Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Ivan Đaja

Serbian biologist, physiologist, author and philosopher From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

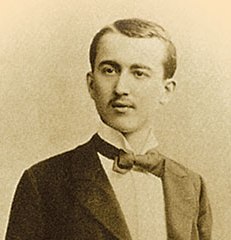

Ivan Đaja (Serbian Cyrillic: Иван Ђаја, French: Jean Giaja; 21 July 1884 – 1 October 1957) was a Serbian[2] biologist, physiologist, author and philosopher.

Remove ads

He was founder of the Chair for physiology at the Serbian Institute for Physiology, rector of the University of Belgrade, and member of the Serbian Academy of Science and Arts.[3][4][5][6] Đaja was a popularizer of biology, performed research in the role of the adrenal glands in thermoregulation, as well as pioneering work in hypothermia.[1][4][7][8]

He has been described as the "restless researcher of the secret of life", who left a valuable creative and human mark in Serbian society, which was mostly pushed aside in the previous decades.[9]

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Đaja was born on 21 July 1884 in Le Havre, a major port in Normandy, France. His mother, Delphine Depois-Auger (1861, Ontere-1902, Belgrade), was French. She was a daughter of the local ship-owner. His father Božidar “Boža” Đaja (1850, Dubrovnik-1914, Hinterbrühl) was a ship master, originally working as a sea captain, later switching to river transportation.[5][10][11] They were married in Le Havre in 1881.[12] Ivan was their eldest child. While they were still living in France, the couple had another son, Aleksandar (1885–1968), who later became an agronomist within the Food Institute of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts.[5][12] When Ivan was six, the family moved to Belgrade in 1890, where his father took over as the captain of a steamboat, Deligrad,[10][11] which was an official diplomatic ship of Serbian rulers. He helmed it until his retirement in 1907. In Belgrade, the couple had a daughter, Olga, their third child (1892–1974).[12]

Božidar was also an author. He wrote stories about the life of Dalmatian sailors who worked on the sailing ships and published them in the series of books jointly titled Our Seamen: Apprentice in 1903, Young Man in 1904 and Helmsman in 1909, all three published by the Ilija M. Kolarac Endowment. When he died in Vienna, he left three more manuscripts from the same series, ready for print: Nostromo, Captain and Old Age.[13]

Remove ads

Education

Summarize

Perspective

Đaja finished elementary and high school in Belgrade. After graduating at First Belgrade Gymnasium in 1902, he moved back to France, spending one year as a student at the Lycée Pierre-Corneille at Rouen.[5][10] He studied philosophy under Émile Chartier.[8] In 1903 he enrolled at the Sorbonne, where one of his fellow students and best friends was Émile Herzog, later famous French author under the name Andre Maurois. He studied natural sciences (botany, physiology and biochemistry) under Albert Dastre, great scientific experimenter, himself a student of Claude Bernard. Đaja gave his final exam in 1905 and, mentored by Dastre, received a PhD on 23 July 1909 with the thesis in physiology Study on ferments of glycosides and carbohydrates in mollusks and crustaceans.[1][3][8]

During his studying, he also had several jobs. In 1904, he became the youngest foreign correspondent of Serbian daily Politika. Only 20 years old, he became recently established newspaper's reporter from Paris and first foreign correspondent in general.[5] He also worked for a while at National Museum of Natural History with Paul van Tieghem, before spending five years at Marine station in Roscoff, Brittany. Starting in 1906, he worked there with Yves Delage and Albert Dastre, beginning his career as a researcher.[8]

Remove ads

Academic career

Summarize

Perspective

University

He was invited by the biologist Živojin Đorđević to return to Belgrade from France, where he became a docent at the Faculty of Philosophy.[14] There, that same year, he founded the first Chair for physiology in this part of the world, within the Institute for Physiology which he also founded and chaired for 40 years.[1][3][4][5][8] When World War I broke out in 1914, he was in Vienna, and was kept in confinement, under the Austro-Hungarian police watch, until December 1918.[5][8][14]

Upon his return to Srbija, Đaja restored the Institute and became associate professor at the University's Faculty of Philosophy in 1919 obtaining the full professorship in 1921. In 1947, when Faculty for mathematics and natural sciences (PMF) split from the Faculty of Philosophy, Đaja became PMF's professor.[1][2] In 1934 he was elected to the one-year tenure as the rector of the University of Belgrade. He founded and co-founded numerous scientific institutes both in Yugoslavia and abroad, including People's University in Belgrade.[1][3][5][14] He was vice-president of the Red Cross of Yugoslavia in the Interbellum.[11]

