Near and far field

Regions of an electromagnetic field From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

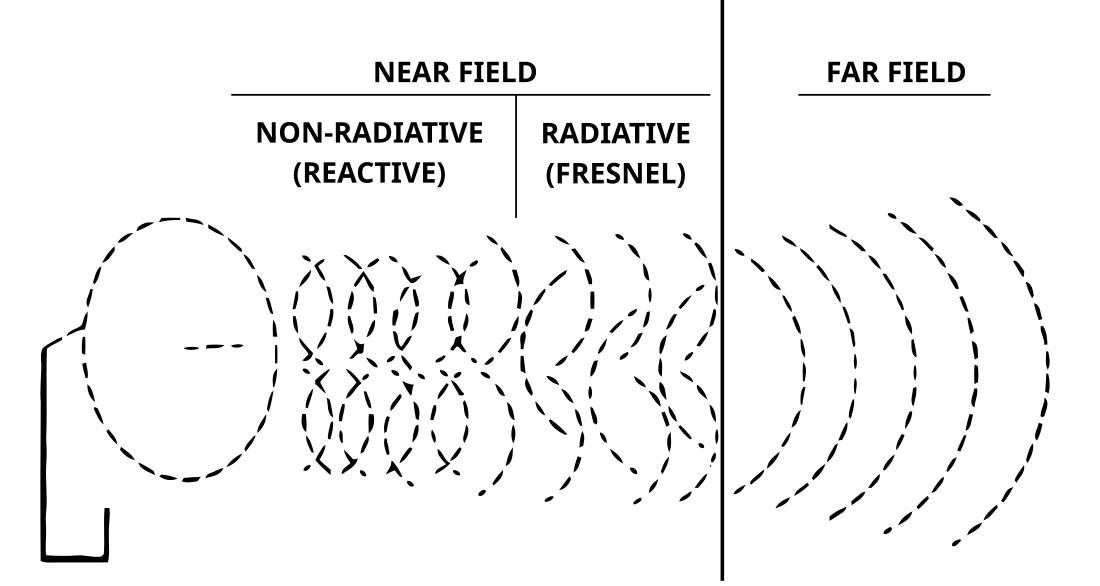

The near field and far field are regions of the electromagnetic (EM) field around an object, such as a transmitting antenna, or the result of radiation scattering off an object. Non-radiative near-field behaviors dominate close to the antenna or scatterer, while electromagnetic radiation far-field behaviors predominate at greater distances.

Far-field E (electric) and B (magnetic) radiation field strengths decrease as the distance from the source increases, resulting in an inverse-square law for the power intensity of electromagnetic radiation in the transmitted signal. By contrast, the near-field's E and B strengths decrease more rapidly with distance: The radiative field decreases by the inverse-distance squared, the reactive field by an inverse-cube law, resulting in a diminished power in the parts of the electric field by an inverse fourth-power and sixth-power, respectively. The rapid drop in power contained in the near-field ensures that effects due to the near-field essentially vanish a few wavelengths away from the radiating part of the antenna, and conversely ensure that at distances a small fraction of a wavelength from the antenna, the near-field effects overwhelm the radiating far-field.

Summary of regions and their interactions

Summarize

Perspective

In a normally-operating antenna, positive and negative charges have no way of leaving the metal surface, and are separated from each other by the excitation "signal" voltage (a transmitter or other EM exciting potential). This generates an oscillating (or reversing) electrical dipole, which affects both the near field and the far field.

The boundary between the near field and far field regions is only vaguely defined, and it depends on the dominant wavelength (λ) emitted by the source and the size of the radiating element.

Near field

The near field refers to places nearby the antenna conductors, or inside any polarizable media surrounding it, where the generation and emission of electromagnetic waves can be interfered with while the field lines remain electrically attached to the antenna, hence absorption of radiation in the near field by adjacent conducting objects detectably affects the loading on the signal generator (the transmitter). The electric and magnetic fields can exist independently of each other in the near field, and one type of field can be disproportionately larger than the other, in different subregions.

- An easy-to-observe example of a near-field effect is the change of noise levels picked up by a set of rabbit ear TV antennas when a human body part is moved in close to the "ears". Likewise the change in sound quality of an FM radio tuned to a distant station when a person walks about in the area within an arm's length of its antenna.

The near field is governed by multipole type fields, which can be considered as collections of dipoles with a fixed phase relationship. The general purpose of conventional antennas is to communicate wirelessly over long distances, well into their far fields, and for calculations of radiation and reception for many simple antennas, most of the complicated effects in the near field can be conveniently ignored.

Reactive near field

The interaction with the medium (e.g. body capacitance) can cause energy to deflect back to the source feeding the antenna, as occurs in the reactive near field. This zone is roughly within 1/6 of a wavelength of the nearest antenna surface.

The near field has been of increasing interest, particularly in the development of capacitive sensing technologies such as those used in the touchscreens of smart phones and tablet computers. Although the far field is the usual region of antenna function, certain devices that are called antennas but are specialized for near-field communication do exist. Magnetic induction as seen in a transformer can be seen as a very simple example of this type of near-field electromagnetic interaction. For example send / receive coils for RFID, and emission coils for wireless charging and inductive heating; however their technical classification as "antennas" is contentious.

Radiative near field

The interaction with the medium can fail to return energy back to the source, but cause a distortion in the electromagnetic wave that deviates significantly from that found in free space, and this indicates the radiative near-field region, which is somewhat further away. Passive reflecting elements can be placed in this zone for the purpose of beam forming, such as the case with the Yagi–Uda antenna. Alternatively, multiple active elements can also be combined to form an antenna array, with lobe shape becoming a factor of element distances and excitation phasing.

Transition zone

Another intermediate region, called the transition zone, is defined on a somewhat different basis, namely antenna geometry and excitation wavelength. It is approximately one wavelength from the antenna, and is where the electric and magnetic parts of the radiated waves first balance out: The electric field of a linear antenna gains its corresponding magnetic field, and the magnetic field of a loop antenna gains its electric field. It can either be considered the furthest part of the near field, or the nearest part of the far field. It is from beyond this point that the electromagnetic wave becomes self-propagating. The electric and magnetic field portions of the wave are proportional to each other at a ratio defined by the characteristic impedance of the medium through which the wave is propagating.

Far field

In contrast, the far field is the region in which the field has settled into "normal" electromagnetic radiation. In this region, it is dominated by transverse electric or magnetic fields with electric dipole characteristics. In the far-field region of an antenna, radiated power decreases as the square of distance, and absorption of the radiation does not feed back to the transmitter.

In the far-field region, each of the electric and magnetic parts of the EM field is "produced by" (or associated with) a change in the other part, and the ratio of electric and magnetic field intensities is simply the wave impedance in the medium.

Also known as the radiation-zone, the far field carries a relatively uniform wave pattern. The radiation zone is important because far fields in general fall off in amplitude by This means that the total energy per unit area at a distance r is proportional to The area of the sphere is proportional to , so the total energy passing through the sphere is constant. This means that the far-field energy actually escapes to infinite distance (it radiates).

Definitions

Summarize

Perspective

The separation of the electric and magnetic fields into components is mathematical, rather than clearly physical, and is based on the relative rates at which the amplitude of different terms of the electric and magnetic field equations diminish as distance from the radiating element increases. The amplitudes of the far-field components fall off as , the radiative near-field amplitudes fall off as , and the reactive near-field amplitudes fall off as .[a] Definitions of the regions attempt to characterize locations where the activity of the associated field components are the strongest. Mathematically, the distinction between field components is very clear, but the demarcation of the spatial field regions is subjective. All of the field components overlap everywhere, so for example, there are always substantial far-field and radiative near-field components in the closest-in near-field reactive region.

The regions defined below categorize field behaviors that are variable, even within the region of interest. Thus, the boundaries for these regions are approximate rules of thumb, as there are no precise cutoffs between them: All behavioral changes with distance are smooth changes. Even when precise boundaries can be defined in some cases, based primarily on antenna type and antenna size, experts may differ in their use of nomenclature to describe the regions. Because of these nuances, special care must be taken when interpreting technical literature that discusses far-field and near-field regions.

The term near-field region (also known as the near field or near zone) has the following meanings with respect to different telecommunications technologies:

- The close-in region of an antenna where the angular field distribution is dependent upon the distance from the antenna.

- In the study of diffraction and antenna design, the near field is that part of the radiated field that is below distances shorter than the Fraunhofer distance,[1] which is given by from the source of the diffracting edge or antenna of longitude or diameter D.

- In fiber-optic communication, the region near a source or aperture that is closer than the Rayleigh length. (Presuming a Gaussian beam, which is appropriate for fiber optics.)

Regions according to electromagnetic length

The most convenient practice is to define the size of the regions or zones in terms of fixed numbers (fractions) of wavelengths distant from the center of the radiating part of the antenna, with the clear understanding that the values chosen are only approximate and will be somewhat inappropriate for different antennas in different surroundings. The choice of the cut-off numbers is based on the relative strengths of the field component amplitudes typically seen in ordinary practice.

Electromagnetically short antennas

For antennas shorter than half of the wavelength of the radiation they emit (i.e., electromagnetically "short" antennas), the far and near regional boundaries are measured in terms of a simple ratio of the distance r from the radiating source to the wavelength λ of the radiation. For such an antenna, the near field is the region within a radius r ≪ λ, while the far-field is the region for which r ≫ 2 λ. The transition zone is the region between r = λ and r = 2 λ .

The length of the antenna, D, is not important, and the approximation is the same for all shorter antennas (sometimes idealized as so-called point antennas). In all such antennas, the short length means that charges and currents in each sub-section of the antenna are the same at any given time, since the antenna is too short for the RF transmitter voltage to reverse before its effects on charges and currents are felt over the entire antenna length.

Electromagnetically long antennas

For antennas physically larger than a half-wavelength of the radiation they emit, the near and far fields are defined in terms of the Fraunhofer distance. Named after Joseph von Fraunhofer, the following formula gives the Fraunhofer distance:

where D is the largest dimension of the radiator (or the diameter of the antenna) and λ is the wavelength of the radio wave. Either of the following two relations are equivalent, emphasizing the size of the region in terms of wavelengths λ or diameters D:

This distance provides the limit between the near and far field. The parameter D corresponds to the physical length of an antenna, or the diameter of a reflector ("dish") antenna.

Having an antenna electromagnetically longer than one-half the dominated wavelength emitted considerably extends the near-field effects, especially that of focused antennas. Conversely, when a given antenna emits high frequency radiation, it will have a near-field region larger than what would be implied by a lower frequency (i.e. longer wavelength).

Additionally, a far-field region distance dF must satisfy these two conditions.[2][clarification needed]

where D is the largest physical linear dimension of the antenna and dF is the far-field distance. The far-field distance is the distance from the transmitting antenna to the beginning of the Fraunhofer region, or far field.

Transition zone

The transition zone between these near and far field regions, extending over the distance from one to two wavelengths from the antenna,[citation needed] is the intermediate region in which both near-field and far-field effects are important. In this region, near-field behavior dies out and ceases to be important, leaving far-field effects as dominant interactions. (See the "Far Field" image above.)

Regions according to diffraction behavior

Far-field diffraction

As far as acoustic wave sources are concerned, if the source has a maximum overall dimension or aperture width (D) that is large compared to the wavelength λ, the far-field region is commonly taken to exist at distances, when the Fresnel parameter is larger than 1:[3]

For a beam focused at infinity, the far-field region is sometimes referred to as the Fraunhofer region. Other synonyms are far field, far zone, and radiation field. Any electromagnetic radiation consists of an electric field component E and a magnetic field component H. In the far field, the relationship between the electric field component E and the magnetic component H is that characteristic of any freely propagating wave, where E and H have equal magnitudes at any point in space (where measured in units where [[speed of light|c]] = 1).

Near-field diffraction

In contrast to the far field, the diffraction pattern in the near field typically differs significantly from that observed at infinity and varies with distance from the source. In the near field, the relationship between E and H becomes very complex. Also, unlike the far field where electromagnetic waves are usually characterized by a single polarization type (horizontal, vertical, circular, or elliptical), all four polarization types can be present in the near field.[4]

The near field is a region in which there are strong inductive and capacitive effects from the currents and charges in the antenna that cause electromagnetic components that do not behave like far-field radiation. These effects decrease in power far more quickly with distance than do the far-field radiation effects. Non-propagating (or evanescent) fields extinguish very rapidly with distance, which makes their effects almost exclusively felt in the near-field region.

Also, in the part of the near field closest to the antenna (called the reactive near field, see below), absorption of electromagnetic power in the region by a second device has effects that feed back to the transmitter, increasing the load on the transmitter that feeds the antenna by decreasing the antenna impedance that the transmitter "sees". Thus, the transmitter can sense when power is being absorbed in the closest near-field zone (by a second antenna or some other object) and is forced to supply extra power to its antenna, and to draw extra power from its own power supply, whereas if no power is being absorbed there, the transmitter does not have to supply extra power.

Near-field characteristics

Summarize

Perspective

The near field itself is further divided into the reactive near field and the radiative near field. The reactive and radiative near-field designations are also a function of wavelength (or distance). However, these boundary regions are a fraction of one wavelength within the near field. The outer boundary of the reactive near-field region is commonly considered to be a distance of times the wavelength (i.e., or approximately 0.159λ) from the antenna surface. The reactive near-field is also called the inductive near-field. The radiative near field (also called the Fresnel region) covers the remainder of the near-field region, from out to the Fraunhofer distance.[4]

Reactive near field, or the nearest part of the near field

In the reactive near field (very close to the antenna), the relationship between the strengths of the E and H fields is often too complicated to easily predict, and difficult to measure. Either field component (E or H) may dominate at one point, and the opposite relationship dominate at a point only a short distance away. This makes finding the true power density in this region problematic. This is because to calculate power, not only E and H both have to be measured but the phase relationship between E and H as well as the angle between the two vectors must also be known in every point of space.[4]

In this reactive region, not only is an electromagnetic wave being radiated outward into far space but there is a reactive component to the electromagnetic field, meaning that the strength, direction, and phase of the electric and magnetic fields around the antenna are sensitive to EM absorption and re-emission in this region, and respond to it. In contrast, absorption far from the antenna has negligible effect on the fields near the antenna, and causes no back-reaction in the transmitter.

Very close to the antenna, in the reactive region, energy of a certain amount, if not absorbed by a receiver, is held back and is stored very near the antenna surface. This energy is carried back and forth from the antenna to the reactive near field by electromagnetic radiation of the type that slowly changes electrostatic and magnetostatic effects. For example, current flowing in the antenna creates a purely magnetic component in the near field, which then collapses as the antenna current begins to reverse, causing transfer of the field's magnetic energy back to electrons in the antenna as the changing magnetic field causes a self-inductive effect on the antenna that generated it. This returns energy to the antenna in a regenerative way, so that it is not lost. A similar process happens as electric charge builds up in one section of the antenna under the pressure of the signal voltage, and causes a local electric field around that section of antenna, due to the antenna's self-capacitance. When the signal reverses so that charge is allowed to flow away from this region again, the built-up electric field assists in pushing electrons back in the new direction of their flow, as with the discharge of any unipolar capacitor. This again transfers energy back to the antenna current.

Because of this energy storage and return effect, if either of the inductive or electrostatic effects in the reactive near field transfer any field energy to electrons in a different (nearby) conductor, then this energy is lost to the primary antenna. When this happens, an extra drain is seen on the transmitter, resulting from the reactive near-field energy that is not returned. This effect shows up as a different impedance in the antenna, as seen by the transmitter.

The reactive component of the near field can give ambiguous or undetermined results when attempting measurements in this region. In other regions, the power density is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the antenna. In the vicinity very close to the antenna, however, the energy level can rise dramatically with only a small decrease in distance toward the antenna. This energy can adversely affect both humans and measurement equipment because of the high powers involved.[4]

Radiative near field (Fresnel region), or farthest part of the near field

The radiative near field (sometimes called the Fresnel region) does not contain reactive field components from the source antenna, since it is far enough from the antenna that back-coupling of the fields becomes out of phase with the antenna signal, and thus cannot efficiently return inductive or capacitive energy from antenna currents or charges. The energy in the radiative near field is thus all radiant energy, although its mixture of magnetic and electric components are still different from the far field. Further out into the radiative near field (one half wavelength to 1 wavelength from the source), the E and H field relationship is more predictable, but the E to H relationship is still complex. However, since the radiative near field is still part of the near field, there is potential for unanticipated (or adverse) conditions.

For example, metal objects such as steel beams can act as antennas by inductively receiving and then "re-radiating" some of the energy in the radiative near field, forming a new radiating surface to consider. Depending on antenna characteristics and frequencies, such coupling may be far more efficient than simple antenna reception in the yet-more-distant far field, so far more power may be transferred to the secondary "antenna" in this region than would be the case with a more distant antenna. When a secondary radiating antenna surface is thus activated, it then creates its own near-field regions, but the same conditions apply to them.[4]

Compared to the far field

The near field is remarkable for reproducing classical electromagnetic induction and electric charge effects on the EM field, which effects "die-out" with increasing distance from the antenna: The magnetic field component that’s in phase quadrature to electric fields is proportional to the inverse-cube of the distance () and electric field strength proportional to inverse-square of distance (). This fall-off is far more rapid than the classical radiated far-field (E and B fields, which are proportional to the simple inverse-distance (). Typically near-field effects are not important farther away than a few wavelengths of the antenna.

More-distant near-field effects also involve energy transfer effects that couple directly to receivers near the antenna, affecting the power output of the transmitter if they do couple, but not otherwise. In a sense, the near field offers energy that is available to a receiver only if the energy is tapped, and this is sensed by the transmitter by means of responding to electromagnetic near fields emanating from the receiver. Again, this is the same principle that applies in induction coupled devices, such as a transformer, which draws more power at the primary circuit, if power is drawn from the secondary circuit. This is different with the far field, which constantly draws the same energy from the transmitter, whether it is immediately received, or not.

The amplitude of other components (non-radiative/non-dipole) of the electromagnetic field close to the antenna may be quite powerful, but, because of more rapid fall-off with distance than behavior, they do not radiate energy to infinite distances. Instead, their energies remain trapped in the region near the antenna, not drawing power from the transmitter unless they excite a receiver in the area close to the antenna. Thus, the near fields only transfer energy to very nearby receivers, and, when they do, the result is felt as an extra power draw in the transmitter. As an example of such an effect, power is transferred across space in a common transformer or metal detector by means of near-field phenomena (in this case inductive coupling), in a strictly short-range effect (i.e., the range within one wavelength of the signal).

Classical EM modelling

Summarize

Perspective

Solving Maxwell's equations for the electric and magnetic fields for a localized oscillating source, such as an antenna, surrounded by a homogeneous material (typically vacuum or air), yields fields that, far away, decay in proportion to where r is the distance from the source. These are the radiating fields, and the region where r is large enough for these fields to dominate is the far field.

In general, the fields of a source in a homogeneous isotropic medium can be written as a multipole expansion.[5] The terms in this expansion are spherical harmonics (which give the angular dependence) multiplied by spherical Bessel functions (which give the radial dependence). For large r, the spherical Bessel functions decay as , giving the radiated field above. As one gets closer and closer to the source (smaller r), approaching the near field, other powers of r become significant.

The next term that becomes significant is proportional to and is sometimes called the induction term.[6] It can be thought of as the primarily magnetic energy stored in the field, and returned to the antenna in every half-cycle, through self-induction. For even smaller r, terms proportional to become significant; this is sometimes called the electrostatic field term and can be thought of as stemming from the electrical charge in the antenna element.

Very close to the source, the multipole expansion is less useful (too many terms are required for an accurate description of the fields). Rather, in the near field, it is sometimes useful to express the contributions as a sum of radiating fields combined with evanescent fields, where the latter are exponentially decaying with r. And in the source itself, or as soon as one enters a region of inhomogeneous materials, the multipole expansion is no longer valid and the full solution of Maxwell's equations is generally required.

Antennas

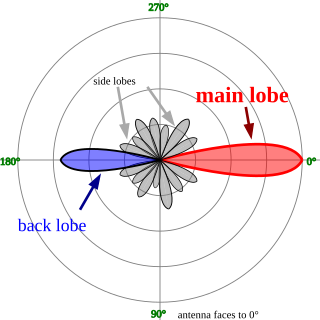

If an oscillating electrical current is applied to a conductive structure of some type, electric and magnetic fields will appear in space about that structure. If those fields are lost to a propagating space wave the structure is often termed an antenna. Such an antenna can be an assemblage of conductors in space typical of radio devices or it can be an aperture with a given current distribution radiating into space as is typical of microwave or optical devices. The actual values of the fields in space about the antenna are usually quite complex and can vary with distance from the antenna in various ways.

However, in many practical applications, one is interested only in effects where the distance from the antenna to the observer is very much greater than the largest dimension of the transmitting antenna. The equations describing the fields created about the antenna can be simplified by assuming a large separation and dropping all terms that provide only minor contributions to the final field. These simplified distributions have been termed the "far field" and usually have the property that the angular distribution of energy does not change with distance, although the energy levels still vary with distance and time. Such an angular energy distribution is usually termed an antenna pattern.

Note that, by the principle of reciprocity, the pattern observed when a particular antenna is transmitting is identical to the pattern measured when the same antenna is used for reception. Typically one finds simple relations describing the antenna far-field patterns, often involving trigonometric functions or at worst Fourier or Hankel transform relationships between the antenna current distributions and the observed far-field patterns. While far-field simplifications are very useful in engineering calculations, this does not mean the near-field functions cannot be calculated, especially using modern computer techniques. An examination of how the near fields form about an antenna structure can give great insight into the operations of such devices.

Impedance

The electromagnetic field in the far-field region of an antenna is independent of the details of the near field and the nature of the antenna. The wave impedance is the ratio of the strength of the electric and magnetic fields, which in the far field are in phase with each other. Thus, the far field "impedance of free space" is resistive and is given by:

With the usual approximation for the speed of light in free space c0 ≈ 2.9979 × 108 m/s, this gives the frequently used expression:

The electromagnetic field in the near-field region of an electrically small coil antenna is predominantly magnetic. For small values of r/ λ the impedance of a magnetic loop is low and inductive, at short range being asymptotic to:

The electromagnetic field in the near-field region of an electrically short rod antenna is predominantly electric. For small values of r/ λ the impedance is high and capacitive, at short range being asymptotic to:

In both cases, the wave impedance converges on that of free space as the range approaches the far field.

See also

Local effects

- Fraunhofer diffraction for more on the far field

- Fresnel diffraction for more on the near field

- Inductive heating of ferrous metals

- Near-field communication for more on near-field communication technology

- Near-field magnetic induction communication

- Physics of magnetic resonance imaging

- Resonant inductive coupling for magnetic device applications

- RFID often operates at near field, but newer types of tags transmit radio waves and thus operate using the far field

- Subwavelength imaging

- Wireless power transfer for some power transfer applications

Other

- Antenna measurement covers Far-Field Ranges (FF) and Near-Field Ranges (NF), separated by the Fraunhofer distance.

- Ground waves: a mode of propagation

- Inverse-square law

- Self-focusing transducers, harnessing the effect with acoustic waves

- Sky waves: a mode of propagation

Notes

References

Patents

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.