Territories of the United States

Overview of U.S. overseas territories From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indian reservations in that they are not sovereign entities.[note 2] In contrast, each state has a sovereignty separate from that of the federal government and each federally recognized Native American tribe possesses limited tribal sovereignty as a "dependent sovereign nation".[2] Territories are classified by incorporation and whether they have an "organized" government established by an organic act passed by the Congress.[3] American territories are under American sovereignty and may be treated as part of the U.S. proper in some ways and not others (i.e., territories belong to, but are not considered part of the U.S.).[4] Unincorporated territories in particular are not considered to be integral parts of the U.S.,[5] and the Constitution of the United States applies only partially in those territories.[6][7][3][8][9]

Territories of the United States | |

|---|---|

Incorporated, unorganized territory

Unincorporated, organized territory

Unincorporated, unorganized territory

Sovereign states in Compacts of Free Association with the United States (Palau, Marshall Islands, Micronesia) | |

| Languages | |

| Demonym(s) | American |

| Territories |

9 uninhabited 2 claimed |

| Leaders | |

| Donald Trump | |

| List | |

| Area | |

• Total | 22,294.19 km2 (8,607.83 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2020 census | 3,623,895 |

| Currency | United States dollar |

| Date format | mm/dd/yyyy (AD) |

The U.S. administers three[6][10] territories in the Caribbean Sea and eleven in the Pacific Ocean.[note 3][note 4] Five territories (American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the United States Virgin Islands) are permanently inhabited, unincorporated territories; the other nine are small islands, atolls, and reefs with no native (or permanent) population. Of the nine, only one is classified as an incorporated territory (Palmyra Atoll). Two additional territories (Bajo Nuevo Bank and Serranilla Bank) are claimed by the U.S. but administered by Colombia.[7][12][13] Historically, territories were created to administer newly acquired land, and most eventually attained statehood.[14][15] The most recent territory to become a U.S. state was Hawaii on August 21, 1959.[16]

Politically and economically, the territories are underdeveloped. Residents of the U.S. territories cannot vote in United States presidential elections, and they have only non-voting representation in the U.S. Congress.[7] According to 2012 data, territorial telecommunications and other infrastructure are generally inferior to that of the continental U.S. and Hawaii.[17] Poverty rates are higher in the territories than in the states.[18][19]

Organized vs. unorganized territories

Summarize

Perspective

Definitions

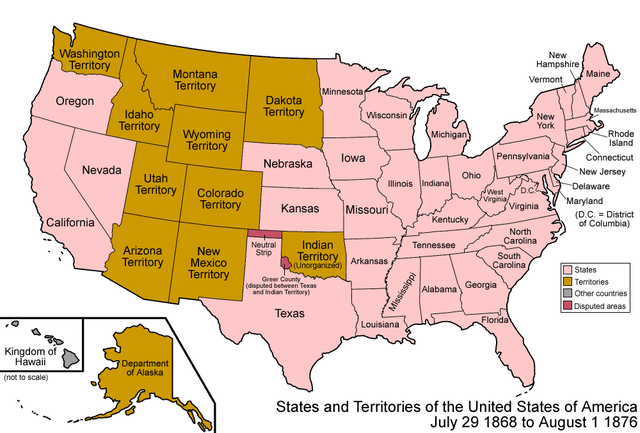

Organized territories are lands under federal sovereignty (but not part of any state or the federal district) that were given a measure of self-governance by Congress through an organic act subject to the Congress's plenary powers under the Territorial Clause of the Constitution's Article Four, section 3.[20] The term unorganized historically had two applications. One application was to a newly acquired region not yet constituted as an organized incorporated territory (e.g. the Louisiana Purchase prior to the establishment of Orleans Territory and the District of Louisiana). The other was to a region that was previously part of an organized incorporated territory, but subsequently left "unorganized" after part of it had been organized and had achieved the requirements for statehood. (E.g., a large portion of Missouri Territory became unorganized territory for several years after its southeastern section became the state of Missouri.)

Historical practice

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 created the Kansas and Nebraska Territories, bringing organized government to the region once again. The creation of Kansas and Nebraska left the Indian Territory as the only unorganized territory in the Great Plains. In 1858, the western part of the Minnesota Territory became unorganized when it was not included in the new state of Minnesota; this area was organized in 1861 as part of the Dakota Territory. In 1890, the western half of the Indian Territory was organized as Oklahoma Territory. The eastern half remained unorganized until 1907, when it was joined with Oklahoma Territory to form the State of Oklahoma. Additionally, the Department of Alaska was unorganized from its acquisition in 1867 from Russia until organized as the District of Alaska in 1884; it was organized as Alaska Territory in 1912. Hawaii was also unorganized from the time of its annexation by the U.S. in 1898 until organized as Hawaii Territory in 1900.

Regions that have been admitted as states under the United States Constitution in addition to the original thirteen were, most often, prior to admission, territories or parts of territories of this kind. As the United States grew, the most populous parts of the organized territory would achieve statehood. Some territories existed only a short time before becoming states, while others remained territories for decades. The shortest-lived was Alabama Territory at two years, while New Mexico Territory and Hawaii Territory both lasted more than 50 years.

Of the 50 states, 31 were once part of an organized, incorporated U.S. territory. In addition to the original 13, six subsequent states never were: Kentucky, Maine, and West Virginia were each separated from an existing state;[21] Texas and Vermont were both sovereign states (de facto sovereignty for Vermont, as the region was claimed by New York) when they entered the Union; and California was part of unorganized land ceded to the United States by Mexico in 1848 at the end of the Mexican–American War.

Federal administration of current territories

All of the five major U.S. territories are permanently inhabited and have locally elected territorial legislatures and executives and some degree of political autonomy. Four of the five are organized but American Samoa is technically unorganized. All of the U.S. territories without permanent non-military populations are unorganized.

The Office of Insular Affairs coordinates federal administration of the U.S. territories and freely associated states, except for Puerto Rico.[22]

On March 3, 1849, the last day of the 30th Congress, a bill was passed to create the U.S. Department of the Interior to take charge of the internal affairs of United States territory. The Interior Department has a wide range of responsibilities (which include the regulation of territorial governments, the basic responsibilities for public lands, and other various duties).

In contrast to similarly named Departments in other countries, the United States Department of the Interior is not responsible for local government or for civil administration except in the cases of Indian reservations, through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), and island dependencies administered by the Office of Insular Affairs.