World War II interrupted his work again, as Đaja staunchly opposed the German-appointed puppet regime in Serbia. He asked to be retired in 1942 and was even confined for a while by the quisling authorities at the Banjica concentration camp. He was reactivated in 1945, both as the professor and head of the Institute for Physiology, before finally retiring in 1955.[5][8][14]

Academies

He became associate member of the Serbian Royal Academy on 18 February 1922, and was elected to the full membership on 16 February 1931.[15] Within the Academy, he was member of Academy of natural sciences and its secretary from 7 March 1937 to 7 March 1939. He gave his inaugural academic address on 6 March 1932, titled Some features of the fight against cold.[16] After reorganization of the Academy in 1947, Đaja was elected a member of Department for mathematics and natural sciences and Department for medical sciences on 22 March 1948. He became secretary of the former from that date to 10 June 1952, while he was entrusted with developing the latter and creating a new Department for arts and music (he himself played a flute. He became member of that department, too, on 20 April 1949. In the process of reorganization, Serbian Royal Academy was renamed Serbian Academy of Science in 1947. Đaja later proposed for the name to be expanded by adding arts in the title, which was accepted after his death, in 1960, when the academy was officially renamed to Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

Soon after becoming an associated member of the Serbian academy, he was elected to the same position in Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts in Zagreb. He helmed the process of collaboration between the two academies in an effort to realize his idea of creating a biology station for students located on the Adriatic Sea. As a result, Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries was founded in 1930 in Split, on the Dalmatian coast (today in Croatia).[8][11]

Đaja was also a member of the French Academy of Sciences.[2][6] He was unanimously elected as a corresponding member in 1955,[3] being inaugurated on 28 May 1956 in the Section for medicine and surgery.[17] He was elected for his “seminal work on the behaviour of deep cooled warm blooded animals” and took over the academy seat which was left vacant after the death of Alexander Fleming.[8]

Remove ads

Scientific career

Summarize

Perspective

After he founded the Institute, Đaja began his experimental work, adopting the motto Nulla dies sine experimentum (Not one day without the experiment).[5] His entire scientific work can be divided into three phases. In the first phase, which started in his student days and lasted up to World War I, he concentrated on the research of the endogenic enzymes or ferments, which are produced by the glands of digestive organs. He created a more rational nomenclature of the enzymes than the ones previously used.

When he returned to Serbia in 1919, his second phase was centered on metabolism. In this period, he published a physiology textbook in 1923, Fundamentals of physiology. In preface, he wrote that “he arranged the subject matter based on one leading idea: that circulation of matter and energy is the basic phenomenon of life, and that all physiological functions are subordinated to it.” He also researched bioenergetics and an effect of the temperature and asphyxia induced numbness on living organisms. His major work from this phase is the two-volume Homeothermy and thermoregulation from 1938.

Đaja began to research hypothermia in 1935 and from 1940 it became the focal point of his scientific work. He was especially interested in the ways it can be achieved. With his treatise State similar to the winter sleep of the hibernators achieved in rat by the means of barometric depression, published on 15 January 1940, he began researching the physiology of the deeply cooled homeothermous organisms. He was interested in thermogenesis, gas circulation in organisms, adaptation to cold, defense role of hypothermia and metabolism in deep hypothermia. His results from this period have found a wide application in medical physiology.

Apart from pure chemical processes in the human body, he was interested in philosophical decoding of the complex functional plexus in the natural world in general. Considering physiology as the branch of biology which synthesizes the entire knowledge of the science of life, Đaja aimed to present the philosophical interpretation of the nature of science, its foundations and future development. He published his philosophical views in Following the footsteps of life and science in 1931 and Man and the inventive life in 1955. He presented thesis on the origin of the biological inventive power, purposefulness of certain phenomena in the living world and discussed the concept of usefulness in biology. He tried to comprehend the mechanics of life, chemistry and physical chemistry of the living organisms and to give a unifying scientific philosophical theory which would encompass physiology, evolution and genetics.[14]

He was also known as the major popularizer of biology, but also of science and arts in general and was remembered as an excellent lecturer and teacher.[6][8]

Remove ads

Personal life

Đaja married three times. His first wife was French and she died young. He married for the second time to Sofija Đaja,[12] village teacher from Bavanište, Pančevo. They had a daughter, Ivanka Đaja-Milanković (1934–2002). Ivanka worked as a journalist in Sremska Mitrovica, where she died, though she spent a long time living in Canada. Already at an advanced age, he married for the third time, to Leposava Marković (1910–1991). She was his former student and collaborator and worked as an assistant and professor at the University of Belgrade. They lived in Belgrade's neighborhood of Profesorska Kolonija. Đaja was a good friend with Milutin Milanković.[11]

His paternal uncle was Jovan Đaja (1846–1928), a journalist and politician, member of Nikola Pašić’s People's Radical Party. He was president of Serbian association of journalists 1897–1899 and Minister of internal affairs of Serbia 1890–1891 and 1891–1892.[18] He was the one who invited Ivan's father Božidar to Belgrade, to helm the "Deligrad" ship.[12]

Remove ads

Death

In 1957, as president of the Symposium on hypothermia, Đaja was among the principal organizers of the XV congress of the Committee of International Congresses of Military Medicine and Pharmacy which was held in Belgrade. During the congress, on his way to the venue, Đaja died on 1 October 1957. Among many others, the scientific journal Nature marked his passing by publishing an In memoriam.[8]

Writings

Summarize

Perspective

Alone, or with his co-workers, Đaja authored over 250 works, out of which over 200 were scientific. Rest of it includes popular, philosophical and children books, translations from French and an autobiography.

He co-authored his first scientific paper in 1906, titled Amylolytic inactivity of dialyzed pancreatic juice. His other initial studies were also centred on enzymology and published in magazines of the Parisian Biology society and French Academy of Sciences. Later, his works were mostly published by the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts and Croatian Natural Society. Since 1913 he was correspondent for the Glasnik, magazine of the Serbian academy, and later for the Medical overview, Serbian literary herald from 1905, Foreign review from 1933 and Science and technics from 1941. In 1927–1928 he was an editor of the University's magazine University life.

After publishing his PhD thesis Study on ferments of glycosides and carbohydrates in mollusks and crustaceans in 1909, his first monograph was Ferments and physiology in 1912 and other important works in the next decade include Notes on a scientific work (1914), Biology papers (1918), Fundamental biological energy and energetics of kvass (1919), Does living yeast cause fermentation of sugar only by its zymase? (1919), Use of ferments in cell physiology studies (1919), Fundamental biological energy (1920), About electric thermostate (1920) and Experimental search for the common energetic foundation in living beings (1921), while in 1923 he published the first textbook on human and animal physiology in the region, Fundamentals of physiology.[11] Other scientific works include Mutual replacement of food ingredients in peak metabolism (1926), Basal metabolism and homeothermy (1929), Peak metabolism (1929), Problem of evolution (1931), Homeothermy and thermoregulation I-II (1938) and Hypothermia, hyberniation and poikilotherms (1953). Monograph Man and the inventive life, published in 1955, is considered to be his opus magnum.

Popular and philosophical works include Travels of “Obilić” through South Serbia in 1923 (1929), Following the footsteps of life and science (1931), From life to civilization (1933), How do we feed? (1935), Louis Pasteur (1937), Downstream (1938), Twosome conversations (1938) and The look into life (1955), while writings aimed at the children include Tales of little Zdravko: book for children on nature, hygiene and health (1923) and What European youth thinks (1929).

In the last year of his life, 1957, he published five papers, while his last article, entitled For the scientific youth, was published in Politika on the eve of his death. When he died, he left several writings in manuscripts: Conversations in Dubrovnik, Short stories, Memories, Physiology and hypothermia and his autobiography Discovery of the world.[1][2][4][7][8][14][19]

Critics say that "true word about Đaja, as a writer, still hasn't been said". Starting with his first non-scientific works published in the Srđ magazine, he was described as a natural born storyteller. His meditative prose is said to have a "specific place" in Serbian literature. He was also writing down his thoughts in the form of saying and proverbs.[12]

Remove ads

Importance and legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Ivan Đaja is one of the greatest Serbian physiologists and biologists who had the invaluable role in founding the experimentally based scientific physiology in Serbia. Gifted scientist, teacher, philosopher, writer and musician, he was a true modern polymath. As such, he was the founder of biochemistry in Serbia and Southeast Europe. His work brought him a worldwide reputation.[4][8]

He was among the first scientists who pointed out the role of the adrenal glands in the body's thermoregulation[1][14] and is considered one of the pioneers in the research of hypothermia. He founded the new scientific branch, high altitude hypothermia (or physiology of the cooled organisms) which has a growing application in modern medicine, much more than it had in Đaja's time.[3][14] At one point, based on his research, the NASA examined the possibility of bringing the astronauts to the state of hypothermia, which would bring them to the hibernation stasis and make longer space flights possible.[9]

A diagram he created in 1938 is today known as the Đaja’s diagram (of thermoregulation) or Đaja’s curve,[1][3][14][20] and the way he brought organisms to hypothermia (reducing the body temperature by asphyxia and cold environment and then complete recovery by warming up the organism) is named Đaja’s method of induced hypothermia (“hypercapnian hypothermia”).[3][4] Đaja also invented an apparatus for gas exchange measurement (Đaja’s apparatus). He coined the terms peak (or maximal) metabolism and metabolic quotient which entered the textbooks on the subject.[1][14]

In the Institute for Physiology of Serbia, which he founded in 1910 and made a world class scientific facility, he was succeeded by his student Radoslav Anđus (1926–2003) who continued his work and the resulting scientific approach became known as the “Belgrade School of physiology“.[3][8][14] Due to the intensive work of Đaja on establishing and keeping the professional links with foreign universities, he placed the Belgrade physiology school on a world map.[9]

Commemoration named "100 years of Ivan Đaja's Belgrade school of physiology" was organized from 10 to 14 September 2010 by the University of Belgrade's Faculty of Biology. The event was held in the premises of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Artsm with participation of scientists from the United States, United Kingdom, Sweden, Germany, Slovakia, etc. A bust of Ivan Đaja was dedicated during the event, which was later moved to the hall of the Faculty of Biology.[11]

Remove ads

Accolades

Already for his first monograph from 1912, “Ferments and Physiology”, Đaja received an award from the Serbian Royal Academy of Sciences.[8]

For his studies on hypothermia and thermoregulation, French Academy of Sciences awarded him the Pourat prize in 1940 and the Montyon Prize in 1946.[1][7][8][14]

In 1952 he was elected a corresponding member of the French Académie Nationale de Médecine.[9] In 1954 he was awarded the doctor honoris causa at the Sorbonne, and was also awarded the French Legion of Honour.[1][3][8] He was the third Serbian scientist who was awarded Sorbonne's honorary degree, after Nikola Tesla and Jovan Cvijić.[14] He was also an associate member of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris.[2]

In Belgrade's municipality of Vračar, a street was named in Đaja's honor in 2004.[21][22] Celebrating 100 years of the Institute for Physiology, a commemorative plaque was placed in the street on 10 September 2010.[11]

He was the recipient of the Serbian Order of the White Eagle, 4th class and Yugoslav Order of Labour, I rank.[2]

Public image

Summarize

Perspective

Đaja was described as a "man completely devoid of vanity".[9] He is remembered as a proper gentleman, always suitably dressed and groomed, and cultural and kind in communication with others. Đaja was also known as propagating humanistic approach, always helping his co-workers and students. With his students, he organized and participated in transfer of the Josif Pančić remains from Belgrade to the Kopaonik mountain. He was known for joking, saying to his friends: "Come by too see my daughter, she is the best in the field of physiology I have done".[11] This was in line with his understanding that "life, by itself is more perfect than any human achievement".[9]

During his tenure at the helm of the University of Belgrade in 1934–1935, a major anti-government student protest was organized and to put it down, the police stormed the university. Đaja then supported the students, staunchly protesting the police action. After the war, when the Communists took over the government, he was introduced to the new authoritarian ruler Josip Broz Tito in 1945 as the "students mother and red rector". Đaja replied: "I protected them so that they can study, their political fervor I considered a youthful frivolity". When Tito was nominated as the honorable member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Đaja was the only one who voted against him. As a result, the secret service labeled him as "reactionary and misfit". When he was inaugurated to the French Academy of sciences in 1956, Yugoslavia refused to send an ambassador. Đaja stated: "He was free to come, I criticize my country only when I'm in it". Though allowed to work and teach at the university, and to publish popular and other books, none of his scientific books were published in Yugoslavia after his fallout with Tito.[9][11]

Remove ads

Gallery

|

|

Citations

General sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads