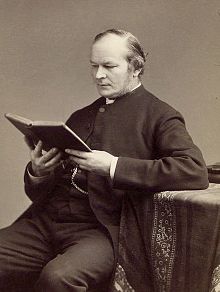

Frederic Farrar

British clergyman and author From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dean Frederic William Farrar (Bombay, 7 August 1831 – Canterbury, 22 March 1903) was a senior-ranking cleric of the Church of England, schoolteacher and author. He was a pallbearer at the funeral of Charles Darwin in 1882. He was a member of the Cambridge Apostles secret society. He was the Archdeacon of Westminster from 1883 to 1894, and Dean of Canterbury from 1895 until his death in 1903.

Dean Frederic William Farrar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 August 1831 Bombay, India |

| Died | 22 March 1903 (aged 71) Canterbury, Kent, England |

| Occupation | Cleric, writer |

| Alma mater | |

| Period | 19th century |

| Genre | Theology, children's literature |

| Subject | The Highest Heaven. Farrar commentary |

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Farrar was born in Bombay, India, and educated at King William's College on the Isle of Man, King's College London and Trinity College, Cambridge.[1] At Cambridge he won the Chancellor's Gold Medal for poetry in 1852.[2] He was for some years a master at Harrow School and, from 1871 to 1876, the headmaster of Marlborough College.

Farrar spent much of his career associated with Westminster Abbey. He was successively a canon there (appointed in 1876), rector of St Margaret's (the church next door), and eventually archdeacon of the Abbey (appointed in 1883). He later served as Dean of Canterbury;[3] and chaplain in ordinary, i.e. attached to the Royal Household.[4] He was an eloquent preacher and a voluminous author, his writings including stories of school life, such as Eric, or, Little by Little and St. Winifred's about life in a boys' boarding school in late Victorian England, and two historical romances.

Farrar was a classics scholar and a comparative philologist, who applied Charles Darwin's ideas of branching descent to the relationships between languages, engaging in a protracted debate with the anti-Darwinian linguist Max Müller.[5] While Farrar was never convinced by the evidence for evolution in biology, he had no theological objections to the idea and urged that it be considered on purely scientific grounds.[6] On Darwin's nomination, Farrar was elected to the Royal Society in 1866 for his philological work. When Darwin died in 1882, the then Canon Farrar helped get the church's permission for him to be buried in Westminster Abbey and preached the sermon at his funeral.[6]

Farrar's religious writings included Life of Christ (1874), which had great popularity, and Life of St. Paul (1879). He also contributed, first as Canon Farrar then as Archdeacon Farrar, two volumes to the commentary series The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges, on the Gospel according to St. Luke and on the Epistle to the Hebrews. His works were translated into many languages, especially Life of Christ.

Farrar believed that some could be saved after death.[7][8] He originated the term "abominable fancy" for the longstanding Christian idea that the eternal punishment of the damned would entertain the saved.[9] Farrar published Eternal Hope in 1878 and Mercy and Judgment in 1881, both of which defend his position on hell at length.[7][10]

Farrar was accused of universalism, but he denies this belief with great certainty. In 1877 Farrar in an introduction to five sermons he wrote, in the preface he attacks the idea that he holds to universalism. He also dismisses any accusation from those who would say otherwise. He says, "I dare not lay down any dogma of Universalism; partly because it is not clearly revealed to us, and partly because it is impossible for us to estimate the hardening effect of obstinate persistence in evil, and the power of the human will to resist the law and reject the love of God."[10]

In April 1882, the then Canon Farrar was one of ten pallbearers at the funeral of Charles Darwin in Westminster Abbey; the others were: The Duke of Devonshire, The Duke of Argyll, The Earl of Derby, Mr. J. Russell Lowell, Mr. W. Spottiswoode, Sir Joseph Hooker, Mr. A. R. Wallace, Thomas Huxley, and Sir John Lubbock (John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury)[11][12]

Family

Summarize

Perspective

On 1 August 1860 at St Leonard's Church, Exeter, he married Lucy Mary Cardew; they had five sons and five daughters:[11]

- Reginald Anstruther Farrar (1861–)

- Evelyn Lucy Farrar (1862–)

- Hilda Cardew Farrar (1863–1908)

- Maud Farrar (1864–1949)

- Eric Maurice Farrar (1866–)

- Sibyl Farrar (1867–)

- Cyril Lytton Farrar (1869–)

- Lilian Farrar (1870–)

- Frederic Percival Farrar (1871–1946)

- Ivor Granville Farrar (1874–1944) (born Bernard Farrar)

The first eight were born at Harrow; the last two were born at Marlborough.

The second daughter, Hilda, was married in 1881 to John Stafford Northcote, vicar of St Andrew's, Westminster. John was the third son of Sir Stafford Northcote, 1st Baronet (later created the 1st Earl of Iddesleigh); John and Hilda's son Henry (1901–1970) succeeded as the 3rd Earl of Iddesleigh in 1927.

Farrar allowed his third daughter, Maud, to become engaged to Henry Montgomery at 14 and marry at 16, the marriage taking place in 1881. The then Canon Farrar was Rector of St Margaret's, Westminster at the time, and Montgomery was the curate. Montgomery went on to become Bishop of Tasmania. Henry and Maud's children included Field Marshal The 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, better known as 'Monty', a senior-ranking military commander in World War II.[13]

Farrar's son Reginald published his biography in 1902.[6] Dean Farrar died on 22 March 1903 and was buried in the cloister of the Canterbury Cathedral.[11]

Farrar has a street named after him – Dean Farrar Street in Westminster, London. There is also a memorial to him at the church of St Margaret's, Westminster by the sculptor Nathaniel Hitch.

Works

- An Essay on the Origin of Language (1860)

- Chapters on Language (1865)

- Life of Christ (1874)

- Eternal Hope (1878)

- The Vow of the Nazarite (1879)

- Mercy and Judgement (1881)

- Life and Works of St. Paul (1879)

- History of Interpretation (1886)

- Lives of the Fathers Volume 1 (1889)

- Lives of the Fathers Volume 2 (1889)

- The Gospel According to St Luke Volume 40 in the Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges (1891)

- The Epistle of Paul to the Hebrews Volume 65 in The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges (1891)

- The Voice from Sinai (1892)

- The Bible: Its Meaning and Supremacy (1897)

- The Early Days of Christianity (1882)

Fiction

- Eric, or Little by Little, a school story (1858)

- Julian Home, a college story (1859)

- St Winifred's, or The World of School (1862)

- Darkness and Dawn, or Scenes in the Days of Nero (1891)

- Gathering Clouds: A Tale of the Days of St. Chrysostom (1895)

- Truths to Live By (1890)

Notes

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.