Indiana gas boom

Period of active drilling in northeast Indiana From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

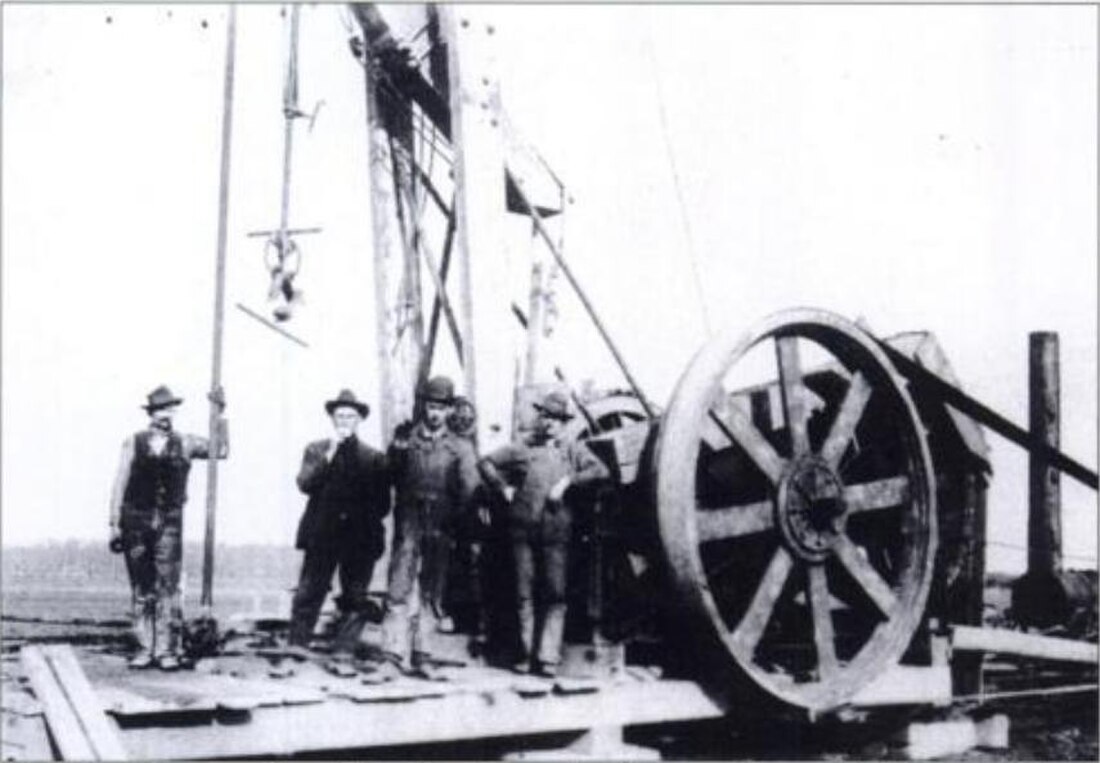

The Indiana gas boom was a period of active drilling and production of natural gas in the Trenton Gas Field, in the US state of Indiana and the adjacent northwest part of Ohio. The boom began in the early 1880s and lasted into the early 20th century.

When the Indiana natural gas belt was discovered, the citizens were unaware of what they had found. Nearly a decade passed without action to recover the resource. Once its significance was realized, further exploration showed the Indiana gas belt was the largest deposit of natural gas discovered until then. In addition to the massive quantity of natural gas, in the 1890s developers discovered that the field also contained the first giant oil reserve found in the US, with an estimated one billion barrels of oil. The resource was rapidly tapped for use. Because the gas was being wasted in use, the Indiana General Assembly attempted to regulate its use. In a series of cases, the Indiana Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the law.

The poor understanding of oil and gas wells at the time led to the loss of an estimated 90% of the natural gas by venting into the atmosphere or by widespread misuse. By 1902, yield from the fields began to decline, leading to a switch to alternative forms of energy. With most of the gas removed from the field, there was no longer enough pressure to pump the oil out of the ground. An estimated 900 million barrels (140 million cubic meters) of oil remain in the field.

Discovery

Summarize

Perspective

Natural gas was first discovered in Indiana in 1876. Coal miners in the town of Eaton were boring a hole in search of coal. After they reached a depth of about 600 feet (180 m), a loud noise came from the ground and a foul odor came from the hole. The event scared the miners. Some believed that they had breached the ceiling of Hell. They plugged the hole and did not drill any more at that location.[1]

In 1886, Indiana's first commercial gas well was established when George W. Carter, William W. Worthington, and Robert C. Bell hired Almeron H. Crannell to drill another well in Eaton. Crannell reached gas at a depth of 922 feet (281 m). When the escaping gas was ignited, the flame reached 10 feet into the air. Other gas wells were drilled, and in instances, the escaping gas was ignited to advertise the discovery, with the assumption that the gas was inexhaustible. The resultant flame was called a flambeaux.[2]

Gas fever swept the state and thousands of gas wells were created. Explorers found that the gas field was the largest of natural gas fields found up to that date,[3] covering an area of 5,120 square miles (13,300 km2). The belt came to be called the Trenton Gas Field. Drillers found large quantities of oil in addition to the natural gas.[1]

Boom

Summarize

Perspective

The gas discovery stimulated the development of industry in East Central Indiana. The Ball Corporation, a manufacturer of glass canning jars, relocated from Buffalo to Muncie, attracted by land and monetary incentives offered by local leaders, as well as easy access to cheap fuel for their production lines.[4] Other manufacturers also moved into the area, including the Kokomo Rubber Company; Hemmingray Bottle and Insulating Glass Company; and Maring, Hart, and Company.

Iron and other metal manufacturers, also attracted by economic incentives, established factories throughout the region. The low cost of energy was a primary reason U.S. Steel chose Indiana for their operations. Other cities across East Central Indiana also grew, including Hartford City and Gas City. Gas City was in the center of the gas field and had access to the strongest pressures, with between 300 pounds per square inch (2,100 kPa) and 350 pounds per square inch (2,400 kPa).

One major use for the gas was to power lighting,[1] which created demand for gas exports to cities across the Midwest. The boom led to rapid development of pumping and piping technology by the region’s gas and oil companies. Inventors and engineers, such as Elwood Haynes, developed many different methods that advanced the industry. The Indiana Natural Gas and Oil Company, formed by a group of Chicago businessmen led by Charles Yerkes, hired Haynes as their superintendent in 1890.[5] He oversaw the laying of the first long-distance natural gas pipeline in the US, connecting Chicago with the Trenton Field over 150 miles (240 km) away.

The wealth and industry brought by the wells led to a rapid population shift throughout Indiana. In 1890, Gas City had a population of 145, but two years later the Gas City Land Company platted 1,200 acres (490 ha) in anticipation of a population increase to 25,000. Although Gas City did not reach 25,000 in population, its population still increased over 2,000 percent. By 1893, Gas City businesses employed more than 4,000 workers.[4] Between 1880 and 1900, the population of Muncie quadrupled, from 5,219 to 20,942, including notable increases in the Black population relative to other similar-sized towns throughout the state.[6]

Decline

Summarize

Perspective

As the use of the gas grew, many scientists warned that more gas was being wasted than was effectively used by industry, and that the supplies would soon run out. Almost every town in northern Indiana had one or more gas wells. Many were purchased by local governments, which used revenues for community amenities. Many towns and cities installed free gas lighting throughout their communities, supplied by their own gas wells.[7] Communities also piped gas to private homes to provide cheap heating fuel, helping to make urban living more desirable. Gas was used to produce electricity that ran electric street cars in several cities. Businessmen also established corporations to purchase the gas from the local markets and sell it wholesale on the national market.[8] Producers lit a flambeau atop each well to demonstrate the gas was flowing, a practice that wasted massive amounts of gas each day.

An 1893 report by Indiana natural gas supervisor E. T. J. Jordan noted that gas pressure had declined sharply throughout the region between 1887 and 1892.[9] The Indiana General Assembly attempted to limit gas waste by prohibiting open burning and instituting a system of metered consumption to encourage energy conservation, but the law met with tough opposition. Many town leaders, who had come to rely on the gas revenues, dismissed claims that the wells would run dry.

By the turn of the century, output from the wells began to decline. Some flambeaus had been burning for nearly two decades; slowly their flames became shorter and weaker. Modern experts estimate that as much as 90% of the natural gas was wasted in flambeau displays.[10] By 1903, factories' and towns' need for alternate sources of energy led to creation of numerous coal-burning electric plants.

By 1910, the once-abundant resources had slowed to a trickle. By then new industry had moved into the state, and decline of the gas industry did not have a major negative impact. The availability of cheap energy had drawn so much new industry that Indiana had become one of the leading industrial states. The economy of northern Indiana continued to flourish until the Great Depression began in the following decade.

Environmental impact

Summarize

Perspective

In total, over 1 trillion cubic feet (28 km3) of natural gas and 105 million barrels (16.7 million cubic meters) of oil are estimated to have been extracted from the field.[11]

Smaller pockets of natural gas exist in Indiana at depths that could not be reached in the boom era. The state still had a small natural gas-producing industry in 2008, but residents and industry consume about twice as much natural gas as the state produces. In 2005 there were 338 active natural gas wells on the Trenton Field. In 2006 Indiana produced more than 290 million cubic feet (8.2 million cubic meters) of natural gas. This made it the 24th-largest-producing state, far below the major producers.[12]

It is estimated that only 10% of the oil was drilled from the Trenton Field, and approximately 900 million barrels (140 million cubic meters) may remain. Because of the size of the field, pumping gas back into the well to increase pressure, as is commonly done in smaller fields, is impossible. Because of the depth and limitations of hydraulic pumps, it was never cost effective to use them to extract oil. Advancements in artificial lift technology in the 1990s led to extraction of some of the oil, but at a relatively slow rate and high cost compared to more productive fields elsewhere.[13]

See also

Notes

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.