Alice Prin

French model and painter From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Alice Ernestine Prin (2 October 1901 – 29 April 1953), nicknamed the Queen of Montparnasse and often known as Kiki de Montparnasse, was a French model, chanteuse, memoirist and painter during the Jazz Age.[2] She flourished in, and helped define, the liberated culture of Paris in the so-called Années folles ("crazy years" in French). She became one of the most famous models of the 20th century and in the history of avant-garde art.[1][3]

Alice Prin | |

|---|---|

"Kiki" and Tsuguharu Foujita, Paris, 1926, by Iwata Nakayama | |

| Born | 2 October 1901 |

| Died | 29 April 1953 (aged 51) |

| Occupation(s) | Model, painter |

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Born as an illegitimate child in Châtillon-sur-Seine, Côte d'Or, Alice Prin had "a wretched childhood that could only lead to laughter or despair".[4][5] She was raised in abject poverty by her grandmother.[5] At age twelve, she was sent by train to live with her mother, a linotypist, in Paris in order to help earn an income for her family.[4][5] Harsh, degrading jobs followed, and she worked in printing shops, shoe factories and bakeries.[4][5] During this time, she began her lifelong joy of decorating herself.[4] She "would crumble a petal from her mother's fake geraniums to give color to her cheeks and was fired from a nasty job at a bakery because she darkened her eyebrows with burnt matchsticks".[4]

By the age of fourteen, Prin's "large and splendid body" had garnered the artistic and sexual attention of various Parisian denizens,[4] and she began surreptitiously posing nude for sculptors.[5] "It bothered me a little to take off my clothes," Prin wrote her in her memoirs, but "it was the custom".[5] Her decision to become a nude model created discord with her mother.[5] One day, her mother unexpectedly intruded into an artist's studio in a rage, denounced Prin as a shameless prostitute, and disowned her forever.[5]

Now without money or a roof over her head, the teenage Kiki determined to make her living exclusively by posing for artists.[5] As a beautiful dark-haired girl, she soon found herself in popular demand.[5] At the time, she had scant pubic hair, and when posing, she occasionally drew fake hair with a piece of charcoal.[5] As her fame grew, she became a local celebrity who symbolized the Montparnasse quarter's nonconformity and its rejection of the social norms of the petite bourgeoisie.[5]

Kiki de Montparnasse, 1928 bronze by Pablo Gargallo

Modeling career

Summarize

Perspective

Adopting a single name, "Kiki", Prin became a fixture of the Montparnasse social scene and a popular model, posing for dozens of artists, including Sanyu, Chaïm Soutine, Julien Mandel, Tsuguharu Foujita, Constant Detré, Francis Picabia, Jean Cocteau, Arno Breker, Alexander Calder, Per Krohg, Hermine David, Pablo Gargallo and Tono Salazar.[2] Moïse Kisling painted a portrait of Kiki titled Nu assis, one of his best known. In his 1976 book Memoirs of Montparnasse, Canadian poet John Glassco recalled that:

Her maquillage was a work of art in itself ...her mouth painted a deep scarlet that emphasized the sly erotic humor of its contours. Her face was beautiful from every angle, but I liked it best in full profile, when it had the lineal purity of a stuffed salmon.[4]

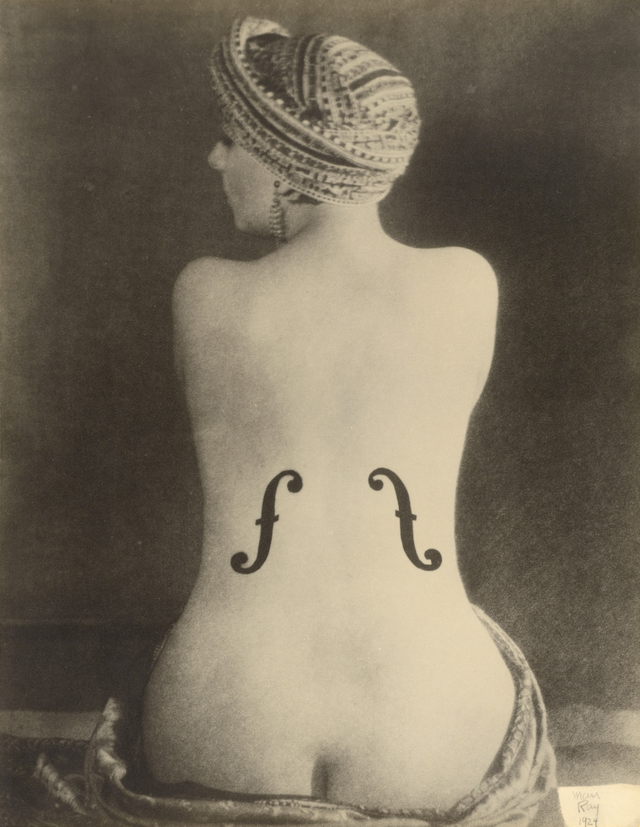

In Autumn 1921, Prin met the American visual artist Man Ray, and the two soon entered into a stormy eight-year relationship.[2][4] She lived with Man Ray in his studio on rue Campagne-Première until 1929 during which time he made hundreds of portraits of her.[2] She became his muse at the time and the subject of some of his best-known images, including the surrealist image Le Violon d'Ingres (Ingres' Violin) and Noire et blanche (Black and White).[1][6][7]

During their turbulent relationship, Man Ray labored obsessively on Prin's makeup and visual image.[8] He "took her many steps beyond the primitive charcoal eyebrow-pencil she used for makeup as a teenager."[9] Every night before going out together, he "meticulously applied her cosmetics and assisted in the choice of her clothes, creating a visual style that is as much a part of his oeuvre as any of his signed paintings".[8] Her makeup often varied in "the color, thickness, and angle according to his mood. Her heavy eyelids, next, might be done in copper one day and royal blue another, or else in silver and jade."[9]

By 1929, Prin had reached the zenith of her fame. She had appeared in nine short and frequently experimental films, including Fernand Léger's 1923 Dadaist work Ballet mécanique without any credit.[2] A symbol of bohemian and creative Paris and of the possibility of being a woman and finding an artistic place, she was elected the Queen of Montparnasse at age 28. Despite her local fame, she continued to live a hand-to-mouth existence. Even during difficult times, she maintained her positive attitude, saying "all I need is an onion, a bit of bread, and a bottle of red [wine]; and I will always find somebody to offer me that."[4]

Artwork and autobiography

Summarize

Perspective

A painter in her own right, Prin had a sold-out exhibition of her paintings in 1927 at the Galerie au Sacre du Printemps in Paris.[1] Signing her work with her chosen single name, Kiki, her drawings and paintings comprise portraits, self-portraits, social activities, fanciful animals and dreamy landscapes composed in a light, slightly uneven, expressionist style that is a reflection of her carefree manner and boundless optimism.[10]

In 1929, she published an autobiography titled Kiki's Memoirs, with Ernest Hemingway and Tsuguharu Foujita providing introductions.[1][11] In 1930, the book was translated by Samuel Putnam and published in Manhattan by Black Manikin Press, but it was immediately banned by the United States government. A copy of the first US edition was held in the section for banned books in the New York Public Library through the 1970s. However, the book had been reprinted under the title The Education of a Young Model throughout the 1950s and 1960s (e.g., a 1954 edition by Bridgehead has the Hemingway Introduction and photos and illustrations by Mahlon Blaine).

These editions were mainly put out by unscrupulous publisher Samuel Roth. Taking advantage that banned books did not receive copyright protection in the U.S., Roth put out a series of supposedly copyrighted editions (which never was registered with the Library of Congress) which altered the text and added illustrations—line drawings and photographs—which were not by Prin. After 1955, Roth appended an extra ten chapters falsely credited to Prin 23 years after the original book, including an invented visit to New York where she met with Roth himself.[12] None of this was true.[12] The original autobiography finally saw a new translation and publication in 1996.[12]

For a few years during the 1930s, Prin owned the Montparnasse cabaret L'Oasis, which was later renamed Chez Kiki.[2] Her music hall performances in black hose and garters included crowd-pleasing risqué songs, which were uninhibited, yet inoffensive. She later departed Paris to avoid the occupying German army during World War II, which entered the city in June 1940. She did not return to live in the city immediately after the war.

Death and legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Prin died at age 51 on 29 April 1953 after collapsing outside her flat in Montparnasse, apparently of complications of alcoholism or drug dependence.[4] At the time of her death, she weighed 175 pounds (79 kg).[13] A large crowd of artists and admirers attended her Paris funeral and followed the procession to her interment in the Cimetière parisien de Thiais. Her tomb identifies her as: "Kiki, 1901–1953, singer, actress, painter, Queen of Montparnasse".[14]

Life magazine featured a three-page obituary of Prin in its 29 June 1953 edition, concluding with a memory from one of her friends who said: "We laughed, my God how we laughed."[4] Tsuguharu Foujita remarked that, with Kiki's death, the glorious days of Montparnasse were buried forever.

Long after her death, Prin remains the embodiment of the outspokenness, audacity and creativity that marked the interwar period of life in Montparnasse. She represents a strong artistic force in her own right as a woman.[1] In 1989, biographers Billy Klüver and Julie Martin called her "one of the century's first truly independent women".[15] In her honor, a daylily has been named Kiki de Montparnasse.

On 14 May 2022, Le Violon d'Ingres, which depicts Prin's back overlaid with a violin's f-holes, sold for $12.4 million, setting a record as the most expensive photograph ever sold at auction.[1][16]

Gallery

- Kiki de Montparnasse by Julien Mandel

- c. 1920[17]

- Postcard, c. 1920

Filmography

- 1923: L'Inhumaine by Marcel L'Herbier

- 1923: Le Retour à la Raison by Man Ray, short film

- 1923: Ballet Mécanique by Fernand Léger, short film

- 1923: Entr'acte by René Clair, short film

- 1923: La Galerie des monstres by Jaque Catelain

- 1926: Emak-Bakia by Man Ray, short film

- 1928: L'Étoile de mer by Man Ray

- 1928: Paris express or Souvenirs de Paris by Pierre Prévert and Marcel Duhamel, short film

- 1930: Le Capitaine jaune by Anders Wilhelm Sandberg

- 1933: Cette vieille canaille by Anatole Litvak

Kiki's Memoirs

- Anon. (n.d.). "The Classical Poses of Julian Mandel". Tallulahs Gallery. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- Prin, Alice (1928). Les souvenirs de Kiki (in French). Preface by Tsuguharu Foujita. Introduction by Ernest Hemingway. Illustrations by Man Ray. Paris: Henri Broca. OCLC 459619230.

- Prin, Alice (1930). Kiki's Memoirs. Translated by Putnam, Samuel. Preface by Tsuguharu Foujita. Introduction by Ernest Hemingway. Illustrations by Man Ray, Foujita, et al. Paris: Edward W. Titus (Black Manikin Press). OCLC 463955972.

- Prin, Alice (1950). The Education of a French Model: The Loves, Cares, Cartoons, and Caricatures of Alice Prin. Translated by Putnam, Samuel. Introduction by Ernest Hemingway. Boar's Head. OCLC 1224376087.

- Kiki's Memoirs (1996) translation by Samuel Putnam (original ed. published by J. Corti, Paris) Kiki's memoirs. Hopewell, New Jersey: The Ecco Press. 1996. ISBN 0880014962.

- Souvenirs, introduction by Ernest Hemingway and Tsuguharu Foujita, foreword and notes by Billy Klüver and Julie Martin, translation by Dominique Lablanche, Hazan, 1999.

- Souvenirs retrouvés, preface by Serge Plantureux, José Corti, 2005.

- Kiki's Memoirs (2009) [Recuerdos recobrados] translation by José Pazó Espinosa (in Spanish – published by Nocturna)

- Kiki Souvenirs, 1929 (2005) translation by N. Semoniff (in Russian – published by Salamandra P.V.V., 2011)

- Kiki's Memoirs, 1930 (2006) translation by N. Semoniff (in Russian – published by Salamandra P.V.V., 2011)

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.