, the rice, the corn, the meditation,

the Shraddha (faith), the Satya (truth), the Brahmacharya, and the Vidhi (law).

The Mundaka Upanishad verse 2.2.2 claims that Atman-Brahman is real.[49] Verse 2.2.3 offers help in the process of meditation, such as Om. Verse 2.2.8 claims that the one who possesses self-knowledge and has become one with Brahman is free, not affected by Karma, free from sorrow and Atma-doubt, he who is happy.[50][51] The section expands on this concept as follows,

That which is flaming, which is subtler than the subtle,

on which the worlds are set, and their inhabitants -

That is the indestructible Brahman.[52]

It is life, it is speech, it is mind. That is the real. It is immortal.

It is a mark to be penetrated. Penetrate It, my friend.

Taking as a bow the great weapon of the Upanishad,

one should put upon it an arrow sharpened by meditation,

Stretching it with a thought directed to the essence of That,

Penetrate[53] that Imperishable as the mark, my friend.

Om is the bow, the arrow is the Self, Brahman the mark,

By the undistracted man is It to be penetrated,

One should come to be in It,

as the arrow becomes one with the mark.

Etymology and translation

- sarvam etad - everything here,[55] the Whole,[48] all this

- hi - certainly

- brahma - Brahman

- ayam - this[web 9]

- ātmā - Atman, self, essence

- brahma - Brahman

- so 'yam ātmā - "this very atman"[55]

- catuṣpāt - "has four aspects"[55]

While translations tend to separate the sentence in separate parts, Olivelle's translation uses various words in adjunct sets of meaning:

- सर्वं ह्येतद् ब्रह्म sarvam hyetad brahma - "this brahman is the Whole"

- ब्रह्मायमात्मा brahma ayam atma - "brahman is ātman"

- ब्रह्म सोऽयमात्मा brahman sah ayam atman - "brahman is this (very) self"

The Mandukya Upanishad repeatedly states that Om is ātman, and also states that turiya is ātman.[56] The Mandukya Upanishad forms the basis of Gaudapada's Advaita Vedanta, in his Mandukya Karika.

Sarvaṃ Khalvidaṃ Brahma

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2025) |

Sarvaṃ Khalvidaṃ Brahma - "All this indeed is Brahman"[3]

See also

Notes

- Deutsch & Dalvi (2004, p. 8): "Although the text does not use the term brahman, the Vedanta tradition is that the Existent (sat) referred to is no other than Brahman."

- Doniger (2010, p. 711): "Joel Brereton and Patrick Olivelle have argued, fairly convincingly, that it should rather be translated, 'And that's how you are.{'}"

- As Brian Black explains: "the pronoun tat (that) is neuter, and therefor cannot correspond with the masculine tvam (you). Thus [...] if "you are that" was the intended meaning, then the passage should read sa tvam asi."[6] Brereton concludes that tat tvam asi is better rendered as "in that way you are".[29][4] According to Brereton, the "That you are" refrain originally belonged to Ch.U.6.12, from where it was duplicated to other verses.[30]

- Brereton (1986, p. 109) "First, the passage establishes that the tree grows and lives because of an invisible essence. Then, in the refrain, it says that everything, the whole world, exists by means of such an essence. This essence is the truth, for it is lasting and real. It is the self, for everything exists by reference to it. Then and finally, Uddalaka personalizes the teaching. Svetaketu should look upon himself in the same way. He, like the tree and the whole world, is pervaded by this essence, which is his final reality and his true self.

- "ब्रह्म वा इदमग्र आसीत्, तदात्मनामेवावेत्, अहम् ब्रह्मास्मीति

- पूर्णमदः पूर्णमिदं पूर्णात्पूर्णमुदच्यते

- स्वतः पूर्णः परात्माऽत्र ब्रह्मशब्देन वर्णितः

- For the Dvaita Vedanta school of Madhva, the term Mahāvākyas is misplaced, as all statements in the Vedas are equally important, declaring the difference between atman and Brahman.[32] According to Pandurangi, based on sandhi rules, स आत्माऽतत्त्वमसि could be split as 'Atat Tvam Asi' (Sanskrit: स आत्मा अतत्त्वम् असि) - meaning "that (parama) Aatma is the essence of all, you are not Him."[31] It can also be translated as "Atma (Self), thou art, thou art not God." In refutation of Mayavada (Mayavada sata dushani), text 6, tat tvam asi is translated as "you are a servant of the Supreme (Vishnu)."

References

Sources

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.