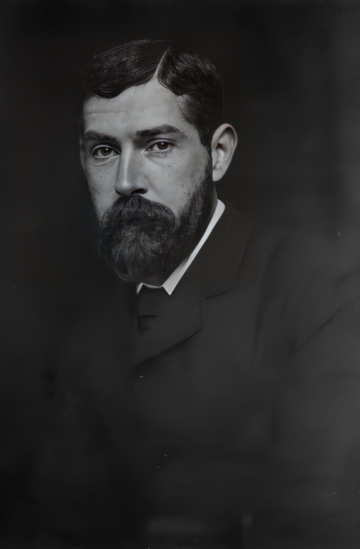

Francis Herbert Bradley OM (30 January 1846 – 18 September 1924) was a British idealist philosopher. His most important work was Appearance and Reality (1893).[2]

F. H. Bradley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Francis Herbert Bradley 30 January 1846 Clapham, England |

| Died | 18 September 1924 (aged 78) Oxford, England |

| Alma mater | University College, Oxford |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | Merton College, Oxford |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | |

Life

Bradley was born at Clapham, Surrey, England (now part of the Greater London area). He was the child of Charles Bradley, an evangelical Anglican preacher, and Emma Linton, Charles's second wife. A. C. Bradley was his brother. Educated at Cheltenham College and Marlborough College, he read, as a teenager, some of Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. In 1865, he entered University College, Oxford. In 1870, he was elected to a fellowship at Oxford's Merton College where he remained until his death in 1924.[3] Bradley is buried in Holywell Cemetery in Oxford.

During his life, Bradley was a respected philosopher and was granted honorary degrees many times. He was the first British philosopher to be awarded the Order of Merit. His fellowship at Merton College did not carry any teaching assignments and thus he was free to continue to write. He was famous for his non-pluralistic approach to philosophy. His outlook saw a monistic unity, transcending divisions between logic, metaphysics and ethics. Consistently, his own view combined monism with absolute idealism. Although Bradley did not think of himself as a Hegelian philosopher, his own unique brand of philosophy was inspired by, and contained elements of, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's dialectical method.

Philosophy

Bradley rejected the utilitarian and empiricist trends in British philosophy represented by John Locke, David Hume, and John Stuart Mill. Instead, Bradley was a leading member of the philosophical movement known as British idealism, which was strongly influenced by Kant and the German idealists Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling, and Hegel, although Bradley tended to downplay his influences.

In 1909, Bradley published an essay entitled "On Truth and Coherence" in the journal Mind (reprinted in Essays on Truth and Reality). The essay criticises a form of infallibilist foundationalism in epistemology. The philosopher Robert Stern has argued that in this paper Bradley defends coherence not as an account of justification but as a criterion or test for truth.[4]

Bradley also defends a novel theory of facts. For Bradley, facts can justify our beliefs, but no fact justifies any belief to the point where it is immune from revision. "And the view which I advocate takes them [facts] all as in principle fallible… Facts for it [his view] are true, we may say, just so far as they work, just so far as they contribute to the order of experience. … And there is no ‘fact’ which possesses an absolute right."[5] Facts of history are, for Bradley, arrived at via an inferential process. "The historical fact then (for us) is a conclusion; … For everything that we say we think we have reasons, our realities are built up of explicit or hidden inferences; in a single word, facts are inferential, and their actuality depends on the correctness of the reasoning which makes them what they are."[6]

Moral philosophy

Bradley's view of morality was driven by his criticism of the idea of self used in the current utilitarian theories of ethics.[7] He addressed the central question of "Why should I be moral?"[8]

He opposed individualism, instead defending the view of self and morality as essentially social. Bradley held that our moral duty was founded on the need to cultivate our ideal "good self" in opposition to our "bad self".[9] However, he acknowledged that society could not be the source of our moral life, of our quest to realise our ideal self. For example, some societies may need moral reform from within, and this reform is based on standards which must come from elsewhere than the standards of that society.[10]

He made the best of this admission in suggesting that the ideal self can be realised through following religion.[11]

His views of the social self in his moral theorising are relevant to the views of Fichte, George Herbert Mead, and pragmatism. They are also compatible with modern views such as those of Richard Rorty and anti-individualism approaches.[12]

Legacy

Bradley's philosophical reputation declined greatly after his death. British idealism was practically eliminated by G. E. Moore and Bertrand Russell in the early 1900s. Bradley was also famously criticised in A. J. Ayer's logical positivist work Language, Truth and Logic for making statements that do not meet the requirements of positivist verification principle; e.g., statements such as "The Absolute enters into, but is itself incapable of, evolution and progress." There has in recent years, however, been a resurgence of interest in Bradley's and other idealist philosophers' work in the Anglo-American academic community.[13]

In 1914, a then-unknown T. S. Eliot wrote his dissertation for a PhD from the Department of Philosophy at Harvard University on Bradley. It was entitled Knowledge and Experience in the Philosophy of F. H. Bradley. Due to tensions leading up to and starting the First World War, Eliot was unable to return to Harvard for his oral defence, resulting in the university never conferring the degree. Nevertheless, Bradley remained an influence on Eliot's poetry.[14]

Books and publications

- The Presuppositions of Critical History (1874), Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1968. (1874 edition)

- Ethical Studies, (1876), Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927, 1988. (1876 edition)

- The Principles of Logic (1883), London: Oxford University Press, 1922. (Volume 1)/(Volume 2)

- Appearance and Reality (1893), London: S. Sonnenschein; New York: Macmillan. (1916 edition)

- Essays on Truth and Reality, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1914.

- Aphorisms, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1930.

- Collected Essays, vols. 1–2, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1935.

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.