Permanently inhabited territories

Summarize

Perspective

The U.S. has five permanently inhabited territories: Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands in the Caribbean Sea, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands in the North Pacific Ocean, and American Samoa in the South Pacific Ocean.[note 5] American Samoa is in the Southern Hemisphere, while the other four are in the Northern Hemisphere.[23] In 2020, their combined population was about 3.62 million, over 90% of which is accounted for by Puerto Rico alone.[24][25]

People born in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands acquire U.S. citizenship by birth, and foreign nationals residing there may apply for U.S. citizenship by naturalization.[26][27][28][note 6] People born in American Samoa acquire U.S. nationality but not U.S. citizenship by birth if they do not have a U.S. citizen parent.[note 7] U.S. nationals without U.S. citizenship may hold U.S. passports and reside in any part of the United States without restriction.[32] However, to become U.S. citizens they must apply for naturalization, like foreigners, and may only do so while residing in parts of the United States other than American Samoa.[33][note 8] Foreign nationals residing in American Samoa cannot apply for U.S. citizenship or U.S. nationality at all.[35][36]

Each territory is self-governing[8] with three branches of government, including a locally elected governor and a territorial legislature.[7] Each territory elects a non-voting member (a non-voting resident commissioner in the case of Puerto Rico) to the U.S. House of Representatives.[7][37][38] Although they cannot vote on the passage of legislation, they can introduce legislation, have floor privileges to address the house, be members of and vote in committees, are assigned offices and staff funding, and may nominate constituents from their territories to the Army, Naval, Air Force and Merchant Marine academies.[39]

As of the 118th Congress, the territories are represented by Aumua Amata Radewagen (R) of American Samoa, James Moylan (R) of Guam, Gregorio Sablan (D) of Northern Mariana Islands, Jenniffer González-Colón (R-PNP) of Puerto Rico and Stacey Plaskett (D) of U.S. Virgin Islands.[40] The District of Columbia's delegate is Eleanor Holmes Norton (D); like the district, the territories have no vote in Congress and no representation in the Senate.[41][42] Additionally, the Cherokee Nation has delegate-elect Kimberly Teehee, who has not been seated by Congress.

Every four years, U.S. political parties nominate presidential candidates at conventions which include delegates from the territories.[43] U.S. citizens living in the territories can vote for presidential candidates in these primary elections but not in the general election.[7][41]

The territorial capitals are Pago Pago (American Samoa), Hagåtña (Guam), Saipan (Northern Mariana Islands), San Juan (Puerto Rico) and Charlotte Amalie (U.S. Virgin Islands).[44][45][46][47][48][49][50] Their governors are Pula Nikolao Pula (American Samoa), Lou Leon Guerrero (Guam), Arnold Palacios (Northern Mariana Islands), Jenniffer González-Colón (Puerto Rico) and Albert Bryan Jr. (U.S. Virgin Islands).

Among the inhabited territories, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is available only in the Northern Mariana Islands;[note 9] however, in 2019 a U.S. judge ruled that the federal government's denial of SSI benefits to residents of Puerto Rico is unconstitutional.[51] This ruling was later overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court, allowing for the exclusion of territories from such programs.[52] In the decision, the court explained that the exemption of island residents from most federal income taxes provides a "rational basis" for their exclusion from eligibility for SSI payments.[53]

American Samoa is the only U.S. territory with its own immigration system (a system separate from the United States immigration system).[54][55] American Samoa also has a communal land system in which 90% of the land is communally owned; ownership is based on Samoan ancestry.[56]

| Name (abbreviation) | Location | Area | Population (2020)[24][25] |

Capital | Largest town | Status | Acquired |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polynesia (South Pacific) | 197.1 km2 (76 sq mi) | 49,710 | Pago Pago | Tafuna | Unincorporated, unorganized[note 10] | April 17, 1900 | |

| Micronesia (North Pacific) | 543 km2 (210 sq mi) | 153,836 | Hagåtña | Dededo | Unincorporated, organized | April 11, 1899 | |

| Micronesia (North Pacific) | 463.63 km2 (179 sq mi) | 47,329 | Saipan[note 11] | Saipan[note 12] | Unincorporated, organized (Commonwealth) | November 4, 1986[note 13][58][57] | |

| Caribbean (North Atlantic) | 9,104 km2 (3,515 sq mi) | 3,285,874 | San Juan | San Juan | Unincorporated, organized (Commonwealth) | April 11, 1899[59] | |

| Caribbean (North Atlantic) | 346.36 km2 (134 sq mi) | 87,146 | Charlotte Amalie | Charlotte Amalie | Unincorporated, organized | March 31, 1917[60] | |

History

- American Samoa: territory since 1900; after the end of the Second Samoan Civil War, the Samoan Islands were divided into two regions. The U.S. took control of the eastern half of the islands.[61][23] In 1900, the Treaty of Cession of Tutuila took effect.[62] The Manuʻa Islands became part of American Samoa in 1904, and Swains Island became part of American Samoa in 1925.[62] Congress ratified American Samoa's treaties in 1929.[62] For 51 years, the U.S. Navy controlled the territory.[34] American Samoa is locally self-governing under a constitution last revised in 1967.[23][note 14] The first elected governor of American Samoa was in 1977, and the first non-voting member of Congress was in 1981.[34] By jus soli, people born in American Samoa are U.S. nationals, but not U.S. citizens.[26][23] American Samoa is technically unorganized,[23] and its main island is Tutuila.[23]

- Guam: territory since 1899, acquired at the end of the Spanish–American War.[64] Guam is the home of Naval Base Guam and Andersen Air Force Base. It was organized under the Guam Organic Act of 1950, which granted U.S. citizenship to Guamanians and gave Guam a local government.[64] In 1968, the act was amended to permit the election of a governor.[64]

- Northern Mariana Islands: A commonwealth since 1986,[58][57] the Northern Mariana Islands together with Guam were part of the Spanish Empire until 1899 when the Northern Marianas were sold to the German Empire after the Spanish–American War.[65] Beginning in 1919, they were administered by Japan as a League of Nations mandate until the islands were captured by the United States in the Battle of Saipan and Battle of Tinian (June–August 1944) and the surrender of Aguiguan (September 1945) during World War II.[65] They became part of the United Nations Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) in 1947, administered by the United States as U.N. trustee.[65][57] The other constituents of the TTPI were Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Marshall Islands.[66] Following failed efforts in the 1950s and 1960s to reunify Guam and the Northern Marianas,[67] a covenant to establish the Northern Mariana Islands as a commonwealth in political union with the United States was negotiated by representatives of both political bodies; it was approved by Northern Mariana Islands voters in 1975, and came into force on March 24, 1976.[65][46] In accordance with the covenant, the Northern Mariana Islands constitution partially took effect on January 9, 1978, and became fully effective on November 4, 1986.[46] In 1986, the Northern Mariana Islands formally left U.N. trusteeship.[58] The abbreviations "CNMI" and "NMI" are both used in the commonwealth. Most residents in the Northern Mariana Islands live on Saipan, the main island.[46]

- Puerto Rico: unincorporated territory since 1899;[59] Puerto Rico was acquired at the end of the Spanish–American War,[68] and has been a U.S. commonwealth since 1952.[69] Since 1917, Puerto Ricans have been granted U.S. citizenship.[70] Puerto Rico was organized under the Puerto Rico Federal Relations Act of 1950 (Public Law 600). In November 2008, a U.S. District Court judge ruled that a series of Congressional actions have had the cumulative effect of changing Puerto Rico's status from unincorporated to incorporated.[71] The issue is proceeding through the courts, however,[72] and the U.S. government still refers to Puerto Rico as unincorporated. A Puerto Rican attorney has called the island "semi-sovereign".[73] Puerto Rico has a statehood movement, whose goal is to make the territory the 51st state.[42][74] See also Political status of Puerto Rico.

- U.S. Virgin Islands: purchased by the U.S. from Denmark in 1917 and organized under the Revised Organic Act of the Virgin Islands in 1954. U.S. citizenship was granted in 1927.[75] The main islands are Saint Thomas, Saint John and Saint Croix.[48]

Statistics

Except for Guam, the inhabited territories lost population in 2020. Although the territories have higher poverty rates than the mainland U.S., they have high Human Development Indexes. Four of the five territories have another official language, in addition to English.[76][77]

| Territory | Official language(s)[76][77] | Pop. change (2021 est.) [44][45][46][47][48] |

Poverty rate[78][79] | Life expectancy in 2018–2020 (years) [80][44][45][46][47][48] |

HDI[81][82] | GDP ($)[83] | Traffic flow | Time zone | Area code (+1) | Largest ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Samoa | Samoan, English | −2.1% | 65% (2017)[note 15] | 74.8 | 0.827 | $0.636 billion | Right | Samoan Time (UTC−11) | 684 | Pacific Islander (Samoan)[85] |

| Guam | English, Chamorro | +0.18% | 22.9% (2009) | 79.86 | 0.901 | $5.92 billion | Right | Chamorro Time (UTC+10) | 671 | Pacific Islander (Chamorro)[86] |

| Northern Mariana Islands | English, Chamorro, Carolinian | −0.36% | 52.3% (2009) | 76.1 | 0.875 | $1.323 billion | Right | Chamorro Time | 670 | Asian[87] |

| Puerto Rico | Spanish, English | −1.46% | 43.1% (2018) | 79.78 | 0.845 | $104.98 billion | Right | Atlantic Time (UTC−4) | 787, 939 | Hispanic/ |

| U.S. Virgin Islands | English | −0.42% | 22.4% (2009) | 79.57 | 0.894 | $3.85 billion | Left | Atlantic Time | 340 | African-American[89] |

The territories do not have administrative counties.[note 17] The U.S. Census Bureau counts Puerto Rico's 78 municipalities, the U.S. Virgin Islands' three main islands, all of Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands' four municipalities, and American Samoa's three districts and two atolls as county equivalents.[90][91] The Census Bureau also counts each of the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands as county equivalents.[90][91][92]

For statistical purposes, the U.S. Census Bureau has a defined area called the "Island Areas" which consists of American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands (every major territory except Puerto Rico).[93][94][95] The U.S. Census Bureau often treats Puerto Rico as its own entity or groups it with the states and D.C. (for example, Puerto Rico has a QuickFacts page just like the states and D.C.)[96] Puerto Rico data is collected annually in American Community Survey estimates (just like the states), but data for the other territories is collected only once every ten years.[97]

Governments and legislatures

The five major inhabited territories contain the following governments and legislatures:

| Government | Legislature | Legislature form |

|---|---|---|

| Government of American Samoa | American Samoa Fono | Bicameral |

| Government of Guam | Legislature of Guam | Unicameral |

| Government of the Northern Mariana Islands | N. Mariana Islands Commonwealth Legislature | Bicameral |

| Government of Puerto Rico | Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico | Bicameral |

| Government of the U.S. Virgin Islands | Legislature of the Virgin Islands | Unicameral |

Political party status

The following is the political party status of the governments of the U.S. territories following completion of the 2024 United States elections. Instances where local and national party affiliation differs, the national affiliation is listed second. Guam and the U.S. Virgin Islands have unicameral territorial legislatures.

| Territory | Governor | Territory Senate | Territory House | U.S. House of Representatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Samoa | Non-Partisan Republican |

Non-Partisan | Non-Partisan | Republican |

| Guam | Democratic | Republican 9–6 | Republican | |

| Northern Mariana Islands | Republican | Republican 4–2–3[a] | Independent 13–4–3[b] | Republican |

| Puerto Rico | New Progressive Republican |

New Progressive 19–5–2–1–1[c] |

New Progressive 36–13–3–1[d] |

Popular Democratic Democratic |

| U.S. Virgin Islands | Democratic | Democratic 12–3[e] | Democratic | |

Courts

Each of the five major territories has its own local court system:

- High Court of American Samoa

- Supreme Court of Guam

- Supreme Court of the Northern Mariana Islands

- Supreme Court of Puerto Rico

- Supreme Court of the Virgin Islands

Of the five major territories, only Puerto Rico has an Article III federal district court (i.e., equivalent to the courts in the fifty states); it became an Article III court in 1966.[98] This means that, unlike other U.S. territories, federal judges in Puerto Rico have life tenure.[98] Federal courts in Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and the U.S. Virgin Islands are Article IV territorial courts.[98][99] The following is a list of federal territorial courts, plus Puerto Rico's court:

- District Court of Guam (Ninth Circuit)

- District Court for the Northern Mariana Islands (Ninth Circuit)

- District Court for the District of Puerto Rico (not a territorial court) (First Circuit)

- District Court of the Virgin Islands (Third Circuit)

American Samoa does not have a federal territorial court, and so federal matters in American Samoa are sent to either the District court of Hawaii or the District court of the District of Columbia.[100] American Samoa is the only permanently inhabited region of the United States with no federal court.[100]

