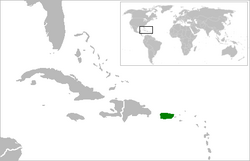

LGBTQ rights in Puerto Rico

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Puerto Rico have most of the same protections and rights as non-LGBT individuals. Public discussion and debate about sexual orientation and gender identity issues has increased, and some legal changes have been made. Supporters and opponents of legislation protecting the rights of LGBT persons can be found in both of the major political parties. Public opposition still exists due, in large part, to the strong influence of the Roman Catholic Church, as well as socially conservative Protestants. Puerto Rico has a great influence on the legal rights of LGBT citizens. Same-sex marriage has been legal in the commonwealth since July 2015, after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges that same-sex marriage bans are unconstitutional.

LGBTQ rights in Puerto Rico | |

|---|---|

| |

| Legal Status | Legal since 2003; codified in 2006 |

| Gender identity | Transgender people are legally allowed to change their gender |

| Military | Sexual orientation: Yes

Gender identity: Yes Transvestism: No Intersex status: No |

| Discrimination protections | As of June 2020, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity was removed from the new civil code of Puerto Rico - enacted with a signature from the Governor of Puerto Rico Wanda Vázquez Garced.[1] |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Same-sex marriage since 2015[2] |

| Adoption | Full adoption rights since 2015 |

Law regarding same-sex sexual activity

In 2002, the Puerto Rico Supreme Court ruled that the commonwealth's ban on sodomy was constitutional.[3] The next year, however, the U.S. Supreme Court declared unconstitutional all state and territorial statutes penalizing consensual sodomy, when limited to noncommercial acts between consenting adults in private, in Lawrence v. Texas. Puerto Rico modified its Penal Code in 2004 to reflect the decision and remove private, non-commercial sexual activity between consenting adults from its sodomy statute.[4]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

Summarize

Perspective

Legal restrictions

On March 19, 1999, Governor Pedro Rosselló signed into law H.B. 1013, which defined marriage as "a civil contract whereby a man and a woman mutually agree to become husband and wife."[5]

In 2008, there was an unsuccessful attempt in the Legislative Assembly to submit a referendum to voters to amend Puerto Rico's Constitution to define marriage as a union between a man and a woman, and to ban same-sex marriages, civil unions and domestic partnership benefits.[6] Similar legislation failed in 2009.[7]

Conde-Vidal v. Garcia-Padilla

Two women residing in Puerto Rico, represented by Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, filed a complaint in the U.S. District Court of Puerto Rico on March 25, 2014, seeking recognition of their 2004 marriage in Massachusetts.[8] Four more couples joined as plaintiffs in June.[9]

Judge Juan Pérez-Giménez dismissed the lawsuit on October 21, 2014, ruling that the United States Supreme Court's ruling in Baker v. Nelson (1972) prevented him from considering the plaintiffs' arguments. He concluded that Puerto Rico's definition of marriage did not conflict with the U.S. Constitution.[10]

The plaintiffs appealed the decision to the First Circuit Court of Appeals. On March 20, 2015, Puerto Rico Secretary of Justice César Miranda and Governor Alejandro García Padilla announced they had determined that Puerto Rico's statute banning the licensing and recognition of same-sex marriage was legally indefensible.[11] They asked the Court of Appeals to reverse the district court.[12]

On April 14, 2015, the First Circuit suspended proceedings pending a ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court in similar same-sex marriage cases.[13]

Supreme Court decision

As soon as the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges on June 26, 2015, that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry, Governor Padilla signed an executive order requiring government agencies to comply with the ruling within 15 days,[14] and all parties to the Conde-Vidal lawsuit asked the First Circuit to overrule the district court as soon as possible.[15] The first same-sex couples began applying for marriage licenses on July 13, 2015.[2]

In June 2018, a bill removing the heterosexual definition of marriage in Puerto Rican law and instead substituting a gender-neutral definition was introduced to the Puerto Rican Legislative Assembly. The bill would also raise the age of marriage from 14 to 18.[16]

In June 2020, Governor Wanda Vasquez signed into law a new Civil Code which deleted the previous ban on same-sex marriage, making marriage gender neutral.[17]

Domestic partner benefits

In 2013, Governor Garcia Padilla signed an order extending health insurance coverage to the same-sex domestic partners of workers in the executive branch.[18]

Domestic violence

In 2013, Representatives Luis Vega Ramos, Carlos Vargas Ferrer and José Báez Rivera introduced House Bill 488 to extend domestic violence protections to all households, regardless of sexual orientation and gender identity.[19] The House passed the legislation on 24 May.[18] Governor Garcia Padilla signed the legislation into law on 29 May.[20]

Adoption and parenting

Summarize

Perspective

Following the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, Puerto Rico's Department of Family ordered agency workers to consider only the "best interests of the child without prejudice" in future adoption and foster home placements. Families headed by same-sex couples are also entitled to apply for benefits such as those offered to opposite-sex families. These policies were announced on July 13, 2015.[21][22] The first successful adoption order for a same-sex couple in Puerto Rico was approved by a Puerto Rican court on December 10, 2015.[23]

Prior to this directive, adoption of children by same-sex couples and stepchild adoption by same-sex partners was prohibited by Puerto Rican law. In February 2013, the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico, in a 5–4 decision, affirmed the practised ban on same-sex adoption in Puerto Rico. The court's majority opinion held that Puerto Rico's Constitution "does not prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation" and accepted arguments presented by the Legislative Assembly that the "traditional family, composed of a father, a mother, and their children best protected the well-being of minors."[24] In January 2018, Governor Ricardo Rosselló signed into law a bill which brought Puerto Rico's adoption laws in line with Obergefell v. Hodges. The law now explicitly allows all couples, same-sex or opposite-sex, married or unmarried, to apply to adopt.[25]

Discrimination protections

Summarize

Perspective

An anti-discrimination bill (House Bill 1725) was introduced on May 21, 2009 to the island's House of Representatives, and it was approved by a 43 to 6 vote on November 11, 2009.[26] House Bill 1725 would have amended existing Puerto Rican civil rights laws to forbid discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in the areas of employment, public transportation and public facilities, business transactions, and housing. The legislation addressed sexual orientation only, not gender identity. The bill was referred to Puerto Rico's Senate and first discussed on December 18, 2009. The Senate Committees for Labor & Human Resources, and for Civil Matters, were both reviewing the measure. However, the President of the Senate, Thomas Rivera Schatz, a vocal opponent of the legislation, stated in early April 2010 on the Senate floor that the legislation would not be approved by the Senate. The Senate held no hearings and took no action.[27] At the same time, Governor Luis Fortuño, a member of the island's New Progressive Party and affiliated with the mainland Republican Party indicated that any discrimination law needs to state exemptions for organizations that object to homosexuality on the grounds of beliefs.

In 2013, Senator Ramón Luis Nieves introduced Senate Bill 238 to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. It acquired 14 co-sponsors, assuring its passage.[28] The Senate approved the legislation 15 to 11. By the time it passed by the House on a vote of 29 to 22 on 24 May, it had been amended to apply only to employment discrimination.[18] After final action by the Senate, Governor Garcia Padilla signed the legislation into law on 29 May.[20]

In 2017, the Puerto Rican Legislative Assembly approved a religious freedom bill, which would have authorized public businesses to legally discriminate against LGBT people. Governor Ricardo Rosselló vetoed the bill in February 2018.[29] On 11 June 2019, the Puerto Rico House of Representatives voted to approve a new religious freedom bill, amid outcry and protests.[30] On 13 June 2019, Rosselló asked lawmakers to withdraw the bill.[31][32][33][34]

Hate crime law

In 2002, Puerto Rico amended its hate crime statutes to include sexual orientation and gender identity as protected characteristics.[35] Puerto Rico is also covered by U.S. federal law, notably the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act.

2020 was the first year anyone in Puerto Rico was charged with a hate crime. Sean Díaz de León and Juan Pagán Bonilla were charged under the Hate crime law after Bonilla's confession, in which he stated he and Díaz de León murdered two transgender women on 22 April 2020.[36]

Gender identity and expression

Summarize

Perspective

Until 2018, Puerto Rican law forbade transgender people from changing their legal gender on their birth certificates. There had been unsuccessful legislative proposals to repeal this law.[37]

In April 2017, Lambda Legal filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of four transgender Puerto Ricans, challenging the law. They argued that denying transgender Puerto Ricans the ability to obtain accurate birth certificates violates the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses of the U.S. Constitution: "Puerto Rico categorically prohibits changes to the gender marker on birth certificates, even for those whose birth certificate does not match who they are. This policy has no rational justification in law or practice. In fact, government officials in Puerto Rico know this, as they, appropriately, allow transgender individuals to correct the gender marker on their drivers' licenses. Puerto Rico's birth certificate policy is at odds with the Federal Government's policies, with 46 out of the 50 states in the United States and the District of Columbia, and with common sense."[38]

In early April 2018, a federal judge struck down the law, ruling it unconstitutional. Local LGBT activists celebrated the judge's decision, with Lambda Legal labelling it "a tremendous victory for transgender people born in Puerto Rico". Shortly thereafter, a spokesperson for the Puerto Rican Government announced that the Government would not appeal the ruling.[39][40]

Since October 15, 2020, under the New Progressive Party (PNP) administration Puerto Rico Medicaid services explicitly covers transition, cost of care, hospital care treatment, sex reassignment surgery, hormone replacement therapy, and other gender related issues, etc.[41][42]

2021 State of emergency

In January 2021, it was reported that the Governor of Puerto Rico Pedro Pierluisi issued a state of emergency effective immediately - due to ongoing murders, assaults and rape of transgender individuals on Puerto Rico.[43]

Military service

The military defense of Puerto Rico has been the responsibility of the U.S. military, pursuant to the Treaty of Paris (1898) under which Spain ceded Puerto Rico to the United States. The U.S. military formerly had a "don't ask, don't tell" (DADT) policy regarding LGBTQ service members, and this presumably applied to the island's National Guard as well. The policy was repealed in December 2010 and ended on September 22, 2011.

Conversion therapy

Summarize

Perspective

Conversion therapy has a negative effect on the lives of LGBT people, and can lead to low self-esteem, depression and suicide ideation. There are a few known cases of minors being subjected to such practices in Puerto Rico. Between 2007 and 2008, a young gay man was repeatedly electrocuted as a part of a "treatment" to "cure" his homosexuality. He finally received an arrest warrant against his parents, who forced him to undergo the pseudoscientific practice.[44]

A bill to ban the use of conversion therapy on minors (Senate Bill 1000) was introduced to the Puerto Rican Senate on 17 May 2018, the International Day Against Homophobia.[44] The Senate approved this legislation 20 to 7, with two abstaining from voting, on March 7, 2019.[45] On March 18, 2019, the Puerto Rico House of Representatives blocked a vote on the bill, by refusing to vote on it or hold public hearings. The bill's author was Zoé Laboy from the New Progressive Party.[46] Nevertheless, House Speaker Gabriel Rodríguez Aguiló said in an interview that there was little evidence the practice was widely practiced in Puerto Rico. Some members of the House further thought that the definition of conversion therapy was "too broad" and could potentially include other types of rehabilitation therapy, such as for drug addiction.[47] Later that same day, Governor Ricardo Rosselló said he would issue an executive order banning conversion therapy for minors in the territory.[47] He issued such an executive order on March 27, taking effect immediately.[48] Territorial agencies were provided 90 days for promulgation of the new order.

In 2021 another Senate bill 184 to ban conversion therapies was voted down in the Commission of Community Incentives and Mental Health (Comisión de Iniciativas Comunitarias y Salud Mental).[49][50] Members of the New Progressive Party (PNP), Popular Democratic Party (PPD) and Joanne Rodríguez Veve of Proyecto Dignidad voted against the measure.[51][52] A similar bill was also introduced in the house and has been referred to various committees.[53]

Blood donation

Since April 2020, gay and bi men across the United States are allowed to donate blood - only after a 3 month deferral period.[54]

Political parties

Summarize

Perspective

Politicians from the Partido Popular Democrático and the Partido Nuevo Progresista de Puerto Rico, which are the island's two main political parties, include both supporters and opponents of LGBT rights. This face was most recently demonstrated by the House of Representatives vote on November 11, 2009, approving Bill 1725 (forbidding discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation). The bill passed by a vote of 43 to 6, with most representatives from both parties voting in favor. The six representatives voting against the bill were equally divided between both parties. Under the administration of Ricardo Rosselló the Governor's mansion for the first time in history was illuminated with rainbow colors in support of the LGBTQ community.[55]

The Puerto Rican Independence Party is a member of the Socialist International, and is on record as supporting full rights for LGBT citizens. Other smaller left wing pro-independence groups are also on record supporting LGBT rights. Yet, they have not proposed much legislation on advancing LGBTQ issues. In the Puerto Rican general election, 2012, all of the recently founded parties–Movimiento Unión Soberanista, the Puerto Ricans for Puerto Rico Party, and the Working People's Party of Puerto Rico–supported same-sex marriage and banning discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.[56]

On November 6, 2012, Popular Democratic Party candidate Pedro Peters Maldonado became the first openly gay politician elected to public office in the island's history, when he won a seat on San Juan's City Council.[57]

On September 24, 2020, New Progressive Party candidate Jorge Báez Pagán became the first openly gay member of the House of Representatives in the island's history.[58]

Public opinion

According to a Pew Research Center survey, conducted between November 7, 2013 and February 28, 2014, 33% of Puerto Ricans supported same-sex marriage, 55% were opposed.[59][60]

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Hate crime laws include sexual orientation and gender identity | |

| Same-sex marriage | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Gays, lesbians and bisexuals allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Transgender people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Transvestites allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Intersex people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians | |

| Automatic parenthood on birth certificates for children of same-sex couples | |

| Conversion therapy banned on minors | |

| LGBT anti-bullying law in schools and colleges | |

| Sex education in schools covers sexual orientation and gender identity | |

| Intersex minors protected from invasive surgical procedures | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Third gender option | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.