Liverpool Collegiate School

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Liverpool Collegiate School was an all-boys grammar school, later a comprehensive school, in the Everton area of Liverpool.

This article possibly contains original research. (October 2020) |

Foundations

Summarize

Perspective

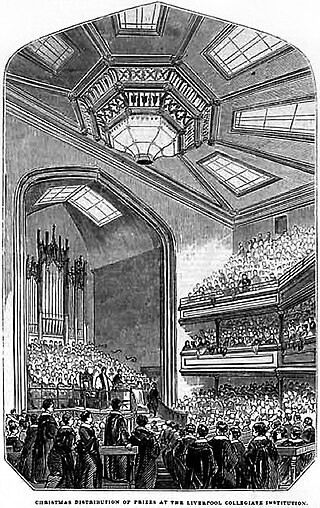

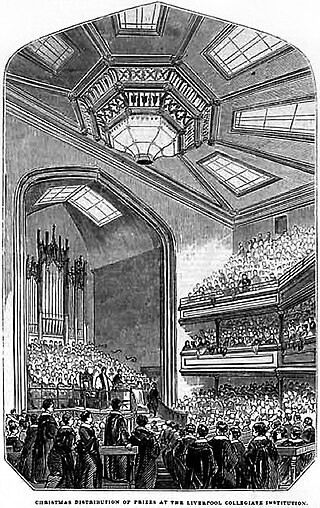

The Collegiate is a striking, Grade II listed building,[1] with a facade of pink Woolton sandstone, designed in Tudor Gothic style by the architect of the city's St. George's Hall, Harvey Lonsdale Elmes. The foundation stone was laid in 1840 and the Liverpool Collegiate Institution was opened by William Gladstone on 6 January 1843, originally as a fee-paying school for boys of middle-class parents and administered as three distinct organisations under a single headmaster. The Upper School became Liverpool College and relocated to Lodge Lane in 1884, whilst the Middle and Lower (or Commercial) Schools occupied the original site and would combine to form the Liverpool Collegiate School in 1908.

The Collegiate magazine, Esmeduna, which first appeared in 1896 and continued publication until 1978, was named after the ancient Liverpool manor mentioned in the Domesday Book, a name which had evolved into 'Smethesdune' by 1288 and survives to this day as Smithdown Road. Although aspects of Collegiate School life such as the annual Prize Giving, Founders Day Service, the school motto in Latin, and Esmeduna, along with the majestic Shaw Street building itself, stem from Victorian times, many enduring traditions originated after the Education Act 1902 gave new local education authorities powers to run secondary schools. The Collegiate was purchased by Liverpool Corporation in 1907 and was transformed into a single, integrated establishment entrusted to provide a high quality grammar school education.

The Grammar School years

Summarize

Perspective

The first headmaster of the new, LEA-controlled Liverpool Collegiate School was Samuel Edward Brown, appointed in 1908, a Cambridge graduate who set out to secure academic success at a time when the mark of a great school was the number of pupils winning university scholarships. The Collegiate also started to earn an enviable reputation within the city and beyond, and pupil numbers rose from around 400 in 1908 to over 1000 by the early 1920s. Fuelled by the desire to prove itself more than a poor relation of Liverpool College, the School succeeded in attracting "first class graduates, many from Oxbridge, to teach at the Collegiate, in a depressingly urban setting in what was then an unfashionable Northern city", inspirational teachers who helped "to transform the school in a generation into one of the leading grammar schools in the country".[2]

Yearly dramatic or musical productions were instigated, including the school tradition of staging Gilbert & Sullivan operettas which endured for half a century. A new school organ was installed by Rushworth and Dreaper in 1913. Annual School Camps began in 1914, and from the 1920s Games lessons were conducted at Holly Lodge playing fields in West Derby.

In 1929, following the death of the first headmaster, the post was taken up by Arnold MacKenzie Gibson. He embarked on a broadening of the school curriculum and wished to place as much emphasis on the 'average boy' as the high-achieving university candidate. Gibson put in place alternative routes by which boys could make progress up the school and tried to ensure that all pupils received a well-rounded education, believing the education of the whole person, for leisure as much as work, to be as important as subject specialisation. From the early 1930s more school trips were arranged including a summer school at Dunkirk, regular exchanges with pupils in France and Germany and the continuation of the customary summer camp on the Isle of Man.