Demographics

While the U.S. mainland is majority non-Hispanic White,[101] this is not the case for the U.S. territories. In 2010, American Samoa's population was 92.6% Pacific Islander (including 88.9% Samoan); Guam's population was 49.3% Pacific Islander (including 37.3% Chamorro) and 32.2% Asian (including 26.3% Filipino); the population of the Northern Mariana Islands was 34.9% Pacific Islander and 49.9% Asian; and the population of the U.S. Virgin Islands was 76.0% African American.[102] In 2019, Puerto Rico's population was 98.9% Hispanic or Latino, 67.4% white, and 0.8% non-Hispanic white.[103]

Throughout the 2010s, the U.S. territories (overall) lost population. The combined population of the five inhabited territories was 4,100,594 in 2010,[93] and 3,569,284 in 2020.[44][45][46][47][48][103]

The U.S. territories have high religiosity rates—American Samoa has the highest religiosity rate in the United States (99.3% religious and 98.3% Christian).[44]

Economies

The economies of the U.S. territories vary from Puerto Rico, which has a GDP of $104.989 billion in 2019, to American Samoa, which has a GDP of $636 million in 2018.[83] In 2018, Puerto Rico exported about $18 billion in goods, with the Netherlands as the largest destination.[104]

Guam's GDP shrank by 0.3% in 2018, the GDP of the Northern Mariana Islands shrank by 19.6% in 2018, Puerto Rico's GDP grew by 1.18% in 2019, and the U.S. Virgin Islands' GDP grew by 1.5% in 2018.[105][106][47][107][108] In 2017, American Samoa's GDP shrank by 5.8%, but then grew by 2.2% in 2018.[109]

American Samoa has the lowest per capita income in the United States—it has a per capita income comparable to that of Botswana.[110] In 2010, American Samoa's per capita income was $6,311.[111] As of 2010, the Manuʻa District in American Samoa had a per capita income of $5,441, the lowest of any county or county-equivalent in the United States.[111] In 2018, Puerto Rico had a median household income of $20,166 (lower than the median household income of any state).[103][112] Also in 2018, Comerío Municipality, Puerto Rico had a median household income of $12,812 (the lowest median household income of any populated county or county-equivalent in the U.S.)[113] Guam has much higher incomes (Guam had a median household income of $48,274 in 2010.)[114]

Minor Outlying Islands

Summarize

Perspective

The United States Minor Outlying Islands are small uninhabited islands, atolls, and reefs. Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Midway Atoll, Palmyra Atoll, and Wake Island are in the Pacific Ocean while Navassa Island is in the Caribbean Sea. The additional claimed territories of Bajo Nuevo Bank and Serranilla Bank are also located in the Caribbean Sea. Palmyra Atoll (formally known as the United States Territory of Palmyra Island)[115] is the only incorporated territory, a status it has maintained since Hawaii became a state in 1959.[10] All are uninhabited except for Midway Atoll, whose approximately 40 inhabitants (as of 2004) were employees of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and their services provider;[116] Palmyra Atoll, whose population varies from four to 20 Nature Conservancy and Fish and Wildlife staff and researchers;[117] and Wake Island, which has a population of about 100 military personnel and civilian employees.[118] The two-letter abbreviation for the islands collectively is "UM".[92]

The status of several islands is disputed. Navassa Island is disputed by Haiti,[119] Wake Island is disputed by the Marshall Islands,[118] Swains Island (a part of American Samoa) is disputed by Tokelau,[120][44] and Bajo Nuevo Bank and Serranilla Bank are both administered by Colombia, whose claim is disputed by the U.S. and Jamaica.[7][121]

| Name | Location | Area | Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker Island[a] | Polynesia (North Pacific) | 2.1 km2 (0.81 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on October 28, 1856.[122][123] Annexed on May 13, 1936, and placed under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of the Interior.[124] |

| Howland Island[a] | Polynesia (North Pacific) | 4.5 km2 (1.7 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on December 3, 1858.[122][123] Annexed on May 13, 1936, and placed under the jurisdiction of the Interior Department.[124] |

| Jarvis Island[a] | Polynesia (South Pacific) | 4.75 km2 (1.83 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on October 28, 1856.[122][123] Annexed on May 13, 1936, and placed under the jurisdiction of the Interior Department.[124] |

| Johnston Atoll[a] | Polynesia (North Pacific) | 2.67 km2 (1.03 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Last used by the U.S. Department of Defense in 2004. |

| Kingman Reef[a] | Polynesia (North Pacific) | 18 km2 (6.9 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on February 8, 1860.[122][123] Annexed on May 10, 1922, and placed under the jurisdiction of the Navy Department on December 29, 1934.[125] |

| Midway Atoll | Polynesia (North Pacific) | 6.2 km2 (2.4 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Territory since 1859; primarily a National Wildlife Refuge and previously under the jurisdiction of the Navy Department. |

| Navassa Island | Caribbean (North Atlantic) | 5.4 km2 (2.1 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Territory since 1857; also claimed by Haiti.[119] |

| Palmyra Atoll | Polynesia (North Pacific) | 12 km2 (5 sq mi) | Incorporated, unorganized | Partially privately owned by The Nature Conservancy, with much of the rest owned by the federal government and managed by the Fish and Wildlife Service.[126][127] It is an archipelago of about fifty small islands with a land area of about 1.56 sq mi (4.0 km2), about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) south of Oahu. The atoll was acquired through the annexation of the Republic of Hawaii in 1898. When the Territory of Hawaii was incorporated on April 30, 1900, Palmyra Atoll was incorporated as part of that territory. When Hawaii became a state in 1959, however, an act of Congress excluded the atoll from the state. Palmyra remained an incorporated territory, but received no new, organized government.[10] U.S. sovereignty over Palmyra Atoll (and Hawaii) is disputed by the Hawaiian sovereignty movement.[128][129] |

| Wake Island[a] | Micronesia (North Pacific) | 7.4 km2 (2.9 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Territory since 1898; host to the Wake Island Airfield, administered by the U.S. Air Force. Wake Island is claimed by the Marshall Islands.[118] |

- These six unincorporated territories and Palmyra Atoll make up the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument.

Claimed territories

The following two territories are claimed by multiple countries (including the United States)[7] and are not included in ISO 3166-2:UM. However, they are sometimes grouped with the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands. According to the GAO, "the United States conducts maritime law enforcement operations in and around Serranilla Bank and Bajo Nuevo [Bank] consistent with U.S. sovereignty claims."[7]

| Name | Location | Area | Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bajo Nuevo Bank | Caribbean (North Atlantic) | 110 km2 (42 sq mi) | Claimed | Controlled by Colombia. Claimed by the United States (under the Guano Islands Act) and Jamaica. A claim by Nicaragua was resolved in 2012 in favor of Colombia by the International Court of Justice, although the U.S. was not a party to that case and does not recognize the ICJ's compulsory jurisdiction.[130] |

| Serranilla Bank | Caribbean (North Atlantic) | 350 km2 (140 sq mi) | Claimed | Controlled by Colombia; site of a naval garrison. Claimed by the United States (since 1879 under the Guano Islands Act) and Jamaica. A claim by Nicaragua was resolved in 2012 in favor of Colombia by the International Court of Justice, although the United States was not a party to that case and does not recognize the ICJ's compulsory jurisdiction.[130] A claim by Honduras was settled in a 1986 treaty over maritime boundaries with Colombia.[131]

|

Incorporated vs. unincorporated territories

Summarize

Perspective

Pursuant to a series of Supreme Court rulings, Congress decides whether a territory is incorporated or unincorporated. The U.S. Constitution applies to each incorporated territory (including its local government and inhabitants) as it applies to the local governments and residents of a state. The singular incorporated territory (also known as a Territory, distinct from territory) of the U.S., Palmyra Atoll, is an insular part of the U.S. (neither a part of one of the several States nor a Federal district), but is not a possession.[132]

In unincorporated territories, "fundamental rights apply as a matter of law, but other constitutional rights are not available", raising concerns about how citizens in these territories can influence politics in the United States.[133] Selected constitutional provisions apply, depending on congressional acts and judicial rulings according to U.S. constitutional practice, local tradition, and law.[citation needed] As a result, these territories are often considered colonies of the United States.[134][135]

All modern inhabited territories under the control of the federal government can be considered as part of the "United States" for purposes of law as defined in specific legislation.[136][137] However, the judicial term "unincorporated" was coined to legitimize the late-19th-century territorial acquisitions without citizenship and their administration without constitutional protections temporarily until Congress made other provisions. The case law allowed Congress to impose discriminatory tax regimes with the effect of a protective tariff upon territorial regions which were not domestic states.[138] In 2022, the United States Supreme Court in United States v. Vaello Madero held that the territorial clause of the constitution allowed wide congressional latitude in mandating "reasonable" tax and benefit schemes in Puerto Rico and the other territories, which are different from the states, but did not address the incorporated/unincorporated distinction. In a concurrence with the court's overall ruling on the propriety of the differential tax structures, one of the justices opined that it was time to overrule the doctrine of unincorporated territories, as wrongly decided and founded in racism; the dissent agreed with this view.[139][140]

Insular Cases

The U.S. Supreme Court, in its 1901–1905 Insular Cases opinions, ruled that the Constitution extended ex proprio vigore (i.e., of its own force) to the continental territories. The Court also established the doctrine of territorial incorporation, in which the Constitution applies fully to incorporated territories (such as the then-territories of Alaska and Hawaii) and partially in the unincorporated territories of Guam, Puerto Rico, and, at the time, the Philippines (which is no longer a U.S. territory).[141][142][143]

In the 1901 Supreme Court case Downes v. Bidwell, the Court said that the U.S. Constitution did not fully apply in unincorporated territories because they were inhabited by "alien races".[144][145]

The U.S. had no unincorporated territories (also known as overseas possessions or insular areas) until 1856. Congress enacted the Guano Islands Act that year, authorizing the president to take possession of unclaimed islands to mine guano. The U.S. has taken control of (and claimed rights on) many islands and atolls, especially in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, under this law; most have been abandoned. It also has acquired territories since 1856 under other circumstances, such as under the Treaty of Paris (1898) which ended the Spanish–American War. The Supreme Court considered the constitutional position of these unincorporated territories in 1922 in Balzac v. People of Porto Rico, and said the following about a U.S. court in Puerto Rico:

The United States District Court is not a true United States court established under article 3 of the Constitution to administer the judicial power of the United States ... It is created ... by the sovereign congressional faculty, granted under article 4, 3, of that instrument, of making all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory belonging to the United States. The resemblance of its jurisdiction to that of true United States courts, in offering an opportunity to nonresidents of resorting to a tribunal not subject to local influence, does not change its character as a mere territorial court.[146]: 312

In Glidden Company v. Zdanok, the Court cited Balzac and said about courts in unincorporated territories: "Upon like considerations, Article III has been viewed as inapplicable to courts created in unincorporated territories outside the mainland ... and to the consular courts established by concessions from foreign countries".[147]: 547 The judiciary determined that incorporation involves express declaration or an implication strong enough to exclude any other view, raising questions about Puerto Rico's status.[148]

In 1966, Congress made the United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico an Article III district court. This (the only district court in a U.S. territory) sets Puerto Rico apart judicially from the other unincorporated territories, and U.S. district judge Gustavo Gelpí has expressed the opinion that Puerto Rico is no longer unincorporated:

The court ... today holds that in the particular case of Puerto Rico, a monumental constitutional evolution based on continued and repeated congressional annexation has taken place. Given the same, the territory has evolved from an unincorporated to an incorporated one. Congress today, thus, must afford Puerto Rico and the 4,000,000 United States citizens residing therein all constitutional guarantees. To hold otherwise, would amount to the court blindfolding itself to continue permitting Congress per secula seculorum to switch on and off the Constitution.[149]

In Balzac, the Court defined "implied":[146]: 306

Had Congress intended to take the important step of changing the treaty status of Puerto Rico by incorporating it into the Union, it is reasonable to suppose that it would have done so by the plain declaration, and would not have left it to mere inference. Before the question became acute at the close of the Spanish War, the distinction between acquisition and incorporation was not regarded as important, or at least it was not fully understood and had not aroused great controversy. Before that, the purpose of Congress might well be a matter of mere inference from various legislative acts; but in these latter days, incorporation is not to be assumed without express declaration, or an implication so strong as to exclude any other view.

On June 5, 2015, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled 3–0 in Tuaua v. United States to deny birthright citizenship to American Samoans, ruling that the guarantee of such citizenship to citizens in the Fourteenth Amendment does not apply to unincorporated U.S. territories. In 2016 the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the appellate court's decision.[150]

In 2018, the United States Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit upheld the District Court decision in Segovia v. United States, which ruled that former Illinois residents living in Puerto Rico, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands did not qualify to cast overseas ballots according to their last registered address on the U.S. mainland.[151] (Residents of the Northern Marianas and American Samoa, however, were still allowed to cast such ballots.) In October 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the 7th Circuit's decision.

