Filipino Americans

Americans of Filipino descent From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Filipino Americans (Filipino: Mga Pilipinong Amerikano) are Americans of Filipino ancestry. Filipinos in North America were first documented in the 16th century[9] and other small settlements beginning in the 18th century.[10] Mass migration did not begin until after the end of the Spanish–American War at the end of the 19th century, when the Philippines was ceded from Spain to the United States in the Treaty of Paris.[11][12]

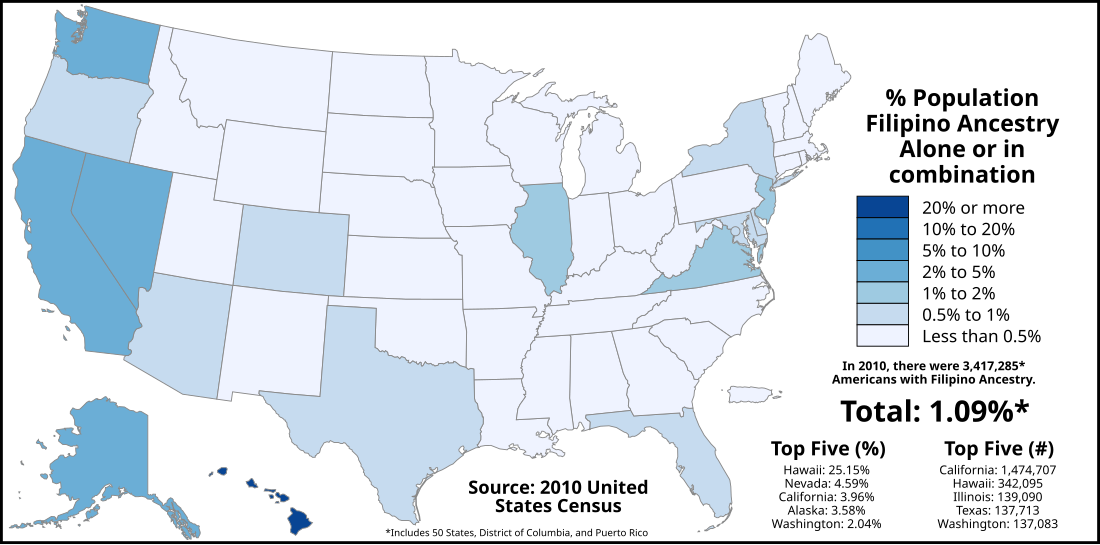

Map depicting Filipino Americans percentage-wise by U.S. state, per the 2010 US census | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 4,640,313 (2023)[1] (ancestry or ethnic origin) 2,051,900 (2023)[2] (born in the Philippines) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Western United States, Hawaii, especially in metropolitan areas and elsewhere as of 2010 | |

| California | 1,651,933[3] |

| Hawaii | 367,364[3] |

| Texas | 194,427[3] |

| Washington | 178,300[3] |

| Nevada | 169,462[3] |

| Illinois | 159,385[3] |

| New York | 144,436[3] |

| Florida | 143,481[3] |

| New Jersey | 129,514[3] |

| Virginia | 108,128[3] |

| Languages | |

| English (American, Philippine),[4] Tagalog (Filipino),[4][5] Ilocano, Pangasinan, Kapampangan, Bikol, Visayan languages (Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Waray, Chavacano), and other languages of the Philippines[4] Spanish, Chinese (Minnan and Fujien)[6][7] | |

| Religion | |

| 65% Roman Catholicism 21% Protestantism 8% Irreligion 1% Buddhism[8] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Overseas Filipinos, Hispanic and Latino Americans | |

As of 2022, there were almost 4.5 million Filipino Americans in the United States[13][14] with large communities in California, Hawaii, Illinois, Texas, Florida, Nevada, and the New York metropolitan area.[15] Around one third of Filipino Americans identify as multiracial or multiethnic, with 3 million reporting only Filipino ancestry and 1.5 million reporting Filipino in combination with another group.[16][17]

Terminology

The term Filipino American is sometimes shortened to Fil-Am[18] or Pinoy.[19] Another term which has been used is Philippine Americans.[20] The earliest appearance of the term Pinoy (feminine Pinay), was in a 1926 issue of the Filipino Student Bulletin.[21] Some Filipinos believe that the term Pinoy was coined by Filipinos who came to the United States to distinguish themselves from Filipinos living in the Philippines.[22] Beginning in 2017, started by individuals who identify with the LGBT+ Filipino-American population, there is an effort to adopt the term FilipinX; this new term has faced opposition within the broader overseas Filipino diaspora, within the Philippines, and in the United States, with some who are in opposition believing it is an attempt of a "colonial imposition".[23]

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Filipino sailors were the first Asians in North America.[24] The first documented presence of Filipinos in what is now the United States dates back to October 1587 around Morro Bay, California,[25] with the first permanent settlement in Saint Malo, Spanish Louisiana, in 1763,[26] the settlers there were called "Manilamen" and they served in the Battle of New Orleans during the closing stages of the War of 1812, after the Treaty of Ghent had already been signed.[27] There were then small settlements of Filipinos beginning in the 18th century,[28] and Filipinos worked as cowboys and ranch hands in the 1800s.[29] There was also a settlement in Plaquemines Parish, which became known as "Manila Village". This area was the center of the shrimp drying industry in Louisiana, and its workforce was composed predominantly of Filipino migrants.[30] Mass migration began in the early 20th century when, for a period following the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the Philippines was a territory of the United States. By 1904, Filipino peoples of different ethnic backgrounds were imported by the U.S. government onto the Americas and were displayed at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition as part of a human zoo.[31][32] During the 1920s, many Filipinos immigrated to the United States as unskilled labor, to provide better opportunities for their families back at home.[33]

Philippine independence was recognized by the United States on July 4, 1946. After independence in 1946, Filipino-American numbers continued to grow. Immigration was reduced significantly during the 1930s, except for those who served in the United States Navy, and increased following immigration reform in the 1960s.[34] The majority of Filipinos who immigrated after the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 were skilled professionals and technicians.[33]

The 2010 census counted 3.4 million Filipino Americans;[35] the United States Department of State in 2011 estimated the total at 4 million, or 1.1% of the U.S. population.[36] They are the country's second-largest self-reported Asian ancestry group after Chinese Americans according to 2010 American Community Survey.[37][38] They are also the largest population of Overseas Filipinos.[39] Significant populations of Filipino Americans can be found in California, Florida, Texas, Hawaii, the New York metropolitan area, and Illinois.

Culture

Summarize

Perspective

The history of Spanish and American rule and contact with merchants and traders culminated in a unique blend of Eastern and Western cultures in the Philippines.[40] Filipino-American cultural identity has been described as fluid, adopting aspects from various cultures;[41] that said, there has not been significant research into the culture of Filipino Americans.[42] Fashion, dance, music, theater and arts have all had roles in building Filipino-American cultural identities and communities.[43][page needed]

In areas of sparse Filipino population, they often form loosely-knit social organizations aimed at maintaining a "sense of family", which is a key feature of Filipino culture. These organizations generally arrange social events, especially of a charitable nature, and keep members up-to-date with local events.[44] Organizations are often organized into regional associations.[45] The associations are a small part of Filipino-American life. Filipino Americans formed close-knit neighborhoods, notably in California and Hawaii.[46] A few communities have "Little Manilas", civic and business districts tailored for the Filipino-American community.[47] In a Filipino party, shoes should be left in the front of the house and greet everyone with a hi or hello. When greeting older relatives, 'po' and 'opo' must be said in every sentence to show respect.[48]

Some Filipinos have traditional Philippine surnames, such as Bacdayan or Macapagal, while others have surnames derived from Japanese, Indian, and Chinese and reflect centuries of trade with these merchants preceding European and American rule.[49][50][51][52] Reflecting its 333 years of Spanish rule, many Filipinos adopted Hispanic surnames,[50][7] and celebrate fiestas.[53]

Despite being from Asia, Filipinos are sometimes called "Latinos" due to their historical relationship to Spanish colonialism;[54] this view is not universally accepted.[55] The Philippines experienced both Spanish and American colonial territorial status,[a] with its population seen through each nation's racial constructs.[65] This shared history may also contribute to why some Filipinos choose to also identify as Hispanic or Latino, while others may not and identify more as Asian Americans.[66] In a 2017 Pew Research Survey, only 1% of immigrants from the Philippines identified as Hispanic.[67]

Due to history, the Philippines and the United States are connected culturally.[68] In 2016, there was $16.5 billion worth of trade between the two countries, with the United States being the largest foreign investor in the Philippines, and more than 40% of remittances came from (or through) the United States.[69] In 2004, the amount of remittances coming from the United States was $5 billion;[70] this is an increase from the $1.16 billion sent in 1991 (then about 80% of total remittances being sent to the Philippines), and the $324 million sent in 1988.[71] Some Filipino Americans have chosen to retire in the Philippines, buying real estate.[72][73] Filipino Americans, continue to travel back and forth between the United States and the Philippines, making up more than a tenth of all foreign travelers to the Philippines in 2010;[73][74] when traveling back to the Philippines they often bring cargo boxes known as a balikbayan box.[75]

Language

Filipino and English are constitutionally established as official languages in the Philippines, and Filipino is designated as the national language, with English in wide use.[76] Many Filipinos speak Philippine English, a dialect derived from American English due to American colonial influence in the country's education system and due to limited Spanish education.[77] Among Asian Americans in 1990, Filipino Americans had the smallest percentage of individuals who had problems with English.[78] In 2000, among U.S.-born Filipino Americans, three quarters responded that English is their primary language;[79] nearly half of Filipino Americans speak English exclusively.[80]

In 2003, Tagalog was the fifth-most-spoken language in the United States, with 1.262 million speakers;[5] by 2011, it was the fourth most-spoken language in the United States.[81] Tagalog usage is significant in California, Nevada, and Washington, while Ilocano usage is significant in Hawaii.[82] Many of California's public announcements and documents are translated into Tagalog.[83] Tagalog is also taught in some public schools in the United States, as well as at some colleges.[84] Other significant Filipino languages are Ilocano and Cebuano.[85] Other languages spoken in Filipino-American households include Pangasinan, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Bicolano and Waray.[86] However, fluency in Philippine languages tends to be lost among second- and third-generation Filipino Americans.[87] Other languages of the community include Spanish and Chinese (Hokkien and Mandarin).[6] The demonym, Filipinx, is a gender-neutral term that is applied only to those of Filipino heritage in the diaspora, specifically Filipino Americans. The term is not applied to Filipinos in the Philippines.[88][89]

Religion

Religious Makeup of Filipino-Americans (2012)[90]

- Catholicism (65%)

- Evangelical Protestant (12%)

- Mainline Protestant (9%)

- Unaffiliated (8%)

- Other Christian (3%)

- Buddhism (1%)

- Other (2%)

The Philippines is 90% Christian,[53][91] one of only two predominantly Christian countries in Southeast Asia, alongside East Timor.[92] Following the European arrival to the Philippines by Ferdinand Magellan, Spaniards made a concerted effort to convert Filipinos to Catholicism; outside of the Muslim sultanates and animist societies, missionaries were able to convert large numbers of Filipinos.[91] and the majority are Roman Catholic, giving Catholicism a major impact on Filipino culture.[93] Other Christian denominations include Protestants (Aglipayan, Episcopalian, and others), and nontrinitarians (Iglesia ni Cristo and Jehovah's Witnesses).[93] Additionally there are those Filipinos who are Muslims, Buddhist or nonreligious; religion has served as a dividing factor within the Philippines and Filipino-American communities.[93]

During the early part of the United States governance in the Philippines, there was a concerted effort to convert Filipinos into Protestants, and the results came with varying success.[94] As Filipinos began to migrate to the United States, Filipino Roman Catholics were often not embraced by their American Catholic brethren, nor were they sympathetic to a Filipino-ized Catholicism, in the early 20th century.[95][96] This led to creation of ethnic-specific parishes;[95][97] one such parish was St. Columban's Church in Los Angeles.[98] In 1997, the Filipino oratory was dedicated at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, owing to increased diversity within the congregations of American Catholic parishes.[99] The first-ever American Church for Filipinos, San Lorenzo Ruiz Church in New York City, is named after the first saint from the Philippines, San Lorenzo Ruiz. This was officially designated as a church for Filipinos in July 2005, the first in the United States, and the second in the world, after a church in Rome.[100]

In 2010, Filipino American Catholics were the largest population of Asian American Catholics, making up more than three fourths of Asian American Catholics.[101] In 2015, a majority (65%) of Filipino Americans identify as Catholic;[102] this is down slightly from 2004 (68%).[103] Filipino Americans, who are first-generation immigrants were more likely to attend mass weekly, and tended to be more conservative, than those who were born in the United States.[104] Culturally, some traditions and beliefs rooted from the original indigenous religions of Filipinos are still known among the Filipino diaspora.[105][106]

Cuisine

The number of Filipino restaurants does not reflect the size of the population.[107][108][109] Due to the restaurant business not being a major source of income for the community, few non-Filipinos are familiar with the cuisine.[110] Although American cuisine influenced Filipino cuisine,[111] it has been criticized by non-Filipinos.[112] Even on Oahu where there is a significant Filipino-American population,[113] Filipino cuisine is not as noticeable as other Asian cuisines.[114] One study found that Filipino cuisine was not often listed in food frequency questionnaires.[115] On television, Filipino cuisine has been criticized, such as on Fear Factor,[116] and praised, such as on Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations,[117] and Bizarre Foods America.[118]

While "new" Filipino restaurants and fusion-type places have been opening up, traditionally, "native cuisine proved itself strong and resistant to 'fraternization' with foreign invaders. The original dishes have retained their ingredients, cooking methods, and spirit."

Filipino cuisine is much like its culture, a blend of many influences through the years of colonization. Popular Filipino dishes such as pancit has Hokkien roots, adobo from Spain and Mexico, and the use of bagoong and patis, fermented sauces that stem from Malay origins.[119]

Filipino-American chefs cook in many fine dining restaurants,[120] including Cristeta Comerford who is the executive chef in the White House,[108] though many do not serve Filipino cuisine in their restaurants.[120] Reasons given for the lack of Filipino cuisine in the U.S. include colonial mentality,[109] lack of a clear identity,[109] a preference for cooking at home,[108] a continuing preference of Filipino Americans for cuisines other than their own,[121] and the nebulous nature of Filipino cuisine itself due to its historical influences.[122] Filipino cuisine remains prevalent among Filipino immigrants,[123] with restaurants and grocery stores catering to the Filipino-American community,[107][124] including Jollibee, a Philippines-based fast-food chain.[125]

In the 2010s, successful and critically reviewed Filipino-American restaurants were featured in The New York Times.[126] That same decade began a Filipino Food movement in the United States;[127] it has been criticized for gentrification of the cuisine.[128] Bon Appetit named Bad Saint in Washington, D.C. "the second best new restaurant in the United States" in 2016.[129] Food & Wine named Lasa, in Los Angeles, one of its restaurants of the year in 2018.[130] With this emergence of Filipino-American restaurants, food critics like Andrew Zimmern have predicted that Filipino food will be "the next big thing" in American cuisine.[131] Yet in 2017, Vogue described the cuisine as "misunderstood and neglected";[132] SF Weekly in 2019, later described the cuisine as "marginal, underappreciated, and prone to weird booms-and-busts".[133]

Family

Filipino Americans undergo experiences that are unique to their own identities. These experiences derive from both the Filipino culture and American cultures individually and the dueling of these identities as well. These stressors, if great enough, can lead Filipino Americans into suicidal behaviors.[134] Members of the Filipino community learn early on about kapwa, which is defined as "interpersonal connectedness or togetherness".[135]

With kapwa, many Filipino Americans have a strong sense of needing to repay their family members for the opportunities that they have been able to receive. An example of this is a new college graduate feeling the need to find a job that will allow them to financially support their family and themselves. This notion comes from "utang na loob", defined as a debt that must be repaid to those who have supported the individual.[136]

With kapwa and utang na loob as strong forces enacting on the individual, there is an "all or nothing" mentality that is being played out. In order to bring success back to one's family, there is a desire to succeed for one's family through living out a family's wants as opposed to one's own true desires.[137] This can manifest as one entering a career path that they are not passionate in, but select in order to help support their family.[138]

Despite many of the stressors for these students deriving from family, it also becomes apparent that these are the reasons that these students are resilient. When family conflict rises in Filipino-American families, there is a negative association with suicide attempts.[134] This suggests that though family is a presenting stressor in a Filipino American's life, it also plays a role for their resilience.[134] In a study conducted by Yusuke Kuroki, family connectedness, whether defined as positive or negative to each individual, served as one means of lowering suicide attempts.[134]

Media

Beginning in the late 1800s, Filipino Americans began publishing books in the United States.[139] The growth of publications for the masses in the Philippines accelerated during the American period.[139] Ethnic media serving Filipino Americans dates back to the beginning of the 20th century.[140] In 1905, pensionados at University of California, Berkeley published The Filipino Students' Magazine.[141] One of the earliest Filipino-American newspapers published in the United States, was the Philippine Independent of Salinas, California, which began publishing in 1921.[141] Newspapers from the Philippines, to include The Manila Times, also served the Filipino diaspora in the United States.[140] In 1961, the Philippine News was started by Alex Esclamado, which by the 1980s had a national reach and at the time was the largest English-language Filipino newspaper.[142] While many areas with Filipino Americans have local Filipino newspapers, one of the largest concentrations of these newspapers occur in Southern California.[143] Beginning in 1992, Filipinas began publication, and was unique in that it focused on American-born Filipino Americans of the second and third generations.[140] Filipinas ended its run in 2010, however it was succeeded by Positively Filipino in 2012 which included some of the staff from Filipinas.[144] The Filipino diaspora in the United States are able to watch programming from the Philippines on television through GMA Pinoy TV and The Filipino Channel.[145][146]

Politics

Filipino Americans have traditionally been socially conservative,[147] particularly with "second wave" immigrants;[148] the first Filipino American elected to office was Peter Aduja.[149] In the 2004 U.S. Presidential Election Republican president George W. Bush won the Filipino-American vote over John Kerry by nearly a two-to-one ratio,[150] which followed strong support in the 2000 election.[151] However, during the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election, Filipino Americans voted majority Democratic, with 50% to 58% of the community voting for President Barack Obama and 42% to 46% voting for Senator John McCain.[152][153] The 2008 election marked the first time that a majority of Filipino Americans voted for a Democratic presidential candidate.[154]

According to the 2012 National Asian American Survey, conducted in September 2012,[155] 45% of Filipinos were independent or nonpartisan, 27% were Republican, and 24% were Democrats.[153] Additionally, Filipino Americans had the largest proportions of Republicans among Asian Americans polled, a position normally held by Vietnamese Americans, leading up to the 2012 election,[155] and had the lowest job approval opinion of Obama among Asian Americans.[155][156] In a survey of Asian Americans from thirty-seven cities conducted by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, it found that of the Filipino-American respondents, 65% voted for Obama.[157] According to an exit poll conducted by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, it found that 71% of responding Filipino Americans voted for Hillary Clinton during the 2016 general election.[158]

In a survey conducted by the advocacy group Asian Americans Advancing Justice in September 2020, of the 263 Filipino American respondents, 46% identified as Democrats, 28% identified as Republicans, and 16% as independent.[159] According to interviews conducted by academic Anthony Ocampo, Filipino American supporters of Donald Trump cited their support for the former President based on support for building a border wall, tax cuts to businesses, legal immigration, school choice, opposition to abortion, opposition to affirmative action, antagonism towards the People's Republic of China, and viewing Trump as a non-racist.[160] There was an age divide among Filipino Americans, with older Filipino Americans more likely to support Trump or be Republicans, and younger Filipino Americans more likely to support Biden or be Democrats.[161] In the 2020 presidential election, Philippines Ambassador Jose Manuel Romualdez alleged that 60% of Filipino Americans reportedly voted for Joe Biden.[162] Filipino Americans were among those who were at the 2021 United States Capitol attack.[163] The news site Rappler reported the next day that Filipino-American media has heavily repeated QAnon conspiracies.[164] Rappler further reported that many Filipino Americans who voted for Trump and adhere to QAnon cite similar political opinions in the Philippines regarding Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and anti-Chinese sentiment since China has been building artificial reefs in the South China Sea near the Philippines in the 2010s, and have recently seen the Republican Party as more hardline against the Chinese government's actions.[165] Filipino Americans have also been more receptive to gun rights compared to other Asian-American ethnic groups.[166] This is in part due to the lax gun laws in the Philippines.[166]

In the 2024 election, most Filipino Americans have responded to a survey indicating 59% of them found Vice President Kamala Harris more favorably, while 29% found former President Donald Trump favorable.[167]