A new school song, 'Paean Esmedunensis', with music by Gibson and words in Latin by his deputy, Victor Dunstan, was first performed at the Annual Prize Giving of 1931 and would last the lifetime of the Collegiate.

| Paean Esmedunensis (abridged) | Esmedunian Hymn (English translation) |

|---|---|

|

Vivat haec sodalitas, |

Long live this fellowship, |

Yearly school plays, school concerts and exhibitions of work continued throughout the 1930s, and the headmaster was able to report rising academic achievement at successive Prize Giving ceremonies. Gibson was also urging the building of a new Collegiate building in West Derby and in 1936 the Liverpool Education Committee recommended to the City Council the purchase of land in Meadow Lane. Proposals were set aside, however, as the international situation became increasingly tense during the late 1930s. School visits to Belgium and, perhaps surprisingly, to Germany continued.

In July 1939, with war being anticipated, the Collegiate sent a circular to parents outlining plans for the entire school to evacuate the city and relocate to Bangor, North Wales. The plans included such details as the times of trains leaving Lime Street station on the evacuation days and the clothing to be included in boys' luggage. School was recalled on 21 August, the Declaration of War on Germany was announced on 3 September, and the evacuation of pupils began the same day.

An article about the evacuation from the December 1939 edition of Esmeduna, describes a remarkably orderly and enjoyable move, "Few will forget that memorable journey with its queer fusion of unreality and vividness. With the courage and happy thoughtlessness of youth, the atmosphere was rather one of a holiday picnic than a sad parting."[3] The account details the warm welcome extended to pupils in Bangor, their dispersal to billets, the glorious weather and outdoor activities such as cycle rides, fishing and swimming. After three weeks organisation, with lorries and cars having transported vital equipment from Liverpool, lessons took place at the Friar's Junior School, the local Youth Hostel and the Twrgwyn Chapel.

The initial euphoria seems to have been short-lived. There were problems with billeting, and with parents inflicting themselves on harassed hosts during impromptu visits to their sons. After Christmas, the military inactivity of the Phoney War was encouraging many boys to return home to Liverpool. The Collegiate re-opened and two women teachers were appointed for the first time. Evacuee numbers became depleted ahead of a larger return in late Spring with a mere 50 boys staying on in Bangor. The evacuation appears to have contributed to Gibson suffering stress-related illness, and he never fully returned to duties.

Ironically the return occurred just as military hostilities began to increase. Air-raids took place from August 1940 and Merseyside was to become the most heavily bombed area of the country outside London. The Collegiate itself very nearly became a casualty of The Blitz. In 1936, the annual Founders Day Service had been held for the first time at the neighbouring St. Augustine's Church on the opposite side of College Road North. Five years later, on 4 May 1941, the Collegiate narrowly escaped a Luftwaffe bomb which instead destroyed St Augustine's.

In 1943, the closing of Oulton High School and the merging of its pupils into the Collegiate, was accompanied by the installation of its head, W. J. R. Gibbs, as temporary headmaster of the Collegiate until his retirement in 1947. Gibbs set up a House System during the evacuation and had formed an active Parents' Association. He also started Parents' Nights to foster closer links between the school and the home.

In 1947, Kenneth A. Crofts who had been vice-principal since 1938, was appointed headmaster. Crofts was a Quaker and pacifist, which may explain why he was not offered the headship in wartime, and although the author of the Collegiate School history, H. S. Corran, "presumes he did not approve of the Cadet Force",[4] the headmaster's pragmatism, or his laissez-faire management style, enabled the school's CCF to continue unabated and, at a time when schools routinely used corporal punishment, the cane continued to be used for more serious indiscipline.

The Education Act 1944 abolished fee-paying at state grammar schools and ensured that the Collegiate took only pupils who passed the 11 Plus examination. Amidst post-war austerity, plans for a new Collegiate in West Derby appeared to evaporate, and Crofts believed that "the old building had many years of life before it still".[5] Renovation work including electrical rewiring and the installation of hot water began in 1950. New showers were built at Holly Lodge, and from 1954 additional playing fields at Leyfield Road, West Derby were provided for rugby and athletics. Summer camps on the Isle of Man were resumed in 1949 and would continue into the seventies. Annual school plays and musicals continued to be an important part of Collegiate life, as were concert performances including guest appearances by the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra who had rehearsed at the school before the Philharmonic Hall was built in the late 1930s.

Even before the 1950s concerns about falling standards were being voiced as pre-war expectations were changing and being challenged. Throughout the decade and beyond, the headmaster continued to measure academic success largely by the places his pupils secured at Oxford and Cambridge, while the academic success of the majority of pupils, despite Gibson's concerns in the 1930s, could be regarded as average. The rise in disciplinary incidents led to Punishment Schools taking place in two rooms when more than 40 boys were kept behind, each with two masters in attendance. A Swedish visitor to the school in 1950 regarded the Prefect System as similar to those in Sweden, though less democratic, but was surprised to witness corporal punishment being administered by Collegiate prefects. The prefectorial practice of 'slippering', whacking miscreants on the backside with a plimsoll shoe, would continue for two more decades. In 1959 the School Regulations were printed out and distributed for the first time. Initially this code of conduct included school uniform requirements, information about games, homework, school meals and a request for a School Fund contribution of 2/- (two shillings) per term. As more information about behavioural expectations were added, copying out the School Rules would outstrip lines as the preferred punishment for minor misdeeds.

At Speech Day in 1959, Crofts was reporting good A level and mediocre O level results, and that the average age of Collegiate staff had fallen with younger teachers bringing new activities and vitality to the school. He was also still hopeful that a new Collegiate could be built, complaining that the existing building was used as a playground at weekends. By 1961 all plans for the relocation of the Collegiate appear to have finally been scrapped, though the headmaster repeatedly seemed hopeful that work on a new building was about to commence.

In 1962, 'armorial bearings' were granted to the school by the Kings of Arms, an honour authorised by the Crown and bestowed on relatively few schools. The new coat of arms was designed by H. Ellis Tomlinson, one of the country's leading heraldic experts and a French teacher at Baines' Grammar School in Poulton-le-Fylde. The original motto, still on display in the mosaic tile badge in the Collegiate entrance hall, was retained and reads 'Ut Olim Ingenii Necnon Virtutis Cultores' which can be translated as 'When you have Knowledge also Cultivate Wisdom'. The simplified 'Knowledge is Responsibility' appears on some early school medals awarded for academic success.

In 1963 the Liverpool Education Committee announced its intention to abolish the 11 Plus examination and for the Collegiate to become a six form entry comprehensive school. Although several detailed plans were discussed and the long-term intentions of the LEA were clear, the proposals appeared to stall and the Collegiate carried on operating normally. Renovation work and improvements to the building took place in the mid 1960s, and throughout the decade concerts, school plays and productions of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas continued as usual. There were school trips to Switzerland for the skiing, Hadrian's Wall, Derbyshire, Yugoslavia, and to a kibbutz in Israel. The school camp at Kirk Michael, Isle of Man was augmented by another at Colomendy in North Wales.

In 1967 following Crofts's retirement, the post of headmaster was awarded to Cyril R. Woodward, the vice-principal, English teacher and rugby enthusiast who first came to the school in 1946. In December, Esmeduna contained a school survey which included the religious background of the 180 new intake pupils, or 'Newts' as they were called. Over 80 of the new first years were from Roman Catholic families, which may seem surprising given that the original Collegiate Institution had been affiliated to the Church of England and this was still the case after the LEA assumed control in 1908. Yet the school had always attracted other denominations; the evacuation circular sent out in 1939, for instance, had included information for the parents of Jewish boys at the school. The survey also recorded that 60% of boys never went to church, and a further 25% did so only for special occasions such as weddings.

By the end of a decade of major social change, the Collegiate had at least offered pupils guitar lessons and tolerated a progressive rock society. The Christian Union's penny paper, The Torch, had begun putting searching questions to staff and, in an interview with Head of Science Maurice Derbyshire in 1969, unearthed a little-known school war cry:

Boomerang-er, Boomerang-er, Boom, Boom, Boom;

Chickeracka, Chickeracka, Chow, Chow, Chow;

Ooh, Ah, Ooh, Ah, Ah, Col, Col, Collegiate!

In February 1970 the mantle of investigative, grassroots journalism was duly taken up by The Commentator which also became an active promoter of sports events, competitions and the Film Club. The school's traditional form structure was also being reviewed at this time; the antiquated grammar school form names consisted of: Third forms (First Year of secondary school), Fourth forms (second year), Removes (third year), Shells (fourth years) and Fifths. This path however appears to have allowed for the flexibility suggested by Gibson in the 1930s, and more academic pupils could, for instance, skip their fourth year Shell form. After the fifth year, Transitus (Trans) forms existed to provide a second chance for boys who underachieved at O Level. The Upper School consisted of 6β (6 beta, lower sixth form) and 6α (6 alpha, upper sixth form).

By the 1970s the school was smaller with fewer staff and boys, and reduced funding. An increase in reported cases of indiscipline, including several violent incidents, were causing concern, as were four break-ins which resulted in theft from the tuck shop, school office, staff room, and an attempt to enter CCF armoury. A School Council was set up in 1970 to enable pupils to have a say in decision-making. From 1971, the school magazine Esmeduna would only be published once a year instead of twice, and school dinners adopted a cafeteria system to offer more choice. In June 1972, the Liverpool Education Committee banned all forms of corporal punishment in the city's schools, although both cane and slipper appear to have continued in common use throughout the seventies. In September the school received formal notice that it was to be reorganised as a comprehensive school for boys, having a 5 form entry admitted on a non-local, non-selective basis.

The Comprehensive School years

Summarize

Perspective

Despite struggles with the local council and the Secretary of State, in 1973 the Collegiate became a comprehensive school that would provide education for around 900 boys. Initially, the only noticeable difference was that the building itself was cleaned with sand and detergent and its exterior changed from black to the original sandstone colour. School life carried on almost as normal, although C.R. Woodward announced his resignation as headmaster. Outwardly supportive of the move to comprehensive status, it seems that Woodward did not relish presiding over such monumental change and took up a lecturing position at a college in the south of England. The vice-principal, Ellis Clarke, a French teacher and rugby fanatic who had taught at the school since 1955, was appointed headmaster.

School sports teams, clubs and societies, including long-standing Collegiate traditions such as the Gild debating society and the CCF, continued to thrive throughout the increasingly challenging decade of Clarke's headship. Review magazine flew the flag for pupil journalism after the Commentator's demise in 1974, though Esmeduna produced its final edition in 1978. A Parent Teacher Association was set up, also a Remedial Department to address the needs of the less academic boys now entering the school.

Rumours about the future of the school and the lack of investment in the building suggested that upgrades which had been promised might not happen. Amidst difficult economic conditions and an inner city environment which was becoming more and more depressed, the Collegiate, regarded by some as a symbol of outmoded privilege, was becoming a political pawn in an increasingly political city.

As O and A level results deteriorated, as well as growing apathy from parents and a falling register, there were also numerous break–ins and vandalising of the organ. The future of the school looked gloomy. In 1980 the O and A level results were the poorest ever recorded at the school and the annual Prize Giving was marred by incidents before and after the event with some Collegiate boys being attacked by gangs of youths. The following year, the guest of honour was ex-pupil Leonard Rossiter and the event was prudently held in the afternoon.

The school premises were in a bad state of repair. Asbestos lagging needed to be replaced, leading to an early end to term, and in 1983 the turrets on top of the school were declared unsafe. In September 1982 the Liverpool Echo had run a story about future plans for the city's schools which suggested that the Collegiate might be closed, and in 1983 the city announced its plan to replace secondary schools with 'community schools'; the Collegiate would be closed and its pupils moved to Breckfield Community Comprehensive School.

Plans for reorganisation were set but before formal closure could be effected, fate intervened. On Friday 8 March 1985 a fire, apparently due to an electrical fault in the kitchens below the school hall, ravaged the building. Luckily all 530 pupils were evacuated and no casualties were reported but all three floors above the dining hall were destroyed.

Brian Fitton, a history teacher at the school from 1962, remembers events this way:

By the 1980s the Collegiate’s intake had been transformed. There was still a strong nucleus of ability but also a large number of 'problem' boys. The building was not ideally suited to a comprehensive school. The Collegiate’s days were clearly numbered and reorganisation in 1984 came as a relief to some, a chance to escape at last! After the fire the school continued to function, as part of Breckfield Comprehensive. Collegiate Old Boys could not imagine the appalling conditions then endured by the boys and staff who were left. Most staff (the lucky ones?) were distributed throughout the city. Many boys left for more settled schools, leaving the Collegiate half empty. Buses took boys to Breckfield for dinner—on one occasion the Collegiate boys, who now included large numbers of black boys from the Toxteth area, were viciously attacked by a racist mob as they got off the bus outside Breckfield. The Collegiate building never lost the smell of smoke. Pigeons in their hundreds (and some kestrels!) colonised the boarded-up windows. Staff had to commute between the Collegiate and Breckfield sites. As I look back I wonder how we (staff & boys) managed to put up with it. The final closure in 1987 could not come too soon![6]

No matter what political machinations were taking place, in the end the fire destroyed the school. Henceforth the building could only partially be used. The school was already in the process of amalgamating, and lessons were increasingly transferred to Breckfield Comprehensive, which did please some pupils as they had their first experience of mixed classes. The Collegiate was completely closed up in 1987 and the building left to deteriorate.

The empty shell of the school fell foul to looters and vandals. Two further fires, the last on 19 October 1994, gutted the dilapidated interior, and although a grant of £250,000 from Inner City Enterprises had been scheduled to repair the roof, the Collegiate now appeared impossible to save.

Rebirth

The decaying Collegiate was a great embarrassment to the city and there were many conspiracy theories explaining why the listed building was being allowed to deteriorate. Several refurbishment schemes were proposed and further water damage hindered progress. Finally in 1998, regeneration specialists Urban Splash and architects ShedKM submitted a successful £9M plan, approved by the city council and English Heritage, to turn the school into designer apartments. Although much of the interior was beyond repair, the entrance hall was restored, including the mosaic tiled Collegiate badge; the stunning façade and sides of the building were restored and a walled garden was created from the surviving walls of the school hall. The school finally re-opened on 12 October 2000, comprising 96 one, two and three bedroom apartments. The project was totally completed in May 2001 and received an RIBA Housing award in 2002.

Thereafter

The Collegiate Old Boys' Association,[7] set up in 1909, thrives to this day, though the original annual subscription of 2/6d (12½p) has increased to £10, with a Life Membership costing £90. It hosts an Annual Dinner, issues a yearly Newsletter to members, and maintains an informative website. The Collegiate Old Boys FC run five soccer Saturday Teams and two Sunday Teams, and the association also has an active Golf Society. Liverpool Collegiate RUFC is an autonomous rugby club which was formed by ex-pupils in 1925, became independent in 1958 and continues to field senior, veteran and youth teams. Dying Breed magazine was published by Len Horridge between 1999 and 2003 to provide a vehicle for sharing the memories and memorabilia of ex-pupils.

Notable former pupils

This article's list of alumni may not follow Wikipedia's verifiability policy. (February 2021) |

- Cyril Abraham, creator and writer of The Onedin Line

- Jack Balmer, captain of Liverpool FC

- Pete Best, musician, Beatles' original drummer

- Anthony Bevins, journalist

- Reginald Bevins, MP and Postmaster-General

- Cyril Bibby, biologist and educator

- Billy Butler, DJ and broadcaster

- John James Clark, architect

- Basil Ellenbogen, British Army officer and consultant physician

- Gershon Ellenbogen, barrister, author and Liberal Party politician

- Tom Farrell, Olympic hurdler

- Philip Fox, actor

- Del Henney, actor[8]

- William Hughes, university professor and author

- Alfred William Hunt, painter associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

- Holly Johnson, lead singer, Frankie Goes to Hollywood

- Sam Kelly, actor, Porridge and 'Allo 'Allo!

- Brian Labone, footballer, Everton and England

- Gregory B. Lee, Founding Professor of Chinese Studies, University of St Andrews

- Ralph P. Martin, New Testament scholar

- Sir John Nicholls, air marshal

- Eddie O'Hara, MP

- Nigel Parkinson, cartoonist

- David Daiches Raphael, philosopher, university professor and author

- Ted Ray, comedian

- Sir Ken Robinson, author and arts educationalist

- Leonard Rossiter, actor, Rising Damp and The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin

- Ian Venables, composer

- Sir Charles William Wilson, geographer

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.