Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Orthomyxoviridae

Family of RNA viruses including the influenza viruses From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Orthomyxoviridae (from Ancient Greek ὀρθός (orthós) 'straight' and μύξα (mýxa) 'mucus')[1] is a family of negative-sense RNA viruses. It includes nine genera: Alphainfluenzavirus, Betainfluenzavirus, Gammainfluenzavirus, Deltainfluenzavirus, Isavirus, Mykissvirus, Quaranjavirus, Sardinovirus, and Thogotovirus. The first four genera contain viruses that cause influenza in birds (see also avian influenza) and mammals, including humans. Isaviruses infect salmon; the thogotoviruses are arboviruses, infecting vertebrates and invertebrates (such as ticks and mosquitoes).[2][3][4] The Quaranjaviruses are also arboviruses, infecting vertebrates (birds) and invertebrates (arthropods).

The four genera of Influenza virus that infect vertebrates, which are identified by antigenic differences in their nucleoprotein and matrix protein, are as follows:

- Alphainfluenzavirus infects humans, other mammals, and birds, and causes all flu pandemics

- Betainfluenzavirus infects humans and seals

- Gammainfluenzavirus infects humans and pigs

- Deltainfluenzavirus infects pigs and cattle.

Remove ads

Structure

The influenzavirus virion is pleomorphic; the viral envelope can occur in spherical and filamentous forms. In general, the virus's morphology is ellipsoidal with particles 100–120 nm in diameter, or filamentous with particles 80–100 nm in diameter and up to 20 μm long.[5] There are approximately 500 distinct spike-like surface projections in the envelope each projecting 10–14 nm from the surface with varying surface densities. The major glycoprotein (HA) spike is interposed irregularly by clusters of neuraminidase (NA) spikes, with a ratio of HA to NA of about 10 to 1.[6]

The viral envelope composed of a lipid bilayer membrane in which the glycoprotein spikes are anchored encloses the nucleocapsids; nucleoproteins of different sizes; the arrangement within the virion is uncertain. The ribonuclear proteins are filamentous and fall in the range of 50–150 nm long with helical symmetry.[7]

Remove ads

Genome

Summarize

Perspective

Viruses of the family Orthomyxoviridae contain six to eight segments of linear negative-sense single stranded RNA. They have a total genome length that is 10,000–14,600 nucleotides (nt).[7] The influenza A genome, for instance, has eight pieces of segmented negative-sense RNA (13.5 kilobases total).[8]

The best-characterised of the influenzavirus proteins are hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, two large glycoproteins found on the outside of the viral particles. Hemagglutinin is a lectin that mediates binding of the virus to target cells and entry of the viral genome into the target cell.[9] In contrast, neuraminidase is an enzyme involved in the release of progeny virus from infected cells, by cleaving sugars that bind the mature viral particles. The hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) proteins are key targets for antibodies and antiviral drugs,[10][11] and they are used to classify the different serotypes of influenza A viruses, hence the H and N in H5N1.

The genome sequence has terminal repeated sequences, and these are repeated at both ends (i.e., at both the 5’ end and the 3’ end). These terminal repeats at the 5′-end are 12–13 nucleotides long. Nucleotide sequences at the 3′-terminus are identical, are the same in genera of the same family, most on RNA (segments), or on all RNA species. Terminal repeats at the 3′-end are 9–11 nucleotides long. Encapsidated nucleic acid is solely genomic. Each virion may contain defective interfering copies. In Influenza A (specifically, in H1N1) PB1-F2 is produced from an alternative reading frame in PB1. The M and NS genes produce two genes each (4 genes total) via alternative splicing.[12]

Remove ads

Replication cycle

Summarize

Perspective

Typically, influenza is transmitted from infected mammals through the air by coughs or sneezes, creating aerosols containing the virus, and from infected birds through their droppings. Influenza can also be transmitted by saliva, nasal secretions, feces and blood. Infections occur through contact with these bodily fluids or with contaminated surfaces. On certain surfaces (i.e, outside of a host), flu viruses can remain infectious for about one week at human body temperature, over 30 days at 0 °C (32 °F), and indefinitely at very low temperatures (such as in lakes in northeast Siberia). They can be inactivated easily by disinfectants and detergents.[13][14][15]

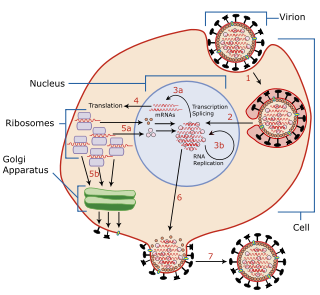

The viruses interacts between its surface hemagglutinin glycoprotein to bind to the host's surface sialic acid sugars, specifically on the surfaces of epithelial cells in the lung and throat (Stage 1 in infection figure).[16] The cell imports the virus by endocytosis. In the acidic pH environment of the endosome, part of the hemagglutinin protein fuses the viral envelope with the vacuole's membrane, releasing: the viral RNA (vRNA) molecules, accessory proteins and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase into the host cell's cytoplasm (Stage 2).[17] These proteins and vRNA form a complex that is transported into the host cell nucleus, where the host's own RNA-dependent RNA polymerase begins transcribing complementary positive-sense cRNA (Steps 3a and b).[18] The cRNA is either exported into the cytoplasm and translated (step 4), or remains in the host nucleus. Newly synthesised viral proteins are either secreted through the Golgi apparatus onto the host cell surface (in the case of neuraminidase and hemagglutinin, step 5b) or transported into the host nucleus, where they bind vRNA and form new viral genome particles (step 5a). Other viral proteins have multiple actions in the host cell, including degrading cellular mRNA and using those consequently-released nucleotides for vRNA synthesis, while also inhibiting translation of the host cell's mRNAs.[19]

A virion assembles from negative-sense vRNAs (that form the genomes of newly created viruses), RNA-dependent RNA transcriptase and other viral proteins. Hemagglutinin and neuraminidase molecules cluster into a bulge in the host cell membrane. The vRNA and viral core proteins leave the nucleus and enter this membrane protrusion (step 6). The mature virus buds off from the host cell in a sphere of host phospholipid membrane, acquiring hemagglutinin and neuraminidase with this membrane coat (step 7).[20] As before, the viruses then adhere to the same host cell capsule through hemagglutinin; the mature viruses detach once their neuraminidase has cleaved sialic acid residues from the host cell.[16] After the release of new influenza virus, the host cell dies, and infection repeats in other host cells.

Orthomyxoviridae viruses are one of two RNA viruses that replicate in the nucleus (the other being retroviridae). This is because the machinery of orthomyxo viruses cannot make their own mRNAs. They use cellular RNAs as primers for initiating the viral mRNA synthesis in a process known as cap snatching.[21] Once in the nucleus, the RNA Polymerase Protein PB2 finds a cellular pre-mRNA and binds to its 5′ capped end. Then RNA Polymerase PA cleaves off the cellular mRNA near the 5′ end and uses this capped fragment as a primer for transcribing the rest of the viral RNA genome in viral mRNA.[22] This is due to the need of mRNA to have a 5′ cap in order to be recognized by the cell's ribosome for translation.

Since RNA proofreading enzymes are absent, the RNA-dependent RNA transcriptase makes a single nucleotide insertion error roughly every 10 thousand nucleotides, which is the approximate length of the influenza vRNA. Hence, nearly every newly manufactured influenza virus will contain a mutation in its genome.[23] The separation of the genome into eight separate segments of vRNA allows mixing (reassortment) of the genes if more than one variety of influenza virus has infected the same cell (superinfection). The resulting alteration in the genome segments packaged into viral progeny confers new behavior, sometimes the ability to infect new host species or to overcome protective immunity of host populations to its old genome (in which case it is called an antigenic shift).[10]

Remove ads

Classification

In a phylogenetic-based taxonomy, RNA viruses include the subcategory negative-sense ssRNA virus, which includes the order Articulavirales, and the family Orthomyxoviridae. The family contains the following genera:[24]

- Alphainfluenzavirus

- Betainfluenzavirus

- Deltainfluenzavirus

- Gammainfluenzavirus

- Isavirus

- Mykissvirus

- Quaranjavirus

- Sardinovirus

- Thogotovirus

Influenza types

Summarize

Perspective

There are four genera of influenza virus, each containing only a single species, or type. Influenza A and C infect a variety of species (including humans), while influenza B almost exclusively infects humans, and influenza D infects cattle and pigs.[25][26][27]

Influenza A

Influenza A viruses are further classified, based on the viral surface proteins hemagglutinin (HA or H) and neuraminidase (NA or N). 18 HA subtypes (or serotypes) and 11 NA subtypes of influenza A virus have been isolated in nature. Among these, the HA subtype 1-16 and NA subtype 1-9 are found in wild waterfowl and shorebirds and the HA subtypes 17-18 and NA subtypes 10-11 have only been isolated from bats.[28][29]

Further variation exists; thus, specific influenza strain isolates are identified by the Influenza virus nomenclature,[30] specifying virus type, host species (if not human), geographical location where first isolated, laboratory reference, year of isolation, and HA and NA subtype.[31][32]

Examples of the nomenclature are:

- A/Brisbane/59/2007 (H1N1) - isolated from a human

- A/swine/South Dakota/152B/2009 (H1N2) - isolated from a pig

The type A influenza viruses are the most virulent human pathogens among the three influenza types and cause the most severe disease. It is thought that all influenza A viruses causing outbreaks or pandemics originate from wild aquatic birds.[33] All influenza A virus pandemics since the 1900s were caused by Avian influenza, through Reassortment with other influenza strains, either those that affect humans (seasonal flu) or those affecting other animals (see 2009 swine flu pandemic).[34] The serotypes that have been confirmed in humans, ordered by the number of confirmed human deaths, are:

- H1N1 caused "Spanish flu" in 1918 and "Swine flu" in 2009.[35]

- H2N2 caused "Asian Flu".

- H3N2 caused "Hong Kong Flu".

- H5N1, "avian" or "bird flu".[36]

- H7N7 has unusual zoonotic potential.[37]

- H1N2 infects pigs and humans.[38]

- H9N2, H7N2, H7N3, H10N7.

Influenza B

Influenza B virus is almost exclusively a human pathogen, and is less common than influenza A. The only other animal known to be susceptible to influenza B infection is the seal.[46] This type of influenza mutates at a rate 2–3 times lower than type A[47] and consequently is less genetically diverse, with only one influenza B serotype.[25] As a result of this lack of antigenic diversity, a degree of immunity to influenza B is usually acquired at an early age. However, influenza B mutates enough that lasting immunity is not possible.[48] This reduced rate of antigenic change, combined with its limited host range (inhibiting cross species antigenic shift), ensures that pandemics of influenza B do not occur.[49]

Influenza C

The influenza C virus infects humans and pigs, and can cause severe illness and local epidemics.[50] However, influenza C is less common than the other types and usually causes mild disease in children.[51][52]

Influenza D

This is a genus that was classified in 2016, the members of which were first isolated in 2011.[53] This genus appears to be most closely related to Influenza C, from which it diverged several hundred years ago.[54] There are at least two extant strains of this genus.[55] The main hosts appear to be cattle, but the virus has been known to infect pigs as well.

Remove ads

Epidemiology

Summarize

Perspective

Evolution and history

The predominant natural reservoir of influenza viruses is thought to be wild waterfowl.[56] A 2023 involving total RNA sequencing and transcriptome mining found that Influenzaviruses and the broader Articulavirales order likely had an aquatic origin, with fish being some of the earliest hosts, and the earliest viruses in the order evolving from Crustaceans over 600 million years ago.[57] The subtypes of influenza A virus are estimated to have diverged 2,000 years ago. Influenza viruses A and B are estimated to have diverged from a single ancestor around 4,000 years ago, while the ancestor of influenza viruses A and B and the ancestor of influenza virus C are estimated to have diverged from a common ancestor around 8,000 years ago.[58]

Outbreaks of influenza-like disease can be found throughout recorded history. The first probable record is by Hippocrates in 412 BCE.[59] The historian Fujikawa listed 46 epidemics of flu-like illness in Japan between 862 and 1868.[60] In Europe and the Americas, a number of epidemics were recorded through the Middle Ages and up to the end of the 19th century.[59]