On June 15, 2021, the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit ruled 2–1 in Fitisemanu v. United States to deny birthright citizenship to American Samoans and not to overrule the Insular Cases. The court cited Downes and ruled that "neither constitutional text nor Supreme Court precedent" demands that American Samoans should be given automatic birthright citizenship.[152] The case was denied certiorari by the U.S. Supreme Court.[153] On April 21, 2022, in the case United States v. Vaello Madero, Justice Gorsuch urged the Supreme Court to overrule the Insular Cases when possible as they "rest on a rotten foundation" and called the cases "shameful".[154][155][156]

In analyzing the Insular Cases, Christina Duffy Ponsa (Juris Doctor, Yale Law School, 1998; former law clerk for Justice Stephen Breyer[157]) wrote in The New York Times: "To be an unincorporated territory is to be caught in limbo: although unquestionably subject to American sovereignty, they are considered part of the United States for certain purposes but not others. Whether they are part of the United States for purposes of the Citizenship Clause remains unresolved. "[4]

Supreme Court decisions about current territories

The 2016 Supreme Court case Puerto Rico v. Sanchez Valle ruled that territories do not have their own sovereignty.[2] That year, the Supreme Court declined to rule on a lower-court ruling in Tuaua v. United States that American Samoans are not U.S. citizens at birth.[29][30]

The Supreme Court ruled in 2022 in United States v. Vaello-Madero that Congress is not required to extend all benefits to Puerto Ricans, and that the exclusion of Puerto Ricans from the Supplemental Security Income program was constitutional.[158]

Supreme Court decisions about former territories

In Rassmussen v. U.S., the Supreme Court quoted from Article III of the 1867 treaty for the purchase of Alaska:

"The inhabitants of the ceded territory ... shall be admitted to the enjoyment of all the rights, advantages, and immunities of citizens of the United States ..." This declaration, although somewhat changed in phraseology, is the equivalent ... of the formula, employed from the beginning to express the purpose to incorporate acquired territory into the United States, especially in the absence of other provisions showing an intention to the contrary.[159]: 522

The act of incorporation affects the people of the territory more than the territory itself by extending the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Constitution to them, such as its extension to Puerto Rico in 1947; however, Puerto Rico remains unincorporated.[148]

Alaska Territory

Rassmussen arose from a criminal conviction by a six-person jury in Alaska under federal law. The court held that Alaska had been incorporated into the U.S. in the treaty of cession with Russia,[160] and the congressional implication was strong enough to exclude any other view:[159]: 523

That Congress, shortly following the adoption of the treaty with Russia, clearly contemplated the incorporation of Alaska into the United States as a part thereof, we think plainly results from the act of July 20, 1868, concerning internal revenue taxation ... and the act of July 27, 1868 ... extending the laws of the United States relating to customs, commerce, and navigation over Alaska, and establishing a collection district therein ... And this is fortified by subsequent action of Congress, which it is unnecessary to refer to.

Concurring justice Henry Brown agreed:[159]: 533–34

Apparently, acceptance of the territory is insufficient in the opinion of the court in this case, since the result that Alaska is incorporated into the United States is reached, not through the treaty with Russia, or through the establishment of a civil government there, but from the act ... extending the laws of the United States relating to the customs, commerce, and navigation over Alaska, and establishing a collection district there. Certain other acts are cited, notably the judiciary act ... making it the duty of this court to assign ... the several territories of the United States to particular Circuits.

Florida Territory

In Dorr v. U.S., the court quoted Chief Justice John Marshall from an earlier case:[161]: 141–2

The 6th article of the treaty of cession contains the following provision: "The inhabitants of the territories which His Catholic Majesty cedes the United States by this treaty shall be incorporated in the Union of the United States as soon as may be consistent with the principles of the Federal Constitution and admitted to the enjoyment of the privileges, rights, and immunities of the citizens of the United States ..." This treaty is the law of the land and admits the inhabitants of Florida to the enjoyment of the privileges, rights, and immunities of the citizens of the United States. It is unnecessary to inquire whether this is not their condition, independent of stipulation. They do not, however, participate in political power; they do not share in the government till Florida shall become a state. In the meantime Florida continues to be a territory of the United States, governed by virtue of that clause in the Constitution which empowers Congress "to make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory or other property belonging to the United States".

In Downes v. Bidwell, the court said: "The same construction was adhered to in the treaty with Spain for the purchase of Florida ... the 6th article of which provided that the inhabitants should 'be incorporated into the Union of the United States, as soon as may be consistent with the principles of the Federal Constitution'."[162]: 256

Southwest Territory

Justice Brown first mentioned incorporation in Downes:[162]: 321–22

In view of this it cannot, it seems to me, be doubted that the United States continued to be composed of states and territories, all forming an integral part thereof and incorporated therein, as was the case prior to the adoption of the Constitution. Subsequently, the territory now embraced in the state of Tennessee was ceded to the United States by the state of North Carolina. To ensure the rights of the native inhabitants, it was expressly stipulated that the inhabitants of the ceded territory should enjoy all the rights, privileges, benefits, and advantages set forth in the ordinance of the late Congress for the government of the western territory of the United States.

Louisiana Territory

In Downes, the court said:

Owing to a new war between England and France being upon the point of breaking out, there was need for haste in the negotiations, and Mr. Livingston took the responsibility of disobeying his (Mr. Jefferson's) instructions, and, probably owing to the insistence of Bonaparte, consented to the 3d article of the treaty (with France to acquire the territory of Louisiana), which provided that "the inhabitants of the ceded territory shall be incorporated in the Union of the United States, and admitted as soon as possible, according to the principles of the Federal Constitution, to the enjoyment of all the rights, advantages, and immunities of citizens of the United States; and in the meantime they shall be maintained and protected in the free enjoyment of their liberty, property, and the religion which they profess." [8 Stat. at L. 202.] This evidently committed the government to the ultimate, but not to the immediate, admission of Louisiana as a state ...[162]: 252

Modern Puerto Rico

Scholars agreed as of 2009 in the Boston College Law Review, "Regardless of how Puerto Rico looked in 1901 when the Insular Cases were decided, or in 1922, today, Puerto Rico seems to be the paradigm of an incorporated territory as modern jurisprudence understands that legal term of art".[163] In November 2008, a district court judge ruled that a sequence of prior Congressional actions had the cumulative effect of changing Puerto Rico's status to incorporated.[164] However, in 2022, the United States Supreme Court held that the territorial clause of the US constitution allows wide congressional latitude in mandating "reasonable" tax and benefit schemes in Puerto Rico and the other territories that are different from the states, but the Court did not address the incorporated/unincorporated distinction.[139] As a result, the status quo remains, so the US government still defines the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico as a US unincorporated territory.

Former unincorporated territories and administered areas

Former unincorporated territories

- Swan Islands (1863–1972): claimed under the Guano Islands Act; sovereignty ceded to Honduras in a 1972 treaty.[165]

- Philippines: military government, 1898-1899; insular government, 1899–1935; commonwealth government, 1935–1942 and 1945–1946 (islands under Japanese occupation, 1942–1945 and puppet state, 1943–1945); granted independence on July 4, 1946, by the Treaty of Manila.[166][167][168][169][170]

- Puerto Rico: military government, 1899–1900; insular government, 1900–1952; became a commonwealth on July 25, 1952.

- Naval Government of Guam (1899–1950): island under Japanese occupation between 1941 and 1944; territory organized and civil government established by the Guam Organic Act of 1950.

- Republic of Hawaii (1898–1900): became the Territory of Hawaii after it was organized and incorporated by the Hawaiian Organic Act on April 30, 1900.[171]

Former U.S.-administered areas

- American concession of Shanghai (1848–1863): a former enclave in Shanghai, China.

- American concession of Tianjin (1860–1901): a former territorial concession in the Chinese city of Tientsin de facto occupied by the United States.

- Panama Canal (1903–1999): Canal Zone abolished on October 1, 1979, after the signing of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties in 1977. The U.S. retained a military base on the former Canal Zone until December 31, 1999, when joint U.S.-Panama control of the Panama Canal ended.

- Corn Islands (1914–1971): leased for 99 years under the Bryan–Chamorro Treaty, but returned to Nicaragua after the treaty was annulled in 1970.

- Canton and Enderbury Islands (1939–1979): condominium jointly administered by the United States and the United Kingdom.

- Nanpō Islands and Marcus Island (1945–1968): occupied after World War II and returned to Japan by mutual agreement.

- Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (1947–1986): U.N. trust territory administered by the U.S.; included the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau, which are sovereign states (that have entered into a Compact of Free Association with the U.S.), along with the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

- Ryukyu Islands and Daitō Islands (1950–1972): returned to Japan in an agreement.[172]

Former U.S. military occupations

- First occupation of Cuba (1898–1902): sovereignty over the island relinquished by Spain on April 11, 1899, when the Treaty of Paris took effect. Cuban independence was recognized on May 20, 1902.[173]

- Military occupation of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam during the Spanish–American War (1898–1899): territories annexed on April 11, 1899, when the Treaty of Paris took effect.

- Second occupation of Cuba (1906–1909)

- United States occupation of Nicaragua (1912–1933)

- United States occupation of Veracruz (1914)

- United States occupation of Haiti (1915–1934)

- United States occupation of the Dominican Republic (1916–1924)

- Sugar Intervention on Cuba (1917–1922)

- Participation in the Occupation of Austria-Hungary (1918–1919)

- Participation in the Occupation of the Rhineland (1918–1921)

- Participation in the Occupation of Constantinople (1918–1923)

- Occupation of Greenland in World War II (1941–1945)[174]

- Occupation of Iceland in World War II (1941–1946):[174] military base retained until 2006.

- Allied Military Government for Occupied Territories, in Allied-controlled sections of Italy from the July 1943 invasion of Sicily until the September armistice with Italy. AMGOT continued in newly liberated areas of Italy until the end of the war, and also existed in France.[citation needed]

- Occupation of Clipperton Island in World War II (1944–1945): occupied territory, returned to France on October 23, 1945.

- United States Army Military Government in Korea: occupation south of the 38th parallel from 1945 to 1948.

- American zones of Allied-occupied Germany (1945–1949)

- Occupation of Japan (1945–1952) after World War II

- United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands (1945–1950)

- American occupation zones in Allied-occupied Austria and Vienna (1945–1955)

- American occupation zone in West Berlin (1945–1990)

- Free Territory of Trieste (1947–1954): the U.S. co-administered a portion of the territory (between the Kingdom of Italy and the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia) with the United Kingdom.

- Operation Power Pack, Dominican Republic (1965–66)

- Grenada invasion and occupation (1983)

- Panama invasion and occupation (1989–1990)

- Operation Uphold Democracy, Haiti (1994–1995)

- Coalition Provisional Authority, Iraq (2003–2004)

- Green Zone, Iraq (March 20, 2003 – December 31, 2008)[175]

Flora and fauna

Summarize

Perspective

The territories of the United States have many plant and animal species found nowhere else in the United States. All U.S. territories have tropical climates and ecosystems.[176]

Forests

The USDA says the following about the U.S. territories (plus Hawaii):

[The U.S. territories, plus Hawaii] include virtually all the Nation's tropical forests as well as other forest types including subtropical, coastal, subalpine, dry limestone, and coastal mangrove forests. Although distant from America's geographic center and from each other—and with distinctive flora and fauna, land use history, and individual forest issues—these rich and diverse ecosystems share a common bond of change and challenge.[176]

Forests in the U.S. territories are vulnerable to invasive species and new housing developments.[176] El Yunque National Forest in Puerto Rico is the only tropical rain forest in the United States National Forest system.[177]

American Samoa has 80.84% forest cover and the Northern Mariana Islands has 80.37% forest cover—these are among the highest forest cover percentages in the United States (only Maine and New Hampshire are higher).[178][note 18]

Birds

Left: Many-colored fruit dove (found in American Samoa); Right: Golden white-eye (found only in the Northern Mariana Islands)

U.S. territories have many bird species that are endemic (not found in any other location).[176]

Introduction of the invasive brown tree snake has harmed Guam's native bird population—nine of twelve endemic species have become extinct, and the territorial bird (the Guam rail) is extinct in the wild.[176]

Puerto Rico has several endemic bird species, such as the critically endangered Puerto Rican parrot, the Puerto Rican flycatcher, and the Puerto Rican spindalis.[179] The Northern Mariana Islands has the Mariana swiftlet, Mariana crow, Tinian monarch and golden white-eye (all endemic).[180] Birds found in American Samoa include the many-colored fruit dove,[181] the blue-crowned lorikeet, and the Samoan starling.[182]

The Wake Island rail (now extinct) was endemic to Wake Island,[183] and the Laysan duck is endemic to Midway Atoll and the Northwest Hawaiian Islands.[184] Palmyra Atoll has the second-largest red-footed booby colony in the world,[185] and Midway Atoll has the largest breeding colony of Laysan albatross in the world.[186][187]

The American Birding Association currently excludes the U.S. territories from their "ABA Area" checklist.[188]

Other animals

American Samoa has several reptile species, such as the Pacific boa (on the island of Ta‘ū) and Pacific slender-toed gecko.[189] American Samoa has only a few mammal species, such as the Pacific (Polynesian) sheath-tailed bat, as well as oceanic mammals such as the Humpback whale.[190][191] Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands also have a small number of mammals, such as the Mariana fruit bat;[192] oceanic mammals include Fraser's dolphin and the Sperm whale. The fauna of Puerto Rico includes the common coquí (frog),[193] while the fauna of the U.S. Virgin Islands includes species found in Virgin Islands National Park (including 302 species of fish).[194]

American Samoa has a location called Turtle and Shark which is important in Samoan culture and mythology.[195]

Protected areas

There are two National Parks in the U.S. territories: the National Park of American Samoa, and Virgin Islands National Park.[196][197] The National Park Service also manages War in the Pacific National Historical Park on Guam.[198] There are also National Natural Landmarks, National Wildlife Refuges (such as Guam National Wildlife Refuge), El Yunque National Forest in Puerto Rico, and the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument (which includes the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands).

Public image

Summarize

Perspective

In The Not-Quite States of America, his book about the U.S. territories, essayist Doug Mack said:

It seemed that right around the turn of the twentieth century, the territories were part of the national mythology and the everyday conversation ... A century or so ago, Americans didn't just know about the territories but cared about them, argued about them. But what changed? How and why did they disappear from the national conversation?[199] The territories have made us who we are. They represent the USA's place in the world. They've been a reflection of our national mood in nearly every period of American history.[200]

Representative Stephanie Murphy of Florida said about a 2018 bill to make Puerto Rico the 51st state, "The hard truth is that Puerto Rico's lack of political power allows Washington to treat Puerto Rico like an afterthought."[201] According to Governor of Puerto Rico Ricardo Rosselló, "Because we don't have political power, because we don't have representatives, [no] senators, no vote for president, we are treated as an afterthought."[202] Rosselló called Puerto Rico the "oldest, most populous colony in the world".

Rosselló and others have referred to the U.S. territories as American "colonies".[203][204][205][206][4] David Vine of The Washington Post said the following: "The people of [the U.S. territories] are all too accustomed to being forgotten except in times of crisis. But being forgotten is not the worst of their problems. They are trapped in a state of third-class citizenship, unable to access full democratic rights because politicians have long favored the military's freedom of operation over protecting the freedoms of certain U.S. citizens."[206] In his article "How the U.S. Has Hidden Its Empire", Daniel Immerwahr of The Guardian writes, "The confusion and shoulder-shrugging indifference that mainlanders displayed [toward territories] at the time of Pearl Harbor hasn't changed much at all. [...] [Maps of the contiguous U.S.] give [mainlanders] a truncated view of their own history, one that excludes part of their country."[204] The 2020 U.S. Census excludes non-citizen U.S. nationals in American Samoa—in response to this, Mark Joseph Stern of Slate said, "The Census Bureau's total exclusion of American Samoans provides a pertinent reminder that, until the courts step in, the federal government will continue to treat these Americans with startling indifference."[207]

Galleries

Members of the House of Representatives (non-voting)

- Amata Coleman Radewagen (R), (American Samoa)

- James Moylan (R), (Guam)

- Kimberlyn King-Hinds (R), (Northern Mariana Islands)

- Pablo Hernández Rivera (D), (Puerto Rico)

- Stacey Plaskett (D), (U.S. Virgin Islands)

Territorial governors

- Pula Nikolao Pula (R), (American Samoa)

- Lou Leon Guerrero (D), (Guam)

Satellite images

- Baker Island

- Howland Island

- Jarvis Island

- Johnston Atoll

- Kingman Reef

- Midway Atoll

- Navassa Island

- Palmyra Atoll

- Wake Island

Maps

- American Samoa

- Guam

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Puerto Rico

- U.S. Virgin Islands

See also

More detail on all current territories

- Article indexes: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI

- Congressional districts: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI

- Geography: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI

- Geology: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI

- List of museums in the unincorporated territories of the United States

- List of U.S. National Historic Landmarks in the U.S. territories

- Outlines: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI

- Per capita income: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI

- Territories of the United States on stamps

- U.S. National Historic Places: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI, UM

Related topics

- Enabling act (United States)

- Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, a military base of the United States Navy in Cuba under a perpetual lease

- Historic regions of the United States

- Insular area

- List of extreme points of the United States

- List of states and territories of the United States

- Organic act

- Organized incorporated territories of the United States

- Territorial evolution of the United States

- U.S. territorial sovereignty

- U.S. Caribbean region

- 51st state

Notes

- According to the 2016 Supreme Court ruling Puerto Rico v. Sanchez Valle, territories are not sovereign.[2]

- Two additional territories (Bajo Nuevo Bank and Serranilla Bank) are claimed by the United States but administered by Colombia—if these two territories are counted, the total number of U.S. territories is sixteen.

- The U.S. General Accounting Office reports, "Some residents of the Stewart Islands in the Solomon Islands group [ Sikaiana ] ... claim that they are native Hawaiians and U.S. citizens. ... They base their claim on the assertion that the Stewart Islands were ceded to King Kamehameha IV and accepted by him as part of the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1856 and, thus, were part of the Republic of Hawaii (which was declared in 1893) when it was annexed to the United States by law in 1898." However, Sikaiana was not included within "Hawaii and its dependencies".[11]

- Two territories (Puerto Rico and the Northern Mariana Islands) are called "commonwealths".

- In Tuaua v. United States, the DC Circuit ruled that citizenship-at-birth is not a right in unincorporated regions of the U.S.—current citizenship-at-birth in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands exists only because the U.S. Congress passed legislation granting it for those territories, and Congress has not done so for American Samoa.[26] The Supreme Court declined to rule on the case.[29][30] In 2021, the 10th Circuit ruled similarly in Fitisemanu v. United States.[31]

- In parts of the United States other than American Samoa, non-citizen U.S. nationals cannot work in certain government jobs, vote or be elected for federal, state or most local government offices.[28][34] For those who apply for naturalization, there is no guarantee that they will become U.S. citizens.[28]

- SSI benefits are available only in the fifty states, the District of Columbia and the Northern Mariana Islands

- American Samoa, technically unorganized, is de facto organized.

- The administrative center of the Northern Mariana Islands is Capitol Hill, Saipan. However, because Saipan is governed as a single municipality, most publications refer to the capital as "Saipan".

- U.S. sovereignty took effect on November 3, 1986 (Eastern Time) and on November 4, 1986 (local Northern Mariana Islands Chamorro Time).[57]

- The revised constitution of American Samoa was approved on June 2, 1967, by Stewart L. Udall, then U.S. Secretary of the Interior, under authority granted on June 29, 1951. It became effective on July 1, 1967.[63]

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.