Due to scattered living patterns, it is nearly impossible for Filipino American candidates to win an election solely based on the Filipino-American vote.[168] Filipino-American politicians have increased their visibility over the past few decades. Ben Cayetano (Democrat), former governor of Hawaii, became the first governor of Filipino descent in the United States. The number of Congressional members of Filipino descent doubled to numbers not reached since 1937, two when the Philippine Islands were represented by non-voting Resident Commissioners, due to the 2000 senatorial election. In 2009 three Congress-members claimed at least one-eighth Filipino ethnicity;[169] the largest number to date. Since the resignation of Senator John Ensign in 2011[170] (the only Filipino American to have been a member of the Senate), and Representative Steve Austria (the only Asian Pacific American Republican in the 112th Congress[171]) choosing not to seek reelection and retire,[172] Representative Robert C. Scott was the only Filipino American in the 113th Congress.[173] In the 116th United States Congress, Scott was joined by Rep. TJ Cox, bringing the number of Filipino Americans in Congress to two.[174] In the 117th United States Congress, Scott once again became the sole Filipino-American Representative after Cox was defeated in a rematch against David Valadao.[175]

Most Filipino-American registered voters identify with or lean to the Democratic Party. About two-thirds of Filipino-American voters (68%) are Democrats or lean Democratic, while 31% are Republicans or lean Republican.[176]

Socioeconomic demographics

Summarize

Perspective

Economics

Filipino Americans are largely middle class with 62% of households being middle income. However, only 21% of Filipino-American households are Upper Income compared to 27% for all Asian households. They are less likely to be Upper Income than all Asians. Filipino Americans have high labor force participation rates and 67% of Filipino Americans are employed.[178]

Filipino Americans are more likely to live in larger, overcrowded (8.7% of Filipino housing units compared to 3.5% of total population), multi-generational (34%) households compared to the general population. The average household size for Filipino Americans in 2023 was 2.99 compared to 2.49 for the general population.[179][180][181]

The impressive annual median household income and low poverty rates must be approached with caution, for median household income represents the combined earnings of several family or household members often living in crowded and less than adequate houses.[182]

While the median household income for Filipino alone was high, per capita income for Filipino Americans was $47,819 which was significantly lower than for all Asians ($55,561) and Non-Hispanic Whites ($50,675). Individual earnings for both Filipino males and females were significantly lower than all Asians, suggesting multiple earners in a household.[183][184] Filipino-American full-time, year-round workers were paid lower than the U.S. average and had a lower average hourly wage of $29.35 than the U.S. average of $29.95 and AAPI average of $30.73 [185]

Only 39% of Filipino American men (ages 25-34) had attained a Bachelor’s degree, in comparison to 87% of Asian Indian American men, 69% of Chinese American men, 63% of Japanese American men, 62% of Korean American men, and 42 percent of Vietnamese American men. The same study showed that Filipino, Korean and Cambodian men with Bachelor's degrees have lower median wages of $30 an hour compared to Chinese and Indian immigrant men who had median wages of $40 an hour[186]

Filipino American households in Los Angeles had a net worth of $243,000 with $5,000 in debts compared to a net worth of $355,000 for White households, $595,000 for Japanese households, $408,500 for Chinese households and $460,000 for Indian American households.[187]

Filipino Americans had a significantly higher rate of food insecurity (11%) than all Asians and White Americans (6%).[188]

Filipino Americans had a lower poverty rate (7%) than the total population, this correlates with the Filipino-American unemployment rate being only 3% and a high labor force participation rate of 67%.[189][190]

There is a trend of second-generation Filipino Americans moving back to the Philippines, finding the American Dream more and more unattainable. They cite lower cost of living as the main reasons they would move back to the Philippines.[191][192] There is also a trend of Filipino Americans relocating from Hawaii and California to Nevada due to rising cost of living and housing prices.[193]

Per capita income

| Ethnicity[194] | Per capita income |

|---|---|

| As of 2023 | |

| Indian | $72,389 |

| Chinese | $62,605 |

| Japanese | $61,568 |

| Korean | $58,560 |

| White (Non Hispanic) | $50,675 |

| Filipino | $47,819 |

| Vietnamese | $40,037 |

| Total US Population | $43,313 |

Average hourly wages for full-time, year-round workers in 2019[185]

| Group | Hourly wage |

|---|---|

| Indian | $ 51.19 |

| Chinese | $ 43.35 |

| Pakistani | $ 40.50 |

| Japanese | $ 39.51 |

| Korean | $ 39.47 |

| Sri Lankan | $ 36.06 |

| Malaysian | $ 35.25 |

| Indonesian | $ 32.49 |

| Fijian | $ 31.21 |

| Mongolian | $ 31.13 |

| AAPI average | $ 30.73 |

| U.S. average | $ 29.95 |

| Bangladeshi | $ 29.70 |

| Vietnamese | $ 29.38 |

| Filipino | $ 29.35 |

| Nepalese | $ 28.44 |

| Thai | $ 27.53 |

| Tongan | $ 25.99 |

| Hawaiian | $ 25.75 |

| Samoan | $ 23.72 |

| Laotian | $ 23.61 |

| Cambodian | $ 23.12 |

| Guamanian/Chamorro | $ 23.12 |

| Burmese | $ 21.63 |

| Bhutanese | $ 15.36 |

Industry and jobs

The representation of Filipino Americans employed in health care is high.[195][196][197] Other sectors of the economy where Filipino Americans have significant representation are in the public sector,[198] and in the service sector.[199][200] Compared to Asian-American women of other ethnicities, and women in the United States in general, Filipina Americans are more likely to be part of the work force;[201] a large population, nearly one fifth (18%), of Filipina Americans worked as registered nurses.[202] There is also a large number of Filipino domestic workers and care-givers in the U.S.[203][204] More than 60% of Filipino Americans work in more than 60% work in low-wage and/or service-sector work.

Filipino Americans own a variety of businesses, making up 10.5% of all Asian owned businesses in the United States in 2007.[205] In 2002, according to the Survey of Business Owners, there were over 125,000 Filipino-owned businesses; this increased by 30.4% to over 163,000 in 2007.[206] By then, 25.4% of these businesses were in the retail industry, 23% were in the health care and social assistance industries,[207] and they employed more than 142,000 people and generated almost $15.8 billion in revenue.[205] Of those, just under three thousand (1.8% of all Filipino-owned businesses) were million dollar or more businesses. This means Filipino-owned businesses are significantly less likely to be million dollar or more than all Asians (5%).[208][209] California had the largest number of Filipino-owned businesses, with the Los Angeles metropolitan area having the largest number of any metropolitan area in the United States.[205]

The Philippines is the largest exporters of Nurses and this is something that can be traced back to U.S. colonialism.[210] America has been relying on Filipino nurses on the frontlines since the AIDs pandemic. Despite making up only 4% of Registered Nurses in the U.S., the make up nearly a third of Covid-related deaths among registered nurses.[211][212]

American schools have also hired and sponsored the immigration of Filipino teachers and instructors.[213] Some of these teachers were forced into labor outside the field of education, and mistreated by their recruiters.[214]

Among Overseas Filipinos, Filipino Americans are the largest remitters of U.S. dollars to the Philippines. In 2005, their combined dollar remittances reached a record-high of almost $6.5 billion. In 2006, Filipino Americans sent more than $8 billion, which represents 57% of the total foreign remittances received by the Philippines.[215] By 2012, this amount had reached $10.6 billion, but made up only 43% of total remittances.[216] In 2021, the United States was the largest source of remittances to the Philippines, making up 40.5% of the $31.4 billion remittances received by the Philippines.[217]

Community issues

Summarize

Perspective

Immigration

The Citizenship Retention and Re-Acquisition Act of 2003 (Republic Act No. 9225) made Filipino Americans eligible for dual citizenship in the United States and the Philippines.[218] Overseas suffrage was first employed in the May 2004 elections in which Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo was reelected to a second term.[219]

By 2005, about 6,000 Filipino Americans had become dual citizens of the two countries.[220] One effect of this act was to allow Filipino Americans to invest in the Philippines through land purchases, which are limited to Filipino citizens, and, with some limitations, former citizens.[221]), vote in Philippine elections, retire in the Philippines, and participate in representing the Philippine flag. In 2013, for the Philippine general election there were 125,604 registered Filipino voters in the United States and Caribbean, of which only 13,976 voted.[222]

Dual citizens have been recruited to participate in international sports events including athletes representing the Philippines who competed in the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens,[223] and the Olympic Games in Beijing 2008.[224]

The Philippine government actively encourages Filipino Americans to visit or return permanently to the Philippines via the "Balikbayan" program and to invest in the country.[225]

Filipinos remain one of the largest immigrant groups to date with over 40,000 arriving annually since 1979.[226] The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) has a preference system for issuing visas to non-citizen family members of U.S. citizens, with preference based generally on familial closeness. Some non-citizen relatives of U.S. citizens spend long periods on waiting lists.[227] Petitions for immigrant visas, particularly for siblings of previously naturalized Filipinos that date back to 1984, were not granted until 2006.[228] As of 2016[update], over 380 thousand Filipinos were on the visa wait list, second only to Mexico and ahead of India, Vietnam and China.[229] Filipinos have the longest waiting times for family reunification visas, as Filipinos disproportionately apply for family visas; this has led to visa petitions filed in July 1989 still waiting to be processed in March 2013.[230]

Illegal immigration

It has been documented that Filipinos were among those naturalized due to the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986.[231] In 2009, the Department of Homeland Security estimated that 270,000 Filipino were "unauthorized immigrants". This was an increase of 70,000 from a previous estimate in 2000. In both years, Filipinos accounted for 2% of the total. As of 2009[update], Filipinos were the fifth-largest community of illegal immigrants behind Mexico (6.65 million, 62%), El Salvador (530,000, 5%), Guatemala (480,000, 4%), and Honduras (320,000, 3%).[232] In January 2011, the Department of Homeland Security estimate of "unauthorized immigrants" from the Philippines remained at 270,000.[233] By 2017, the number of Filipinos who were in the United States illegally increased to 310,000.[234] Filipinos who reside in the United States illegally are known within the Filipino community as "TnT's" (tago nang tago 'hide and hide').[235]

Health

Filipino Americans experience significant health disparities and are more likely to have diabetes, heart disease, high blood preasure and other issues.[236] Filipino Americans also experience food insecurity at a significantly higher rate then other Asian-American groups.[188] In Hawaii the rate of low food security and very low food security for Filipino people were 11.7% and 22.3%.[237][238][239]

Identity

Filipino Americans may be mistaken for members of other racial/ethnic groups, such as Latinos or Pacific Islanders;[240] this may lead to "mistaken" discrimination that is not specific to Asian Americans.[240] Filipino Americans, additionally, have had difficulty being categorized, termed by one source as being in "perpetual absence".[241]

In the period, prior to 1946, Filipinos were taught that they were American, and presented with an idealized America.[226] They had official status as United States nationals.[242] When ill-treated and discriminated by other Americans, Filipinos were faced with the racism of that period, which undermined these ideals.[243] Carlos Bulosan later wrote about this experience in America is in the Heart. Even pensionados, who immigrated on government scholarships,[226] were treated poorly.[243]

In Hawaii, Filipino Americans often have little identification with their heritage,[244] and it has been documented that many disclaim their ethnicity.[245] This may be due to the "colonial mentality", or the idea that Western ideals and physical characteristics are superior to their own.[246] Although categorized as Asian Americans, Filipino Americans have not fully embraced being part of this racial category due to marginalization by other Asian-American groups and or the dominant American society.[247] This created a struggle within Filipino American communities over how far to assimilate.[248] The term "white-washed" has been applied to those seeking to further assimilate.[249] Those who disclaim their ethnicity lose the positive adjustment to outcomes that are found in those who have a strong, positive, ethnic identity.[246]

Of the ten largest immigrant groups, Filipino Americans have the highest rate of assimilation,[250] with the exception of cuisine.[251] Filipino Americans have been described as the most "Americanized" of the Asian-American ethnicities.[252] However, even though Filipino Americans are the second-largest group among Asian Americans, community activists have described the ethnicity as "invisible", claiming that the group is virtually unknown to the American public,[253] and is often not seen as significant even among its members.[254] Another term for this status is forgotten minority.[255]

This description has also been used in the political arena, given the lack of political mobilization.[256] In the mid-1990s it was estimated that some one hundred Filipino Americans have been elected or appointed to public office. This lack of political representation contributes to the perception that Filipino Americans are invisible.[257]

The concept is also used to describe how the ethnicity has assimilated.[258] Few affirmative action programs target the group although affirmative action programs rarely target Asian Americans in general.[259] Assimilation was easier given that the group is majority religiously Christian, fluent in English, and have high levels of education.[260] The concept was in greater use in the past, before the post-1965 wave of arrivals.[261]

The term invisible minority has been used for Asian Americans as a whole,[262][263] and the term "model minority" has been applied to Filipinos as well as other Asian-American groups.[264] Filipino critics allege that Filipino Americans are ignored in immigration literature and studies.[265]

As with fellow Asian Americans, Filipino Americans are viewed as "perpetual foreigners", even for those born in the United States.[266] This has resulted in physical attacks on Filipino Americans, as well as non-violent forms of discrimination.[267]

In college and high school campuses, many Filipino-American student organizations put on annual Pilipino Culture Nights to showcase dances, perform skits, and comment on issues such as identity and lack of cultural awareness due to assimilation and colonization.[268]

Filipino-American gay, lesbian, transgender, and bisexual identities are often shaped by immigration status, generation, religion, and racial formation.[269]

Suicide ideation and depression

Mental health is a topic that is seldom spoken about among the Filipino-American community because of the stigma that is attached to it.[270] In the documentary "Silent Sacrifices: Voices of the Filipino American Family" Patricia Heras points out that a lack of communication between first-generation and second-generation Filipino-American immigrants can lead to family members not understanding the personal hardships that each one goes through.[271] Some of the main topics of discussion in this documentary are depression and suicide ideation experienced by the second-generation youth.[271] These topics are supported by a study that was conducted in 1997 by the Federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that revealed that 45.6% of Filipina American teenage students in San Diego public schools had seriously thought about committing suicide. Half of those students had actually attempted suicide.[272] Although depression cannot be said to cause suicide, the high scores of depression and low self-esteem show a relation to the high scores of suicidal thoughts among Filipinos.[273]

Depression in Filipinos can sometimes be difficult to notice without digging deeper into their feelings. Filipinos can display their depression in many ways such as showing extreme suffering or smiling even when it may not seem authentic.[270] Some of the common causes of depression include: financial worries, family separation during the immigration process, and cultural conflict.[270] One of these cultural conflicts is the belief that one must base decisions on what will "save face" for the family.[274] A study was published in 2018 by Janet Chang and Frank Samson about Filipino American youth and their non-Filipino friends. They had found that Filipino American youth with three or more close non-Filipino friends were more likely to experience depression and anxiety more so than Filipino American youth with two or less non-Filipino friends that they considered to be close.[275] Although having friends of diverse backgrounds gave these Filipinos a sense of inclusion among their peers, they also gained a heightened awareness of discrimination.[275]

Veterans

During World War II, some 250,000 to 400,000 Filipinos served in the United States Military,[276][277] in units including the Philippine Scouts, Philippine Commonwealth Army under U.S. Command, and recognized guerrillas during the Japanese Occupation. In January 2013, ten thousand surviving Filipino-American veterans of World War II lived in the United States, and a further fourteen thousand in the Philippines,[278] although some estimates found eighteen thousand or fewer surviving veterans.[279]

The U.S. government promised these soldiers all of the benefits afforded to other veterans.[280] However, in 1946, the United States Congress passed the Rescission Act of 1946 which stripped Filipino veterans of the promised benefits.[281] One estimate claims that monies due to these veterans for back pay and other benefits exceeds one billion dollars.[277] Of the sixty-six countries allied with the United States during the war, the Philippines is the only country that did not receive military benefits from the United States.[254] The phrase "Second Class Veterans" has been used to describe their status.[254][282]

Many Filipino veterans traveled to the United States to lobby Congress for these benefits.[283] Since 1993, numerous bills have been introduced in Congress to pay the benefits, but all died in committee.[284] As recently as 2018, these bills have received bipartisan support.[285]

Representative Hanabusa submitted legislation to award Filipino Veterans with a Congressional Gold Medal.[286] Known as the Filipino Veterans of World War II Congressional Gold Medal Act, it was referred to the Committee on Financial Services and the Committee on House Administration.[287] As of February 2012 had attracted 41 cosponsors.[288] In January 2017, the medal was approved.[289]

There was a proposed lawsuit to be filed in 2011 by The Justice for Filipino American Veterans against the Department of Veterans Affairs.[290]

In the late 1980s, efforts towards reinstating benefits first succeeded with the incorporation of Filipino veteran naturalization in the Immigration Act of 1990.[254] Over 30,000 such veterans had immigrated, with mostly American citizens, receiving benefits relating to their service.[291]

Similar language to those bills was inserted by the Senate into the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009[292] which provided a one time payment of at least 9,000 USD to eligible non-US Citizens and US$15,000 to eligible US Citizens via the Filipino Veterans Equity Compensation Fund.[293] These payments went to those recognized as soldiers or guerrillas or their spouses.[294] The list of eligibles is smaller than the list recognized by the Philippines.[295] Additionally, recipients had to waive all rights to possible future benefits.[296] As of March 2011, 42 percent (24,385) of claims had been rejected;[297] By 2017, more than 22,000 people received about $226 million in one time payments.[298]

In the 113th Congress, Representative Joe Heck reintroduced his legislation to allow documents from the Philippine government and the U.S. Army to be accepted as proof of eligibility.[299] Known as H.R. 481, it was referred to the Committee on Veterans' Affairs.[300] In 2013, the U.S. released a previously classified report detailing guerrilla activities, including guerrilla units not on the "Missouri list".[301]

In September 2012, the Social Security Administration announced that non-resident Filipino World War II veterans were eligible for certain social security benefits; however an eligible veteran would lose those benefits if they visited for more than one month in a year, or immigrated.[302]

Beginning in 2008, a bipartisan effort started by Mike Thompson and Tom Udall an effort began to recognize the contributions of Filipinos during World War 2; by the time Barack Obama signed the effort into law in 2016, a mere fifteen thousand of those veterans were estimated to be alive.[303] Of those living Filipino veterans of World War II, there were an estimated 6,000 living in the United States.[304] Finally in October 2017, the recognition occurred with the awarding of a Congressional Gold Medal.[305] When the medal was presented by the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, several surviving veterans were at the ceremony.[306] The medal now resides in the National Museum of American History.[307]

Holidays

Summarize

Perspective

Congress established Asian Pacific American Heritage Month in May to commemorate Filipino American and other Asian American cultures. Upon becoming the largest Asian American group in California, October was established as Filipino American History Month to acknowledge the first landing of Filipinos on October 18, 1587 in Morro Bay, California. It is widely celebrated by Filipino Americans.[308][309]

| Date | Name | Region |

|---|---|---|

| January | Winter Sinulog[310] | Philadelphia |

| April | PhilFest[311] | Tampa, FL |

| May | Asian Pacific American Heritage Month | Nationwide, USA |

| May | Asian Heritage Festival[312] | New Orleans |

| May | Filipino Fiesta and Parade[313] | Honolulu |

| May | FAAPI Mother's Day[314] | Philadelphia |

| May | Flores de Mayo[315] | Nationwide, USA |

| June | Philippine Independence Day Parade | New York City |

| June | Philippine Festival[316] | Washington, D.C. |

| June | Philippine Day Parade[317] | Passaic, NJ |

| June | Pista Sa Nayon[318] | Vallejo, CA |

| June | New York Filipino Film Festival at The ImaginAsian Theatre | New York City |

| June | Empire State Building commemorates Philippine Independence[319] | New York City |

| June | Philippine–American Friendship Day Parade[320] | Jersey City, NJ |

| June 12 | Fiesta Filipina[321] | San Francisco |

| June 12 | Philippine Independence Day | Nationwide, USA |

| June 19 | Jose Rizal's Birthday[322] | Nationwide, USA |

| June | Pagdiriwang[323] | Seattle |

| July | Fil-Am Friendship Day[324] | Virginia Beach, VA |

| July | Pista sa Nayon[325] | Seattle |

| July | Filipino American Friendship Festival[326] | San Diego |

| July | Philippine Weekend[327] | Delano, CA |

| August 15 to 16 | Philippine American Exposition[328] | Los Angeles |

| August 15 to 16 | Annual Philippine Fiesta[329] | Secaucus, NJ |

| August | Summer Sinulog[330] | Philadelphia |

| August | Historic Filipinotown Festival[331] | Los Angeles |

| August | Pistahan Festival and Parade[332] | San Francisco |

| September 25 | Filipino Pride Day[333] | Jacksonville, FL |

| September | Festival of Philippine Arts and Culture (FPAC)[334] | Los Angeles |

| September | AdoboFest[335] | Chicago |

| October | Filipino American History Month | Nationwide, USA |

| October | Filipino American Arts and Culture Festival (FilAmFest)[336] | San Diego |

| October | Houston Filipino Street Festival[337] | Sugar Land, TX |

| November | Chicago Filipino American Film Festival (CFAFF)[338] | Chicago |

| December 16 to 24 | Simbang Gabi Christmas Dawn Masses[339] | Nationwide, USA |

| December 25 | Pasko Christmas Feast[340] | Nationwide, USA |

| December 30 | Jose Rizal Day | Nationwide, USA |

Notable people

Footnotes

- Other nations and territories that were once part of the Spanish Empire, that were or are part of the United States, include the Florida,[56][57] Texas,[57][58] Mexican Cession,[56][59] Gadsden Purchase,[59][60] Puerto Rico,[57][61] Guam,[62] Panama Canal Zone,[63] and Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.[64]

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.