Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

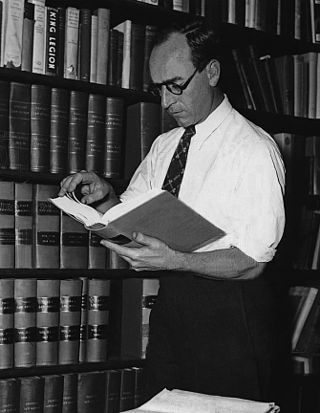

Karl Llewellyn

American legal scholar From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Karl Nickerson Llewellyn (May 22, 1893 – February 13, 1962) was an American jurisprudential scholar associated with the school of legal realism. The Journal of Legal Studies has identified Llewellyn as one of the twenty most cited American legal scholars of the 20th century.[1]

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Karl Llewellyn was born on May 22, 1893, in Seattle but grew up in Brooklyn. He was the son of William Henry Llewellyn, a businessman of Welsh ancestry, and Janet George, a passionate suffragette and prohibitionist of Congregationalist conviction.[2] He attended Boys High School. At the age of sixteen he was sent to study in Germany, at the Realgymnasium of Schwerin, where he spent three years and passed his Abitur (school-leaving examination) in the spring of 1911; he learned to speak an excellent German and was able later in life to publish in that language.[2][3] After having attended the University of Lausanne for a brief time, in September 1911 he entered Yale College and in 1915 Yale Law School, earning an LL.B. in 1918 and a J.D. in 1920. He was elected to the editorial board of the Yale Law Journal in 1916 and graduated top of his class in 1918 magna cum laude.[2][4] At Yale he got acquainted with two prominent law professors and key figures of the incipient legal realism movement, Arthur L. Corbin and Wesley N. Hohfeld, whose influence on him was profound.[5]

Llewellyn was studying abroad at the Sorbonne in Paris when World War I broke out in 1914. He was sympathetic to the German cause and traveled to Germany to enlist in the German army, but his refusal to renounce his American citizenship made him ineligible. He was allowed to fight with the 78th Prussian Infantry Regiment and was injured at the First Battle of Ypres.[6] For his actions, he was promoted to sergeant and decorated with the Iron Cross, 2nd class. After spending ten weeks in a German hospital at Nürtingen and having his petition to enlist without swearing allegiance to Germany turned down, Llewellyn returned to the United States and to his studies at Yale in March 1915. After the United States entered the war, Llewellyn attempted to enlist in the United States Army but was rejected because he had fought on the German side.[7]

He joined the Columbia Law School faculty in 1925, where he remained until 1951, when he was appointed professor of the University of Chicago Law School. While at Columbia, Llewellyn became one of the major legal scholars of his day. He was a major proponent of legal realism. He also served as principal drafter of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC).

Llewellyn married his former student Soia Mentschikoff, who had become a law professor and was also a UCC drafter. She also accepted a teaching post at Chicago and later became dean of University of Miami School of Law.[8]

Llewellyn died in Chicago of a heart attack on February 13, 1962.

Remove ads

Legal realism

Compared with traditional jurisprudence, known as legal formalism, Llewellyn and the legal realists proposed that the facts and outcomes of specific cases composed the law, rather than logical reasoning from legal rules. They argued that law is not a deductive science. Llewellyn epitomized the realist view when he wrote that what judges, lawyers, and law enforcement officers "do about disputes is, to my mind, the law itself" (Bramble Bush, p. 3).

As one of the founders of the U.S. legal realism movement, he believed that the law is little more than putty in the hands of a judge who is able to shape the outcome of a case based on personal biases.[9]

Remove ads

Publications

- 1930: The Bramble Bush: On Our Law and Its Study (1930), written especially for first-year law students. A new edition, edited and with an introduction by Steven Sheppard, was published in 2009 by Oxford University Press.

- 1941: The Cheyenne Way (with E. Adamson Hoebel) (1941), University of Oklahoma Press.

- 1960: The Common Law Tradition—Deciding Appeals (1960), Little, Brown and Company.

- 1962: Jurisprudence: Realism in Theory and Practice (1962).

- 1989: The Case Law System in America, edited and with an introduction by Paul Gewirtz, University of Chicago Press (revised text of lectures delivered in German at the University of Leipzig in 1928, originally published in German in 1933)[10]

- 2011: The Theory of Rules, edited and with an introduction by Frederick Schauer, University of Chicago Press (a lost treatise rediscovered decades after Llewellyn's death)

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads