Limit (category theory)

Mathematical concept From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In category theory, a branch of mathematics, the abstract notion of a limit captures the essential properties of universal constructions such as products, pullbacks and inverse limits. The dual notion of a colimit generalizes constructions such as disjoint unions, direct sums, coproducts, pushouts and direct limits.

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2013) |

Limits and colimits, like the strongly related notions of universal properties and adjoint functors, exist at a high level of abstraction. In order to understand them, it is helpful to first study the specific examples these concepts are meant to generalize.

Definition

Summarize

Perspective

Limits and colimits in a category are defined by means of diagrams in . Formally, a diagram of shape in is a functor from to :

The category is thought of as an index category, and the diagram is thought of as indexing a collection of objects and morphisms in patterned on .

One is most often interested in the case where the category is a small or even finite category. A diagram is said to be small or finite whenever is.

Limits

Let be a diagram of shape in a category . A cone to is an object of together with a family of morphisms indexed by the objects of , such that for every morphism in , we have .

A limit of the diagram is a cone to such that for every cone to there exists a unique morphism such that for all in .

One says that the cone factors through the cone with the unique factorization . The morphism is sometimes called the mediating morphism.

Limits are also referred to as universal cones, since they are characterized by a universal property (see below for more information). As with every universal property, the above definition describes a balanced state of generality: The limit object has to be general enough to allow any cone to factor through it; on the other hand, has to be sufficiently specific, so that only one such factorization is possible for every cone.

Limits may also be characterized as terminal objects in the category of cones to F.

It is possible that a diagram does not have a limit at all. However, if a diagram does have a limit then this limit is essentially unique: it is unique up to a unique isomorphism. For this reason one often speaks of the limit of F.

Colimits

The dual notions of limits and cones are colimits and co-cones. Although it is straightforward to obtain the definitions of these by inverting all morphisms in the above definitions, we will explicitly state them here:

A co-cone of a diagram is an object of together with a family of morphisms

for every object of , such that for every morphism in , we have .

A colimit of a diagram is a co-cone of such that for any other co-cone of there exists a unique morphism such that for all in .

Colimits are also referred to as universal co-cones. They can be characterized as initial objects in the category of co-cones from .

As with limits, if a diagram has a colimit then this colimit is unique up to a unique isomorphism.

Variations

Limits and colimits can also be defined for collections of objects and morphisms without the use of diagrams. The definitions are the same (note that in definitions above we never needed to use composition of morphisms in ). This variation, however, adds no new information. Any collection of objects and morphisms defines a (possibly large) directed graph . If we let be the free category generated by , there is a universal diagram whose image contains . The limit (or colimit) of this diagram is the same as the limit (or colimit) of the original collection of objects and morphisms.

Weak limit and weak colimits are defined like limits and colimits, except that the uniqueness property of the mediating morphism is dropped.

Examples

Limits

The definition of limits is general enough to subsume several constructions useful in practical settings. In the following we will consider the limit (L, φ) of a diagram F : J → C.

- Terminal objects. If J is the empty category there is only one diagram of shape J: the empty one (similar to the empty function in set theory). A cone to the empty diagram is essentially just an object of C. The limit of F is any object that is uniquely factored through by every other object. This is just the definition of a terminal object.

- Products. If J is a discrete category then a diagram F is essentially nothing but a family of objects of C, indexed by J. The limit L of F is called the product of these objects. The cone φ consists of a family of morphisms φX : L → F(X) called the projections of the product. In the category of sets, for instance, the products are given by Cartesian products and the projections are just the natural projections onto the various factors.

- Powers. A special case of a product is when the diagram F is a constant functor to an object X of C. The limit of this diagram is called the Jth power of X and denoted XJ.

- Equalizers. If J is a category with two objects and two parallel morphisms from one object to the other, then a diagram of shape J is a pair of parallel morphisms in C. The limit L of such a diagram is called an equalizer of those morphisms.

- Kernels. A kernel is a special case of an equalizer where one of the morphisms is a zero morphism.

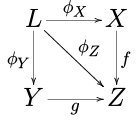

- Pullbacks. Let F be a diagram that picks out three objects X, Y, and Z in C, where the only non-identity morphisms are f : X → Z and g : Y → Z. The limit L of F is called a pullback or a fiber product. It can nicely be visualized as a commutative square:

- Inverse limits. Let J be a directed set (considered as a small category by adding arrows i → j if and only if i ≥ j) and let F : Jop → C be a diagram. The limit of F is called an inverse limit or projective limit.

- If J = 1, the category with a single object and morphism, then a diagram of shape J is essentially just an object X of C. A cone to an object X is just a morphism with codomain X. A morphism f : Y → X is a limit of the diagram X if and only if f is an isomorphism. More generally, if J is any category with an initial object i, then any diagram of shape J has a limit, namely any object isomorphic to F(i). Such an isomorphism uniquely determines a universal cone to F.

- Topological limits. Limits of functions are a special case of limits of filters, which are related to categorical limits as follows. Given a topological space X, denote by F the set of filters on X, x ∈ X a point, V(x) ∈ F the neighborhood filter of x, A ∈ F a particular filter and the set of filters finer than A and that converge to x. The filters F are given a small and thin category structure by adding an arrow A → B if and only if A ⊆ B. The injection becomes a functor and the following equivalence holds :

- x is a topological limit of A if and only if A is a categorical limit of

Colimits

Examples of colimits are given by the dual versions of the examples above:

- Initial objects are colimits of empty diagrams.

- Coproducts are colimits of diagrams indexed by discrete categories.

- Copowers are colimits of constant diagrams from discrete categories.

- Coequalizers are colimits of a parallel pair of morphisms.

- Cokernels are coequalizers of a morphism and a parallel zero morphism.

- Pushouts are colimits of a pair of morphisms with common domain.

- Direct limits are colimits of diagrams indexed by directed sets.

Properties

Summarize

Perspective

Existence of limits

A given diagram F : J → C may or may not have a limit (or colimit) in C. Indeed, there may not even be a cone to F, let alone a universal cone.

A category C is said to have limits of shape J if every diagram of shape J has a limit in C. Specifically, a category C is said to

- have products if it has limits of shape J for every small discrete category J (it need not have large products),

- have equalizers if it has limits of shape (i.e. every parallel pair of morphisms has an equalizer),

- have pullbacks if it has limits of shape (i.e. every pair of morphisms with common codomain has a pullback).

A complete category is a category that has all small limits (i.e. all limits of shape J for every small category J).

One can also make the dual definitions. A category has colimits of shape J if every diagram of shape J has a colimit in C. A cocomplete category is one that has all small colimits.

The existence theorem for limits states that if a category C has equalizers and all products indexed by the classes Ob(J) and Hom(J), then C has all limits of shape J.[1]: §V.2 Thm.1 In this case, the limit of a diagram F : J → C can be constructed as the equalizer of the two morphisms[1]: §V.2 Thm.2

given (in component form) by

There is a dual existence theorem for colimits in terms of coequalizers and coproducts. Both of these theorems give sufficient and necessary conditions for the existence of all (co)limits of shape J.

Universal property

Limits and colimits are important special cases of universal constructions.

Let C be a category and let J be a small index category. The functor category CJ may be thought of as the category of all diagrams of shape J in C. The diagonal functor

is the functor that maps each object N in C to the constant functor Δ(N) : J → C to N. That is, Δ(N)(X) = N for each object X in J and Δ(N)(f) = idN for each morphism f in J.

Given a diagram F: J → C (thought of as an object in CJ), a natural transformation ψ : Δ(N) → F (which is just a morphism in the category CJ) is the same thing as a cone from N to F. To see this, first note that Δ(N)(X) = N for all X implies that the components of ψ are morphisms ψX : N → F(X), which all share the domain N. Moreover, the requirement that the cone's diagrams commute is true simply because this ψ is a natural transformation. (Dually, a natural transformation ψ : F → Δ(N) is the same thing as a co-cone from F to N.)

Therefore, the definitions of limits and colimits can then be restated in the form:

- A limit of F is a universal morphism from Δ to F.

- A colimit of F is a universal morphism from F to Δ.

Adjunctions

Like all universal constructions, the formation of limits and colimits is functorial in nature. In other words, if every diagram of shape J has a limit in C (for J small) there exists a limit functor

which assigns each diagram its limit and each natural transformation η : F → G the unique morphism lim η : lim F → lim G commuting with the corresponding universal cones. This functor is right adjoint to the diagonal functor Δ : C → CJ. This adjunction gives a bijection between the set of all morphisms from N to lim F and the set of all cones from N to F

which is natural in the variables N and F. The counit of this adjunction is simply the universal cone from lim F to F. If the index category J is connected (and nonempty) then the unit of the adjunction is an isomorphism so that lim is a left inverse of Δ. This fails if J is not connected. For example, if J is a discrete category, the components of the unit are the diagonal morphisms δ : N → NJ.

Dually, if every diagram of shape J has a colimit in C (for J small) there exists a colimit functor

which assigns each diagram its colimit. This functor is left adjoint to the diagonal functor Δ : C → CJ, and one has a natural isomorphism

The unit of this adjunction is the universal cocone from F to colim F. If J is connected (and nonempty) then the counit is an isomorphism, so that colim is a left inverse of Δ.

Note that both the limit and the colimit functors are covariant functors.

As representations of functors

One can use Hom functors to relate limits and colimits in a category C to limits in Set, the category of sets. This follows, in part, from the fact the covariant Hom functor Hom(N, –) : C → Set preserves all limits in C. By duality, the contravariant Hom functor must take colimits to limits.

If a diagram F : J → C has a limit in C, denoted by lim F, there is a canonical isomorphism

which is natural in the variable N. Here the functor Hom(N, F–) is the composition of the Hom functor Hom(N, –) with F. This isomorphism is the unique one which respects the limiting cones.

One can use the above relationship to define the limit of F in C. The first step is to observe that the limit of the functor Hom(N, F–) can be identified with the set of all cones from N to F:

The limiting cone is given by the family of maps πX : Cone(N, F) → Hom(N, FX) where πX(ψ) = ψX. If one is given an object L of C together with a natural isomorphism Φ : Hom(L, –) → Cone(–, F), the object L will be a limit of F with the limiting cone given by ΦL(idL). In fancy language, this amounts to saying that a limit of F is a representation of the functor Cone(–, F) : C → Set.

Dually, if a diagram F : J → C has a colimit in C, denoted colim F, there is a unique canonical isomorphism

which is natural in the variable N and respects the colimiting cones. Identifying the limit of Hom(F–, N) with the set Cocone(F, N), this relationship can be used to define the colimit of the diagram F as a representation of the functor Cocone(F, –).

Interchange of limits and colimits of sets

Let I be a finite category and J be a small filtered category. For any bifunctor

there is a natural isomorphism

In words, filtered colimits in Set commute with finite limits. It also holds that small colimits commute with small limits.[2]

Functors and limits

Summarize

Perspective

If F : J → C is a diagram in C and G : C → D is a functor then by composition (recall that a diagram is just a functor) one obtains a diagram GF : J → D. A natural question is then:

- “How are the limits of GF related to those of F?”

Preservation of limits

A functor G : C → D induces a map from Cone(F) to Cone(GF): if Ψ is a cone from N to F then GΨ is a cone from GN to GF. The functor G is said to preserve the limits of F if (GL, Gφ) is a limit of GF whenever (L, φ) is a limit of F. (Note that if the limit of F does not exist, then G vacuously preserves the limits of F.)

A functor G is said to preserve all limits of shape J if it preserves the limits of all diagrams F : J → C. For example, one can say that G preserves products, equalizers, pullbacks, etc. A continuous functor is one that preserves all small limits.

One can make analogous definitions for colimits. For instance, a functor G preserves the colimits of F if G(L, φ) is a colimit of GF whenever (L, φ) is a colimit of F. A cocontinuous functor is one that preserves all small colimits.

If C is a complete category, then, by the above existence theorem for limits, a functor G : C → D is continuous if and only if it preserves (small) products and equalizers. Dually, G is cocontinuous if and only if it preserves (small) coproducts and coequalizers.

An important property of adjoint functors is that every right adjoint functor is continuous and every left adjoint functor is cocontinuous. Since adjoint functors exist in abundance, this gives numerous examples of continuous and cocontinuous functors.

For a given diagram F : J → C and functor G : C → D, if both F and GF have specified limits there is a unique canonical morphism

which respects the corresponding limit cones. The functor G preserves the limits of F if and only if this map is an isomorphism. If the categories C and D have all limits of shape J then lim is a functor and the morphisms τF form the components of a natural transformation

The functor G preserves all limits of shape J if and only if τ is a natural isomorphism. In this sense, the functor G can be said to commute with limits (up to a canonical natural isomorphism).

Preservation of limits and colimits is a concept that only applies to covariant functors. For contravariant functors the corresponding notions would be a functor that takes colimits to limits, or one that takes limits to colimits.

Lifting of limits

A functor G : C → D is said to lift limits for a diagram F : J → C if whenever (L, φ) is a limit of GF there exists a limit (L′, φ′) of F such that G(L′, φ′) = (L, φ). A functor G lifts limits of shape J if it lifts limits for all diagrams of shape J. One can therefore talk about lifting products, equalizers, pullbacks, etc. Finally, one says that G lifts limits if it lifts all limits. There are dual definitions for the lifting of colimits.

A functor G lifts limits uniquely for a diagram F if there is a unique preimage cone (L′, φ′) such that (L′, φ′) is a limit of F and G(L′, φ′) = (L, φ). One can show that G lifts limits uniquely if and only if it lifts limits and is amnestic.

Lifting of limits is clearly related to preservation of limits. If G lifts limits for a diagram F and GF has a limit, then F also has a limit and G preserves the limits of F. It follows that:

- If G lifts limits of all shape J and D has all limits of shape J, then C also has all limits of shape J and G preserves these limits.

- If G lifts all small limits and D is complete, then C is also complete and G is continuous.

The dual statements for colimits are equally valid.

Creation and reflection of limits

Let F : J → C be a diagram. A functor G : C → D is said to

- create limits for F if whenever (L, φ) is a limit of GF there exists a unique cone (L′, φ′) to F such that G(L′, φ′) = (L, φ), and furthermore, this cone is a limit of F.

- reflect limits for F if each cone to F whose image under G is a limit of GF is already a limit of F.

Dually, one can define creation and reflection of colimits.

The following statements are easily seen to be equivalent:

- The functor G creates limits.

- The functor G lifts limits uniquely and reflects limits.

There are examples of functors which lift limits uniquely but neither create nor reflect them.

Examples

- Every representable functor C → Set preserves limits (but not necessarily colimits). In particular, for any object A of C, this is true of the covariant Hom functor Hom(A,–) : C → Set.

- The forgetful functor U : Grp → Set creates (and preserves) all small limits and filtered colimits; however, U does not preserve coproducts. This situation is typical of algebraic forgetful functors.

- The free functor F : Set → Grp (which assigns to every set S the free group over S) is left adjoint to forgetful functor U and is, therefore, cocontinuous. This explains why the free product of two free groups G and H is the free group generated by the disjoint union of the generators of G and H.

- The inclusion functor Ab → Grp creates limits but does not preserve coproducts (the coproduct of two abelian groups being the direct sum).

- The forgetful functor Top → Set lifts limits and colimits uniquely but creates neither.

- Let Metc be the category of metric spaces with continuous functions for morphisms. The forgetful functor Metc → Set lifts finite limits but does not lift them uniquely.

A note on terminology

Older terminology referred to limits as "inverse limits" or "projective limits", and to colimits as "direct limits" or "inductive limits". This has been the source of a lot of confusion.

There are several ways to remember the modern terminology. First of all,

- cokernels,

- coproducts,

- coequalizers, and

- codomains

are types of colimits, whereas

- kernels,

- products

- equalizers, and

- domains

are types of limits. Second, the prefix "co" implies "first variable of the ". Terms like "cohomology" and "cofibration" all have a slightly stronger association with the first variable, i.e., the contravariant variable, of the bifunctor.

See also

- Cartesian closed category – Type of category in category theory

- Equaliser (mathematics) – Set of arguments where two or more functions have the same value

- Inverse limit – Construction in category theory

- Product (category theory) – Generalized object in category theory

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.