Jim Shooter

American comic book writer (born 1951) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

James Shooter (born September 27, 1951)[2] is an American writer, editor, and publisher in the comics industry. Beginning his career writing for DC Comics at the age of 14, he had a successful but controversial run as editor-in-chief at Marvel Comics, and launched comics publishers Valiant, Defiant, and Broadway.

| Jim Shooter | |

|---|---|

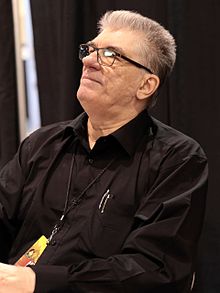

Shooter at the 2017 Phoenix Comicon | |

| Born | James Shooter September 27, 1951 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Area(s) | Writer, Penciller, Editor, Publisher |

| Pseudonym(s) | Paul Creddick |

Notable works | Adventure Comics Secret Wars Solar: Man of the Atom |

| Awards | Eagle Award (1979) Inkpot Award (1980)[1] |

| jimshooter | |

Early life

Jim Shooter was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to parents Ken and Eleanor "Ellie" Shooter,[3][4] who were of Polish descent.[5] Shooter read comics as a child, though he stopped when he was about eight years old. His interest in the medium was rekindled in 1963, at the age of twelve, while he recovered in a hospital after undergoing minor surgery. He was impressed with the style of Marvel Comics, which had only begun publication two years earlier. Thinking that if he learned to write the types of stories that Marvel published, he would be an asset to DC Comics – whose books, he felt, "needed the help" – Shooter spent about a year reading and studying comics from both companies.[6]

Career

Summarize

Perspective

DC Comics

At age 13, in mid-1965, Shooter wrote and drew stories featuring the Legion of Super-Heroes, and sent them in to DC Comics. On February 10, 1966, he received a phone call from Mort Weisinger, who wanted to purchase the stories Shooter had sent, and commissioned Shooter to write Supergirl and Superman stories. Weisinger eventually offered Shooter a regular position on Legion, and wanted Shooter to come to New York to spend a couple of days in his office. Shooter, who was 14 and lived in Pittsburgh, had to wait until school was in recess, after which he went to New York with his mother,[6] spurred in part by the need to support his financially struggling parents.[7][8][9][10]

According to Shooter, his father earned little as a steelworker,[11][12] and Shooter saw comic-book writing as a means of helping economically. Shooter reflected in a 2010 interview:

My family needed the money. I was doing this to save the house; my father had a beat-up old car and the engine died – this is before I started working for DC – and that first check bought a rebuilt engine for his car so he didn't have to walk to work anymore. I was doing this because I had to, working my way through high school to help keep my family alive.[6]

At 14, Shooter began selling stories to DC Comics, writing for both Action Comics and Adventure Comics, beginning with Adventure Comics No. 346 (July 1966),[13] and providing pencil breakdowns as well.[12] With considerable study of the writing style of DC Comics and of the recently rising Marvel Comics, Shooter created several characters for the Legion of Super-Heroes that benefited by him being one of the few writers at DC to understand the competitor's successful character-based narrative approach.[6] This included Legionnaires Karate Kid, Ferro Lad, and Princess Projectra, as well as the villainous group known as the Fatal Five. He also created the Superman villain the Parasite in Action Comics No. 340 (Aug. 1966).[14] Shooter and artist Curt Swan devised the first race between the Flash and Superman, two characters known for their superhuman speed, in "Superman's Race with the Flash!" in Superman #199 (Aug. 1967).[15] Shooter wrote the first issue of Captain Action (Oct.-Nov. 1968), which was DC's first toy tie-in.[16]

In 1969 Shooter was accepted into New York University, but after graduating from high school he successfully applied for a job at Marvel Comics. Unable to pursue both his studies and work for Marvel, he decided against going to New York University and quit working for DC as well.[17] While at Marvel he worked as an editor and occasional co-plotter, taking his residence at the YMCA, but after only three weeks his financial situation compelled him to give up the post and return home to Pittsburgh.[17]

After leaving Marvel, Shooter took up work in advertising concepts, writing, and illustration for several years, supporting himself through several menial jobs during periods when advertising work was unavailable. An interview for a Legion of Super-Heroes fanzine led to his again applying to both Marvel and DC. Though both companies offered him work, Shooter opted to return to DC because they had offered him more prestigious assignments: Superman and a chance to again write the Legion of Super-Heroes, now in their own book, Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes. However, Shooter's relationships with both Superman editor Julius Schwartz and Legion editor Murray Boltinoff were unpleasant, and he claims that both forced him to do unnecessary rewrites. In December 1975, Marvel editor-in-chief Marv Wolfman called to offer him an editorial position.[17]

Marvel Comics

In the mid-1970s, Marvel Comics was undergoing a series of changes in the position of editor-in-chief. After Roy Thomas stepped down from the post to focus on writing, a succession of other editors, including Len Wein, Marv Wolfman, Gerry Conway, and Archie Goodwin, took the job during a relatively short span of time, only to find the task too daunting as Marvel continued to grow and add new titles and a larger staff to turn out material.[18] On January 2, 1976, Shooter joined the Marvel staff as an assistant editor and writer.[17]

With the quick turnover at the top, Shooter rapidly found himself rising in the ranks, and on the first working day of January 1978, he succeeded Archie Goodwin to become Marvel's ninth editor-in-chief.[19][20] During this period, publisher Stan Lee relocated to Los Angeles to better oversee Marvel's animation, television and film projects, leaving Shooter largely in charge of the creative decision-making at Marvel's New York City headquarters. Although there were complaints among some that Shooter imposed a dictatorial style on the "Bullpen", he cured many of the procedural ills at Marvel, successfully managed to keep the line of books on schedule (ending the widespread practice of missed deadlines popularly known as "the Dreaded Deadline Doom"), added new titles, and developed new talent.[21] Shooter in his nine-year tenure as editor-in-chief oversaw Chris Claremont and John Byrne's run on the Uncanny X-Men,[22] Byrne's work on Fantastic Four,[23] Frank Miller's series of Daredevil stories,[24] Walt Simonson's crafting of Norse mythology with the Marvel Universe in Thor,[25] and Roger Stern's runs on both Avengers and The Amazing Spider-Man.

In 1981, Shooter brought Marvel into the lucrative comic book specialty shop market with Dazzler #1.[26] Featuring a disco-themed heroine with ties to the X-Men (based upon an unmade film set to star Bo Derek),[27] the first issue of this series was sold only through specialty stores, bypassing the then-standard newsstand/spinner rack distribution route altogether, as recognition by Marvel of the growing comics shop sector. Subsequent issues of Dazzler, however, were sold through newsstand [returnable] accounts as well. Dazzler was the first direct sales-only ongoing series from a major publisher; other Marvel titles, such as Marvel Fanfare and Ka-Zar, soon followed.[21][28] Later that same year, Shooter wrote Marvel Treasury Edition No. 28 which featured the second Superman and Spider-Man intercompany crossover.[29] Additionally in 1981, Shooter was recognized as one of six "New Yorkers of the Year" by the New York chapter of the JayCees, for his "contributions toward revitalizing the comics industry and helping Marvel Comics achieve a new pinnacle of success."[3] Shooter also institutionalized creator royalties,[citation needed] starting the Epic imprint for creator-owned material in 1982; introduced company-wide crossover events, with Marvel Super Hero Contest of Champions and Secret Wars;[30] and launched a new, albeit ultimately unsuccessful, line named New Universe, to commemorate Marvel's 25th anniversary, in 1986.[31]

Despite his success in revitalizing Marvel, Shooter angered and alienated a number of long-time Marvel creators by insisting on strong editorial control and strict adherence to deadlines.[18] Although he instituted an art-return program, and implemented a policy giving creators royalties when their books passed certain sales benchmarks or when characters they worked on were licensed as toys, Shooter occasionally found himself in well-publicized conflicts with some writers and artists. Creators such as Steve Gerber, Marv Wolfman,[32][33] Gene Colan,[33][34] John Byrne,[35] and Doug Moench left to work for DC (encouraged by its new publisher, Jenette Kahn, aggressively taking advantage of the opportunity) or other companies.[32][36]

During Shooter's tenure, he enforced a policy forbidding the portrayal of gay characters in the Marvel universe.[37][38][39] According to John Byrne, he initially had to conceal Northstar's sexuality, since Shooter personally told him that portraying a gay character would not be allowed.[40][41] Marvel nonetheless published the first gay-themed story by a mainstream comics publisher during this time, written by Shooter himself; in it, two gay men attempt to rape Bruce Banner.[39][42] Comics historian Frederick Luis Aldama says that Marvel under Shooter's tenure "was widely considered homophobic."[43]

Roy Thomas, who left Marvel following a contract dispute with Shooter, reflected in 2005 on Shooter's editorial policies:

When Jim Shooter took over, for better or worse he decided to rein things in – he wanted stories told the way he wanted them told. It's not a matter of whether Jim Shooter was right or wrong; it's a matter of a different approach. He was editor-in-chief and had a right to impose what he wanted to. I thought it was kind of dumb, but I don't think Jim was dumb. I think the approach was wrong, and I don't think it really helped anything.[44]

John Romita Sr. said:

Shooter had been great for the first two or three years. He got the creative people treated with more respect, got us sent to conventions first-class with our ways paid, and we thought the world of him. Then his Secret Wars was a big hit, and after that he decided he knew everything and he started changing everybody's stuff.[45]

John Byrne said similarly:

Shooter came along just when Marvel needed him – but he stayed too long. Having fixed just about everything that was wrong, he could not stop "fixing". Around the time I left to do Superman, I said that I thought Shooter and Dick Giordano should trade jobs – it was DC that needed fixing then – and do so about every 5 years or so. Shooter had put Marvel into a place where all that was needed was a kindly father figure at the helm – and that was not Shooter! ... Secret Wars ... was when the trouble really kicked into high gear.[46] We must never forget that SECRET WARS began as a toy promotion. ... Shooter turned it into a way to reshape the Marvel Universe in his image.[47]

Valiant Comics

Shooter and his investors then founded a new company, Voyager Communications, which published comics under the Valiant Comics banner, entering the market in 1989 with comics based on Nintendo and WWF licensed characters. Two years later Valiant entered the superhero market with a relaunch of the Gold Key Comics character Magnus, Robot Fighter. Another Gold Key character, Solar, Man of the Atom was also relaunched later in the same year. Shooter brought many of Marvel's creators to Valiant, including Bob Layton and Barry Windsor-Smith, as well as industry veterans such as Don Perlin. Valiant also established "knob row", in which creators were taught how to render the company's comics in the Valiant style.[50]

Occasionally over the years, Shooter was required to fill in as penciller on various books he wrote or oversaw as editor. During his period as Valiant's publisher, money and talent were often at a premium, and Shooter was sporadically forced to pencil a story. To conceal this fact, he drew under the pseudonym of Paul Creddick, the name of his brother-in-law.[51]

Defiant and Broadway Comics

After being ousted from Valiant in 1992,[52] Shooter and several of his co-workers went on to found Defiant Comics in early 1993.[53] Despite some initial success with the first title, the new company failed to secure an audience in the increasingly crowded direct sales market and went out of business after thirteen months of publishing.[54]

In 1995, Shooter founded Broadway Comics, which was an offshoot of Broadway Video,[55] the production company that produces Saturday Night Live, but this line ended after its parent sold the properties to Golden Books.[56] In 1998, he spoke of a planned self-publishing, Daring Comics, with a projected eight titles including Anomalies and Rathh of God, with artist Joe James scheduled to draw at least one.[57]

Shooter returned to Valiant, by now called Acclaim Comics, briefly in 1999 to write Unity 2000 (an attempt to combine and revitalize the older and newer Valiant Universes) but Acclaim went out of business after the completion of only three of the planned six issues.

2000s–present

In 2003, Jim Shooter joined custom comics company Illustrated Media as creative director and editor in chief.[58]

In 2005, former Marvel Comics letterer Denise Wohl approached Shooter to create Seven, a series based on the Kabbalah.[59] Writer Shooter created a team of seven characters, one from each continent, who are brought together in New York because they share a higher consciousness.[60] The project, which was to be self-published by Wohl, was announced at the 2007 New York Comic Con, to debut in July of that year, and was projected to "evolve into television and film projects, video games, blogs, interactive Q&A, animation, trading cards, apparel, accessories, [and] school supplies." Wohl was to donate a portion of her proceeds to the "Spirituality for Kids Foundation."[61] Only the first issue of the series has been published.[62]

In September 2007, DC Comics announced that Shooter would be the new writer of the Legion of Super-Heroes vol. 5 series, beginning with issue #37.[63] Shooter's return to the Legion, a little over 30 years from his previous run, was his first major published comic book work in years. Shooter co-created the new Legionnaire Gazelle with artist Francis Manapul while on the title. His run on the series ended with issue No. 49, one issue before the book was canceled.

Shooter was hired by Valiant Entertainment, a company that bought Valiant's intellectual property in a bankruptcy auction of Acclaim Entertainment, to write from the end of 2008 into the summer of 2009.[64]

In July 2009 Dark Horse Comics announced at San Diego Comic-Con that Shooter would oversee the publication of new series based on Gold Key Comics characters from the Silver Age of Comic Books, such as Turok, Doctor Solar, and Magnus: Robot Fighter, and write some of them as well.[65] Valiant sued Shooter over his moving to write the Gold Key characters for Dark Horse as they expected to get the rights and that he interfered with their ability to license the Key characters by indicating that he would write them for Dark Horse.[64] As of January 2010, Valiant had given up the lawsuit against Shooter.[66] He subsequently wrote the relaunched Magnus: Robotfighter, Turok and Dr. Solar series as well as Mighty Samson, another Gold Key character (that had not been picked up by Valiant Comics), for Dark Horse, beginning in 2010.

As of 2023, Shooter still works as consulting editor and freelance writer for custom comics company Illustrated Media.[67][68]

Awards and recognition

- 1979 Eagle Award for Best Continuing Story (with George Pérez, Sal Buscema and David Wenzel for The Avengers No. 167, 168, 170–177)[69]

- 1980 Inkpot Award[70]

- January 2012 Inkwell Awards Ambassador (January 2012 – present)[71]

- Jim Shooter is the subject of a volume of the University Press of Mississippi's Conversations with Comic Artists series, published in 2017.

Bibliography

Summarize

Perspective

As writer unless otherwise noted.

Acclaim Comics

- Unity 2000 #1–3 (#4–6 unpublished) (1999–2000)

- The Valiant Deaths of Jack Boniface #1–2 (flip-book with Shadowman vol. 3 #3–4) (1999)

American Mythology Productions

- Bedtime Stories for Impressionable Children #1 (2017)

Beyond Comics

- The Writer's Block #1 (2001)

Broadway Comics

- Fatale #1–6 (1996)

- Fatale Preview Edition #1 (1995)

- Knights on Broadway #1 (1996)

- Powers That Be #1–6 (1995–1996)

- Powers That Be Preview Edition #1–2 (1995)

- Shadow State #1–5 (1995–1996)

- Shadow State Preview Edition #1–2 (1995)

- Star Seed #7–9 (1996)

Dark Horse Comics

- Doctor Solar, Man of the Atom #1–8 (2010–2011)

- Magnus, Robot Fighter #1–4 (2010–2011)

- Mighty Samson #1–4 (2010–2011)

- Predator vs. Magnus Robot Fighter #1–2 (1992)

- Turok, Son of Stone #1–4 (2010–2011)

DC Comics

- Action Comics #339–340, 342–345, 348, 361, 378, 380–382, 384, 451–452 (1966–1975)

- Adventure Comics #346–349, 352–355, 357–380 (as writer/artist) (1966–1969)

- Captain Action #1–2 (1968)

- Legion of Super-Heroes vol. 5 #37–49 (2008–2009)

- Superboy #135, 140–141, 209–215, 217, 219–224 (1967–1977)

- Superman #190–191, 195, 199, 206, 220, 290 (1966–1975)

- Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #97, 99, 106, 110, 121, 123 (1966–1969)

- World's Finest Comics #162–163, 166, 172–173, 177 (1966–1968)

Defiant Comics

- Charlemagne #1 (1994)

- Dark Dominion #0, 3–4, 6 (1993–1994)

- Dogs of War #1 (1994)

- The Good Guys #1, 3–6 (1993–1994)

- Plasm #0 (1993)

- War Dancer #1–3 (1994)

- Warriors of Plasm #1–7 (1993–1994)

Intrinsic Comics

- Seven #1 (2007)

Marvel Comics

- The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21 (1987)

- The Avengers #151, 156, 158–168, 170–177, 188, 200–202, 204, 211–222, 224, 266 (1976–1986)

- Black Panther #13 (1979)

- Captain America #232, 259 (1979–1981)

- Daredevil #141, 144–151, 223 (1977–1985)

- Dazzler #29, 31–32, 35 (1983–1985)

- The Defenders #69 (1979)

- Dreadstar #1 (text article) (1982)

- Fantastic Four #182–183, 296 (1977–1986)

- Fantastic Four Roast #1 (1982)

- Ghost Rider #19, 23–27, 57 (as layout artist for #57) (1976–1981)

- Heroes for Hope: Starring the X-Men #1 (1985)

- The Hulk! #23 (1980)

- Iron Man #90, 129 (1976–1979)

- Marvel Chillers #7 (1976)

- Marvel Fanfare No. 1, 4–7, 9, 11, 13, 17, 19 (text articles for all and one page illustration for #11) (1982–1985)

- Marvel Fumetti Book #1 (1984)

- Marvel Graphic Novel No. 12, 16 (1984–1985)

- Marvel Super-Heroes #11 (1992)

- Marvel Team-Up #107, 126 (1981–1983)

- Marvel Treasury Edition #28 (1981)

- Marvel Two-in-One #23–24 (1977)

- Ms. Marvel #5 (1977)

- Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe #6 (one page illustration) (1983)

- Phoenix: The Untold Story #1 (1984)

- The Saga of Crystar, Crystal Warrior #1 (text article) (1983)

- Secret Wars #1–12 (1984–1985)

- Secret Wars II #1–9 (1985–1986)

- The Spectacular Spider-Man vol. 2, #3, 56–57, 59 (as layout artist for #56–57 and 59) (1977–1981)

- Star Brand #1–7 (1986–1987)

- Super-Villain Team-Up #3, 9 (as artist for #9) (1975–1976)

- Team America #1–2, 8, 11, 12 (1982–1983)

- Thor #385 (1987)

- The Tomb of Dracula vol. 2 #6 (1980)

- Web of Spider-Man #22, 34 (1987–1988)

- What If ... ? #3, 34 (1977–1982)

- X-Men vs. The Avengers #4 (plotter) (1987)

Valiant Comics

- Archer & Armstrong #0, 1–2 (1992)

- Eternal Warrior #1–3 (1992)

- Harbinger #1–10 (1992)

- Magnus, Robot Fighter #0, 1–16, 18–20 (as writer/artist for #5) (1991–1993)

- Nintendo Comics System #1 (as artist) (1991)

- Rai #1–4 (insert in Magnus, Robot Fighter #5–8) (1991–1992)

- Rai vol. 2 #7, 0 (1992)

- Shadowman #1–2, 4–6 (1992)

- Solar, Man of the Atom #1–15 (1991–1992)

- Unity #0–1 (1992)

- World Wrestling Federation: Lifestyles of the Brutal and Infamous (1991)

- X-O Manowar #1–3, 5–6 (1992)

Valiant Entertainment

- Harbinger: The Beginning HC (new short story) (2007)

- Archer & Armstrong: First Impressions HC (new short story) (2008)

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.