In 1918–1919 came the first flu pandemic of the 20th century, known generally as the "Spanish flu", which caused an estimated 20 to 50 million deaths worldwide. It is now known that this was caused by an immunologically novel H1N1 subtype of influenza A.[61] The next pandemic took place in 1957, the "Asian flu", which was caused by a H2N2 subtype of the virus in which the genome segments coding for HA and NA appeared to have derived from avian influenza strains by reassortment, while the remainder of the genome was descended from the 1918 virus.[62] The 1968 pandemic ("Hong Kong flu") was caused by a H3N2 subtype in which the NA segment was derived from the 1957 virus, while the HA segment had been reassorted from an avian strain of influenza.[62]

In the 21st century, a strain of H1N1 flu (since titled "H1N1pdm09") was antigenically very different from previous H1N1 strains, leading to a pandemic in 2009. Because of its close resemblance to some strains circulating in pigs, this became known as "swine flu".[63]

Influenza A virus continues to circulate and evolve in birds and pigs. Almost all possible combinations of H (1 through 16) and N (1 through 11) have been isolated from wild birds.[64] As of June 2024, two particularly virulent IAV strains - H5N1 and H7N9 – are predominant in wild bird populations. These frequently cause outbreaks in domestic poultry, with occasional spillover infections in humans who are in close contact with poultry.[65][66]

Pandemic potential

Influenza viruses have a relatively high mutation rate that is characteristic of RNA viruses.[67] The segmentation of the influenza A virus genome facilitates genetic recombination by segment reassortment in hosts who become infected with two different strains of influenza viruses at the same time.[68][69] With reassortment between strains, an avian strain which does not affect humans may acquire characteristics from a different strain which enable it to infect and pass between humans – a zoonotic event.[70] It is thought that all influenza A viruses causing outbreaks or pandemics among humans since the 1900s originated from strains circulating in wild aquatic birds through reassortment with other influenza strains.[71][72] It is possible (though not certain) that pigs may act as an intermediate host for reassortment.[73]

Surveillance

The Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) is a global network of laboratories that monitor the spread of influenza with the aim to provide the World Health Organization with influenza control information and to inform vaccine development.[74] Several millions of specimens are tested by the GISRS network annually through a network of laboratories in 127 countries.[75] As well as human viruses, GISRS also monitors avian, swine, and other potentially zoonotic influenza viruses.

Seasonal flu

Flu season is an annually recurring time period characterized by the prevalence of an outbreak of influenza, caused either by Influenza A or by Influenza B. The season occurs during the cold half of the year in temperate regions; November through February in the northern hemisphere and May to October in the southern hemisphere. Flu seasons also exist in the tropics and subtropics, with variability from region to region.[77] Annually, about 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness and 290,000 to 650,000 deaths from seasonal flu occur worldwide.[78]

There are several possible reasons for the winter peak in temperate regions:

- During the winter, people spend more time indoors with the windows sealed, so they are more likely to breathe the same air as someone who has the flu and thus contract the virus.[79]

- Days are shorter during the winter, and lack of sunlight leads to low levels of vitamin D and melatonin, both of which require sunlight for their generation. This compromises our immune systems, which in turn decreases ability to fight the virus.[79]

- The influenza virus may survive better in colder, drier climates, and therefore be able to infect more people.[79]

- Cold air reduces the ability of the nasal membranes to resist infection.[80]

Zoonotic infections

A zoonosis is a disease in a human caused by a pathogen (such as a bacterium, or virus) that has jumped from a non-human to a human.[81][82] Avian and pig influenza viruses can, on rare occasions, transmit to humans and cause zoonotic influenza virus infections; these infections are usually confined to people who have been in close contact with infected animals or material such as infected feces and meat, they do not spread to other humans. Symptoms of these infections in humans vary greatly; some are in asymptomatic or mild while others can cause severe disease, leading to severe pneumonia and death.[83] A wide range of Influenza A virus subtypes have been found to cause zoonotic disease.[83][84]

Zoonotic infections can be prevented by good hygiene, by preventing farmed animals from coming into contact with wild animals, and by using appropriate personal protective equipment.[82]

As of June 2024, there is concern about two subtypes of avian influenza which are circulating in wild bird populations worldwide, H5N1 and H7N9. Both of these have potential to devastate poultry stocks, and both have jumped to humans with relatively high case fatality rates.[84] H5N1 in particular has infected a wide range of mammals and may be adapting to mammalian hosts.[85]

Remove ads

Signs and symptoms

Summarize

Perspective

Humans

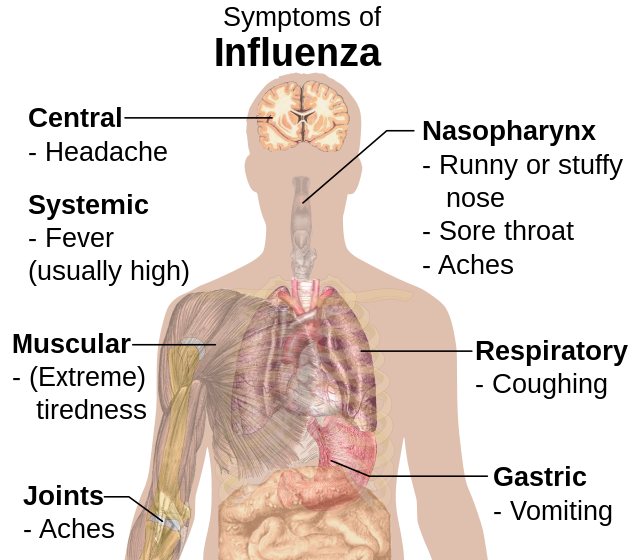

The symptoms of seasonal flu are similar to those of a cold, although usually more severe and less likely to include a runny nose.[89] The onset of symptoms is sudden, and initial symptoms are predominately non-specific: a sudden fever; muscle aches; cough; fatigue; sore throat; headache; difficulty sleeping; loss of appetite; diarrhoea or abdominal pain; nausea and vomiting.[90]

Humans can rarely become infected with strains of avian or swine influenza, usually as a result of close contact with infected animals or contaminated material; symptoms generally resemble seasonal flu but occasionally can be severe, including death.[91][92]

Other animals

Birds

Some species of wild aquatic birds act as natural asymptomatic carriers of a large variety of influenza A viruses, which they can spread over large distances in their annual migration.[93] Symptoms of avian influenza vary according to both the strain of virus underlying the infection, and on the species of bird affected. Symptoms of influenza in birds may include swollen head, watery eyes, unresponsiveness, lack of coordination, respiratory distress such as sneezing or gurgling.[94]

Highly pathogenic avian influenza

Because of the impact of avian influenza on economically important chicken farms, avian virus strains are classified as either highly pathogenic (and therefore potentially requiring vigorous control measures) or low pathogenic. The test for this is based solely on the effect on chickens - a virus strain is highly pathogenic avian influenza if 75% or more of chickens die after being deliberately infected with it, or if it is genetically similar to such a strain. The alternative classification is low pathogenic avian influenza.[95] Classification of a virus strain as either a low or high pathogenic strain is based on the severity of symptoms in domestic chickens and does not predict severity of symptoms in other species. Chickens infected with low pathogenic avian influenza display mild symptoms or are asymptomatic, whereas highly pathogenic avian influenza causes serious breathing difficulties, significant drop in egg production, and sudden death.[96]

Since 2006, the World Organization for Animal Health requires all detections of low pathogenic avian influenza H5 and H7 subtypes to be reported because of their potential to mutate into highly pathogenic strains.[97]

Pigs

Signs of swine flu in pigs can include fever, depression, coughing (barking), discharge from the nose or eyes, sneezing, breathing difficulties, eye redness or inflammation, and going off feed. Some pigs infected with influenza, however, may show no signs of illness at all. Swine flu subtypes are principally H1N1, H1N2, and H3N2;[98] it is spread either through close contact between animals or by the movement of contaminated equipment between farms.[99] Humans who are in close contact with pigs can sometimes become infected.[100]

Horses

Equine influenza can affect horses, donkeys, and mules;[101] it has a very high rate of transmission among horses, and a relatively short incubation time of one to three days.[102] Clinical signs of equine influenza include fever, nasal discharge, have a dry, hacking cough, depression, loss of appetite and weakness.[102] EI is caused by two subtypes of influenza A viruses: H7N7 and H3N8, which have evolved from avian influenza A viruses.[103]

Dogs

Most animals infected with canine influenza A will show symptoms such as coughing, runny nose, fever, lethargy, eye discharge, and a reduced appetite lasting anywhere from 2–3 weeks.[104] There are two different influenza A dog flu viruses: one is an H3N8 virus and the other is an H3N2 virus.[104] The H3N8 strain has evolved from an equine influenza avian virus which has adapted to sustained transmission among dogs. The H3N2 strain is derived from an avian influenza which jumped to dogs in 2004 in either Korea or China.[104] It is likely that the virus persists in both animal shelters and kennels, as well as in farms where dogs are raised for meat production.[105]

Bats

The first bat flu virus, IAV(H17N10), was first discovered in 2009 in little yellow-shouldered bats (Sturnira lilium) in Guatemala.[106] In 2012 a second bat influenza A virus IAV(H18N11) was discovered in flat-faced fruit-eating bats (Artibeus planirostris) from Peru.[107][108][109] Bat influenza viruses have been found to be poorly adapted to non-bat species.[110]

Remove ads

Viability and disinfection

Mammalian influenza viruses tend to be labile, but they can survive several hours in a host's mucus.[111] Avian influenza virus can survive for 100 days in distilled water at room temperature and for 200 days at 17 °C (63 °F). The avian virus is inactivated more quickly in manure but can survive for up to two weeks in feces on cages. Avian influenza viruses can survive indefinitely when frozen.[111] Influenza viruses are susceptible to bleach, 70% ethanol, aldehydes, oxidizing agents and quaternary ammonium compounds. They are inactivated by heat at 133 °F (56 °C) for minimum of 60 minutes, as well as by low pH <2.[111]

Remove ads

Vaccination and prophylaxis

Summarize

Perspective

Vaccines and drugs are available for the prophylaxis and treatment of influenza virus infections. Vaccines are composed of either inactivated or live attenuated virions of the H1N1 and H3N2 human influenza A viruses, as well as those of influenza B viruses. Because the antigenicities of the wild viruses evolve, vaccines are reformulated annually by updating the seed strains.[112]

More specifically, flu vaccines are made using the reassortment method, and this has been used for over 50 years. In this method, scientists inject eggs with both one noninfectious flu strain and also one infectious strain. The inert strain must be one that multiples very well in chicken eggs. Scientists pick an infectious strain that carries the desired HA and N receptors that the final product should prevent from infection. They choose these strains by picking the surface HA and NA versions circulating the most in the public, and the ones thought most likely to be prevalent in the upcoming flu season. The two strains—pathogenic and non pathogenic—then multiply and exchange DNA until an inert strain carries eight copies of the infectious strain's two glycoprotein targets. Finally, of the newly created viruses, scientists pick six versions that multiplied the best in chicken eggs which also carry the necessary HA and NA genes. Ultimately, millions of eggs are injected with those noninfectious strains—which carry the desired proteins—so that the genes can be harvested and used for the vaccine product.[112]

Another method of making the vaccine is by splicing genes from infectious strains and then creating copies in a lab, without the need for the tedious process of chicken egg culture. This method relies on using virus plasmids to excerpt the target genes.[112]

When the antigenicities of the seed strains and wild viruses do not match, vaccines fail to protect the vaccines.[112]

Drugs available for the treatment of influenza include Amantadine and Rimantadine, which inhibit the uncoating of virions by interfering with M2 proton channel, and Oseltamivir (marketed under the brand name Tamiflu), Zanamivir, and Peramivir, which inhibit the release of virions from infected cells by interfering with NA. However, escape mutants are often generated for the former drug and less frequently for the latter drug.[113]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads