Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Achomi people

Ethnic group of Persian and Iranic people From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Achomi people (Persian: اَچُمِنیان, Gulf Arabic: اتْشُم/اتْشَم, Inscription Parsig: 𐭠𐭰𐭬𐭭𐭩𐭠),[4][5][6][7] known by their self-designated pseudonym as Khodmooni (Persian: خُودمونی),[4][5][6][7][8] commonly known as Laris (Farsi: لاریها),[1][9] Larestanis (Persian: لآرِستَانِیها),[4][9][5]are a Persian and Iranic group said to be descended mainly of Utians,[7]: 5 and/or of a tribe of Persians known as "Ira" (Persian: ارا) according to Sasanian sources,[10] who primarily inhabited southern Iran in a region historically known as Irahistan (presently Larestan region),[11]: 228 [7][10] some of them migrated to Shiraz,[8] and the Arab countries in the Persian Gulf region.[8][12][13][14] They speak the Achomi language which has reported eight dialects and it is unintelligible with New Persian/Farsi, (Dari, Tajiki, and Iranian).[15][16] They are predominantly Sunni Muslims,[17][7] with a Shia minority.[17][7]

Remove ads

Origins

Summarize

Perspective

The Achum/Acham people are said to be of Persian/Parsi (پارسی) descent.[7][18]

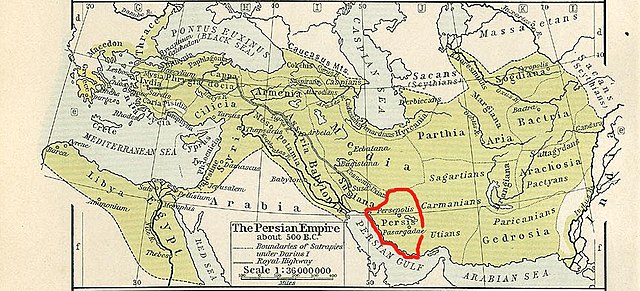

In the Achemaenid Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great, a land in Southern Persis called "Vautiya" or "Yautiya" is described. Leading scholars to believe that might they be the same as the homeland of the people Herodotus called "Utians".[19][20][21][22]

Author Mehran Kokherdi suggests that Achomis/Khodmoonis; mainly have their roots in Utians with possible Persian, Parthian, Jewish, Scythian, and Indian/Dravidian influences.[7]: 5

According to later Sassanian sources, Irahistan was inhabited by an ancient Persian tribe known as "Ara" or "Ira" or "Irah" people, which are said to be a large tribe of Persians (Parsis) of Aryan origins.[10][additional citation(s) needed]

Similarly to the House of Sasan,[23] the later Lari-ruled Miladian dynasty which ruled Laristan during the Medieval Ages traced their origins to Gorgin Milad, a descendant of the cycle of the legendary Kay Khosrow of the Kayanian dynasty.[24]

According to local traditions, some Abbasid Khodmoonis claim an ancestral link to Ibn Abbas.[citation needed]

There is an ongoing genetic study project for the Achomi people.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Etymology

Summarize

Perspective

- Achom/Achum/Acham: In Avesta the holy book of Zoroastrianism, "Achum" (Persian: اَچُمِ) is one of the names of God (Ahuramazda), and it means "self created" and "without cause."[25] Native speakers often refer to their language as "ačomī", Achem (Farsi: اچِم) means "I go" in the language.[26] Other explanations for this name are the language's frequent usage of the [tʃ] consonant.[16] Arabs, with whom these people traded, called them 'Ajam', which means non-Arab, Masnsour (2003) believes that it was eventually changed into "Ajami" and "Achumi".[16][8] Thus it is very plausible that Achum,[25] evolved into Ajam.[8][16] possibly due to the initial non-existent "ch" character in Arabic (although Gulf Arabic does include "ch" «چ» and "ga-" «گ» sounds now).

- Khodmooni (Persian: خُودمونی): Achum/Acham people refer to themselves as Khodmooni, a term literally meaning "part of ourselves"[4][8] Their language is also sometimes referred to as Khodmooni.[12]

- Lari (Persian: لاری): This language is sometimes called Lari.[3][9] To reiterate, 'Lar' originates from 'Lad' which means "the origin of everything".[27] It is also important to note that Lari can be used to refer to a dialect (e.g. Lari dialect of Achomi/Lari/Khodmooni), the language itself,[9] or the people.[1]

The ancient Persians; not to be confused with present-day Persian-speaking people (Arabic: فُرس, romanized: Furs, Farsi: فارس, romanized: Fars) who are of diverse origins,[28][29] were an ancient Iranian people who migrated to the region of Persis (corresponding to the modern-day Iranian province of Fars) by the 9th century BCE.[30][31] The 1939 survey of ethnic groups in Iran, particularly Southern areas such as Laristan indicates the area is inhabited by Persians (Iranis) who work as farmers, whilst the coastal areas are inhabited by Sunni and Shia Arabs.[11]: 228 This may explain why the term "Ajam" stuck to the Achomis/Khodmoonis in the Persian Gulf area.[8][7][32] Although in the Arab states in the Persian Gulf, this was later used to denote Non-Arabs of a Shia background particularly,[33] similarly to the modern usage of the word "Persian".[34]: 27 This was before the Persian nationalism of the former Pahlavi Dynasty and the concurrent Islamic Republic which have both attempted to erase ethnic diversity in Iran (the Kurds, Azeris, and Baluchs being the most affected), with many non-Persian minorities nowadays identifying as "Persian" now.[28][29]

In GCC states surrounding the Persian Gulf, Achum/Achams are referred to as Khodmooni'.[4][8][3] This translates to "of our own kind".[3][35] In the UAE and Qatar they are known as Ajam/Ajamis,[36][8] which is the standard name for GCC citizens of Iranian origin. In Bahrain Sunni Achum/Achams are referred to as "Huwala" (not to be confused with the Huwala Arabs),[32] and their language is sometimes referred to as "Holi,"[37] While Shia Achum/Achams are known as Ajam.[7][32] In Kuwait, they fall under the name 'Ayam which is what Kuwaitis of Iranian origin are called;[7][32] the Shia Achum/Acham are known as "Tarakma". The most notable Sunni family is Al-Kandari (Arabic: الكندري).

Remove ads

Language

Summarize

Perspective

The Achum/Achomi people speak the Achomi language, sometimes referred to as Lari,[9][38] or Larestani language.[3][38] The language has reported eight dialects (Bastaki, Evazi, Gerashi, Khonji, Ashkanani, Lari, ...)[39][12][40] and is mostly unintelligible with modern Persian (Farsi),[15][16] and is considered an unattested living branch of Middle "Pahlavi" Persian,[39][12][40] derived from various unattested Middle Persian (Parsig) dialects spoken by the Zoroastrian and Jewish inhabitants of Fārs province prior to the spread of New Persian (Farsi).[41] The UNESCO website indicates that it has around a million speakers, and classifies it as an endangered language,[3] whilst the Ethnologue website indicates it has 10k to 1 Million speakers.[2]

They additionally speak Farsi as the official language in Iran. In Gulf GCC countries they speak Gulf Arabic (Bahraini, Kuwaiti, Emirati, etc...) along with Achomi,[39][12][40][15][42] some of them also speak English fluently.[43] Some Achomis in Bahrain speak a local "Bushehri derived" dialect of Farsi; which was formed by socializing with Bushehris (Lurs/Ajams, and minority Arabs, etc...).[citation needed] Mainly in part due to the fact that the migration from Bushehr, Bander Abbas, Bander Lingah, happened around the same time.[13][44]: 60

The Achomi language is in decline,[3][2] mainly due to the Farsification process aka dominating Iranian, Tehrani New Persian (Farsi) and Identity in Iran,[26][45][28][29] which was a nationalist ideology invented by the Pahlavi regime, influenced by Aryanism, which sought to erase ethnic and linguistic diversity in favour of an exclusivist Persian identity,[28] further affirmed by the Islamic Republic,[29] similarly Arabization (dominating and imposed Arab identity and Gulf Arabic language) in some of the Arab Gulf states,[44]: 72 [44]: 49 [46][47] which in Bahrain was a gradual process initiated by the British protectorate,[47] With no effort being made by either side to preserve this language beside the national language.[citation needed] Despite this, the language is still spoken widely even in the Gulf countries to some extent.[12][40][15][5]

Remove ads

Religion

Summarize

Perspective

Presently they are now mostly Sunni Muslims,[17][7] with a minority of Shia Muslims,[17][7] and possibly a small number of Jewish (immigrant) survivors,[41] and non-religious ones.[48]: 42

Prior to Islam, the Achum people were on the Zoroastrian Religion.[41][additional citation(s) needed]

Later, Lar was likely a Jewish settlement, a group of people from Lar followed Judaism,[49][41] they were described in 1523 as "poor people, native to the same land" by A. Tenreiro,[49] they got wealthier and larger in number in the first half of the 16th century due to the arrival of Sephardic Jews, attracted via Hormuz[41][additional citation(s) needed] . With these groups came commercial contacts and this had brought Lar the reputation of a "seat of wealthy merchants." In the course of the 17th century, however, important sections of this community moved to the new Safavid capital, Isfahan.[49]

Lar hosted a prosperous Jewish community as early as the 16th century.[49] The French traveler Jean-Baptiste Thévenot reported that when he visited Larestan in 1687, most of Lar's inhabitants were Jewish silk farmers. Additionally, a Spaniard who visited the town in 1607 met a "messenger from Zion" named Judah. However, like other Jewish communities in Persia (except the Georgian Jewish deportees employed as silk worm farmers in Māzanderān), the Jews of Lar suffered under the Safavid rulers during the 17th and early 18th centuries. According to the Judeo-Persian chronicler Bābāi ibn Luṭf, persecutions began before 1613 during the reign of Shāh Abbās I and originated in Lar, where a local rabbi converted to Islam and took the name Abul-Hasan Lāri. This converted rabbi secured a royal edict (farmān) requiring every Jew in Persia to wear discriminatory badges and headgear, which led to the mass expulsion of hundreds of Jews from Isfahan due to their perceived "impurity."[41]

The Jews of Lar resided in cities such as Lar, Juyom, Banaruiyeh, and Galehdar but later migrated to Shiraz, Tehran, and Isfahan. Many of them also emigrated—primarily to Israel, and a smaller number to the United States and other Western countries. The Jewish population of Galehdar entirely relocated to Israel at the time of its establishment, while Jews from Juyom, Banaruiyeh, and Lar settled in various locations as mentioned. Some Jewish families in Lar did not emigrate and remain there today [41][additional citation(s) needed] . The estimated population of Khodmooni Jews is around 100 families.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Geographical distribution

Summarize

Perspective

The historical region of Irahistan consisted of several counties in:

- Hormozgan province: Parsian, Bastak (Central, Kuhij, Kukherdharang, Jenah, Kukherd), Bander Langeh, Khamir, Bandar Abbas, Hajjiabad, Rudan, Minab, Sirik, parts of Bashagard, and Jask.[50][51][52][53]

- Fars: Mohr, Khonj, Lamerd, Gerash, Evaz, Juyom, Zarrin Dasht, Darab, Larestan.[50][51][52][53]

- Bushehr province: Asaluyeh, Jam, Deir.[50][51][52][53]

- Part of Kerman province.[50][51][52][53]

Presently, most Laris/Achomis/Khodmoonis inhabit the historical Larestan region,[26] which encompasses the areas of Lar, Gerash, Evaz, Khonj, Bastak, Lamerd, and surrounding villages and settlements in southern Fars Province and northern Hormozgan Province.[citation needed]

However, since the 1940s, due to the combination of harsh natural conditions and political factors has compelled the Garmsiris (Laris/Achomis/Khodmoonis) to emigrate, to earn a better living,[13] avoid the harsh nature,[8] and to avoid the Iranian central government imposed new import and export taxes.[4][8][13][14] often moving northward to Shiraz,[8] but more commonly heading south toward the coast,[8] and further to India and the Arab countries in the Persian Gulf (UAE, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and other Arab states of the Persian Gulf).[8][14][13][12][40][37] In 1955, the Larestani scholar Ahmad Iqtidari (Persian: احمد اقتداری) eloquently captured the plight of his homeland in his book Ancient Larestan (Persian: لارِستان کُهَن), to which he dedicated his work:[8]

To those people of the towns, villages, and ports of Larestan who have stayed in the land of their ancestors, with its glorious past and its desolate present. And to those who have endured the hardship of migration to earn a living on the islands of the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean and in the towns of India, Arabia and other places. They remember with joy their beloved birthplace and still grieve for its ruin.

— Ahmad Eghtedari, Ancient Larestan (1955)

Remove ads

Sub-groups

The main Khodmooni branches are as follows:

- Lari لاری

- Bastaki بستکی

- Khonji خنجی

- Gerashi گراشی

- Evazi اوزی

- Eshkanani/Askhanani اشکنانی

- Aheli اهیلی

- Galedari/GallehDari گلهداری

- Lengeyi لنگیی

- Ashnezi اشنیزی

- Ruydari رویداری

- Abbasi عباسی or Gamberoni گمبرونی; aka Bandari بندری

Some ethnic groups are considered to be sub-groups or related to Achomis/Khodmoonis:

- The Gallahdaris (known as Persian: بیخیها, lit. 'Bikhis') are of mixed Achomi and Luri ancestry and possibly Circassian ancestry, due to historical reasons of migrations that occurred,[54][additional citation(s) needed]

- The inhabitants of Minab are said to be of mixed Arab, Persian, Baloch, and Sub-Saharan African descent.[11]: 228–229

- Lamerdis are a mixture of Lurs, and Achomis/Khodmoonis, they speak a mixed dialect of Persian, Luri and Achomi.[citation needed]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The Irahistan/Laristan region was nearly always an obscure region, never becoming involved in the politics and conflicts of mainstream Persia.[9] This was due to independent rule during the Safavid times, but that has failed due to the British Empire "Anti Piracy Company" and continued to decline due to Reza Shah's centric policies and the Ayatollah policies.[8]

Pre-Islamic times

The Achaemenid royal Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great mentions a land in the southern Persia (Persis) known as "Vautiya" or "Yautiya" which scholars believe is one and the same as the people Herodotus called "Utians",[19][20][21][22] who are believed to be the primary ancestors of the Achomis/Khodmoonis.[7]: 5

In "Kar-Namag i Ardashir i Pabagan," a book written in Middle Persian (Parsig), the name of Irahistan is mentioned in the section describing the second war between Ardeshir and Haftvad:[55]

The army wanted to go to the court and rushed to the campaign of Kerman with a large army. And when he approached the fortress, the army of Kerman all sat inside the fortress and Ardashir surrounded the fortress. Haftan Bakhtar had seven sons. He had assigned each of them to a city with a thousand men, and at this time one of them, who was in Irahistan, came to Kerman with a large army of greyhounds and Omanis across the sea and fought against Ardashir.

7th-14th Century

The first Lari prince to convert to Islam was Jalal al-Din Iradj, who converted around 100 A.H, (718–19).[56]

From the early 12th century, Laristan was being ruled by the local Miladian dynasty.

In the thirteenth century, Lar briefly became a centre of trade and commerce in southern Persia.[9]

Ibn Battuta's Travelogue

Ibn Battuta entered the city of Khonj in 733 AH and wrote about the piety and asceticism of the people and his meeting with the religious hermitage at the time. He travelled through the Dhofar region (modern Oman) and arrived at the island of Hormuz, entering the Laristan area. He passed through the cities of Minab, Rudan, Kuhoristan, Kookherd, Laro, and Khonj. Here is an excerpt from his travelogue:[57]

I came to Lar via India, and together with Abu Zayd Abdulrahman ibn Abu Dolaf Hanfi, we entered Khonj in 733 AH. I heard that there was another hermitage in Khonj (likely referring to Sheikh Abdul Salam's hermitage). It was inhabited by righteous people and worshipers. I visited them at night. There was a noble man whose devotion was visible on his face. They had yellowish complexions, frail bodies, and tear-filled eyes. When I entered the hermitage, they brought food. He called out to the elders of the community to call my son, Mohammad (referring to Sheikh Haji Mohammad, the son of Sheikh Abdul Salam), to come. Mohammad, sitting in a corner, rose, appearing so frail from his devotion that it seemed as if he had risen from the grave. He greeted me and sat down. The elder said, 'Son! Join us in the meal so that you may share in their blessings.' Mohammad, who was fasting, joined us and broke his fast with us. This group was all Shafi'i in their beliefs. After the meal, prayers were performed, and we returned to our place.

Marco Polo's travelogue

Marco Polo described the Hormuz Plain and the Minab River as a lush, fruitful region, diverse in its offerings. Hormuz, an ancient area, was a place of trade between the Persian Gulf merchants and Kish. Marco Polo noted the significance of the port of Hormuz and its trade with Indian merchants, with large ships carrying spices and pearls. This region was popularly known as "Daqyanus City" among the locals, and its ruins are believed to be located in the northern part of Jiroft today. Marco Polo also commented on the shipbuilding industry in Iran at the time, criticizing the lack of tar on the ships, which he believed led to many of them sinking. Another interesting detail he mentioned was the intense, often deadly seasonal winds in the area, known as Teshbada.[58]

15th-17th Century

During Safavid Iran

According to an anecdotal account shared on a blog (Sons of Sunnah), when the Safavid dynasty under Ismail I initiated efforts to convert Iran's population to Shia Islam in 1501, some Sunni Persians allegedly fled to the Zagros Mountains to escape persecution. Following the Battle of Chaldiran, these Sunni Persians reportedly descended to settle in a region they named 'Bastak,' said to signify a 'barrier' against Shia Safavid influences.[59]

The region of Irahistan was ruled by local lords until they were removed by the Safavids in 1610.[60] Shah Abbas I ruled from til 1629 CE (1038 AH).[citation needed]

After the fall of Isfahan to Mahmud Khan of Afghanistan in 1722 CE (1135 AH), the Afghan rule lasted until the rise of Nader Shah, who re-established Persian control in 1736 CE (1149 AH). During this time, Bastak became the center of the region.[citation needed]

Under Afsharid Iran

Jangiriyeh under Sheikh Ahmad Madani: The Afghan period and the early years of Nader Shah's reign, likely between 1720s to 1740s CE.[citation needed]

Hassan Khan Delar ruled during the mid-18th century, particularly after Nader Shah's death in 1747 CE (1160 AH).[citation needed]

18th–19th Century

Zand Dynasty

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (April 2025) |

The Bani Abbas family ruled the region during the late 18th century and early 19th century, likely under the Zand dynasty (from the late 1700s until the early 1800s). The rule of the Bani Abbas continued until the land reform era in early 20th century.[citation needed]

Qajar Iran

Larestan

In the second half of the 13th century AH (late 19th century CE), the governance of Larestan was entrusted to the Dehbashi family, one of the prominent families of Gerash. This family ruled Larestan for approximately a century, beginning in 1262 AH (1846 CE) under Karbala'i Alireza Dehbashi. During the tenure of his son, Fath Ali Khan Biglarbeigi, Larestan experienced its most prosperous period in both military and economic aspects.[61]: 343–344 Fath Ali Khan established strong ties with the influential Qavam family in Shiraz and maintained favourable relations with the Qajar dynasty in Tehran, which helped him expand and solidify his authority.[62]

The political and security stability achieved during Fath Ali Khan Gerashi's rule brought significant advancements in the scientific and literary domains. Early in his reign, Shaykh 'Ali Rashti, a mujtahid from Najaf, was sent to Gerash by Mirza Shirazi to establish a seminary. This period saw cultural enrichment, including the production of religious and mystical writings by Haj Asadullah, the brother of Fath Ali Khan, and Shaykh 'Ali Rashti. Additionally, Rostam Khan Gerashi, the son of Fath Ali Khan and father of Mohammad Jafar Khan (Sheyda Gerashi), compiled a poetic collection titled Baghestan. Mohammad Jafar Khan later contributed his own collection of poetry, further cementing the literary heritage of the period.[61]: 59–60

Muhammad Ja'far Khan (Sheyda Gerashi) ruled the whole of Larestan and the ports of the Persian Gulf in two periods: first after his father, Rostam Khan, and from 1327 to 1329 AH (1909–1912 CE), after which he was angered by Habibullah Khan Qavam al-Mulk, the ruler of Fars, and lived in exile in Narenjestan Qavam of Shiraz. During this period of his reign, his cousin, Hasan Quli Khan, was his viceroy in Gerash.[63]: 172–177 After the death of Habibullah Khan in 1334/1935 and the accession of his son Ibrahim Khan to the government of Fars province, Muhammad Ja'far Khan was released and returned to Gerash. However, the beginning of his second reign has been mentioned in various books from 1332 or 1333 AH.[61]: 346 [63]: 172 In this period, which lasted until the end of his life in 1338/1939, he was in charge of the Gerash and its castle as well as the endowments left over from Fath Ali Khan Gerashi after his father, Rostam Khan.[61]: 371 [64]: 9 After him, and during the period between the two periods of Muhammad Ja'far Khan's rule, the government of Larestan was in the hands of Ali Muhammad Khan Iqtadar al-Sultan.[61]: 346

Mohammad Jafar Khan, as the ruler of Gerash, traveled to the Sahra-ye Bagh district at the request of Ebrahim Khan Qavam-al-Molk, the governor of Fars, to mediate conflicts between the Shia Lor-e-Nafar tribes and the Sunni residents of the region.[64] On 12 Rajab 1338 AH (April 19, 1920 CE), near the village of Dideban, he was shot and wounded by Yousef Beyg Nafar, a leader of the Lor-e-Nafar tribe.[63]: 173–174 He survived for two days but ultimately died on Sunday, 14 Rajab 1338 AH (April 21, 1920 CE), before reaching the age of 42. As per his will, his body was transported to Gerash and placed in dokhmeh.[63]: 175

Thirty-eight years later, his remains were moved to Karbala by a man named Seyed Kazem and buried behind the shrine of Imam Hussein. According to one account, his body was still intact when it was exhumed, to the extent that even the color of the henna from his second marriage ceremony—held just days before his death—was still visible on his hand.[63]: 175 During a visit to his grandfather's (Sheyda Gerashi) tomb in 1346 SH (1967 CE), Ahmad Eghtedari described the grave marker as illegible.[65]: 132

After the establishment of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (early 20th century CE), the Dehbashi family retained their hold on Larestan, navigating alliances with constitutionalists to maintain their rule. However, the dynasty's governance came to an end in 1929 CE (1348 AH) when Reza Shah's army attacked Gerash Castle, marking the conclusion of their reign.[61]: 61

Bastak and Jahangiriyeh

Mohammad Taqi Khan, son of Mostafa Khan, known as "Solat al-Molk," (born in 1272 AH; 1855 CE) in Bastak served as the ruler of Bastak and Jahangiriyeh for 41 years (1305 AH; 1887 CE – 1346 AH; 1927 CE).[66][67] Mohammad Taqi Khan died at the age of 74 in 1346 AH (1927 CE), coinciding with the second year of the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi, in his personal garden in Makhdan Bastak and was buried in Bastak Cemetery.[66] He was succeeded by his son Mohammed Reza-Khan Bastaki (known as "Satout Al-Malik").[66]

20th Century ~ Present

Since the 1940s, due to the combination of harsh natural conditions and political factors has compelled the Garmsiris (Achomis/Khodmoonis) to emigrate, often moving northward to Shiraz,[8] but more commonly heading south toward the coast,[8] and further to India and the Arab countries in the Persian Gulf (UAE, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and other Arab states of the Persian Gulf).[4][14][13][8]

Migration to GCC Countries

Between the 19th and 20th centuries, many Achumi merchants have migrated to GCC Countries, to earn a better living,[13] avoid the harsh nature,[8] and to avoid the Iranian central government imposed new import and export taxes.[4][8][13][14] The introduction of taxes was an effort to reinforce the authority of the Iranian state and draw revenue from affluent peripheral areas like Bandar Lingeh and Bushehr, which were key economic hubs in the Persian Gulf during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[13][8] Migrants, familiar with the region, circumvented these restrictions by choosing alternative routes.[13] To escape the heavy taxation, many merchants simply relocated to the other side, a practice that had been common for centuries due to the familiarity of the region,[14] prompting the migration of tens of thousands of people from southern Iran to the opposite shores.[14] Bahrain,[13][12][40] and UAE,[8][12][40] Qatar,[12][40] Oman,[12][40] and Kuwait,[12][40] became a primary destination for these migrants,[13] leading to a significant increase in their Iranian population.[13] This period also saw heightened British involvement in Bahrain.[14][13]

For centuries, transnational Sunni Arab families, as well as Sunni and Shia Persians, have migrated from southern Iran to the Arab coast of the Persian Gulf.[4] Coastal Iranian groups have historically been more closely connected to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) than to Iranian communities further inland (Potter, 2009).[4] These communities have maintained a "dual existence," often owning homes in multiple countries and speaking several languages (Nadjmabadi, 2010).[4] This transnational lifestyle has historically provided economic benefits to both Iran and the UAE, though it has been affected by recent political unrest in the region.[4]

Many Iranians and Emirati citizens of Iranian origin residing in Dubai and other UAE cities trace their roots to towns in the Larestan region (shahrestân) and the Hormozgân province of Iran.[4]

The shipping expertise of the Larestani/Achumi people, combined with their access to the lucrative markets of Africa and Asia, significantly influenced the development of Dubai's economy (Davidson, 2008). By the early 1900s, Dubai had established itself as the region's most attractive business hub, drawing skilled migrant entrepreneurs from the unstable Persian coast. This tradition of fostering entrepreneurship in the UAE predates the nation's oil exports (Davidson, 2008). During this period, approximately 30 of the most adaptable immigrant Iranian family businesses in Dubai gradually evolved into global conglomerates (Jaidah, 2008).[4]

When the Bastakis migrated south to Lengeh, they brought the architectural innovation of wind towers with them. Upon settling in Dubai, they carried this technology forward, constructing coral rock homes adorned with these elegant structures. In tribute to their homeland in Iran, they named their district in Dubai Bastakiya.[8]

However, there was a challenge: while wind towers are highly effective in dry, hot regions like Yazd, Kashan, and Bastak (and theoretically in places like Arizona) due to the rapid evaporation that facilitates cooling, they are less functional in the humid summer climates of both coasts of the Persian Gulf. While visually striking, the wind towers in such conditions are more decorative than practical.[8]

Beyond architecture, the Bastakis also introduced mahiyawa, a highly pungent sauce made from fermented fish and spices. It is typically enjoyed with fresh Bastaki bread. Though considered a delicacy by many, particularly among khodmooni families in Dubai, mahiyawa is very much an acquired taste. Achomis/Khodmoonis from Dubai often send bottles of it, emphasizing its cultural significance.[8]

Assimilation

In the GCC Region

In Dubai, the Al-Maktoum rulers welcomed newcomers for their wealth and trading expertise. Many thrived, with some engaging in Dubai's burgeoning "gold trade." Their success was further bolstered during the 1960s and 1970s by Sheikh Rashid's open-door commercial policies, which avoided favoritism toward Arabs and encouraged economic inclusivity.[8]

The Larestani/Achumi people have generally contributed greatly to the economy of Dubai, and are as such very well respected.[4]

However, not all interactions were positive. In 1904, anti-Persian rioting broke out in the markets of Manama, marking the first recorded instance of local resistance against migrants in Bahrain.[13] The British labeled the incident as "anti-Persian" and subsequently took control over the affairs of Iranian migrants in Bahrain.[13] In response, the Iranian central government requested British assistance to ensure justice for its citizens in Bahrain.[13] According to Lindsay Stephenson, speaker for Ajam Media Collective, this request was a temporary measure rather than an attempt to permanently cede jurisdiction, reflecting the historically fluid and overlapping borders in the Persian Gulf region.[13]

In 1928, violence erupted in Dubai against Iranian-origin merchants after the British intercepted a boat in the Persian Gulf carrying kidnapped women and children from Dubai to Iran. Suspicion fell on the British agent of Iraqi origin for inciting this unrest, necessitating British intervention to restore order. Additional challenges arose during the 1950s and 1960s with tensions fueled by Arab nationalist movements.[8]

In the 1950s the British protectorate started the gradual process of Arabizing the Persian locals.[47] The imposed Arab identity,[44]: 49–72 [46][47] much like the imposed Fars identity in Iran,[26][45] did not help in preserving the language in which is in decline,[3][2] but by any means, there still exists a minority of them that are bilingual and sometimes even trilingual Achomis who excel in Achomi,[37][15] Persian, Arabic,[42] and sometimes even English.[43] Those who do not speak it still held on to their khodmooni culture in the form of music and foods.[8]

Many Emiratis express discomfort not only with the significant number of foreign residents but also with the diversity within their own population.[8] They often assert, "We are all Arabs," while overlooking the influence of cultural and social currents from Iran and other regions that have shaped their society.[8] However, some, like writer Sultan Saud al-Qasimi, have embraced this diversity.[8] Al-Qasimi advocates for acknowledging the rich cultural tapestry of the UAE, stating, "It is high time that we recognize the contributions of the mosaic that forms this young nation. The Emiratis of Asian, Baluch, Zanzibari, Arab, and Persian origin make this country what it is today."[8]

In 2001, al-Qasimi underscored this appreciation of cultural heritage by naming his Dubai brokerage firm Barjeel (wind tower), a nod to the uniquely Iranian architectural feature that has become a distinctive part of the UAE's landscape.[8]

In Bahrain, they were all known as "Ajam."[46] Today, they are separated by religion. Sunni Achamis have abandoned the term "Ajam" and more commonly use the term "Huwala,"[68][69] based on the belief that "Ajam" refers to those with Shia roots,[33] which is generally a term denotes "non-Arab" and encompasses a broad range of meanings, Musa Al-Ansari states that this term originally referred to non-Arabs of a Persian-speaking (or derivative; i.e. Achumi) background as they were the only non-Arabic speakers in Bahrain, but due to the increase of other non-Arab/non-Arabic speaking ethnicities and people (such as Asians) he claims to have "reservations" to it due to its wide meaning.[34]: 27 Sunnis among them are said to not face any discrimination.[68][69] "Huwala" is a term used in some Gulf countries to describe people with Sunni ancestry from southern Iran, and it includes a significant population of such individuals.[68] These groups are descendants of Persians and Africans who migrated to the Arab countries of the Persian Gulf in the 19th century.[68] For someone to be recognized as Huwala, they do not need to officially follow the Sunni religion, but must have Sunni background from southern Iran, as their ancestors who migrated to the Gulf Arab countries were Sunni.[68] A person who is Sunni but has Shia ancestry from southern Iran is still recognized as "Ajam."[68] Some Arabs consider this a new identity fabrication for Sunni Persians, as they did not speak Arabic when they first arrived.[70]

With Northern Iranians

Many of the khodemooni express pride in their heritage but noted feeling little connection with "northern" Iranians.[8] This disconnect was not solely due to religious differences.[8] One Dubai merchant explained:[8]: 15

We can operate as far north as Shiraz. That is familiar territory. Above Shiraz is alien to us. When we do business there we inevitably get cheated. The mentality and the manners of the people there are like Persian carpets – too complicated. We have more in common with the Arabs, whom we know. Like us, they are straightforward people, without the complexes and complexities of Tehranis and Isfahanis.

— Iranian and Arab in the Gulf: Endangered Language, Windtowers, and Fish Sauce, Page 15

Remove ads

Culture

Summarize

Perspective

Local Calendar

The Achumi calendar is an agricultural calendar; although its oral version has no specific starting point and is primarily used for agricultural purposes, it aligns with the solar calendar.[71] The new year begins in mid-February, and its first month is "Naybahar," with the final month being "Borobar."

Music and dance

The people of Irahistan are known for their famous handkerchief dance, known as (Dastmal Bazi), also known as "Se Pah" (Persian: سِه پا, lit. 'three foot') where mostly the men dance,[72][73][74][75][7]: 177 the Bastaki variation being the most common,[76] even in Dubai,[77][78] and is similar to Bakhtiari dance, however, Lamerdi women have their own dance.[79] In an addition to that, the stick dance (Tarka bazi or Chob Bazi) is also common.[7]: 177 These dances are also popular among the Turks and Lurs in western Iran, though each ethnic group has its unique way of performing them.[7]: 177 Additionally, certain musical instruments are renowned in the region, such as the reed (Nay), bagpipe (Haban), tambourine (Daf), and lute (Oud). The Daf holds a special role in ceremonies celebrating births or weddings.[7]: 177

Yousif Hadi Bastaki (1937-2000)

Sultanies Band (1985-2006)

Arvin Bastaki

The Achomis/Khodmoonis have many local folkloric songs which have been sung by Yousif Hadi Bastaki, the Bahraini-Iranian band "Sultanies", and Arvin Bastaki, among other bands. Some of their iconic ethnic and folkloric songs include:

- Chayi Chayim Kelam Dard Akon (چایی چاییم کلهام درد اَکُن)[80][81]

- Raftum Be Baghe Shalom Darrideh (رفتُم به باغ شالُم دریده)

- Esmush Nadunem/Gol Bostanan (اِسمُش نادُنِم/گل بستانن) sung by Arvin Bastaki,[82] Yousif Hadi,[83][84] Sutlanies,[85] and is/was popular in Bander Abbas too.[86]

- Del Naghrah Del Naghrah Yaram Soraghm Naghrah (دل ناگره دل ناگره یارم سراغم ناگره)

- Esho Golom Shabran Jan Delom Shabran (اشو گلُم شبرِن جان دِلُم شبرِن)[87][88][89]

- Ey Vay Delom Vay Delom Delbar Zibai Delom (ای وای دلُم وای دِلُم دِلبَر زیبایی دِلُم)

- Delbari Man Che Khoshgelan Vay Vay Umnasha (دلبری من چه خوشگلن وای وای اومناشا)

- Dastband Tala Dastat Ghorbun Chesh Mastat (دستبند طلا دستات قربون چش مستات)

- Ching Bekenam, Ching Vakonam Chahare Delbar Nakonam (چینگ بکنم، چینگ واکُنِم چهاره دلبر ناکنم)[90]

- Dar Mawsam Beharan Del Shadom Ney (در موسم بهارن دل شادُم نی)

Cuisine

Khanfaroosh

Mahweh (Mahyaweh)

Ranginak

Balaleet

- Mahyawa (Mahuwa) – Fish Sauce: Mahyawa is a famous dish widely consumed in the southern regions of Fars province and Hormozgan (including Bushehr),[7]: 177 [8] as well GCC countries,[91][8] which has been introduced there by the Achomis/Khodmoonis.[8] It is made from a type of sardine fish, locally known as Hashineh, or other fish such as Balem or anchovies (Moto).[7]: 177 The exact origins of this dish or how it spread are unclear, but it is evident that the inhabitants of inland areas developed methods to preserve fish and other foodstuffs, such as drying and salting, to prevent spoilage.[7]: 177 The Achum, or the people of Irahistan, are considered among the most skilled in preparing Mahyawa according to its traditional standards, which serves as evidence of their pioneering role in creating this unique dish.[7]: 177 In the Achumi language, the word Mahyawa is pronounced Mahuwa, derived from the two words Mi (fish) and Awa (water).[7]: 177

- Noun Falazi (Arabic: خبز فلزي, romanized: Khobz Falazi, Persian: نان فلزی, romanized: Nan Falazi) is a type of local bread known for its high quality, made in the village of Kookhord, located in the Kookhord district of Bastak County. It is also found in other regions of Bastak, Laristan, Gerash, Ouz, Khenj, and Beghard in southern Iran. "Noun Falazi" is a popular and high-quality bread in many areas of Hormozgan and parts of Bushehr province.

- Balotawa - is a dough spread over a pan placed over hot embers and mixed with eggs, sesame, and fish sauce; it is then heated with local oil or cheese. This may be the same type of "pizza" eaten by Darius the Great's soldiers in ancient wars

- Ranginak (Arabic: رنگینه/رنقينه, romanized: Rangeenah, Persian: رنگینک, romanized: Ranginak) is a type of sweet from the southern regions of Iran (Fars, Bushehr, Hormozgan, and Khuzestan) and in Arab states of the Persian Gulf,[92] made from dates or dried dates, flour, and cinnamon powder. In this local sweet, cinnamon and dates combine to create a delicious treat that can last up to a week in the refrigerator.

- Noun Regag (Arabic: خبز رقاق/خبز رگاگ, romanized: Knobz Regag, Persian: نان رگاگ, romanized: Nan Regag) also known as (Persian: لتک, romanized: litak) is common in Hormozgan, Laristan, and throughout the southern parts of Iran, as well as in Bahrain, Kuwait, and the UAE.

- Khanfaroosh, Khan (خان) meaning "House" and Foroosh (فروش) meaning "Selling," which translates to "Selling of the house" and its popular in both Arab states of the Persian Gulf (known as Arabic: خنفروش, romanized: Khanfaroosh),[93][94] and Southern Iran, It has "Achum/Acham" roots in southern Iran (particularly Hormozgan province).[95][96]

- Pishoo (Persian: پیشو) made from rose water (golab) and agar.[59]

- Cham-Chamoo (Persian: چم چمو) is a sweet naan that is made similar to Qeshm Island version.[59]

- Kebab Kenjeh Lari (Persian: کباب کنجه لاری) is one of the traditional and popular dishes in the city of Lar and the southern regions of Iran. This kebab is made from chunks of meat (usually lamb or beef) that are marinated in a mixture of yogurt, onion, saffron, lemon juice, and various spices, then skewered and grilled. Kebab Kenjeh Lari is known for its unique and delicious flavor and is typically served with either bread or rice.[97]

- Balaleet (Arabic: بلاليط, Persian: بلاليت) – This nutritious dessert of is prepared in Bahrain, Kuwait, the UAE, Hormozgan, and Bandar Abbas and other parts of Southern Iran. Balaleet is made from macaroni, sugar or date syrup, cardamom, rose water, saffron, and oil. It is traditionally served as a breakfast dish. This dessert is also popular in some other southern cities of Iran.

Khonj cuisine

Kashk o Bademjan, Miyeh, Meheh Roghan, Khoresh Gousht, Damikht, Polow Barj, Kideh, Reshk, Omeh, Awpiya, Ilim, Kleh Sar, Khak, Bi Pakh, Cheshgadeh, Doogh, Dowlat, Khazak Bad, Lchavo, Jarjat, Ardeh, Pashmak.[7]: 25

Qeshm cuisine

Mofalek, Kelmbarankineh Bantoolech, Doogh, Mast Haosorakh, Miyaveh May Brashtahkuli Khaskpoduni Ba Kuli, Poduni Ba Pao Rahoduni Bakashkh, Kashkh Khaskh, Mandah, Sorjosh Dadeh, Nan Tamshinan Dasti, Nan Liheh, Nan Khomeri, Nan Rakhteh, Nan Krosi, Nan Shekri (Setayari), Chinkal, Halva Narkil, Halva Turk, Halvashooli Berenj Dishobereng Sheleh, Hard Berenj.[7]

Other cuisine

Other foods are similar to national Iranian cuisine, which are shared among the majority of ethnic groups in Iran, such Chello Kabab (Persian: چلوکباب), Ash Reshteh (also known as Sholleh), desserts like Faloodeh (Persian: فالوده), Bastani (Iranian Ice cream), and even Afghan dishes like Shabat Pollow.

Traditional clothes

Women's Bandari variant

Men (regular class) outfit variant

Women's Evazi "Rakht Goshad" worn in marriage ceremonnies

Traditional Achomi clothes

The Khoodmoonis have a varied range of traditional clothes; the higher class men have their own outfits,[7]: 173 and the regular class outfit (presented in Shmd Lawry; شمد لاوری film).[98][7]: 173–174 [99]

The outfits are similar to Arab and Indian outfits in the Bandars (ports),[7]: 175 with southern variants identical to Zoroastrian outfits.[7]: 176

Women have what is known as "Rakht Goshad" in Evaz[100] with Bastaki,[101] Khonji, Lamerdi, Galedarie and Bandari variants.[100][7]: 174–177 [99]

Nowroz

The Khodmoonis are mostly devout people, and they celebrate the two Islamic Eids—Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha.[7]: 6 This sets them somewhat apart from other peoples in Iran, who celebrate the ancient Persian festivals due to the emergence of the national movement in Iran after Islam as a natural reaction to Arabization policies.[7]: 6 However, the Achomis/Khodmoonis were not significantly influenced by this movement and remained adherent to Islamic traditions. Yet, they cherish Persian heritage and its festivals, such as Nowruz, in their poetry, though they only celebrate it within a limited scope.[7]: 6 The Achomis/Khodmoonis have a rich tradition of poetry and songs related to spring season (Persian: موسم بهار, romanized: mawsem-e-bahar) – Nowruz,[102][103][104] which includes music too.[105][106][107]

From the poetry of Seyed Mohammad Seyed Ibrahim Dehtali, who died in 1344 AH, found in the book Bet va Deirashna (Persian: بت وديرآشنا), edited by Seyed Kamel:[7]

شِوُی درفصل نیسان .... کَمُی هُنسون ز باران

زمین دِن سبز وخرم .... زگلهای بهاران

دمامدم بوی شَبَمبو .... آهُند از دشت وهامون

گهی دِن ماه پیدا .... گهی در ابر وپنهان

On one of the spring nights... a light rain fell,

And the green lands... rejoiced with the flowers of spring.

The fragrances of wildflowers spread... coming from Dasht (the wilderness) and Hamon (desert).

At times, the moon appeared bright... and at times, it hid behind the clouds.

— Seyed Kamel, Seyed Mohammad Seyed Ibrahim Dehtali, Bet va Deirashna (Persian: بت وديرآشنا)

Local Games

- Khonj: Lwetkibelkhtar, Haft Sang, Khorpa, Sk Skala Belandi, Nader Bazi, Leher, Kase Pas Kun, Kab Bazi, Tira Gal, Gut Bazi, Kargam Be Hawa, Azad Bazi, Dar Chulk, Khormasho, Dar O Sop, Darbazi, Khorsho, Kai Kai, Til Ameh, Khat Khat, Panj Sank Ya Rokh, Yer Shesh Duneh, Beshkel Kol, Belm Petsk, Wast Wast, Allah Bedeh Baroon, Khooneh Khoda, Gap, Do Bel Bro, Bel Bel Jonam Bel, Charkhoneh, Shakhani Daraz, Mo Karkam Te Kalleh Aznam, Alla Kalang, Bel Wa Chak, To Zar Mo Zar, Lat Pas Pa, Khorkeh Tart o Shiri, Khor Sooz, Kai Ko, Asiyo Jalmep, Fandak, Mach o Feel.[7]: 25

- Qeshm: Kelmcha, Ramaza, Dar, Sawariya, Dartupa, Haft Senka, Charkhabaz Dar Magharahhul Wulat, Tilia, Dibia, Salam Salama, Wastarchomurokhta, Korkomochartak Abafam Hasile Bam.[7]

Local Beliefs

- Green flags: Some local beliefs in the region include the tradition of raising green flags when someone returns from Hajj or military service.[7]: 178

- Wednesday visits: Some people also have a custom of visiting on Wednesdays.[7]: 178

- Perfuming toys: There is a belief that it is necessary to perfume children's toys to ward off the evil eye.[7]: 178

- Mirrors in the wedding room: In the south, during wedding celebrations, the custom of the "hajlah" (a colorful wedding room decorated with mirrors) is common. This tradition is shared among the Persian Gulf countries, southern Iran, and parts of India.[7]: 178

- Baba Nowroz: Among the Achomi people of Khonj County in the Larestan region of Fars Province, there is a traditional figure known as Bā’ā Nowrez (Baba Nowruz). According to local belief, he visits households on the night before the new year while residents are asleep. On this night, families prepare their finest foods and leave them out for Bā’ā Nowrez. If he approves of the offerings, he is believed to bless the household with prosperity for the coming year. In addition, people wear green clothing, apply henna to their hands and heads, and ensure they are clean and perfumed before going to bed. This is intended to please Bā’ā Nowrez, so that their year will be as "green and fragrant" as their appearance. Conversely, failure to observe these customs is thought to anger Bā’ā Nowrez, who may then "twist their year," bringing misfortune, impurity, or scarcity.[citation needed]

Qalyoon/Giddu

The tobacco-only hookah made of pottery, known as Qalyoon in Persian, and referred to as Giddu or Ga-do (in Gulf Arabic dialects), both terms used simultaneously in the Arab Gulf states depending on the language being spoken, is an inseparable part of classic Persian and Iranian women's identity which has found its way to the Arab Gulf states among Achomi/Khodmooni women, and men.[citation needed]

Remove ads

In Pop culture

Summarize

Perspective

In the popular Achomi song "Dokht Qatari" (Qatari Girl) the song references buying a chador from Bander Abbas,[108] likely referring to Achomi people of Bander Abbas and Hormozgan in Qatar, the Achomi people of Bandar Abbas use "Khash" instead of "Khoob" (Persian);[109] meaning "good" and "Dokht" instead of "Dokhtar" (Persian) meaning "Girl" as well as "Chuk" (or "Pus") instead of "Pesar" (boy in Persian) as in Sahar's Bander Abbasi song.[110]

Emirati actress Huda Al-Khatib who herself is of Achomi ancestry has appeared in the Kuwaiti TV comedy drama serial "Al-Da'la" (الدعلة) where she speaks broken Arabic, and mixes it with Persian/Achomi, she brings up "bringing her giddu (گِدو; old traditional Iranian hookah) to fix her mood she is shown raging out in Achomi and Persian,[111][112] the show has a full scene in the 24th Episode in which the character she plays is shown learning the Arabic language and sings the Laristani/Achomi/Khudmuni/Bastaki song of Yousif Hadi Bastaki "Ghalyon ma teshn, ghori ma chai, yar nazanin, jaye to khali" (My hookah has no fire, my teapot has no tea, my beloved, your place is empty),[113] likely referencing the Achomi migrants' cultural identity and their challenges in adapting to Arabic-speaking environments, while also highlighting their efforts to preserve their linguistic and musical heritage despite assimilation pressures.

Historical Heritage

Summarize

Perspective

Khonj

The Shrine of Sheikh Afifuddin, The Lighthouse of Daniyal, The Grand Mosque of Kofeh Lake, The Shrine of Haj Sheikh Mohammad Abunajm, The Tomb of Kaka Raldin, Kohpayeh Park, Medina Park, Jahreh Cemetery Hill, Qara Aqaj Canal and the Seljuq era Ibrahim Dam, Nark Strait, Bar Bara o Bala, Al-Miyah Ahara (Alchaksama), Awnar, Bikhuyah Strait, Charkho Khonj, Bar Chel Gazi, Khan Baghi between Kaz Youz and Baghan, Rocks and Historic Khonj Troops from Different Eras, Koluqi Castle, Magellan Castle, Khelvat Castle, Shahnashin Castle, Senk Farsh Road from the Final Era, Talah Tavangran from the Sassanian Era, Mahmal Castle, Chireh Ghar, Bikhuyah Sadeh, Maz Qanats, Adkhama Nal Kuri Talah Shahmakh in the village of Jenkio (Mako Road to Khonj), The Big Talah near the village of Baghan and Haftwan Road.[7]: 25

Qeshm

Naderi Castle, Portuguese Castle, Water Reservoirs, Dome-shaped Dome, Historical Cemetery dating back to over a thousand years, Hormuz Castle, Old Laft, Koyal Khan or Hall for Hospitality, Church.[7]

Ancient Pre-Islamic Sites:

Mithraic Rock Remains (Izadmehr Anahita), Water Reservoirs of Laft from Pre-Islamic Eras, Laft Port and Harbor, Khorbas Water Reservoirs, Khorbas Ruins, Adkhamah Khorbas, Souq, Talah Kolgan, Sadda Tal Balaw Pipasht.[7]

In the countries around the Persian Gulf

The Badgir (wind-catcher): A style of traditional old architecture, which is found in most regions of Iran in various forms, such as in Kerman, Fars, Mazandaran, and Khorasan.[7]: 178 The Achomis/Khodmoonis are said to have brought the wind-catchers (badgirs), to the GCC Countries.[13][116][8]

- Al Bastakiya, Dubai

- Muharraq, Bahrain

- Souq Waqif, Doha, Qatar

- Bahrain

- Qasr al-Hosn, Abu Dhabi, AE

- Bastakiya: Al-Bastakiya is a neighbourhood in the eastern part of Dubai, established around the year 1308 AH / 1890 CE after the migration of Bastaki traders to the area. It is located along the Dubai Creek, approximately 300 meters long and 100 meters wide. The Bastakiya neighborhood is famous for its wind towers, intricately carved wooden doors, beautiful stucco work, and its reputation as a major tourist attraction and a place for official meetings in Dubai. When the Achomis/Khodmoonis/Larestanis arrived in Dubai they named this area Al-Bastakiya, after their own homeland.[8]

- Bahrain: The wind tower of "Isa bin Ali's House" in Muharraq, Bahrain, is an architectural building constructed by the Ajam (Achomis/Khodmoonis) of Bahrain.[13][116] Additionally, the first hotel in Bahrain known as "Bahrain Hotel" was opened by an Khodmooni man named "Abdul Noor Al Bastaki" which began construction in the 1920s and officially opened in 1950 and is set to receive renewal.[117][118]

Remove ads

Notable people

- Jalal al-Din Iradj, considered first Lari prince to convert to Islam.

- Fath Ali Khan Gerashi, first ruler of the Dehbashi family which ruled Larestan for a century up until Reza Shah.

- Rostam Khan Gerashi, second ruler of the Dehbashi family and son of Fath Ali Khan.

- Mohammad Jafar Khan (Sheyda Gerashi), third ruler of Larestan during the Dehbashi family reign.

- Mohammad Taqi Khan Bastaki, ruler of Bastak and Jahangiriyeh.

- Mohammad Reza Khan Bastaki, (Born: Mohammad Reza Khan ibn Mohammad Taqi Abbasi Hashemi 1880–1904), nicknamed "The Power of the Mamluks" (سُطْوَةُ المَمالِك), was a ruler of Bastak and Jahangirah, the son and successor of Mohammed Taqi Khan.

- Mohammad Azam Khan Bastaki, (Born: Mohammad Azam Khan Mohammad Reza Khan Bani Abbasian, 1906 - 1969) was the last Khan or ruler of Bastak and Jahangir after the khanate had lasted for 294 years.

- Ahmed Sultan from the Sultanies Band.

- Lotf Ali Khonji (born 1988) is an Iranian writer, translator, linguist, and journalist. He was born in 1938 in Bahrain. His father, Mohammad Amin Khonji, was a lover of the promotion of Iranian culture in Bahrain and one of the founders of the Iranian School in Bahrain. He is also a researcher in the Laristani/Achomi language.

- Arvin Bastaki (آروین بستکی), Iranian-born Emirati-Achomi singer who sings in Achomi.

- Ahmed Lari (احمد لاري), Member of National Assembly of Kuwait.

- Huda Al-Khatib (هدى الخطيب), Emirati-Achomi actress.[111][112]

- Amir Hossein Khonji, Historian and author of Iranian history, Islamologist, Poet, Linguist.

- Ahmed Eghtedari, Iranian-Achomi educator, scholar, author, writer and historian.

- Dr. Ibtesam Al-Bastaki, director of the Dubai Health Authority.

- Sonya Janahi, head of ILGO Bahrain.

- Ibtihal Al-Khatib (Arabic: ابتهال الخطيب), Kuwaiti academic, journalist, and prominent advocate of secular liberal values in Middle Eastern societies.

- Fatema Hameed Gerashi (Arabic: فاطمة حميد كراشي) - Bahraini swimmer

- Zainab Al Askari (Arabic: زينب العسكري) - Bahraini author and actress, Khodmooni with roots in Gerash.

- Khaled Janahi (Arabic: خالد جناحي) - Chairman of Vision 3, Member of Bahrain Economic Development Board and former partner at Pricewaterhouse Coopers. Sunni background.

- Khadja Al-Bastaki (خديجة البستكي), Senior Vice President of Dubai Design Destrict.

- Eman Aseery (Arabic: ايمان اسيري), Bahraini Poet.

- Hossein Asiri (حسين اسيري), Bahraini Achomi singer who sings in Bahraini Arabic, Farsi and Achomi.[119][120]

- Musa Al-Ansari (موسى الأنصاري), Secretary General of the Al-Ikha'a Association.[121]

- Mohammed Hassan Janahi, member of Bahraini parliament.[122]

- Mohamed Yousif Al-Maarafi, member of Bahraini parliament.[122]

- Hamid Khonji, Professor and member of the Central Committee of the Progressive Forum.

- Amal Al-Awadhi, Kuwaiti actress and model.

- Moein Al-Bastaki: Emirati presenter and trick magician of Achomi ancestry.

- Suhail Galadari: Emirati businessman of Huwala ancestry.

- Abdul Rahim Galadari: Emirati businessman of Huwala ancestry.

- Abdul Latif Galadari: Emirati businessman of Huwala ancestry.

- Majed Al-Abbasi: political activist in humans rights of religious & regional minorities, historian, iranologist, and journalist of Bander Abbasi Achomi/Khodmooni roots.[123]

Remove ads

See also

References

Notes

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads