Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Al-Aqsa

Islamic religious complex atop the Temple Mount in Jerusalem From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Al-Aqsa (/æl ˈæksə/; Arabic: الأَقْصَى, romanized: Al-Aqṣā) or al-Masjid al-Aqṣā (Arabic: المسجد الأقصى)[2] is the compound of Islamic religious buildings that sit atop the Temple Mount, also known as the Haram al-Sharif, in the Old City of Jerusalem, including the Dome of the Rock, many mosques and prayer halls, madrasas, zawiyas, khalwas and other domes and religious structures, as well as the four encircling minarets. It is considered the third holiest site in Islam. The compound's main congregational mosque or prayer hall is variously known as Al-Aqsa Mosque, Qibli Mosque or al-Jāmiʿ al-Aqṣā, while in some sources it is also known as al-Masjid al-Aqṣā; the wider compound is sometimes known as Al-Aqsa Mosque compound in order to avoid confusion.[3]

During the rule of the Rashidun caliph Umar (r. 634–644) or the Umayyad caliph Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680), a small prayer house on the compound was erected near the mosque's site. The present-day mosque, located on the south wall of the compound, was originally built by the fifth Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705) or his successor al-Walid I (r. 705–715) (or both) as a congregational mosque on the same axis as the Dome of the Rock, a commemorative Islamic monument. After being destroyed in an earthquake in 746, the mosque was rebuilt in 758 by the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775). It was further expanded upon in 780 by the Abbasid caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775–785), after which it consisted of fifteen aisles and a central dome. However, it was again destroyed during the 1033 Jordan Rift Valley earthquake. The mosque was rebuilt by the Fatimid caliph al-Zahir (r. 1021–1036), who reduced it to seven aisles but adorned its interior with an elaborate central archway covered in vegetal mosaics; the current structure preserves the 11th-century outline.

During the periodic renovations undertaken, the ruling Islamic dynasties constructed additions to the mosque and its precincts, such as its dome, façade, minarets, and minbar and interior structure. Upon its capture by the Crusaders in 1099, the mosque was used as a palace; it was also the headquarters of the religious order of the Knights Templar. After the area was conquered by Saladin (r. 1174–1193) in 1187, the structure's function as a mosque was restored. More renovations, repairs, and expansion projects were undertaken in later centuries by the Ayyubids, the Mamluks, the Ottomans, the Supreme Muslim Council of British Palestine, and during the Jordanian annexation of the West Bank. Since the beginning of the ongoing Israeli occupation of the West Bank, the mosque has remained under the independent administration of the Jerusalem Waqf.

Al-Aqsa holds high geopolitical significance due to its location atop the Temple Mount, in close proximity to other historical and holy sites in Judaism, Christianity and Islam, and has been a primary flashpoint in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[4]

Remove ads

Definition

Summarize

Perspective

The English term "Al-Aqsa Mosque" is the translation of both al-Masjid al-Aqṣā (ٱلْمَسْجِد ٱلْأَقْصَىٰ) and Jāmiʿ al-Aqṣā (جَامِع ٱلْأَقْصَىٰ), which have distinct Islamic meanings in Arabic.[5][6][7] The former (al-Masjid al-Aqṣā) refers to the Quran's Surah 17 – "the farthest mosque" – traditionally refers to the entirety of the Temple Mount compound, while the latter name (Jāmiʿ al-Aqṣā) is used specifically for the silver-domed congregational mosque building.[5][6][7] Arabic and Persian writers such as 10th-century geographer al-Muqaddasi,[8] 11th-century scholar Nasir Khusraw,[8] 12th-century geographer al-Idrisi[9] and 15th-century Islamic scholar Mujir al-Din,[2][10] as well as 19th-century American and British Orientalists Edward Robinson,[5] Guy Le Strange and Edward Henry Palmer explained that the term Masjid al-Aqsa refers to the entire esplanade plaza also known as the Temple Mount or Haram al-Sharif ('Noble Sanctuary') – i.e. the entire area including the Dome of the Rock, the fountains, the gates, and the four minarets – because none of these buildings existed at the time the Quran was written.[6][11][12] Al-Muqaddasi referred to the southern building (the subject of this article) as Al Mughattâ ("the covered-part") and Nasir Khusraw referred to it with the Persian word Pushish (also the "covered part," exactly as "Al Mughatta") or the Maqsurah (a part-for-the-whole synecdoche).[8]

During the period of Mamluk[13] (1250–1517) and Ottoman rule (1517–1917), the wider compound began to also be popularly known as the Haram al-Sharif, or al-Ḥaram ash-Sharīf (Arabic: اَلْـحَـرَم الـشَّـرِيْـف), which translates as the "Noble Sanctuary". It mirrors the terminology of the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca;[14][15][16][17] This term elevated the compound to the status of Haram, which had previously only been reserved for the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca and the Al-Masjid an-Nabawi in Medina. Other Islamic figures disputed the haram status of the site.[18] Usage of the name Haram al-Sharif by local Palestinians has waned in recent decades, in favor of the traditional name of Al-Aqsa Mosque.[18]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Umayyad period

In 637, the Rashidun Caliphate under Umar, the father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, besieged and captured Jerusalem from the Byzantine Empire. There are no contemporary records, but many traditions, about the origin of the main Islamic buildings on the Temple Mount.[19][20] A popular account from later centuries is that Umar was led to the place reluctantly by the Christian patriarch Sophronius.[21] He found it covered with rubbish, but the sacred Rock was found with the help of a converted Jew, Ka'b al-Ahbar.[21] Al-Ahbar advised Umar to build a mosque to the north of the rock, so that worshippers would face both the rock and Mecca, but instead Umar chose to build it to the south of the rock.[21] It became known as al-Aqsa Mosque. According to Muslim sources, Jews participated in the construction of the haram, laying the groundwork for both al-Aqsa and the Dome of the Rock mosques.[22] The first known eyewitness testimony is that of the pilgrim Arculf who visited about 670. According to Arculf's account as recorded by Adomnán, he saw a rectangular wooden house of prayer built over some ruins, large enough to hold 3,000 people.[19][23]

In 691, an octagonal Islamic building topped by a dome was built by the Caliph Abd al-Malik around the Foundation Stone, for a myriad of political, dynastic and religious reasons, built on local and Quranic traditions articulating the site's holiness, a process in which textual and architectural narratives reinforced one another.[24][25][26] The shrine became known as the Dome of the Rock (قبة الصخرة, Qubbat as-Sakhra). (The dome itself was covered in gold in 1920.) In 715 the Umayyads, led by the Caliph al-Walid I, built al-Aqsa Mosque (المسجد الأقصى, al-Masjid al-'Aqṣā, lit. "Furthest Mosque"), corresponding to the Islamic belief of Muhammad's miraculous nocturnal journey as recounted in the Quran and hadith. The term "Noble Sanctuary" or "Haram al-Sharif", as it was called later by the Mamluks and Ottomans, refers to the whole area that surrounds that Rock.[27]

A mostly wooden, rectangular prayer hall on the Temple Mount site with a capacity for 3,000 worshippers is attested by the Gallic monk Arculf during his pilgrimage to Jerusalem in c. 679–682.[28][29] Its precise location is not known.[29] The art historian Oleg Grabar deems it likely that it was close to the present prayer hall,[29] while the historian Yildirim Yavuz asserts it stood at the present site of the Dome of Rock.[30] The architectural historian K. A. C. Creswell notes that Arculf's attestation lends credibility to claims by some Islamic traditions and medieval Christian chronicles, which he otherwise deems legendary or unreliable, that the second Rashidun caliph, Umar (r. 634–644), ordered the construction of a primitive mosque on the Temple Mount. However, Arculf visited Palestine during the reign of Caliph Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680), founder of the Syria-based Umayyad Caliphate.[28] Mu'awiya had been governor of Syria, including Palestine, for about twenty years before becoming caliph and his accession ceremony was held in Jerusalem. The 10th-century Jerusalemite scholar al-Mutahhar ibn Tahir al-Maqdisi claims Mu'awiya built a mosque on the Haram.[31]

There is disagreement as to whether the present prayer hall was originally built by the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705) or his successor, his son al-Walid I (r. 705–715). Several architectural historians hold that Abd al-Malik commissioned the project and that al-Walid finished or expanded it.[a] Abd al-Malik inaugurated great architectural works on the Temple Mount, including construction of the Dome of the Rock in c. 691. A common Islamic tradition holds that Abd al-Malik simultaneously commissioned the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque.[39] As both were intentionally built on the same axis, Grabar comments that the two structures form "part of an architecturally thought-out ensemble comprising a congregational and a commemorative building", the al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, respectively.[40][b] Guy le Strange claims that Abd al-Malik used materials from the destroyed Church of Our Lady to build the mosque and points to possible evidence that substructures on the southeast corners of the mosque are remains of the church.[41]

The earliest source indicating al-Walid's work on the mosque is the Aphrodito Papryi.[42] These contain the letters between al-Walid's governor of Egypt in December 708–June 711 and a government official in Upper Egypt which discuss the dispatch of Egyptian laborers and craftsmen to help build the al-Aqsa Mosque, referred to as the "Mosque of Jerusalem".[36] The referenced workers spent between six months and a year on the construction.[43] Several 10th and 13th-century historians credit al-Walid for founding the mosque, though the historian Amikam Elad doubts their reliability on the matter.[c] In 713–714, a series of earthquakes ravaged Jerusalem, destroying the eastern section of the mosque, which was subsequently rebuilt by al-Walid's order. He had gold from the Dome of the Rock melted to use as money to finance the repairs and renovations. He is credited by the early 15th-century historian al-Qalqashandi for covering the mosque's walls with mosaics.[38] Grabar notes that the Umayyad-era mosque was adorned with mosaics, marble, and "remarkable crafted and painted woodwork".[40] The latter are preserved partly in the Palestine Archaeological Museum and partly in the Islamic Museum.[40]

Estimates of the size of the Umayyad-built mosque by architectural historians range from 112 by 39 meters (367 ft × 128 ft)[45] to 114.6 by 69.2 meters (376 ft × 227 ft).[30] The building was rectangular.[30] In the assessment of Grabar, the layout was a modified version of the traditional hypostyle mosque of the period. Its "unusual" characteristic was that its aisles laid perpendicular to the qibla wall. The number of aisles is not definitively known, though fifteen is cited by a number of historians. The central aisle, double the width of the others, was probably topped by a dome.[40]

The last years of Umayyad rule were turbulent for Jerusalem. The last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II (r. 744–750), punished Jerusalem's inhabitants for supporting a rebellion against him by rival princes, and tore down the city's walls.[46] In 746, the al-Aqsa Mosque was ruined in an earthquake. Four years later, the Umayyads were toppled and replaced by the Iraq-based Abbasid Caliphate.[47]

Abbasid period

The Abbasids generally exhibited little interest in Jerusalem,[48] though the historian Shelomo Dov Goitein notes they "paid special tribute" to the city during the early part of their rule,[46] and Grabar asserts that the early Abbasids' work on the mosque suggests "a major attempt to assert Abbasid sponsorship of holy places".[49] Nevertheless, in contrast to the Umayyad period, maintenance of the al-Aqsa Mosque during Abbasid rule often came at the initiative of the local Muslim community, rather than from the caliph.[47][40] The second Abbasid caliph, al-Mansur (r. 754–775), visited Jerusalem in 758, on his return from the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. He found the structures on the Haram in ruins from the 746 earthquake, including the al-Aqsa Mosque. According to the tradition cited by Mujir al-Din, the caliph was beseeched by the city's Muslim residents to fund the buildings' restoration. In response, he had the gold and silver plaques covering the mosque's doors converted into dinars and dirhams to finance the reconstruction.[48]

A second earthquake damaged most of al-Mansur's repairs, except for the southern portion near the mihrab (prayer niche indicating the qibla). In 780, his successor, al-Mahdi, ordered its reconstruction, mandating that his provincial governors and other commanders each contribute the cost of a colonnade.[50] Al-Mahdi's renovation is the first known to have written records describing it.[51] The Jerusalemite geographer al-Muqaddasi, writing in 985, provided the following description:

This mosque is even more beautiful than that of Damascus ... the edifice [after al-Mahdi's reconstruction] rose firmer and more substantial than ever it had been in former times. The more ancient portion remained, even like a beauty spot, in the midst of the new ... the Aqsa mosque has twenty-six doors ... The centre of the Main-building is covered by a mighty roof, high pitched and gable-wise, over which rises a magnificent dome.[52]

Al-Muqaddasi further noted that the mosque consisted of fifteen aisles aligned perpendicularly to the qibla and possessed an elaborately decorated porch with the names of the Abbasid caliphs inscribed on its gates.[49] According to Hamilton, al-Muqaddasi's description of the Abbasid-era mosque is corroborated by his archaeological findings in 1938–1942, which showed the Abbasid construction retained some parts of the older structure and had a broad central aisle topped by a dome.[53] The mosque described by al-Muqaddasi opened to the north, toward the Dome of the Rock, and, unusually according to Grabar, to the east.[49]

Other than al-Mansur and al-Mahdi, no other Abbasid caliphs visited Jerusalem or commissioned work on the al-Aqsa Mosque, though Caliph al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833) ordered significant work elsewhere on the Haram. He also contributed a bronze portal to the mosque's interior, and the geographer Nasir Khusraw noted during his 1047 visit that al-Ma'mun's name was inscribed on it.[54] Abd Allah ibn Tahir, the Abbasid governor of the eastern province of Khurasan (r. 828–844), is credited by al-Muqaddasi for building a colonnade on marble pillars in front of the fifteen doors on the mosque's front (north) side.[55]

Fatimid period

In 970, the Egypt-based Fatimid Caliphate conquered Palestine from the Ikhshidids, nominal allegiants of the Abbasids. Unlike the Abbasids and the Muslim inhabitants of Jerusalem, who were Sunnis, the Fatimids followed Shia Islam in its Isma'ili form.[56] In 1033, another earthquake severely damaged the mosque. The Fatimid caliph al-Zahir (r. 1021–1036) had the mosque reconstructed between 1034 and 1036, though work was not completed until 1065, during the reign of Caliph al-Mustansir (r. 1036–1094).[49]

The new mosque was considerably smaller, reduced from fifteen aisles to seven,[49] probably a reflection of the local population's significant decline by this time.[57][d] Excluding the two aisles on each side of the central nave, each aisle was made up of eleven arches running perpendicular to the qibla. The central nave was twice the breadth of the other aisles and had a gabled roof with a dome.[60][e] The mosque likely lacked the side doors of its predecessor.[49]

A prominent and distinctive feature of the new construction was the rich mosaic program endowed to the drum of the dome, the pendentives leading to the dome, and the arch in front of the mihrab.[60][61] These three adjoining areas covered by the mosaics are collectively referred to as the "triumphal arch" by Grabar or the "maqsura" by Pruitt.[60] Mosaic designs were rare in Islamic architecture in the post-Umayyad era and al-Zahir's mosaics were a revival of this Umayyad architectural practice, including Abd al-Malik's mosaics in the Dome of the Rock, but on a larger scale. The drum mosaic depicts a luxurious garden inspired by the Umayyad or Classical style. The four pendentives are gold and characterized by indented roundels with alternating gold and silver planes and patterns of peacock's eyes, eight-pointed stars, and palm fronds. On the arch are large depictions of vegetation emanating from small vases.[62][61]

Atop the mihrab arch is a lengthy inscription in gold directly linking the al-Aqsa Mosque with Muhammad's Night Journey (the isra and mi'raj) from the "masjid al-haram" to the "masjid al-aqsa".[63] It marked the first instance of this Quranic verse being inscribed in Jerusalem, leading Grabar to hypothesize that it was an official move by the Fatimids to magnify the site's sacred character.[57] The inscription credits al-Zahir for renovating the mosque and two otherwise unknown figures, Abu al-Wasim and a sharif, al-Hasan al-Husayni, for supervising the work.[63][f]

Nasir Khusraw described the mosque during his 1047 visit.[64] He deemed it "very large", measuring 420 by 150 cubits on its western side. The distance between each "sculptured" marble column, 280 in number, was six cubits. The columns were supported by stone arches and lead joints.[65] He noted the following features:

... the mosque is everywhere flagged with coloured marble ... The Maksurah [or space railed off for the officials] is facing the centre of the south wall [of the Mosque and Haram Area], and is of such size as to contain sixteen columns. Above rises a mighty dome that is ornamented with enamel work.[65]

Al-Zahir's substantial investment in the Haram, including the al-Aqsa Mosque, amid the political instability in the capital Cairo, rebellions by Bedouin tribes, especially the Jarrahids of Palestine, and plagues, indicate the caliph's "commitment to Jerusalem", in Pruitt's words.[66] Although the city had experienced decreases in its population in the preceding decades, the Fatimids attempted to build up the magnificence and symbolism of the mosque, and the Haram in general, for their own religious and political reasons.[g] The present-day mosque largely retains al-Zahir's plan.[69]

Fatimid investment in Jerusalem ground to a halt toward the end of the 11th century as their rule became further destabilized. In 1071, a Turkish mercenary, Atsiz, was invited by the city's Fatimid governor to rein in the Bedouin, but he turned on the Fatimids, besieging and capturing Jerusalem that year. A few years later, the inhabitants revolted against him, and were slaughtered by Atsiz, including those who had taken shelter in the al-Aqsa Mosque. He was killed by the Turkish Seljuks in 1078, establishing Seljuk rule over the city, which lasted until the Fatimids regained control in 1098.[70]

Crusader/Ayyubid/Mamluk period

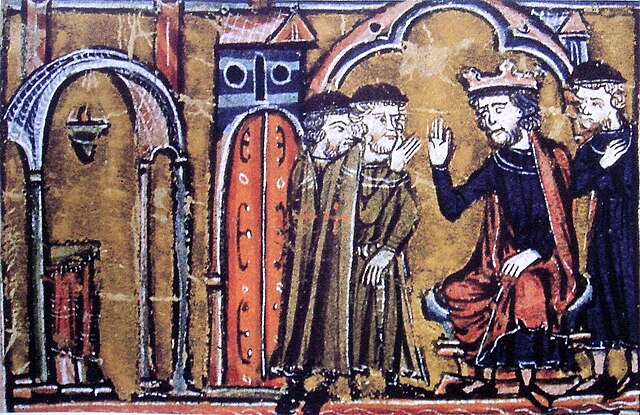

Jerusalem was captured by the Crusaders in 1099, during the First Crusade. They named the mosque Templum Solomonis (Solomon's Temple), distinguishing it from the Dome of the Rock, which they named Templum Domini (Temple of God). While the Dome of the Rock was turned into a Christian church under the care of the Augustinians,[71] the Qibli mosque was used as a royal palace and also as a stable for horses. In 1119, the Crusader king accommodated the headquarters of the Knights Templar next to his palace within the building.[72] This was probably by Baldwin II of Jerusalem and Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem at the Council of Nablus in January 1120.[73] During this period, the building underwent some structural changes, including the expansion of its northern porch, and the addition of an apse and a dividing wall. A new cloister and church were also built at the site, along with various other structures.[72] The Templars constructed vaulted western and eastern annexes to the building; the western currently serves as the women's mosque and the eastern as the Islamic Museum.[74] The Temple Mount had a mystique because it was above what were believed to be the ruins of the Temple of Solomon.[75][76]

Following the 1187 siege and recapture of Jerusalem, Saladin removed all traces of Crusader activity at the site, removing structures such as toilets and grain stores installed by the Crusaders, and oversaw various repairs and renovations at the site, returning it to its role as a mosque in time for Friday prayers within a week of his capture of the city.[77]

The ivory-set Minbar of the al-Aqsa Mosque, commissioned earlier by the Zengid sultan Nur al-Din but only completed after his death, was also added to the mosque in November 1187 by Saladin.[78] The Ayyubid sultan of Damascus, Al-Mu'azzam Isa, also built the northern porch of the mosque with three gates in 1218.[74] Further building work was carried out under the Mamluks.[79] In 1345, the Mamluks under al-Kamil Shaban added two naves and two gates to the mosque's eastern side.[74]

There are several Mamluk buildings on and around the Haram esplanade, such as the late 15th-century al-Ashrafiyya Madrasa and Sabil (fountain) of Qaytbay. The Mamluks also raised the level of Jerusalem's Central or Tyropoean Valley bordering the Temple Mount from the west by constructing huge substructures, on which they then built on a large scale. The Mamluk-period substructures and over-ground buildings are thus covering much of the Herodian western wall of the Temple Mount.

Early modern period

After the Ottomans assumed power in 1517, they did not undertake any major renovations or repairs to the mosque itself, but they did to the Noble Sanctuary as a whole. This included building the Fountain of Qasim Pasha (1527), restoring the Pool of Raranj, and building three free-standing domes—the most notable being the Dome of the Prophet built in 1538. All construction was ordered by the Ottoman governors of Jerusalem and not the sultans themselves.[80] The sultans did make additions to existing minarets, however.[80]

In 1816, the mosque was restored by Governor Sulayman Pasha al-Adil after having been in a dilapidated state.[81]

British Mandate period

Between 1922 and 1924, the Dome of the Rock and Qibli Mosque were both restored by the Supreme Muslim Council,[82] under Amin al-Husayni (the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem), who commissioned Turkish architect Ahmet Kemalettin Bey to restore al-Aqsa Mosque and the monuments in its precincts. The council also commissioned British architects, Egyptian engineering experts and local officials to contribute to and oversee the repairs and additions which were carried out in 1924–25 by Kemalettin. The renovations included reinforcing the mosque's ancient Umayyad foundations, rectifying the interior columns, replacing the beams, erecting a scaffolding, conserving the arches and drum of the main dome's interior, rebuilding the southern wall, and replacing timber in the central nave with a slab of concrete. The renovations also revealed Fatimid-era mosaics and inscriptions on the interior arches that had been covered with plasterwork. The arches were decorated with gold and green-tinted gypsum and their timber tie beams were replaced with brass. A quarter of the stained glass windows also were carefully renewed so as to preserve their original Abbasid and Fatimid designs.[83]

Severe damage was caused by the 1837 and 1927 earthquakes, but the mosque was repaired in 1938 and 1942.[74] Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini donated Carrara marble columns in the late 30s.[84]

An earthquake in 1927 and a small tremor in the summer of 1937 eventually brought down the roof of the Aqsa mosque, prompting the reconstruction of the upper part of the north wall of the mosque and the internal refacing of the whole; the partial reconstruction of the jambs and lintels of the central doors; the refacing of the front of five bays of the porch; and the demolition of the vaulted buildings that formerly adjoined the east side of the mosque.[85]

During his excavations in the 1930s, Robert Hamilton uncovered portions of a multicolor mosaic floor with geometric patterns, but did not publish them.[86] The date of the mosaic is disputed: Zachi Dvira considers that they are from the pre-Islamic Byzantine period, while Baruch, Reich and Sandhaus favor a much later Umayyad origin on account of their similarity to a mosaic from an Umayyad palace excavated adjacent to the Temple Mount's southern wall.[86] By comparing the photographs to Hamilton's excavation report, Di Cesare determined that they belong to the second phase of mosque construction in the Umayyad period.[87] Moreover, the mosaic designs were common in Islamic, Jewish and Christian buildings from the 2nd to the 8th century.[87] Di Cesare suggested that Hamilton didn't include the mosaics in his book because they were destroyed to explore beneath them.[87]

After 1948

Since 1948, the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound has been under the custodianship of the Hashemite rulers of Jordan, administered through the Jerusalem Waqf, the current version of which was instituted by Jordan after its conquest and occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, during the 1948 war.[88] The Jerusalem Waqf remained under Jordanian control after Israel occupied the Old City of Jerusalem during the Six-Day War of June 1967, though control over access to the site passed to Israel.[89]

Jordan undertook two renovations of the Dome of the Rock, replacing the leaking, wooden inner dome with an aluminum dome in 1952, and, when the new dome leaked, carrying out a second restoration between 1959 and 1964.[82]

On 21 August 1969, a fire was started by a visitor from Australia named Denis Michael Rohan,[90] an evangelical Christian who hoped that by burning down al-Aqsa Mosque he would hasten the Second Coming of Jesus.[91] In response to the incident, a summit of Islamic countries was held in Rabat that same year, hosted by Faisal of Saudi Arabia, the then king of Saudi Arabia. The al-Aqsa fire is regarded as one of the catalysts for the formation of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC, now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation) in 1972.[92]

Following the fire, the dome was reconstructed in concrete and covered with anodized aluminium, instead of the original ribbed lead enamel work sheeting. In 1983, the aluminium outer covering was replaced with lead to match the original design by az-Zahir.[93]

In the 1980s, Ben Shoshan and Yehuda Etzion, both members of the Israeli radical Gush Emunim Underground group, plotted to blow up the Al-Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock. Etzion believed that blowing up the two mosques would cause a spiritual awakening in Israel, and would solve all the problems of the Jewish people. They also hoped the Third Temple would be built on the location of the mosque.[94][95]

In 1990, the Waqf began construction of a series of outdoor minbar (pulpits) to create open-air prayer areas for use on popular holy days.[96] A monument to the victims of the Sabra and Shatila massacre was also erected.[96] In 1996, the Waqf began underground construction of the new el-Marwani Mosque in the southeastern corner of the Temple Mount. The area was claimed by the Waqf as a space that served in earlier Islamic periods as a place of prayer, but some saw the move as a part of a "political agenda"[97] and a "pretext" for the Islamization of the underground space, and believed it had been instigated to prevent the site being used a synagogue for Jewish prayers.[96][98] A spate over the use of the Golden Gate (Bab adh-Dhahabi) gatehouse as a mosque has followed in 2019.[99]

On 28 September 2000, then-opposition leader of Israel Ariel Sharon visited the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound along with 1,000 armed guards. The visit was provocative and helped spark the five-year uprising by the Palestinians commonly known as the Second Intifada, but also referred to as the al-Aqsa Intifada after the incident.[100][101][102]

On 5 November 2014, Israeli police entered the main prayer hall itself for the first time since capturing Jerusalem in 1967, according to Sheikh Azzam Al-Khatib, director of the Islamic Waqf. Previous media reports of 'storming Al-Aqsa' referred to the whole compound rather than the Qibli Mosque prayer hall itself.[103]

Remove ads

Buildings and architecture

Summarize

Perspective

The entire precinct or courtyard (sahn) of the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound can host more than 400,000 worshippers, making it one of the largest mosques in the world.[104][105] The compound comprises numerous buildings, including the Dome of the Rock, Qibli Mosque, four encircling minarets, various other domed shrines and the entry gates.

Dome of the Rock

The Dome of the Rock is the gold-domed Islamic shrine at the center of the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound. Its initial construction was undertaken by the Umayyad Caliphate on the orders of Abd al-Malik during the Second Fitna in 691–692 CE. The original dome collapsed in 1015 and was rebuilt in 1022–23. The Dome of the Rock is the world's oldest surviving work of Islamic architecture,[106][107] and its architecture and mosaics were modelled after nearby Byzantine churches and palaces,[108] although its outside appearance was significantly changed during the Ottoman period and again in the modern period, notably with the addition of the gold-plated roof, in 1959–61 and again in 1993. The octagonal plan of the structure may have been influenced by the Byzantine-era Church of the Seat of Mary (also known as Kathisma in Greek and al-Qadismu in Arabic), which was built between 451 and 458 on the road between Jerusalem and Bethlehem.[108]

The dome sits on a slightly raised platform accessed by eight staircases, each of which is topped by a free-standing arcade known in Arabic as the qanatir or mawazin. The arcades were erected in different periods from the 10th to 15th centuries.[109]

Architecture

The Dome of the Rock's structure is basically octagonal. It is capped at its centre by a dome, approximately 20 m (66 ft) in diameter, mounted on an elevated circular drum standing on 16 supports (4 tiers and 12 columns).[111] Surrounding this circle is an octagonal arcade of 24 piers and columns.[112] The octagonal arcade and the inner circular drum create an inner ambulatorium that encircles the holy rock. The outer walls are also octagonal. They each measure approximately 18 m (60 ft) wide and 11 m (36 ft) high.[111] The outer and inner octagon create a second, outer ambulatorium surrounding the inner one. Both the circular drum and the exterior walls contain many windows.[111]

The interior of the dome is lavishly decorated with mosaic, faience and marble, much of which was added several centuries after its completion. It also contains Qur'anic inscriptions. They vary from today's standard text (mainly changes from the first to the third person) and are mixed with pious inscriptions not in the Quran.[113] The decoration of the outer walls went through two major phases: the initial Umayyad scheme comprised marble and mosaics, much like the interior walls.[114] Sixteenth-century Ottoman sultan Suleyman the Magnificent replaced it with Turkish faience tiles.[114] The Ottoman tile decoration was replaced in the 1960s with faithful copies produced in Italy.[114]

Encircling archways

Surrounding the Dome of the Rock, at the top of each of the eight flights of stairs up onto the platform on which it sits, are eight freestanding sets of archways called "Al-Mawazin", each supported by 2 to 4 columns, set between two pilasters.

It is likely that some of the archways date back to the period of the construction of the Dome of the Rock and that they were an integral part of its initial construction plan. In particular, it is thought that the four arcades facing the four entrances were built at the same time as the dome.[115]

Al-Aqsa/Qibli Mosque

The Al-Aqsa Mosque or Qibli Mosque is the main congregational mosque prayer hall of the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, with capacity for around 5,000 worshippers. It has been destroyed and rebuilt several times.

During the rule of the Rashidun caliph Umar (r. 634–644) or the Umayyad caliph Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680), a small prayer house on the compound was erected near the mosque's site. The present-day mosque, located on the south wall of the compound, was originally built by the fifth Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705) or his successor al-Walid I (r. 705–715) (or both) as a congregational mosque on the same axis as the Dome of the Rock, a commemorative Islamic monument. After being destroyed in an earthquake in 746, the mosque was rebuilt in 758 by the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur. It was further expanded upon in 780 by the Abbasid caliph al-Mahdi, after which it consisted of fifteen aisles and a central dome. However, it was again destroyed during the 1033 Jordan Rift Valley earthquake. The mosque was rebuilt by the Fatimid caliph al-Zahir (r. 1021–1036), who reduced it to seven aisles but adorned its interior with an elaborate central archway covered in vegetal mosaics; the current structure preserves the 11th-century outline.

Nothing remains of the original dome built by Abd al-Malik. The present-day dome mimicks that of az-Zahir, which consisted of wood plated with lead enamelwork, but which was destroyed by fire in 1969. Today it is made of concrete with lead sheeting.[93] Al-Aqsa's dome is one of the few domes to be built in front of the mihrab during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, the others being the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus (715) and the Great Mosque of Sousse (850).[116] The interior of the dome is painted with 14th-century-era decorations. During the 1969 burning, the paintings were assumed to be irreparably lost, but were completely reconstructed using the trateggio technique, a method that uses fine vertical lines to distinguish reconstructed areas from original ones.[93]

Facade

The facade of the mosque was built in 1065 CE on the instructions of the Fatimid caliph al-Mustansir Billah. It was crowned with a balustrade consisting of arcades and small columns. The Crusaders damaged the facade, but it was restored and renovated by the Ayyubids. One addition was the covering of the facade with tiles.[74] The second-hand material of the facade's arches includes sculpted, ornamental material taken from Crusader structures in Jerusalem.[117] The facade consists of fourteen stone arches,[118][dubious – discuss] most of which are of a Romanesque style. The outer arches added by the Mamluks follow the same general design. The entrance to the mosque is through the facade's central arch.[119]

Interior

The al-Aqsa Mosque has seven aisles of hypostyle naves with several additional small halls to the west and east of the southern section of the building.[120] There are 121 stained glass windows in the mosque from the Abbasid and Fatimid eras. About a fourth of them were restored in 1924.[83] The spandrels of the arch opposite the main entrance include a mosaic decoration and inscription dating back to Fatimid period.[121]

The mosque's interior is supported by 45 columns, 33 of which are white marble and 12 of stone.[122] The column rows of the central aisles are heavy and stunted. The remaining four rows are better proportioned. The capitals of the columns are of four different kinds: those in the central aisle are heavy and primitively designed, while those under the dome are of the Corinthian order,[122] and made from Italian white marble. The capitals in the eastern aisle are of a heavy basket-shaped design and those east and west of the dome are also basket-shaped, but smaller and better proportioned. The columns and piers are connected by an architectural rave, which consists of beams of roughly squared timber enclosed in a wooden casing.[122]

A great portion of the mosque is covered with whitewash, but the drum of the dome and the walls immediately beneath it are decorated with mosaics and marble. Some paintings by an Italian artist were introduced when repairs were undertaken at the mosque after an earthquake ravaged the mosque in 1927.[122] The ceiling of the mosque was painted with funding by King Farouk of Egypt.[119]

Minbar

The minbar of the mosque was built by a craftsman named Akhtarini from Aleppo on the orders of the Zengid sultan Nur ad-Din. It was intended to be a gift for the mosque when Nur ad-Din would capture Jerusalem from the Crusaders and took six years to build (1168–74). Nur ad-Din died and the Crusaders still controlled Jerusalem, but in 1187, Saladin captured the city and the minbar was installed. The structure was made of ivory and carefully crafted wood. Arabic calligraphy, geometrical and floral designs were inscribed in the woodwork.[123]

After its destruction by Rohan in 1969, it was replaced by a much simpler minbar. In January 2007, Adnan al-Husayni—head of the Islamic waqf in charge of al-Aqsa—stated that a new minbar would be installed;[124] it was installed in February 2007.[125] The design of the new minbar was drawn by Jamil Badran based on an exact replica of the Saladin Minbar and was finished by Badran within a period of five years.[123] The minbar itself was built in Jordan over a period of four years and the craftsmen used "ancient woodworking methods, joining the pieces with pegs instead of nails, but employed computer images to design the pulpit [minbar]."[124]

Al-Marwani Mosque

The Marwani Mosque is another Islamic prayer hall situated in a large vaulted space beneath the main level of the southeastern corner of the compound, but still above the bedrock and within the enclosing walls of the Temple Mount. It is colloquially known as Solomon's Stables.[126]

The mosque consists of three hallways, the first of which acts as the main entrance, the second hallway which serves as the prayer hall with room for 4,000 worshippers, and a third which is closed off with stone.[127] The whole structure is supported by 16 stone columns and is the largest roofed space within the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound.[127] The Jerusalem Islamic Waqf acquired a permit to use Solomon's Stables in 1996 as an alternative place of worship for occasional rainy days of the holy month of Ramadan.[128]

Other domed structures

Dome of the Ascension

The Dome of the Ascension is a free-standing domed structure built by the Umayyads that stands just north the Dome of the Rock that commemorates the Islamic Prophet Muhammad's ascension (al-Miʿrāj) to heaven, according to Islamic tradition.[129]

The original edifice was probably built by either the Umayyads or the Abbasids (sometime between 7th-10th centuries),[129] while the current edifice was built by the Ayyubid governor of Jerusalem, Izz ad-Din az-Zanjili,[130] in 1200 or 1201 (during Sultan Al-Adil I's reign the brother of Saladin Al-Ayyubi[131]). An Arabic inscription dated to 1200 or 1201 (597 AH) describes it as renovated[109][132] and rededicated as a waqf.[133][134]

The dome did not exist in the Crusader era, as it was not described by Crusader travelers during their visit to the mosque during the Crusader occupation period, and there was no mention of the presence of a dome west of the Dome of the Rock.[135] The Ayyubid inscription talks about rebuilding a dome after its disappearance, guided by the information found in history books,[131] with the use of some Crusader materials.[129][136][131]

Dome of the Chain

The Dome of the Chain is a free-standing domed structure located adjacently east of the Dome of the Rock, and its exact historical use and significance are a matter of scholarly debate, but historical sources indicate it was built under the reign of Abd al-Malik, the same Umayyad caliph who built the Dome of the Rock.[137] Erected in 691–92 CE,[138] the Dome of the Chain is one of the oldest surviving structures at the al-Aqsa Mosque compound.[139]

It was built by the Umayyads, became a Christian chapel under the Crusaders, before being restored as an Islamic prayer house by the Ayyubids. It was then renovated by the Mamluks, Ottomans and the Jordanian-based waqf.

The building consists of a domed structure with two concentric open arcades, with no lateral walls closing it in. The dome, resting on a hexagonal drum, is made of timber and is supported by six columns which together create the inner arcade. The second, outer row of eleven columns creates an eleven-sided outer arcade. The qibla wall contains the mihrab or prayer niche and is flanked by two smaller columns.[138] There are a total of seventeen columns in the structure, excluding the mihrab.[140]

The columns and capitals used in the structure date to pre-Islamic times.[138] The Umayyad design of the building has largely remained unaltered by later restorations.[138]

The dome stands at the geometric centre of the esplanade which houses the al-Aqsa compound, the Haram, at the spot where the two central axes meet.[139][141] The central axes connect the centres of the opposing sides, and the Dome is also aligned on the long (approximately north-south) axis with what is presumed to be the oldest mihrab of the al-Aqsa Mosque.[141] This mihrab stands inside the 'Mosque of Omar', i.e. the southeastern section of the al-Aqsa Mosque, which corresponds by tradition to the earliest mosque built on the Temple Mount.[141] The "mihrab of Omar" as seen today stands exactly in the middle of the qibla wall of the Temple Mount.[141][142] It has been speculated that once the Dome of the Rock was built, the location of the main mihrab inside al-Aqsa Mosque has been repositioned on an axis with the centre of the Dome of the Rock, as it is until today, but the old position is preserved by the separate mihrab of the 'Mosque of Omar'.[141]

In Islamic tradition the Dome of the Chain marks the place where in the "end of days" the Last Judgment will take place, with a chain allowing passage only to the just and stopping all the sinful.[139]

Dome of al-Khalili

The Dome of al-Khalili is a small domed-building located north of the Dome of the Rock. The Dome of al-Khalili was built in the early 18th century during Ottoman rule of Palestine in dedication to Shaykh Muhammad al-Khalili, a scholar of fiqh who died in 1734.[143][144]

Dome of the Prophet

The Dome of the Prophet is a free-standing dome located on the northwest part of the elevated platform where the Dome of the Rock stands near the Dome of the Ascension.[145]

Originally, built during the Umayyad period, the dome was subsequently destroyed by the Crusaders, and rebuilt in 1539 by Muhammad Bek, Ottoman Governor of Jerusalem during the regin of Suleiman the Magnificent.[146][147] Its last renovation was in the reign of Sultan Abdul al-Majid II.[citation needed]

Several Muslim writers, most notably al-Suyuti and al-Vâsıtî claimed that the site of the dome is where Muhammad led the former prophets and angels in prayer on the night of Isra and Mir'aj before ascending to Heaven.[148][145][149][150][151] Endowment documents from the Ottoman period indicate that a portion of the endowment of the al-Aqsa Mosque and Haseki Sultan Imaret [152] was dedicated to maintain the lighting of an oil-lamp in the Dome of the Prophet each night.[153][148]

Dome of the Spirits

The Dome of the Spirits, or possibly "Dome of the Winds", is a small dome that stands to the north of the Dome of the Rock and is dated to the 16th century.[154][109] It could be associated with the proximity of the Well of Souls, where, according to legend, the souls of the dead will be gathered for prayer on the day of judgment.[citation needed]

It was probably built during Umayyad period because Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadani (3-4H/9-10th century) in his Mukhtasar Kitab al-Buldan mentioned that there was a dome in al-Aqsa enclave called Kubbat Jibril (Dome of Gabriel). Then it was called Kubbat al-Ruh and Kubbat al-Arvah (Dome of the Spirits). It was probably then rebuilt during the 10th century AH/16th century AC during the Ottoman period.[155]

Dome of Yusuf

The Dome of Yusuf is a free-standing domed structure built by Saladin (born Yusuf) in the 12th century, and has been renovated several times.[156][157][158] It bears inscriptions from the 12th and 17th centuries: one dated 1191 in Saladin's name, and two mentioning Yusuf Agha, possibly a governor of Jerusalem or a eunuch in the Ottoman imperial palace.[156][159][160]

Dome of Yusuf Agha

The Dome of Yusuf Agha is a small square building in the courtyard between the Islamic Museum and al-Aqsa Mosque (al-Qibli).

It was built in 1681 and commemorates Yusuf Agha, who also endowed the Dome of Yusuf,[161][162] a smaller and more intricate-looking structure about 120 metres (390 ft) to the north. It was converted in the 1970s into a ticket office.[161][163]

Other examples

In the southwest corner of the upper platform is a quadrangular structure which includes a portion topped by another dome. It is known as the Dome of Literature (Qubba Nahwiyya in Arabic) and dated to 1208.[109] Standing further east, close to one of the southern entrance arcades, is a stone minbar known as the "Summer Pulpit" or Minbar of Burhan al-Din, used for open-air prayers. It appears to be an older ciborium from the Crusader period, as attested by its sculptural decoration, which was then reused under the Ayyubids. Sometime after 1345, a Mamluk judge named Burhan al-Din (d. 1388) restored it and added a stone staircase, giving it its present form.[164][165]

Minarets

The mosque compound has four minarets, with three along the western perimeter of the esplanade and one along the northern wall. These are the Ghawanima Minaret, Bab al Silsila Minaret, Fakhriyya Minaret and Bab al-Asbat Minaret. The earliest dated minaret was constructed on the northwest corner of the Temple Mount in 1298, with three other minarets added over the course of the 14th century.[166][167]

Ghawanima Minaret

The Ghawanima Minaret or Al-Ghawanima Minaret was built at the northwestern corner of the Noble Sanctuary during the reign of Sultan Lajin circa 1298, or between 1297 and 1299,[166] or circa circa 1298.[167][168] It is named after Shaykh Ghanim ibn Ali ibn Husayn, who was appointed the Shaykh of the Salahiyyah Madrasah by Saladin.[169][unreliable source]

The minaret is located near the Ghawanima Gate and is the most decorated minaret of the compound.[170] It is 38.5 meters tall, with six stories and an internal staircase of 120 steps, making it the highest minaret inside the Al-Aqsa compound.[170][171] Its design may have been influenced by the Romanesque style of older Crusader buildings in the city.[168]

Bab al-Silsila Minaret (Minaret of the Chain Gate)

The Bab al-Silsila Minaret (Minaret of the Chain Gate) was built in 1329 by Tankiz, the Mamluk governor of Syria, near the Chain Gate, on the western border of the al-Aqsa Mosque.[172][173] The minaret is also known as Mahkamah Minaret since the minaret is located near the Madrasa al-Tankiziyya which served as a law court during the times of Ottomans.[174]

This minaret, possibly replacing an earlier Umayyad minaret, is built in the traditional Syrian square tower type and is made entirely out of stone.[175]

Since the 16th century, it has been a tradition that the best muezzin of the adhan (the call to prayer) is assigned to this minaret because the first call to each of the five daily prayers is raised from it, giving the signal for the muezzins of mosques throughout Jerusalem to follow suit.[176][full citation needed]

Fakhriyya Minaret

The Fakhriyya Minaret[177][178] or Al-Fakhiriyya Minaret,[179] was built on the junction of the southern wall and western wall,[180] over the solid part of the wall.[181] The exact date of its original construction is not known but it was built sometime after 1345 and before 1496.[177][182] It was named after Fakhr al-Din al-Khalili, the father of Sharif al-Din Abd al-Rahman who supervised the building's construction.[citation needed] The minaret was rebuilt in 1920.[183][verification needed][full citation needed]

The Fakhriyya Minaret was built in the traditional Syrian style, with a square-shaped base and shaft, divided by moldings into three floors above which two lines of muqarnas decorate the muezzin's balcony. The niche is surrounded by a square chamber that ends in a lead-covered stone dome.[184][full citation needed] After the minaret was damaged in the Jerusalem earthquake, the minaret's dome was covered with lead.[183]

Bab al-Asbat Minaret (Minaret of the Tribes' Gate)

The last and most notable minaret was built in 1367: the Bāb al-ʾAsbāṭ Minaret, near the Tribes' Gate (al-ʾAsbāṭ Gate). It is composed of a cylindrical stone shaft (built later by the Ottomans), which springs up from a rectangular Mamluk-built base on top of a triangular transition zone.[185] The shaft narrows above the muezzin's balcony and is dotted with circular windows, ending with a bulbous dome.[185]

The dome was reconstructed after the 1927 earthquake.[185] It was then reconstructed after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, when the minaret was bombed, causing severe damage and requiring a comprehensive restoration, as most of the minaret was damaged by the strike. The cone was also covered with lead at this time.[186]

Other features

The main compound enclosure also houses an ablution fountain (known as al-Kas), originally supplied with water via a long narrow aqueduct leading from the so-called Solomon's Pools near Bethlehem, but now supplied from Jerusalem's water mains.

Gardens take up the eastern and most of the northern side of the enclosure, with an Islamic school occupying a small part of the space.[187]

Northern and western porticos

The complex is bordered on the south and east by the outer walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. On the north and west it is bordered by two long porticos (riwaq), built during the Mamluk period.[188] A number of other structures were also built along these areas, mainly also from the Mamluk period. On the north side, they include the Isardiyya Madrasa, built sometime before 1345, and the Almalikiyya Madrasa, dated to 1340.[189] On the west side, they include the Ashrafiyya Madrasa, built by Sultan Qaytbay between 1480 and 1482,[190] and the adjacent Uthmaniyya Madrasa, dated to 1437.[191] The Sabil of Qaytbay, contemporary with the Ashrafiyya Madrasa, also stands nearby.[190]

Gates

There are currently eleven open gates offering access to the Muslim Haram al-Sharif.

- Bab al-Asbat (Gate of the Tribes); north-east corner

- Bab al-Hitta/Huttah (Gate of Remission, Pardon, or Absolution); northern wall

- Bab al-Atim/'Atm/Attim (Gate of Darkness); northern wall

- Bab al-Ghawanima (Gate of Bani Ghanim); north-west corner

- Bab al-Majlis / an-Nazir/Nadhir (Council Gate / Inspector's Gate); western wall (northern third)

- Bab al-Hadid (Iron Gate); western wall (central part)

- Bab al-Qattanin (Gate of the Cotton Merchants); western wall (central part)

- Bab al-Matarah/Mathara (Ablution Gate); western wall (central part)

- Two twin gates follow south of the Ablution Gate, the Tranquility Gate and the Gate of the Chain:

- Bab as-Salam / al-Sakina (Tranquility Gate / Gate of the Dwelling), the northern one of the two; western wall (central part)

- Bab as-Silsileh (Gate of the Chain), the southern one of the two; western wall (central part)

- Bab al-Magharbeh/Maghariba (Moroccans' Gate/Gate of the Moors; see Maghrebis); western wall (southern third); the only entrance for non-Muslims

A twelfth gate still open during Ottoman rule is now closed to the public:

- Bab as-Sarai (Gate of the Seraglio); a small gate to the former residence of the Pasha of Jerusalem; western wall, northern part (between the Bani Ghanim and Council gates).

Remove ads

Current situation

Summarize

Perspective

Administration

The administrative body responsible for the whole Al-Aqsa Mosque compound is known as "the Jerusalem Waqf", an organ of the Jordanian government.[192][193]

The Jerusalem Waqf is responsible for administrative matters in the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound. Religious authority on the site, on the other hand, is the responsibility of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, appointed by the government of the State of Palestine.[194]

After the 1969 arson attack, the waqf employed architects, technicians and craftsmen in a committee that carry out regular maintenance operations. The Islamic Movement in Israel and the waqf have attempted to increase Muslim control of the Temple Mount as a way of countering Israeli policies and the escalating presence of Israeli security forces around the site since the Second Intifada. Some activities included refurbishing abandoned structures and renovating.[195]

Ownership of the al-Aqsa Mosque is a contentious issue in the Israel-Palestinian conflict. During the negotiations at the 2000 Camp David Summit, Palestinians demanded complete ownership of the mosque and other Islamic holy sites in East Jerusalem.[196]

Access

Muslims who are residents of Israel or visiting the country and Palestinians living in East Jerusalem are normally allowed to enter the Temple Mount and pray at al-Aqsa Mosque without restrictions.[197] Due to security measures, the Israeli government occasionally prevents certain groups of Muslims from reaching al-Aqsa by blocking the entrances to the complex; the restrictions vary from time to time. At times, restrictions have prevented all men under 50 and women under 45 from entering, but married men over 45 are allowed. Sometimes the restrictions are enforced on the occasion of Friday prayers,[198][199] other times they are over an extended period of time.[198][200][201] Restrictions are most severe for Gazans, followed by restrictions on those from West Bank. The Israeli government states that the restrictions are in place for security reasons.[197]

Until 2000, non-Muslim visitors could enter the Al-Aqsa Mosque by getting a ticket from the Waqf. That procedure ended when the Second Intifada began. Over two decades later, the Waqf still hopes negotiations between Israel and Jordan may result in allowing visitors to enter once again.[202]

Conflicts

In April 2021, during both Passover and Ramadan, the site was a focus of tension between Israeli settlers and Palestinians. Jewish settlers broke an agreement between Israel and Jordan and performed prayers and read from the Torah inside the Al-Aqsa compound, an area normally off limits for prayer to non-Muslims.[203] On 14 April, Israeli police entered the Al-Aqsa compound and forcibly cut wires to speakers in minarets around the mosque, silencing the call to prayer, claiming the sound was interfering with an event by the Israeli president at the Western Wall.[204] On 16 April, seventy thousand Muslims prayed in the Al-Aqsa compound, the largest gathering since the beginning of the COVID pandemic; police barred most from entering the Al-Aqsa mosque.[205] In May 2021, hundreds of Palestinians were injured following clashes in the Al-Aqsa compound after reports of Israel's intention to proceed to evict Palestinians from land claimed by Israeli settlers.[206][207]

On 15 April 2022, Israeli forces entered the Al-Aqsa compound and used tear gas shells and sound bombs to disperse Palestinians who, they said, were throwing stones at policemen. Some Palestinians barricaded themselves inside the Al-Aqsa mosque, where they were detained by Israeli police. Over 150 people ended up injured and 400 arrested.[208][209][210]

On 5 April 2023, Israeli police raided Al-Aqsa, saying "agitators" who had thrown stones and fired fireworks at the police, had barricaded themselves and worshippers inside Al-Aqsa mosque. Following the incident, militants fired rockets from Gaza into southern Israel.[211]

On 14 April 2024, during a wave of Iranian strikes in Israel, Israel intercepted missiles and drones over Al-Aqsa. In response, Iranian supreme leader Ali Khamenei tweeted in Hebrew, 'Al-Quds will be in the hands of the Muslims,' and posted footage showing the Iranian missiles being intercepted by Israeli defenses above the Dome of the Rock.[212][213]

Remove ads

In popular culture

The term "al-Aqsa" as a symbol and brand-name has become popular and prevalent in the region.[18] For example, the Al-Aqsa Intifada (the uprising that broke out in September 2000), the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades (a coalition of Palestinian nationalist militias in the West Bank), al-Aqsa TV (the official Hamas-run television channel), al-Aqsa University (Palestinian university established in 1991 in the Gaza Strip), Jund al-Aqsa (a Salafist jihadist organization that was active during the Syrian Civil War), the Jordanian military periodical published since the early 1970s, and the associations of both the southern and northern branches of the Islamic Movement in Israel are all named Al-Aqsa after this site.[18]

The popular political slogan Al-Aqsa is in danger has been used to oppose efforts such as the Temple Mount Faithful's to take control of the compound, as well as to oppose archaeological investigations perceived as either undermining the structural foundations of the area or attempting to prove the existence of an ancient Jewish temple on the site.[214][215][216]

Remove ads

See also

- Islam in Israel

- Islam in the Palestinian territories

- Islamization of Palestine

- Islamization of Jerusalem – Religious transformation of Jerusalem to adopt Islamic influences since the 7th century

- Islamization of the Temple Mount – Islamic religious complex atop the Temple Mount in Jerusalem

- Islamization of Jerusalem – Religious transformation of Jerusalem to adopt Islamic influences since the 7th century

- Al-Juʽranah in Saudi Arabia, alternative location for Quranic "al-Aqsa mosque"

- List of the oldest mosques in the world

- Mosque of Omar (Jerusalem) – Mosque in the Christian Quarter of Jerusalem

- Palestinian nationalism – Movement for self-determination and sovereignty of Palestine

- Religious significance of the Syrian region – Region east of the Mediterranean Sea

- Status Quo (Jerusalem and Bethlehem) – Understanding among religious communities

- Temple denial – Historical assertion

Remove ads

Notes

- K. A. C. Creswell, the archaeologists Robert Hamilton and Henri Stern, and the historian F. E. Peters attribute the original Umayyad construction to al-Walid.[32][33] Other architectural historians, Julian Rabi,[34] Jere Bacharach,[35] and Yildirim Yavuz,[30] as well as the scholars H. I. Bell,[36] Rafi Grafman and Myriam Rosen-Ayalon,[37] and Amikam Elad,[38] assert or suggest that Abd al-Malik started the project and al-Walid finished or expanded it.

- This tradition is detailed in the work of the 15th-century Jerusalemite historian Mujir al-Din, the 15th-century historian al-Suyuti and the 11th-century Jerusalemite writers al-Wasiti and Ibn al-Murajja. The tradition cites an isnad (chain of transmission) traced to Thabit, a mid-8th-century attendant of the sanctuary complex, who transmits on the authority of Raja ibn Haywa, Abd al-Malik's court theologian who supervised the financing of the Dome of the Rock's construction.[39]

- The 10th-century historians Eutychius of Alexandria and al-Muhallabi attribute the mosque's construction to al-Walid, though they also erroneously credit him for the Dome of the Rock's construction. Other inaccuracies in their works make Elad question their reliability on the matter. A number of 13th-century historians, including Ibn al-Athir, support the claim, but Elad points out that they copy directly from the 10th-century historian al-Tabari, whose work only mentions al-Walid building the great mosques of Damascus and Medina, with the 13th-century historians adding the al-Aqsa Mosque to his roster of great building works. Traditions by sources based in nearby Ramla in the mid-8th century similarly credit al-Walid for the mosques in Damascus and Medina, but limit his role in Jerusalem to providing food for the city's Quran reciters.[44]

- A great famine during the reign of al-Ma'mun depleted the Muslim population, and the situation was exacerbated for all of the city's inhabitants during the city's plunder by the peasant rebels of al-Mubarqa.[58] The situation may have recovered by the late 10th century, but the unprecedented depredations throughout Palestine by the Bedouins of the Banu Tayy under the Jarrahids in the 1020s likely caused a substantial decrease in the population.[59]

- This description of al-Zahir's mosque is the general scholarly view and is based on archaeological studies carried out during restoration work in the 1920s and the diary of Nasir Khusraw's visit in 1047.[60]

- The inscription above the central mihrab reads

In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful, Glory to the One who took his servant for a journey by night from the masjid al-haram to the masjid al-aqsa whose precincts we have blessed. [... He] has renovated it, our lord Ali Abu al-Hasan the imam al-Zahir li-i'zaz Din Allah, Commander of the Faithful, son of al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, Commander of the Faithful, may the blessing of God be on him and his pure ancestors, and on his noble descendants [Shia religious formula alluding to the descendants of Muhammad through his daughter Fatima and her husband Ali, Muhammad's cousin]. By the hand of Ali ibn Abd al-Rahman, may God reward him. The [job] was supervised by Abu al-Wasim and al-Sharif al-Hasan al-Husaini.[63]

- The Fatimid efforts to strengthen the Muslim position in Jerusalem, starting from the reign of al-Zahir's predecessor, Caliph al-Hakim, was part of a proxy religious conflict between them and the Christian Byzantine Empire. From at least the 9th century, efforts had been underway to boost the city's Christian edifices, such as the Holy Sepulchre, and pilgrimage infrastructure by Christian powers and leaders, including the Carolingian Empire and the patriarch of Jerusalem, in the backdrop of renewed Byzantine offensive action against Islamic Syria. Recurrences of mob violence by the city's Muslims against Christians are reported in the 10th century, a time in which al-Muqaddasi laments that Christians and Jews in Jerusalem held the upper hand against the Muslims.[67] The Fatimid inscription also points to al-Zahir's reassertion of the orthodox Muslim narrative of the Night Journey and Muhammad's primacy in Islam against the claims by the Druze, a newly emergent outgrowth of Isma'ili Islam in Egypt and Syria, of al-Hakim's divinity and occultation.[68]

Remove ads

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads