Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Jizya

Islamic tax on non-Muslims From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Jizya (Arabic: جِزْيَة, romanized: jizya), or jizyah,[1] is a type of taxation levied on non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law.[2] The Quran and hadiths mention jizya without specifying its rate or amount,[3] and the application of jizya varied in the course of Islamic history. However, scholars largely agree that early Muslim rulers adapted some of the existing systems of taxation and modified them according to Islamic religious law.[4][5][6][7][8]

Historically, the jizya tax has been understood in Islam as a fee for protection provided by the Muslim ruler to non-Muslims, for the exemption from military service for non-Muslims, for the permission to practice a non-Muslim faith with some communal autonomy in a Muslim state, and as material proof of the non-Muslims' allegiance to the Muslim state and its laws.[9][10][11] The majority of Muslim jurists required adult, free, sane males among the dhimma community to pay the jizya,[12] while exempting women, children, elders, handicapped, the ill, the insane, monks, hermits, slaves,[13][14][15][16][17] and musta'mins—non-Muslim foreigners who only temporarily reside in Muslim lands.[13][4] However, some jurists, such as Ibn Hazm, required that anyone who had reached puberty pay jizya.[18] Islamic Regimes allowed dhimmis to serve in Muslim armies. Those who chose to join military service were also exempted from payment;[2][14][19][20][21][22] some Muslim scholars claim that some Islamic rulers exempted those who could not afford to pay from the Jizya.[14][23][24]

Together with kharāj, a term that was sometimes used interchangeably with jizya,[25][26][27] taxes levied on non-Muslim subjects were among the main sources of revenues collected by some Islamic polities, such as the Ottoman Empire and Indian Muslim Sultanates.[28] Jizya rate was usually a fixed annual amount depending on the financial capability of the payer.[29] Sources comparing taxes levied on Muslims and jizya differ as to their relative burden depending on time, place, specific taxes under consideration, and other factors.[2][30][31]

The term appears in the Quran referring to a tax or tribute from People of the Book, specifically Jews and Christians. Followers of other religions like Zoroastrians and Hindus too were later integrated into the category of dhimmis and required to pay jizya. In the Indian subcontinent the practice stopped by the 18th century with Muslim rulers losing their kingdoms to the Maratha Empire and the British East India Company. It almost vanished during the 20th century with the disappearance of Islamic states and the spread of religious tolerance.[32] The tax is no longer imposed by nation states in the Islamic world,[33][34] although there are reported cases of organizations such as the Pakistani Taliban and ISIS attempting to revive the practice.[32][35][36]

Remove ads

Etymology and meaning

Summarize

Perspective

Commentators disagree on the definition and derivation of the word jizya. Ann Lambton writes that the origins of jizya are extremely complex, regarded by some jurists as "compensation paid by non-Muslims for being spared from death" and by others as "compensation for living in Muslim lands."[37]

According to Encyclopedia Iranica, the Arabic word jizya is most likely derived from Middle Persian gazītak, which denoted a tax levied on the lower classes of society in Sasanian Persia, from which the nobles, clergy, landowners (dehqāns), and scribes (or civil servants, dabirān) were exempted. Muslim Arab conquerors largely retained the taxation systems of the Sasanian and Byzantine empires they had conquered.[38]

Shakir's English translations of the Qur'an render jizya as 'tax', while Pickthall and Arberry translate it as "tribute". Yusuf Ali prefers to transliterate the term as jizyah. Yusuf Ali considered the root meaning of jizya to be "compensation,"[39][40] whereas Muhammad Asad considered it to be "satisfaction."[39]

Al-Raghib al-Isfahani (d. 1108), a classical Muslim lexicographer, writes that jizya is a "tax that is levied on Dhimmis, and it is so named because it is in return for the protection they are guaranteed."[41] He points out that derivatives of the word appear in some Qurʾānic verses as well, such as:[42]

- "Such is the reward (jazāʾ) of those who purify themselves" (Q 20:76)

- "While those who believed and did good deeds will have the best of rewards" (Q 18:88)

- "And the retribution for an evil act is an evil one like it, but whoever pardons and makes reconciliation – his reward is [due] from God" (Q 42:40)

- "And will reward them for what they patiently endured [with] a garden [in Paradise] and silk [garments]" (Q 76:12)

- "and be repaid only according to your deeds" (Q 37:39)

Muhammad Abdel-Haleem states that the term poll tax does not translate the Arabic word jizya, being also inaccurate in light of the exemptions granted to children, women, etc., unlike a poll tax, which by definition is levied on every individual (poll = head) regardless of gender, age, or ability to pay. He further adds that the root verb of jizya is j-z-y, which means 'to reward somebody for something', 'to pay what is due in return for something' and adds that it is in return for the protection of the Muslim state with all the accruing benefits and exemption from military service, and such taxes on Muslims as zakat.[43]

The historian al-Tabari and the hadith scholar al-Bayhaqi relate that some members of the Christian community asked ʿUmar ibn al-Khattab if they could refer to the jizya as sadaqah, literally 'charity', which he allowed.[30][44][45] Based on this historical event, the majority of jurists from Shāfiʿīs, Ḥanafīs and Ḥanbalīs state that it is lawful to take the jizya from ahl al-dhimmah by name of zakāt or ṣadaqah, meaning it is not necessary to call the tax that is taken from them by jizya, and also based on the known legal maxim that states, "consideration is granted to objectives and meanings and not to terms and specific wordings."[46]

According to Lane's Lexicon, jizya is the tax that is taken from the free non-Muslim subjects of an Islamic government, whereby they ratify the pact that ensures them protection.[47][48]

Michael G. Morony states that:[49]

[The emergence of] protected status and the definition of jizya as the poll tax on non-Muslim subjects appears to have been achieved only by the early eighth century. This came as a result of growing suspicions about the loyalty of the non-Muslim population during the second civil war and of the literalist interpretation of the Quran by pious Muslims.

Jane Dammen McAuliffe states that jizya, in early Islamic texts, was an annual tribute expected from non-Muslims, and not a poll tax.[50] Similarly, Thomas Walker Arnold writes that jizya originally denoted tribute of any type paid by the non-Muslim subjects of the Arab empire, but that it came later on to be used for the capitation-tax, "as the fiscal system of the new rulers became fixed."[51]

Arthur Stanley Tritton states that both jizya in west, and kharaj in the east Arabia meant 'tribute'. It was also called jawali in Jerusalem.[52][53] Shemesh says that Abu Yusuf, Abu Ubayd ibn al-Sallām, Qudama ibn Jaʿfar, Khatib, and Yahya ibn Adam used the terms Jizya, Kharaj, Ushr and Tasq as synonyms.[54]

The Arabic lexicographer Edward William Lane, after a careful analysis of the etymology of the term "Jizya", says: "The tax that is taken from the free non-Muslim subjects of a Muslim government whereby they ratify the compact that assures them protection, as though it were compensation for not being slain".[55]

Remove ads

Rationale

Summarize

Perspective

Payment for protection

According to Abou Al-Fadl and other scholars, classical Muslim jurists and scholars regard the jizya as a special payment collected from certain non-Muslims in return for the responsibility of protection fulfilled by Muslims against any type of aggression,[56][12][10][11][48][57][58][59][60] as well as for non-Muslims being exempt from military service,[12][61][10][11][20][39][43][62][63] and in exchange for the aid provided to poor dhimmis.[31] In a treaty made by Khalid with some towns in the neighborhood of Hirah, he writes: "If we protect you, then jizya is due to us; but if we do not, then it is not due."[64][65][66][67][68] Early Hanafi jurist Abu Yusuf writes:

'After Abu ʿUbaydah concluded a peace treaty with the people of Syria and had collected from them the jizya and the tax for agrarian land (kharāj), he was informed that the Romans were readying for battle against him and that the situation had become critical for him and the Muslims. Abu ʿUbaydah then wrote to the governors of the cities with whom pacts had been concluded that they must return the sums collected from jizya and kharāj and say to their subjects: "We return to you your money because we have been informed that troops are being raised against us. In our agreement you stipulated that we protect you, but we are unable to do so. Therefore, we now return to you what we have taken from you, and we will abide by the stipulation and what has been written down, if God grants us victory over them."'[69][70][71][72]

In accordance with this order, enormous sums were paid back out of the state treasury,[70] and the Christians called down blessings on the heads of the Muslims, saying, "May God give you rule over us again and make you victorious over the Romans; had it been they, they would not have given us back anything, but would have taken all that remained with us."[70][71] Similarly, during the time of the Crusades, Saladin returned the jizya to the Christians of Syria when he was compelled to retract from it.[73] The Christian tribe of al-Jurajima, in the neighborhood of Antioch, made peace with the Muslims, promising to be their allies and fight on their side in battle, on condition that they should not be called upon to pay jizya and should receive their proper share of the booty.[21][74] The orientalist Thomas Walker Arnold writes that even Muslims were made to pay a tax if they were exempted from military service, like non-Muslims.[75][76] Thus, the Shafi'i scholar al-Khaṭīb ash-Shirbīniy states: "Military service is not obligatory for non-Muslims – especially for dhimmis since they give jizya so that we protect and defend them, and not so that he defends us."[77] Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani states that there is a consensus amongst Islamic jurists that jizya is in exchange for military service.[78] In the case of war, jizya is seen as an option to end hostilities. According to Abu Kalam Azad, one of the main objectives of jizya was to facilitate a peaceful solution to hostility, since non-Muslims who engaged in fighting against Muslims were thereby given the option of making peace by agreeing to pay jizya. In this sense, jizya is seen as a means by which to legalize the cessation of war and military conflict with non-Muslims.[79] In a similar vein, Mahmud Shaltut states that "jizya was never intended as payment in return for one's life or retaining one's religion, it was intended as a symbol to signify yielding, an end of hostility and a participation in shouldering the burdens of the state."[80]

Other rationales

Modern scholars have also suggested other rationales for the Jizya, both in a historic context, and, among modern Islamist thinkers, as a justification for the use of Jizya in a modern context,[81][82] including:

- as a symbol of humiliation to remind dhimmis of their status as a conquered people and their subjection to Islamic laws[83]

- as a financial and political incentive for dhimmis to convert to Islam.[9][83] The Muslim jurist and theologian Fakhr al-Din al-Razi suggested in his interpretation of Q.9:29 that jizya is an incentive to convert. Taking it is not intended to preserve the existence of disbelief (kufr) in the world. Rather, he argues, jizya allows the non-Muslim to live amongst Muslims and take part in Islamic civilization in the hope that the non-Muslim will convert to Islam.[84]

- as a substantial source of revenue for at least some times and places (such as the Umayyad era) and as economically inconsequential in others.[85][86]

- Asma Afsaruddin also writes that around the end of the 8th century CE, "payment of the jizyah began to be conceptualized by a number of influential jurists as a marker of inferior socio-legal status for the non-Muslim", as "earlier tolerant attitudes toward non-Muslims began to harden".[1]

- Sayyid Qutb saw it as punishment for "polytheism".

- Modern Pakistani scholars have taking the stance of viewing the badge of humiliation or as a mercy for non-Muslims for the protection given to them by the Muslims.[a]

- Abdul Rahman Doi has interpreted it as a counterpart of the zakat tax paid by Muslims.[81]

- The 11th century jurist Ibn Hazm elaborates; "Allah has established the infidel's ownership of their property only for the institution of booty for Muslims".[87]

- Muslim Jurist Malik ibn Anas's al-Muwatta declares that "Zakat is imposed on the Muslims to purify them and to be given back to their poor, whereas jizya is imposed on the people of the Book to humble them (to show they are subjects of the state)."[88]

Remove ads

In the Qur'an

Summarize

Perspective

Jizya is sanctioned by the Qur'an based on the following verse:

qātilū-lladhīna lā yuʾminūna bi-llāhi wa-lā bi-l-yawmi-l-ākhir, wa-lā yuḥarrimūna mā ḥarrama-llāhu wa-rasūluh, wa-lā yadīnūna dīna'l-ḥaqq, ḥattā yu'ṭū-l-jizyata 'an yadin, wa-hum ṣāghirūn

Translation:

Fight those who believe not in God and in the Last Day, and who do not forbid what God and His Messenger have forbidden, and who follow not the Religion of Truth among those who were given the Book, till they pay the jizyah with a willing hand, being humbled.

1. "Fight those who believe not in God and the Last Day" (qātilū-lladhīna lā yuʾminūna bi-llāhi wa-lā bi-l-yawmi-l-ākhir).

Commenting on this verse, Muhammad Sa'id Ramadan al-Buti says:[91]

[T]he verse commands qitāl (قتال) and not qatl (قتل), and it is known that there is a big distinction between these two words ... For you say 'qataltu (قتلت) so-and-so' if you initiated the fighting, while you say 'qātaltu (قاتلت) him' if you resisted his effort to fight you by a reciprocal fight, or if you forestalled him in that so that he would not get at you unawares.

Muhammad Abdel-Haleem writes that there is nothing in the Qur'an to say that not believing in God and the Last Day is in itself grounds for fighting anyone.[92] Whereas Abū Ḥayyān states "they are so described because their way [of acting] is the way of those who do not believe in God,"[92] Ahmad Al-Maraghī comments:[93]

[F]ight those mentioned when the conditions which necessitate fighting are present, namely, aggression against you or your country, oppression and persecution against you on account of your faith, or threatening your safety and security, as was committed against you by the Byzantines, which was what led to Tabuk.

2. "Do not forbid what God and His Messenger have forbidden" (wa-lā yuḥarrimūna mā ḥarrama-llāhu wa-rasūluh).

The closest and most viable cause must relate to jizya, that is, unlawfully consuming what belongs to the Muslim state, which, al-Bayḍāwī explains, "it has been decided that they should give,"[92][94] since their own scriptures and prophets forbid breaking agreements and not paying what is due to others. His Messenger in this verse has been interpreted by exegetes as referring to Muḥammad or the People of the Book's own earlier messengers, Moses or Jesus. According to Abdel-Haleem, the latter must be the correct interpretation as it is already assumed that the People of the Book did not believe in Muḥammad or forbid what he forbade, so that they are condemned for not obeying their own prophet, who told them to honour their agreements.[92]

3. "Who do not embrace the true faith" or "behave according to the rule of justice" (wa-lā yadīnūna dīna'l-ḥaqq).

A number of translators have rendered the text as "those who do not embrace the true faith/follow the religion of truth" or some variation thereof.[citation needed] Muhammad Abdel-Haleem argues against this translation, preferring instead to render dīna'l-ḥaqq as 'rule of justice'.

The main meaning of the Arabic dāna is 'he obeyed', and one of the many meanings of dīn is 'behaviour' (al-sīra wa'l-ʿāda).[92] The famous Arabic lexicographer Fayrūzabādī (d. 817/1415), gives more than twelve meanings for the word dīn, placing the meaning 'worship of God, religion' lower in the list.[92][95] Al-Muʿjam al-wasīṭ gives the following definition: "'dāna' is to be in the habit of doing something good or bad; 'dāna bi- something' is to take it as a religion and worship God through it." Thus, when the verb dāna is used in the sense of 'to believe' or 'to practise a religion', it takes the preposition bi- after it (e.g. dāna bi'l-Islām) and this is the only usage in which the word means religion.[92][96] The jizya verse does not say lā yadīnūna bi-dīni'l-ḥaqq, but rather lā yadīnūna dīna'l-ḥaqq.[92] Abdel-Haleem thus concludes that the meaning that fits the jizya verse is thus 'those who do not follow the way of justice (al-ḥaqq)', i.e. by breaking their agreement and refusing to pay what is due.[92]

4. "Until they pay jizya with their own hands" (ḥattā yu'ṭū-l-jizyata 'an yadin).

Here ʿan yad (from/for/at hand), is interpreted by some to mean that they should pay directly, without intermediary and without delay. Others say that it refers to its reception by Muslims and means "generously" as in "with an open hand," since the taking of the jizya is a form of munificence that averted a state of conflict.[97] al-Ṭabarī gives only one explanation: that 'it means "from their hands to the hands of the receiver" just as we say "I spoke to him mouth to mouth", we also say, "I gave it to him hand to hand"'.[24] M.J. Kister understands 'an yad to be a reference to the "ability and sufficient means" of the dhimmi.[98] Similarly, Rashid Rida takes the word Yad in a metaphorical sense and relates the phrase to the financial ability of the person liable to pay jizya.[39]

5. "While they are subdued" (wa-hum ṣāghirūn).

Mark R. Cohen writes that 'while they are subdued' was interpreted by many to mean the "humiliated state of the non-Muslims".[99] According to Ziauddin Ahmed, in the view of the majority of Fuqahā (Islamic jurists), the jizya was levied on non-Muslims in order to humiliate them for their unbelief.[100] In contrast, Abdel-Haleem writes that this notion of humiliation runs contrary to verses such as, Do not dispute with the People of the Book except in the best manner (Q 29:46), and the Prophetic ḥadīth,[101] 'May God have mercy on the man who is liberal and easy-going (samḥ) when he buys, when he sells, and when he demands what is due to him'.[24] Al-Shafi'i, the founder of the Shafi'i school of law, wrote that a number of scholars explained this last expression to mean that "Islamic rulings are enforced on them."[102][103][104] This understanding is reiterated by the Hanbali jurist Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya, who interprets wa-hum ṣāghirūn as making all subjects of the state obey the law and, in the case of the People of the Book, pay the jizya.[61]

Remove ads

In the classical era

Summarize

Perspective

Liability and exemptions

Rules for liability and exemptions of jizya formulated by jurists in the early Abbasid period appear to have remained generally valid thereafter.[105][106]

Islamic jurists required adult, free, sane, able-bodied males of military age with no religious functions among the dhimma community to pay the jizya,[12] while exempting women, children, elders, handicapped, monks, hermits, the poor, the ill, the insane, slaves,[12][13][14][15][16] as well as musta'mins (non-Muslim foreigners who only temporarily reside in Muslim lands)[13] and converts to Islam.[37] Dhimmis who chose to join military service were exempted from payment.[2][14][19][21][22] If anyone could not afford this tax, they would not have to pay anything.[14][61][24] Sometimes a dhimmi was exempted from jizya if he rendered some valuable services to the state.[76]

The Hanafi scholar Abu Yusuf wrote, "slaves, women, children, the old, the sick, monks, hermits, the insane, the blind and the poor, were exempt from the tax"[107] and states that jizya should not be collected from those who have neither income nor any property, but survive by begging and from alms.[107] The Hanbali jurist al-Qāḍī Abū Yaʿlā states, "there is no jizya upon the poor, the old, and the chronically ill".[108] Historical reports tell of exemptions granted by the second caliph 'Umar to an old blind Jew and others like him.[12][109][110][111][112][113][114] The Maliki scholar Al-Qurtubi writes that, "there is a consensus amongst Islamic scholars that jizya is to be taken only from heads of free men past puberty, who are the ones fighting, but not from women, the children, the slaves, the insane, and the dying old."[115] The 13th century Shafi'i scholar Al-Nawawī wrote that a "woman, a hermaphrodite, a slave even when partially enfranchised, a minor and a lunatic are exempt from jizya."[116][117] The 14th century Hanbali scholar Ibn Qayyim wrote, "And there is no Jizya upon the aged, one suffering from chronic disease, the blind, and the patient who has no hope of recovery and has despaired of his health, even if they have enough."[118] Ibn Qayyim adds, referring to the four Sunni maddhabs: "There is no Jizya on the kids, women and the insane. This is the view of the four imams and their followers. Ibn Mundhir said, 'I do not know anyone to have differed with them.' Ibn Qudama said in al-Mughni, 'We do not know of any difference of opinion among the learned on this issue."[119] In contrast, the Shāfi'ī jurist Al-Nawawī wrote: "Our school insists upon the payment of the poll-tax by sickly persons, old men, even if decrepit, blind men, monks, workmen, and poor persons incapable of exercising a trade. As for people who seem to be insolvent at the end of the year, the sum of the poll tax remained as debt to their account until they should become solvent."[116][117] Abu Hanifa, in one of his opinions, and Abu Yusuf held that monks were subject to jizya if they worked.[120] Ibn Qayyim stated that the dhahir opinion of Ibn Hanbal is that peasants and cultivators were also exempted from jizya.[121]

Though jizya was mandated initially for People of the Book (Judaism, Christianity, Sabianism), it was extended by Islamic jurists to all non-Muslims.[122][123] Thus Muslim rulers in India, with the exception of Akbar, collected jizya from Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs under their rule.[124][not specific enough to verify][125][126] While early Islamic scholars like Abu Hanifa and Abu Yusuf stated that jizya should be imposed on all non-Muslims without distinction, some later and more extremist jurists do not permit jizya for idolators and instead only allowed the choice of conversion to avoid death.[127]

The sources of jizya and the practices varied significantly over Islamic history.[128][129] Shelomo Dov Goitein states that the exemptions for the indigent, the invalids and the old were no longer observed in the milieu reflected by the Cairo Geniza and were discarded even in theory by the Shāfi'ī jurists who were influential in Egypt at the time.[130] According to Kristen A. Stilt, historical sources indicate that in Mamluk Egypt, poverty did "not necessarily excuse" the dhimmi from paying the tax, and boys as young as nine years old could be considered adults for tax purposes, making the tax particularly burdensome for large, poor families.[131] Ashtor and Bornstein-Makovetsky infer from Geniza documents that jizya was also collected in Egypt from the age of nine in the 11th century.[132]

Rate of the jizya tax

The rates of jizya were not uniform,[1] as Islamic scripture gave no fixed limits to the tax.[133] By the time of Mohammed, the jiyza rate was one dinar per year imposed on male dhimmis in Medina, Mecca, Khaibar, Yemen, and Nejran.[134] According to Muhammad Hamidullah, the rate was ten dirhams per year "in the time of the Prophet", but this amounted to only "the expenses of an average family for ten days".[135] Abu Yusuf, the chief qadhi of the caliph Harun al-Rashid, states that there was no amount permanently fixed for the tax, though the payment usually depended on wealth: the Kitab al-Kharaj of Abu Yusuf sets the amounts at 48 dirhams for the richest (e.g. moneychangers), 24 for those of moderate wealth, and 12 for craftsmen and manual laborers.[136][137] Moreover, it could be paid in kind if desired;[61][138][139] cattle, merchandise, household effects, even needles were to be accepted in lieu of specie (coins),[140] but not pigs, wine, or dead animals.[139][140]

The jizya varied in accordance with the affluence of the people of the region and their ability to pay. In this regard, Abu Ubayd ibn Sallam comments that the Prophet imposed 1 dinar (then worth 10 or 12 dirhams) upon each adult in Yemen. This was less than what Umar imposed upon the people of Syria and Iraq, the higher rate being due to the Yemenis greater affluence and ability to pay.[141]

The rate of jizya that were fixed and implemented by the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, namely 'Umar bin al-Khattab, during the period of his Khilafah, were small amounts: four dirhams from the rich, two dirhams from the middle class and only one dirham from the active poor who earned by working on wages, or by making or vending things.[142]

At least during one period, during the governorship of Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf in Iraq (680–714), the rate of jizya was sufficiently high and more than taxes on Muslims that officials of Al-Hajjaj's wrote to warn him that public revenues had greatly diminished because Christians were converting to Islam to avoid paying jizyah.[143]

The 13th-century scholar Al-Nawawī writes, "The minimum amount of the jizya is one dinar per person per annum; but it is commendable to raise the amount, if it be possible to two dinars, for those possessed of moderate means, and to four for rich persons."[144] Abu 'Ubayd insists that the dhimmis must not be burdened beyond their capacity, nor must they be caused to suffer.[145]

Scholar Ibn Qudamah (1147 – 7 July 1223) narrates three views on what the rates of jizya should be.

- That it is a fixed amount that can't be changed, a view that is reportedly shared by scholars of fiqh Abu Hanifa and al-Shafi'i.

- That it is up to the Imam (Muslim ruler) to make ijtihād (independent reasoning) so as to decide whether to add or decrease. He gives the example of 'Umar making particular amounts for each class (the rich, the middle class and the active poor).

- That there should be a strict minimum to be one dinar, but there is no upper limit.[146]

Scholar Ibn Khaldun (1332 – 17 March 1406) states that jizya has fixed limits that cannot be exceeded.[147] In the classical manual of Shafi'i fiqh Reliance of the Traveller it is stated that, "[t]he minimum non-Muslim poll tax is one dinar (n: 4.235 grams of gold) per person (A: per year). The maximum is whatever both sides agree upon."[148][149]

Collection methods

According to Al-Ghazali jizya was "to establish liberty of conscience in the world" and not for "compelling people to embrace Islam; that would be an unholy war."[135]

According to Mark R. Cohen, the Quran itself does not prescribe humiliating treatment for the dhimmi when paying Jizya, but some later Muslims interpreted it to contain "an equivocal warrant for debasing the dhimmi (non-Muslim) through a degrading method of remission".[150] In contrast, the 13th century hadith scholar and Shafi'ite jurist Al-Nawawī, comments on those who would impose a humiliation along with the paying of the jizya, stating, "As for this aforementioned practice, I know of no sound support for it in this respect, and it is only mentioned by the scholars of Khurasan. The majority of scholars say that the jizya is to be taken with gentleness, as one would receive a debt. The reliably correct opinion is that this practice is invalid and those who devised it should be refuted. It is not related that the Prophet or any of the rightly-guided caliphs did any such thing when collecting the jizya."[109][151][152] Ibn Qudamah also rejected this practice and noted that Muhammad and the Rashidun caliphs encouraged that jizya be collected with gentleness and kindness.[109][153][154]

Ann Lambton states that the jizya was to be paid "in humiliating conditions".[37] Many of the Islamic scholars base this on Surat At-Tawbah 9:29 which states – "(9:29) Those who do not believe in Allah and the Last Day – even though they were given the scriptures, and who do not hold as unlawful that which Allah and His Messenger have declared to be unlawful, and who do not follow the true religion – fight against them until they pay tribute out of their hand and are utterly subdued." Ennaji and other scholars state that some jurists required the jizya to be paid by each in person, by presenting himself, arriving on foot not horseback, by hand, in order to confirm that he lowers himself to being a subjected one, and willingly pays.[155][156][157]

The Maliki scholar Al-Qurtubi states, "their punishment in case of non-payment [of jizya] while they were able [to do so] is permitted; however, if their inability to pay it was clear then it isn't lawful to punish them, since, if one isn't able to pay the jizya, then he is exempted".[158] According to Abu Yusuf, jurist of the fifth Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid, those who didn't pay jizya should be imprisoned and not be let out of custody until payment; however, the collectors of the jizya were instructed to show leniency and avoid corporal punishment in case of non-payment.[137] If someone had agreed to pay jizya, leaving Muslim territory for enemy land was, in theory, punishable by enslavement if they were ever captured. This punishment did not apply if the person had suffered injustices from Muslims.[159]

Failure to pay the jizya was commonly punished by house arrest and some legal authorities allowed enslavement of dhimmis for non-payment of taxes.[160][161][162] In South Asia, for example, seizure of dhimmi families upon their failure to pay annual jizya was one of the two significant sources of slaves sold in the slave markets of Delhi Sultanate and Mughal era.[163]

Use of tax

Jizya was considered one of the basic tax revenues for the early Islamic state along with zakat, kharaj, and others.[164] and was collected by the Bayt al-Mal (public treasury).[165] Holger Weiss states that four fifths of the fay revenue, jizya and kharaj, goes to the public treasury according to the Shafi'i madhhab, whereas the Hanafi and Maliki madhhabs state that the entire fay goes to the public treasury.[166]

In theory, jizya funds were distributed as salaries for officials, pensions to the army and charity.[167] Cahen states, "But under this pretext it was often paid into the Prince's khass, "private" treasury."[167] In later times, jizya revenues were commonly allocated to Islamic scholars so that they would not have to accept money from sultans whose wealth came to be regarded as tainted.[37]

Sources disagree about expenditure of jizya funds on non-Muslims. Ann Lambton states that non-Muslims had no share in the benefits from the public treasury derived from jizya.[37] In contrast, according to several Muslim scholars, Islamic tradition records a number of episodes in which the second caliph, Umar, stipulated for needy and infirm dhimmis to be supported from the Bayt al-Mal, which some authors hold to be representative of Islam.[109][111][112][114][168][169] Evidence of jizya benefitting non-residents and temporary residents of an Islamic state is found in the treaty that Khalid bin al-Walid concluded with the people of Al-Hirah of Iraq in which any aged person who was weak, had lost his or her ability to work, fallen ill, or who had been rich but became poor, would be exempt from jiyza and his or livelihood and the livelihood of his or her dependents, who were not living permanently in the Islamic state, would be met by Bayt al-Mal.[170][171][172][173][174][175][176] Hasan Shah states that non-Muslim women, children, the indigent and slaves are exempted from the payment of jizya, and they are also helped by stipends from the public treasury when necessary.[65]

At least in the early Islamic era of the Umayyads, jizya was levy that sufficiently onerous for non-Muslims and its had a sufficiently significant revenue for rulers that there were more than a few accounts of non-Muslims seeking to convert to avoid paying it and revenue-conscious authorities denying them the opportunity.[85]

Robert Hoyland mentions repeated complaints by fiscal agents of revenues diminishing as conquered people converting to Islam, peasants attempting to convert and join the military but being rounded up and sent back to the countryside to pay taxes and governors circumventing the exemption on jizya for converts by requiring recitation of the Quran and circumcision.[85]

Patricia Seed describes the purpose of jizya as "a personal form of ritual humiliation directed at those defeated by a superior Islam" and quotes the Quranic verse calling for jizya: "Fight those who believe not in Allah... nor acknowledge the religion of truth... until they pay the jizya with willing submission and feel themselves subdued". She notes that the word translated as "subdued", ṣāghirūn, comes from the root ṣ-gh-r ("small", "little", "belittled" or "humbled").[177] Seed calls the idea that jizya was a contribution to help pay for the "military defense" of those who paid not a rationale but a rationalisation that was often found in societies in which the conquered paid tribute to conquerors.[178]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Origins

The history of the origins of the jizya is very complex for the following reasons:[179]

- Abbasid authors who systematized earlier historical writings in which the term jizya was used with different meanings interpreted it according to the usage common in their own time.

- The system established by the Arab conquest was not uniform but rather resulted from a variety of agreements or decisions.

- The earlier systems of taxation on which it was based are still imperfectly understood.[179]

William Montgomery Watt traces its origin to a pre-Islamic practice among the Arabian nomads in which a powerful tribe would agree to protect its weaker neighbors in exchange for a tribute that would be refunded if the protection proved ineffectual.[180] Robert Hoyland describes it as a poll tax originally paid by "the conquered people" to the mostly-Arab conquerors, but it later became a "religious tax, payable only by non-Muslims".[181]

Jews and Christians in some southern and eastern areas of the Arabian Peninsula began to pay tribute, called jizya, to the Islamic state during Muhammad's lifetime.[182] It was not originally the poll tax that it would become later but rather an annual percentage of produce and a fixed quantity of goods.[182]

During the Tabuk campaign in 630, Muhammad sent letters to four towns in the northern Hejaz and Palestine to urge them to relinquish maintenance of a military force and rely on Muslims to ensure their security in return for payment of taxes.[183] Moshe Gil argues that the texts represent the paradigm of letters of security that would be issued by Muslim leaders during the subsequent early conquests, including the use of the word jizya, which would later take on the meaning of poll tax.[183]

Jizya received divine sanction in 630, when the term was mentioned in a Quranic verse (9:29).[182] Max Bravmann argues that the Quranic usage of the word jizya develops a pre-Islamic common-law principle, which states that reward must necessarily follow a discretional good deed into a principle mandating that the life of all prisoners of war belonging to a certain category must be spared if they grant the "reward" (jizya) to be expected for an act of pardon.[184]

In 632, jizya, in the form of a poll tax, was first mentioned in a document that was reportedly sent by Muhammad to Yemen.[182] W. Montgomery Watt argues that the document was tampered with by early Muslim historians to reflect a later practice, but Norman Stillman holds it to be authentic.[182]

Emergence of classical taxation system

Taxes levied on local populations in the wake of early Islamic conquests could be of three types, based on whether they were levied on individuals, on the land, or as collective tribute.[179] During the first century of Islamic expansion, the words jizya and kharaj were used in all these three senses, with context distinguishing between individual and land taxes ("kharaj on the head," "jizya on land," and vice versa).[179][185] In the words of Dennett, "since we are talking in terms of history, not in terms of philology, the problem is not what the taxes were called, but what we know they were."[186] Regional variations in taxation at first reflected the diversity of previous systems.[187] The Sasanian Empire had a general tax on land and a poll tax having several rates based on wealth, with an exemption for aristocracy.[187] In Iraq, which was conquered mainly by force, Arabs controlled taxation through local administrators, keeping the graded poll tax, and likely increasing its rates to 1, 2 and 4 dinars.[187] The aristocracy exemption was assumed by the new Arab-Muslim elite and shared by local aristocracy by means of conversion.[187][188] The nature of Byzantine taxation remains partly unclear, but it appears to have involved taxes computed in proportion to agricultural production or number of working inhabitants in population centers.[187] In Syria and upper Mesopotamia, which largely surrendered under treaties, taxes were calculated in proportion to the number of inhabitants at a fixed rate (generally 1 dinar per head).[187][clarification needed] They were levied as collective tribute in population centers which preserved their autonomy and as a personal tax on large abandoned estates, often paid by peasants in produce.[187] In post-conquest Egypt, most communities were taxed using a system which combined a land tax with a poll tax of 2 dinars per head.[187][clarification needed] Collection of both was delegated to the community on the condition that the burden be divided among its members in the most equitable manner.[187] In most of Iran and Central Asia local rulers paid a fixed tribute and maintained their autonomy in tax collection, using the Sasanian dual tax system in regions like Khorasan.[187]

Difficulties in tax collection soon appeared.[187] Egyptian Copts, who had been skilled in tax evasion since Roman times, were able to avoid paying the taxes by entering monasteries, which were initially exempt from taxation, or simply by leaving the district where they were registered.[187] This prompted imposition of taxes on monks and introduction of movement controls.[187] In Iraq, many peasants who had fallen behind with their tax payments, converted to Islam and abandoned their land for Arab garrison cities in hope of escaping taxation.[187][189] Faced with a decline in agriculture and a treasury shortfall, the governor of Iraq al-Hajjaj forced peasant converts to return to their lands and subjected them to the taxes again, effectively forbidding peasants to convert to Islam.[190] In Khorasan, a similar phenomenon forced the native aristocracy to compensate for the shortfall in tax collection out of their own pockets, and they responded by persecuting peasant converts and imposing heavier taxes on poor Muslims.[190]

The situation where conversion to Islam was penalized in an Islamic state could not last, and the devout Umayyad caliph Umar II has been credited with changing the taxation system.[190] Modern historians doubt this account, although details of the transition to the system of taxation elaborated by Abbasid-era jurists are still unclear.[190] Umar II ordered governors to cease collection of taxes from Muslim converts,[191] but his successors obstructed this policy. Some governors sought to stem the tide of conversions by introducing additional requirements such as undergoing circumcision and the ability to recite passages from the Quran.[189] According to Hoyland, taxation-related grievances of non-Arab Muslims contributed to the opposition movements which resulted in the Abbasid revolution.[192] In contrast, Dennett states that it is incorrect to postulate an economic interpretation of the Abbasid Revolution. The notion of an Iranian population staggering under a burden of taxation and ready to revolt at the first opportunity, as imagined by Gerlof van Vloten, "will not bear the light of careful investigation", he continues.[193]

Under the new system that was eventually established, kharaj came to be regarded as a tax levied on the land, regardless of the taxpayer's religion.[190] The poll-tax was no longer levied on Muslims, but treasury did not necessarily suffer and converts did not gain as a result, since they had to pay zakat, which was instituted as a compulsory tax on Muslims around 730.[190][194] The terminology became specialized during the Abbasid era, so that kharaj no longer meant anything more than land tax, while the term "jizya" was restricted to the poll-tax on dhimmis.[190]

India

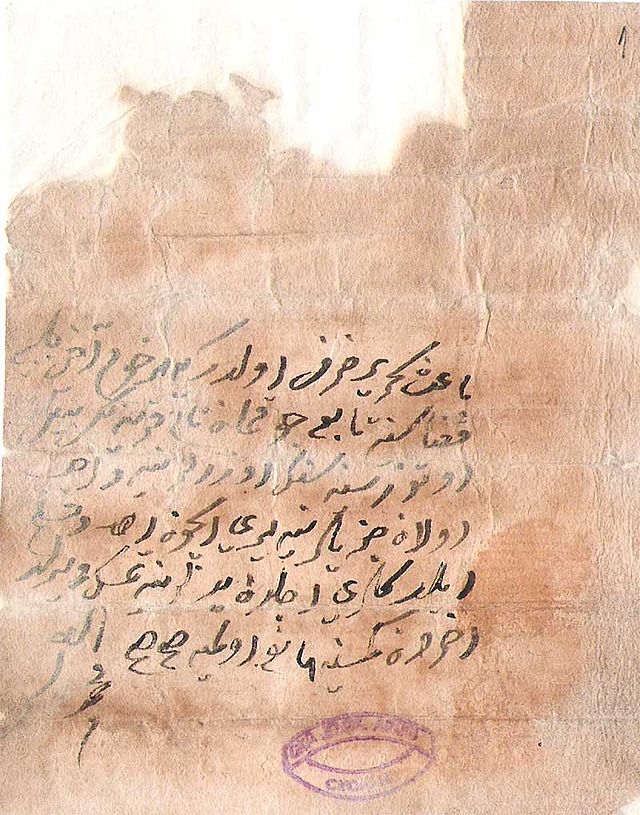

In India, Islamic rulers imposed jizya on non-Muslims starting with the 11th century.[195] The taxation practice included jizya and kharaj taxes. These terms were sometimes used interchangeably to mean poll tax and collective tribute, or just called kharaj-e-jizya.[196]

Jizya was expanded by the Delhi Sultanate. Alauddin Khilji legalized the enslavement of the jizya and kharaj defaulters. His officials seized and sold these slaves in growing Sultanate cities where there was a great demand of slave labour.[197] The Muslim court historian Ziauddin Barani recorded that Qazi Mughisuddin of Bayanah advised Alā' al-Dīn that Islam requires imposition of jizya on Hindus, to show contempt and to humiliate the Hindus, and imposing jizya is a religious duty of the Sultan.[198]

During the early 14th century reign of Muhammad bin Tughlaq, expensive invasions across India and his order to attack China by sending a portion of his army over the Himalayas, emptied the precious metal in the treasury of the Sultanate.[199][200] He ordered minting of coins from base metals with face value of precious metals. This economic experiment failed because Hindus in his Sultanate minted counterfeit coins from base metal in their homes, which they then used for paying jizya.[199][201] In the late 14th century, mentions the memoir of Tughlaq dynasty's Sultan Firoz Shah Tughlaq, his predecessor taxed all Hindus but had exempted all Hindu Brahmins from jizya; Firoz Shah extended it to also include the Brahmins at a reduced rate.[202][203] He also announced that any Hindu who converted to Islam would become exempt from taxes and jizya as well as receive gifts from him.[202][204] On those who chose to remain Hindus, he raised the jizya tax rate.[202]

In Kashmir, Sikandar Butshikan levied jizya on those who objected to the abolition of hereditary varnas, allegedly at the behest of his neo-convert minister Suhabhatta.[205][206] Ahmad Shah (1411–1442), a ruler of Gujarat, introduced the Jizyah in 1414 and collected it with such strictness that many people converted to Islam to evade it.[207]

Jizya was later abolished by the third Mughal emperor Akbar, in 1564.[208][209] However, in 1679, Aurangzeb chose to re-impose jizya on non-Muslim subjects in lieu of military service, a move that was sharply critiqued by many Hindu rulers and Mughal court-officials.[210][209][211][212] The specific amount varied with the socioeconomic status of a subject and tax-collection were often waived for regions hit by calamities; also, monks, musta'mins, women, children, elders, the handicapped, the unemployed, the ill, and the insane were all perpetually exempted.[213][211][214] The collectors were mandated to be Muslims.[209] In some areas revolts led to its periodic suspension such as the 1704 AD suspension of jizya in Deccan region of India by Aurangzeb.[215]

Southern Italy

After the Norman conquest of Sicily, taxes imposed on the Muslim minority were also called the jizya (locally spelled gisia).[216] This poll tax was a continuation of the jizya imposed on non-Muslims in the Emirate of Sicily and Bari by Islamic rulers of southern Italy, before the Norman conquest.[216]

Ottoman Empire

Jizya collected from Christian and Jewish communities was among the main sources of tax income of the Ottoman treasury.[28] In some regions, such as Lebanon and Egypt, jizya was payable collectively by the Christian or the Jewish community, and was referred to as maqtu—in these cases the individual rate of jizya tax would vary, as the community would pitch in for those who could not afford to pay.[217][218][page needed]

The Ottoman state also collected Jizya from Muslim and non-Muslim groups they registered as Gypsy (Kıpti), such as Roma in Western Anatolia and Balkans and Abdals, Doms and Loms in Kastamonu, Çankırı-Tosya, Ankara, Malatya, Harput, Antep, and Aleppo no later than late 17th century. Abdals and Tahtacıs in Teke (Antalya) were affiliated with another fiscal category, ifraz-ı zulkadriyye, until 1858, when the Ottoman reformers incorporated the fixed tax of relevant groups into the Gypsy poll tax.[219]

Abolition

In Persia, jizya was paid by the Zoroastrian minority until 1884, when it was removed by pressure on the Qajar government from the Persian Zoroastrian Amelioration Fund.[220]

The jizya was eliminated in Algeria and Tunisia in the 19th century, but continued to be collected in Morocco until the first decade of the 20th century (these three dates of abolition coincide with the French colonization of these countries).[221]

The Ottoman Empire abolished the jizya in 1856. It was replaced with a new tax, which non-Muslims paid in lieu of military service. It was called baddal-askari (lit. 'military substitution'), a tax exempting Jews and Christians from military service. The Jews of Kurdistan, according to the scholar Mordechai Zaken, preferred to pay the "baddal" tax in order to redeem themselves from military service. Only those incapable of paying the tax were drafted into the army. Zaken says that paying the tax was possible to an extent also during the war and some Jews paid 50 gold liras every year during World War I. According to Zaken, "in spite of the forceful conscription campaigns, some of the Jews were able to buy their exemption from conscription duty." Zaken states that the payment of the baddal askari during the war was a form of bribe that bought them at most a one-year deferment."[222]

Remove ads

In recent times

Summarize

Perspective

The jizya is no longer imposed by Muslim states.[33][167] Nevertheless, there have been reports of non-Muslims in areas controlled by the Pakistani Taliban and ISIS being forced to pay the jizya.[32][36]

In 2009, officials in the Peshawar region of Pakistan claimed that members of the Taliban forced the payment of jizya from Pakistan's minority Sikh community after occupying some of their homes and kidnapping a Sikh leader.[223] In 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) announced that it intended to extract jizya from Christians in the city of Raqqa, Syria, which it controlled.[citation needed]

In June, the Institute for the Study of War reported that ISIL claims to have collected the fay, i.e. jizya and kharaj.[224]

The late Islamic scholar Abul A'la Maududi, of Pakistan, said that Jizya should be re-imposed on non-Muslims in a Muslim nation.[82] Yusuf al-Qaradawi of Egypt also held that position in the mid-1980s;[225] however, he later reconsidered his legal opinion on this point, stating: "[n]owadays, after military conscription has become compulsory for all citizens—Muslims and non-Muslims—there is no longer room for any payment, whether by name of jizya or any other."[226] According to Khaled Abou El Fadl, moderate Muslims generally reject the dhimma system, which encompasses jizya, as inappropriate for the age of nation-states and democracies.[34]

Remove ads

Assessment and historical context

Summarize

Perspective

Some authors have characterized the complex of land and poll taxes in the pre-Abbasid era and implementation of the jizya poll tax in early modern South Asia as discriminatory and/or oppressive,[227][228][229][230][231] and the majority of Islamic scholars, amongst whom are Al-Nawawi and Ibn Qudamah, have criticized humiliating aspects of its collection as contrary to Islamic principles.[109][151][232][233] Discriminatory regulations were utilized by many pre-modern polities.[234] However, W. Cleveland and M. Bunton assert that dhimma status represented "an unusually tolerant attitude for the era and stood in marked contrast to the practices of the Byzantine Empire". They add that the change from the Byzantine and Persian rule to Arab rule lowered taxes and allowed dhimmis to enjoy a measure of communal autonomy.[235] According to Bernard Lewis, available evidence suggests that the change from Byzantine to Arab rule was "welcomed by many among the subject peoples, who found the new yoke far lighter than the old, both in taxation and in other matters".[236]

Ira Lapidus writes that the Arab-Muslim conquests followed a general pattern of nomadic conquests of settled regions, whereby conquering peoples became the new military elite and reached a compromise with the old elites by allowing them to retain local political, religious, and financial authority.[237] Peasants, workers, and merchants paid taxes, while members of the old and new elites collected them.[237] Payment of various taxes, the total of which for peasants often reached half of the value of their produce, was not only an economic burden, but also a mark of social inferiority.[237]

Norman Stillman writes that although the tax burden of the Jews under early Islamic rule was comparable to that under previous rulers, Christians of the Byzantine Empire (though not Christians of the Persian empire, whose status was similar to that of the Jews) and Zoroastrians of Iran shouldered a considerably heavier burden in the immediate aftermath of the Arab conquests.[228] He writes that escape from oppressive taxation and social inferiority was a "great inducement" to conversion and flight from villages to Arab garrison towns, and many converts to Islam "were sorely disappointed when they discovered that they were not to be permitted to go from being tribute bearers to pension receivers by the ruling Arab military elite," before their numbers forced an overhaul of the economic system in the 8th century.[228]

The influence of jizya on conversion has been a subject of scholarly debate.[238] Julius Wellhausen held that the poll tax amounted to so little that exemption from it did not constitute sufficient economic motive for conversion.[239] Similarly, Thomas Arnold states that jizya was "too moderate" to constitute a burden, "seeing that it released them from the compulsory military service that was incumbent on their Muslim fellow subjects." He further adds that converts escaping taxation would have to pay the legal alms, zakat, that is annually levied on most kinds of movable and immovable property.[240] Other early 20th century scholars suggested that non-Muslims converted to Islam en masse in order to escape the poll tax, but this theory has been challenged by more recent research.[238] Daniel Dennett has shown that other factors, such as desire to retain social status, had greater influence on this choice in the early Islamic period.[238] According to Halil İnalcık, the wish to avoid paying the jizya was an important incentive for conversion to Islam in the Balkans, though Anton Minkov has argued that it was only one among several motivating factors.[238]

Mark R. Cohen writes that despite the humiliating connotations and the financial burden, the jizya paid by Jews under Islamic rule provided a "surer guarantee of protection from non-Jewish hostility" than that possessed by Jews in the Latin West, where Jews "paid numerous and often unreasonably high and arbitrary taxes" in return for official protection, and where treatment of Jews was governed by charters which new rulers could alter at will upon accession or refuse to renew altogether.[241] The Pact of Umar, which stipulated that Muslims must "do battle to guard" the dhimmis and "put no burden on them greater than they can bear", was not always upheld, but it remained "a steadfast cornerstone of Islamic policy" into early modern times.[241]

Yaser Ellethy states that the "insignificant amount" of the jizya, as well as its progressive structure and exemptions leave no doubt that it was not imposed to persecute people or force them to convert.[14] Niaz A. Shah states that jizya is "partly symbolic and partly commutation for military service. As the amount is insignificant and exemptions are many, the symbolic nature predominates."[22] Muhammad Abdel-Haleem states, "[t]he jizya is a very clear example of the acceptance of a multiplicity of cultures within the Islamic system, which allowed people of different faiths to live according to their own faiths, all contributing to the well-being of the state, Muslims through zakāt, and the ahl al-dhimma through jizya."[242]

In his essay, ethnographer Shelomo Dov Goitein highlighted the limitation of studying the potential economic and other adverse social consequences of the jizya without any reference to non-Muslim sources:[243]

There is no subject of Islamic social history on which the present writer had to modify his views so radically while passing from literary to documentary sources, i.e., from the study of Muslim books to that of the records of the Cairo Geniza as the jizya...or the poll tax to be paid by non-Muslims. It was of course, evident that the tax represented a discrimination and was intended, according to the Koran's own words, to emphasize the inferior status of the non-believers. It seemed, however, that from the economic point of view, it did not constitute a heavy imposition, since it was on a sliding scale, approximately one, two, and four dinars, and thus adjusted to the financial capacity of the taxpayer. This impression proved to be entirely fallacious, for it did not take into consideration the immense extent of poverty and privation experienced by the masses, and in particular, their persistent lack of cash, which turned the "season of the tax" into one of horror, dread, and misery.

In 2016, Muslim scholars from more than 100 countries signed the Marrakesh Declaration, a document that called for a new Islamic jurisprudence based on the recognition of civic nationalism based governments, implying that the dhimmī system is inapplicable in the modern era in relation to the time of the writing of the Qur'an.[1]

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads