Hilya

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The term ḥilya (Arabic: حلية, plural: ḥilān, or ḥulān; Turkish: hilye, plural: hilyeler) denotes both a visual form in Ottoman art and a religious genre of Ottoman-Arabic literature each dealing with the physical description of Muhammad. Hilya means "ornament". They originate with the discipline of shama'il, the study of Muhammad's appearance and character, based on hadith accounts, most notably al-Tirmidhi's Shama'il al-Muhammadiyya "The Sublime Characteristics of Muhammad". In Ottoman-era folk Islam, there was a belief that reading and possessing Muhammad's description protects the person from trouble in this world and the next, it became customary to carry such descriptions, rendered in fine calligraphy and illuminated, as amulets.[1][2] In 17th-century Ottoman Turkey, ḥilān developed into an art form with a standard layout, often framed and used as a wall decoration. Later ḥilān were written for the four Rashid caliphs, the Companions of the Prophet, Muhammad's grandchildren Hasan and Husayn, and walis or saints.

Origins in hadith

Hilye, both as the literary genre and as the graphic art form, originates from shama'il, the study of Muhammad's appearance and character. The best source on this subject is considered to be al-Tirmidhi's Shama'il al-Muhammadiyya. The acceptance and influence of this work have led to the use of the term shama'il "appearance" to mean Muhammad's fine morals and unique physical beauty. As they contained hadiths describing Muhammad's spirit and physique, shama-il have been the source of ḥilān. The best known and accepted of these hadith are attributed to his son-in-law and cousin Ali.[3] The sources of ḥilān have been the six main hadith books along with other hadith sources, attributed to people such as Aisha, ibn Abbas, Abu Hurayra, and Hasan ibn Ali. While shama'il lists the physical and spiritual characteristics of Muhammad in detail, in ḥilān these are written about in a literary style.[4] Among other descriptive shama'il texts are the Dalāʾil al-Nubuwwah of al-Bayhaqi, Tariḥ-i Isfahān of Abu Nu'aym al-Isfahani, Al-Wafāʾ biFaḍāʾil al-Muṣṭafā of ibn al-Jawzi and Al-Shifa of Qadi Iyad.[4]

Literary genre

Summarize

Perspective

Although many ḥilān exist in Turkish literature, Persian literature does not have many examples of the shama'il and hilye genre. Abu Naeem Isfahani wrote a work titled Hilyetü'l-Evliya, but it is not about Muhammad. For this reason, the ḥilya is considered one of Turkey's national literary genres.[4] Turkish literature has also some early works that may have inspired the appearance of the ḥilya as a literary genre. The Vesiletü'n-necat of Süleyman Çelebi (1351–1422), and the Kitab-i Muhammediye of Yazıcıoğlu Mehmed, referred to Muhammad's characteristics.[5] A 255-verse long Risale-i Resul about the attributes of Muhammad, written by a writer with the penname of Şerifi, was presented to Şehzade Bayezid, one of the sons of Suleiman the Magnificent, at an unknown date that was presumably before the Şehzade died in 1562.[4] This is believed to be the earliest ḥilya in verse form in Turkish literature.[5] However, the Hilye-i Şerif by Mehmet Hakani (d. 1606–07) is considered the finest example of the genre (see section below).[6][7] The first ḥilya written in prose form was the Hilye-i Celile ve Şemail-i 'Aliye by Hoca Sadeddin Efendi.[5] Although the ḥilya tradition started with descriptions of Muhammad, later ḥilān were written about the first four Caliphs, the companions of the Prophet, Muhammad's grandchildren Hasan and Husayn, and walis "saints" such as Rumi.[5] The second most important ḥilya, after Hakani's, is considered to be Cevri İbrahim Çelebi's ḥilya, Hilye-i Çihar-Yar-ı Güzin (1630), about the physical appearance of the first four caliphs.[8] Another important ḥilya writer is Neşâtî (d. 1674), whose 184-verse long poem is about the physical characteristics of 14 prophets and Adam.[8] Other notable ḥilān are Dursunzâde Bakayi's Hilye'tûl-Enbiya ve Çeyar-ı Güzîn (hilye of the prophet and his four caliphs), Nahifi's (d. 1738) prose ḥilya Nüzhet-ûl-Ahyar fi Tercüment-iş-Şemîl-i and Arif Süleyman Bey's (1761) Nazire-î Hakânî.[9]

Ḥilān can be written as standalone prose or poems (often in the masnavi form). They can also be part of two other forms of Turkish Islamic literature, a mevlid (account of Muhammad's life) or a Mirʿajname or accounts of the Isra' and Mi'raj.[10]

Art form

Summarize

Perspective

While writers developed hilye as a literary genre, calligraphers and illuminators developed it into a decorative art form. Because of their supposed protective effect, a practice developed in Ottoman Turkey of the 17th century of carrying Muhammad's description on one's person.[11] Similarly, because of the belief that a house with a ḥilya will not see poverty, trouble, fear or the devil,[4] such texts came to be displayed prominently in a house. The term of 'ḥilya' was used for the art form for presenting these texts.[2] Thus, the ḥilya, as a vehicle for Muhammad's presence after his death, was believed to have a talismanic effect, capable of protecting a house, a child, a traveller, or a person in difficulty.[6] In addition, the purpose of the ḥilya is to help visualize Muhammad as a mediator between the sacred and human worlds, to connect with him by using the viewing of the ḥilya as an opportunity to send a traditional blessing upon him, and to establish an intimacy with him.[6][12][13] The pocket ḥilān were written on a piece of paper, small enough to fit in a breast pocket after being folded in three. The folding lines were reinforced with cloth or leather. Other pocket ḥilān were made of wood.[14] Hilyes to be displayed on a wall were prepared on paper mounted on wooden panels, although in the 19th century, thick paper sheets became another medium.[14] The top part of ḥilān that were laid on wooded panels were carved and cut out in the form of a crown. The crown part would be richly illuminated and miniatures of Medina, the tomb of Muhammad or the Kaaba would be placed there, together or separately.[15] Ottomans commissioned scribes to write ḥilān in fine calligraphy and had them decorated with illuminators. Serving as a textual textual portraits of prophets, ḥilya panels have decorated homes for centuries. These calligraphic panels were often framed and came to be used as wall decorations in houses, mosques and shrines, fulfilling an equivalent role to that played by images of Jesus in the Christian tradition.[13]: 276 [16] As symbolic art, they provided an aesthetically pleasing reminder of Muhammad's presence without involving the type of "graven image" unacceptable to most Muslims' sensitivities.[17] Although not common,[18] some ḥilān show the influence of Orthodox Christian icon-making because they are made like triptychs with foldable side panels. The first recorded instance of Hilye-i Sherif panels is generally believed to have been prepared by the notable scribe Hâfiz Osman (1642–1698).[14] He was one of earliest scribes known to make such works, although it has been suggested that another famous scribe, Ahmed Karahisarî (1468–1556), may have created one ḥilya panel about a century before.[19] Hafız Osman was known to have experimented with pocket ḥilān in his youth, one of these dates from 1668. Its text was written in very small naskh script and has dimensions of 22x14 cm. It consisted of a description of Mohammad in Arabic, and below that its Turkish translation, written in diagonal, to create a triangular block of text.[14] A characteristic feature of the texts shown at the centre of ḥilān is their praise for the beauty of Muhammad's physical appearance and character.[13]: 273–274 While containing a verbal description of what Muhammad looked like, a ḥilya leaves picturing Muhammad's appearance to the reader's imagination, in line with the mainly aniconic nature of Islamic art.[16]

Standard layout

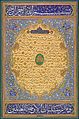

The standard layout for the Ottoman ḥilya panel is generally attributed to Hâfiz Osman. This layout is generally considered to be the best and has come to be the classical form.[9] It contains the following elements:[6]

- The baş makam "head station", a top panel containing the basmala or a blessing[2]

- The göbek ("belly"), a round shape containing the first part of the main text in naskh.[2][20] It often contains the description of Muhammad by Ali (according to Tirmidhi), with minor variations[21](see quote in the Origins section above).

- The hilâl "crescent", an optional section with no text, which is often gilded. A crescent encircling the göbek, with its thick middle part at the bottom. Together, the göbek and hilal also evoke the image of the sun and the moon.[2][20]

- The köşeler "corners", usually four rounded compartments surrounding the göbek, typically containing the names of the four Rashid caliphs according to Sunni Islam, or in some cases other titles of Muhammad, names of his companions, or some of the names of God.[2][20]

- The ayet or kuşak "belt" below the göbek and crescent containing a verse from the Quran, usually 21:107 ("And We [God] did not send you [Muhammad] except to be a mercy to the universe"), or sometimes 68:4 ("Truly, you [Muhammad] are tremendous") or 48:28–29 ("And God is significant witness that Muhammad is the messenger of God").[2][20]

- The etek "skirt" containing the conclusion of the text begun in the göbek, a short prayer, and the signature of the artist. If the main text fits completely in the göbek, the etek may be absent.[2]

- The koltuklar ("empty spaces"), two alleys or side panels on either side of the etek that typically contain ornamentation – sometimes illuminated – but no text, although occasionally the names of some of the ten companions of Muhammad are found there.[2][20]

- The iç and dış pervaz "inner and outer frame", an ornamental border in correct proportion to the text.[20]

The remainder of the space is taken up with decorative Ottoman illumination, of the type usual for the period, often with a border framing the whole in a contrasting design to the main central field that is the background of the text sections. The "verse" and "corners" normally use a larger thuluth script, while the "head" section with the bismallah is written in muhaqqaq.[22] Unlike the literary genre of ḥilya, the text on calligraphic ḥilān is generally in prose form.[11] The names in Turkish of the central structural elements of the ḥilya are, from top to bottom, başmakam (head station), göbek (belly), kuşak (belt) and etek (skirt). This anthropomorphic naming makes it clear that the ḥilya represents a human body, whose purpose is "to recall semantically the Prophet's presence via a graphic construct".[23] It has been suggested[21][23] that Hafiz Osman's ḥilya design might have been inspired by the celebrated Hilye-i Şerif, which in turn was based on the possibly spurious hadith according to which Muhammad has said "... Whoever sees my hilye after me is as though he has seen me... ". If so, a ḥilya might have been meant not to be not read but seen and contemplated because it is an image made of plain text.[21]

The standard hilye-i șerif composition has been followed by calligraphers since its creation in the late 17th century. Some examples from the 19th century and two made by Hafiz Osman can be seen below.

- Hilye by Hafiz Osman Efendi (1642–1698)

- Hilye by Hafiz Osman Efendi (1642–1698)

- Hilye by Mehmed Tahir Efendi (d. 1848)

- Hilye (1848) by Kazasker Mustafa İzzet Efendi (d. 1876).

- Hilye (c. 1853) by Niyazi Efendi (d. 1882)

However, deviations from the standard model do occur and many innovative designs have been produced as well.[2]

- Hilye (19th century). Circling around the name of Muhammad, is a five-fold repetition of the phrase, "Inna Allah ala kull shay qadir," meaning "For God hath power over all things."

- Hilye combined with blocks of text in the form of famous Relics of Muhammad. 19th century, Ottoman Turkey. Black-and-white reproduction.

- Hilye by Esmâ Ibret Hanim

- Hilye in free form (18th century).

- Hilye in the shape of a pink rose (18th century).

Popularity of the graphic form

There are several reasons given for the popularity of graphic ḥilān.[4][5] Islam prohibits the depiction of graphic representations of people that may lead to idols. For this reason, Islamic art developed in the forms of calligraphy, miniatures and other non-figurative arts. In miniatures, Muhammad's face was either veiled or blanked. Because of the prohibition on drawing the face of Muhammad, the need to represent Muhammad was satisfied by writing his name and characteristics. Many authors have commented that another reason is the affection that Muslims feel for Muhammad, which leads them to read about his physical and moral beauty.[4][5] The (apocryphal) hadith that those who memorize his ḥilya and keep it close to their heart will see Muhammad in their dreams would have been another reason. Muslim people's love for Muhammad is considered to be one of the reasons for the display of ḥilya panels at a prominent place in their homes (see Graphic art form section below). Hakani has said in his poem that a house with a ḥilya will be protected from trouble. Another motivation would have been the hadith given by Hakani in the Hilye-i Şerif, which states that those who read and memorize Muhammad's ḥilya will attain great rewards in this and the other world, will see Muhammad in their dreams, will be protected from many disasters, and will receive Muhammad's esteem. In the "sebeb-i te'lîf" ve "hâtime" section of the ḥilya, the writer gives the reasons to write the ḥilya. Hakani wrote that his reason was to be worthy of Muhammad's holy intercession (shefaat) on doomsday and to receive a prayer from willing readers. Other ḥilya writers express, usually at the end of the ḥilya, their desire to be commended to the esteem of Muhammad, the other prophets, or the four caliphs. One ḥilya writer, Hakim, wrote that he wishes that people will remember Muhammad as they look at his ḥilya.[4] Hakani's Hilye-i Şerif has been an object of affection to many Turkish people. His poem has been copied on paper as well as on wooden panels by many calligraphers and has been read with the accompaniment of music in Mawlid ceremonies.[14][24]

Non-Ottoman forms

As an art form, ḥilya has mostly been restricted to Ottoman lands. A small number of instances of ḥilya panels were made in Iran[25] and they reflect a Twelver Shi'a adaptation of the form: there is a Persian translation below the Arabic text and the names of the Twelve Imams are listed. In the 19th century, some Iranian ḥilān combined the traditional ḥilya format with the Iranian tradition of pictorial representation of Muhammad and Ali.[26][27] There are contemporary exponents of the art outside this region, such as the Pakistani calligrapher Rasheed Butt and the American calligrapher Mohamed Zakariya.[17]

Traditions

In Turkey, giving a ḥilya panel as a marriage gift for the happiness of the union and safety of the home has been a tradition that is disappearing.[14] Covering such panels with sheer curtains was part of the religious folklore in Istanbul households.[14] Since Osman's time, every Turkish calligrapher has been expected to produce at least one ḥilya, using the three muhaqqaq, thuluth and naskh scripts.[22] It is a common tradition for masters of calligraphy to obtain their diploma of competency (icazetname) after completing a ḥilya panel as their final assignment.[14] The art of ḥilya flourishes in Turkey. Contemporary artists continue to create ḥilān in the classical form as well as to innovate. Modern ḥilān maintain the essence of a ḥilya, even while the appearance of the elements of the ḥilya is customized or calligraphy is used to create abstract or figurative works.[28] Contemporary ḥilān are exhibited in major exhibitions in Turkey as well as outside the country.[29][30]

Theological opinion

According to the Süleymaniye Vakfı, a Salafi influenced religious foundation in Turkey that publishes religious opinions (fatwa), ḥilya panels are works of art, but hanging them in the home has no religious value. That is, they provide no merit to those who hang them or carry them on their persons, and those who do not possess them have no deficit.[31]

A key hilye in poetry: Hilye-i Şerif

Summarize

Perspective

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Hilye-i Şerif ("The Noble Description", 1598–1599) by Mehmet Hakani, consisting of 712 verses, lists Muhammad's features as reported by Ali (see quotation in the Origins section above), then comments on each of them in 12-20 verses.[32] Although some have found it to be of not great poetic merit, it was popular due to its subject matter.[32] The poem is significant for having established the genre of ḥilya. Later ḥilya writers such as Cevri, Nesati and Nafihi have praised Hakani and stated that they were following in his footsteps.[4] The poem contains several themes detailed below that underscore the importance of reading and writing about the attributes of Muhammad. In his ḥilya, Hakani mentions the following hadith, which he attributes to Ali:[4] A short time before Muhammad's death, when his crying daughter Fatima said to him: "Ya Rasul-Allah, I will not be able to see your face any more!" Muhammad commanded, "Ya Ali, write down my appearance, for seeing my qualities is like seeing myself." The origin of this hadith is not known. Although probably apocryphal, it has had a fundamental effect on the development of the ḥilya genre. This hadith has been repeated by most other ḥilya writers.[5] Hakani states another hadith, also attributed to Ali. This hadith of unknown origin is said to have been in circulation since the 9th century[33] but is not found in the reliable hadith collections.[12] Repeated in other ḥilān after Hakani's, this hadith has been influential in the establishment of the genre.:[4][6][17][34]

For him who sees my ḥilya after my death, it is as if he had seen me myself, and he who sees it, longing for me, for him God will make Hell prohibited, and he will not be resurrected naked on the Day of Judgement.

Hakani's ḥilya includes a story about a poor man coming to the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid and presenting him a piece of paper on which Muhammad's ḥilya is written. Al-Rashid is so delighted to see this that he regales the dervish and rewards him with sacs of jewelry. At night, he sees Muhammad in his dream. Muhammad says to him "you received and honored this poor man, so I will make you happy. God gave me the good news that whoever looks at my ḥilya and gets delight from it, presses it to his chest and protects it like his life, will be protected from hellfires on Doomsday; he will not suffer in this world nor in the other. You will be worthy of the sight of my face, and even more, of my holy lights."[4] It has become customary for other ḥilya authors that followed Hakani to mention in the introduction of their ḥilya (called havas-i hilye) the hadith that seeing Muhammad in one's dream is the same as seeing him. The Harun Al-Rashid story has also been mentioned frequently by other authors as well.[10] These elements from Hakani's ḥilya have established the belief that reading and writing ḥilān protects the person from all trouble, in this world as well as the next.

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.