Königliches Hoftheater Dresden

German opera house From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

German opera house From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

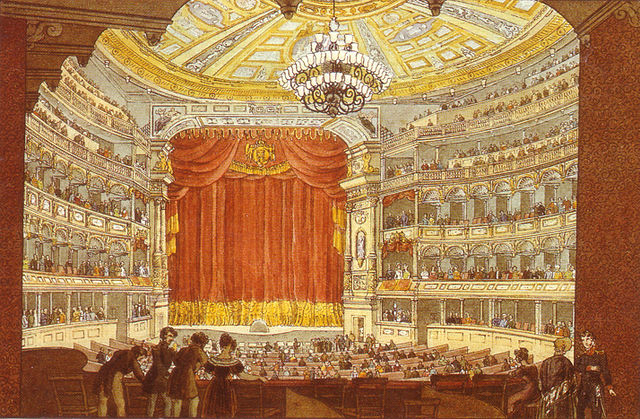

The Königliches Hoftheater (Royal Court Theatre) in Dresden, Saxony, was a theatre for opera and drama in the royal seat of the Kingdom of Saxony from 1841 and 1869, designed by Gottfried Semper. It was the predecessor of today's Semperoper, and is therefore sometimes called Altes Hoftheater (Old Court Theatre).

From 1838 to 1841, the architect Gottfried Semper built a representative opera house, which replaced the previous Morettisches Opernhaus. He took the forum plan devised by Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann as the basis for his well thought-out urban planning solution. The opening took place on 12 April 1841 with Carl Maria von Weber's Jubelouvertüre and Goethe's Torquato Tasso.

The circular building in the forms of the Italian early Renaissance was praised as one of the most beautiful European theatres. Semper's first theatre building was considerably closer to the castle than his second opera house, which still exists today; the forerunner of today's Theaterplatz was laid out in front of the opera in 1840.

In the following years, Richard Wagner was Kapellmeister there, and gave the world premieres of several of his music dramas: Rienzi, Der fliegende Holländer and Tannhäuser, with singers including Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient and Joseph Tichatschek.

In 1838, the respected Dresden clockmaker Friedrich Gutkaes was commissioned to construct a clock that could be easily read from all seats. This clock from the Kunstuhrenfabrik Gutkaes is today one of the most historically significant of its kind.[1]

On 21 September 1869, the theatre building was completely destroyed in a fire due to carelessness during repair work. After the catastrophe, performances continued for a few years in an interim theatre, the so-called "Bretterbude". Meanwhile, Semper was working on new building plans for the second theatre, today's Semperoper.

The Dresden court councillor Wilhelm Lesky built his Villa estate in Kötzschenbroda on the remains of the burnt-down first Semper's Opera House as a picturesque arrangement of ruins. These spolias are no longer preserved today. In contrast, the so-called Rietschelgiebel, which can be seen today at the Burgtheater on the Ortenburg in Bautzen, has been preserved. This group of figures created by Ernst Rietschel with the title "Allegory of Tragedy" was originally installed on the north wall of the Dresden Court Theatre, but had no longer found a use when the opera house was rebuilt.

Important conductors worked at the Königliches Hoftheater:

Ida von Lüttichau, wife of the general director Wolf Adolf August von Lüttichau, reported in a letter:[2]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.