Loading AI tools

EU-wide goods and services tax policy From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

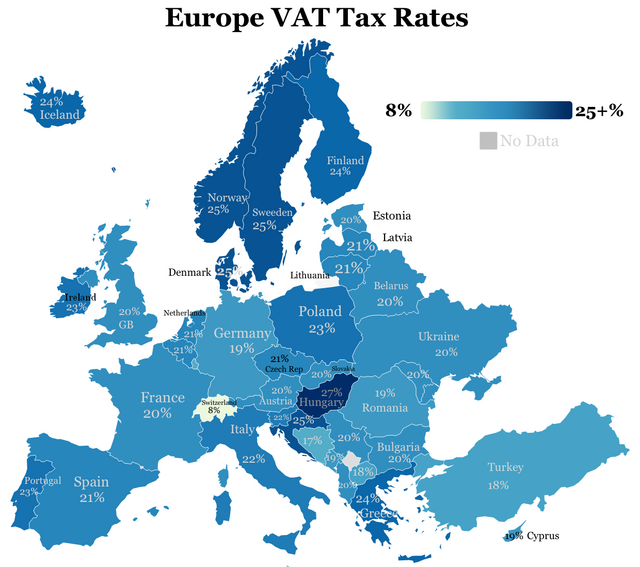

The European Union value-added tax (or EU VAT) is a value added tax on goods and services within the European Union (EU). The EU's institutions do not collect the tax, but EU member states are each required to adopt in national legislation a value added tax that complies with the EU VAT code. Different rates of VAT apply in different EU member states, ranging from 17% in Luxembourg to 27% in Hungary. The total VAT collected by member states is used as part of the calculation to determine what each state contributes to the EU's budget.

German industrialist Wilhelm von Siemens proposed the concept of a value-added tax in 1918 to replace the German turnover tax however, the turnover tax was not replaced until 1968.[1] The modern variation of VAT was first implemented by Maurice Lauré, joint director of the French tax authority, who implemented VAT on 10 April 1954 in France's Ivory Coast colony. Assessing the experiment as successful, France introduced it domestically in 1958.[2]

Following creation of the European Economic Community in 1957, the Fiscal and Financial Committee set up by the European Commission in 1960 under the chairmanship of Professor Fritz Neumark made its priority objective the elimination of distortions to competition caused by disparities in national indirect tax systems.[3][4]

The Neumark Report published in 1962 concluded that France's VAT model would be the simplest and most effective indirect tax system. This led to the EEC issuing two VAT directives, adopted in April 1967, providing a blueprint for introducing VAT across the EEC, following which, other member states (initially Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany) introduced VAT.[1]

The First Directive was concerned with harmonising the legislation of the member states with respect to turnover taxes. This act was to replace the multi-level cumulative indirect taxation system in the EU member states by simplifying tax calculations and neutralising the indirect taxation factor in relation to competition in the EU.

The EU value-added tax is based on the "destination principle": the value-added tax is paid to the government of the country in which the consumer who buys the product lives. Businesses selling a product charge the VAT and the customer pays it. When the customer is a business, the VAT is known as an "input VAT." When a consumer purchases the end product from a business, the tax is called the "output VAT."

A value-added tax collected at each stage in the supply chain is remitted to the tax authorities of the member state concerned and forms part of that state's revenue. A small proportion goes to the European Union in the form of a levy ("VAT-based own resources").

The co-ordinated administration of value-added tax within the EU VAT area is an important part of the single market. A cross-border VAT is declared in the same way as domestic VAT, which facilitates the elimination of border controls between member states, saving costs and reducing delays. It also simplifies administrative work for freight forwarders. Previously, in spite of the customs union, the differing VAT rates and the separate VAT administration processes resulted in a high administrative and cost burden for cross-border trade.

For private individuals (not registered for VAT) who transport to one member state goods purchased while living or traveling in another member state, the VAT is normally payable in the state where the goods were purchased, regardless of any differences in VAT rates between the two states, and any tax payable on distance sales is collected by the seller.[citation needed] However, there are a number of special provisions for particular goods and services.

The EU VAT system is regulated by a series of European Union directives.

The aim of the EU VAT directive (Council Directive 2006/112/EC of 28 November 2006 on the common system of value-added tax) is to harmonize VATs within the EU VAT area and specifies that VAT rates must be above a certain limit.[5]: 97,99 It has several basic purposes:[citation needed]

The VAT directive is published in all EU official languages.[5]

In 1977, the Council of the European Communities sought to harmonise the national VAT systems of its member states by issuing the Sixth Directive to provide a uniform basis of assessment and replacing the Second Directive promulgated in 1967.[6]

The Sixth Directive defined a taxable transaction within the EU VAT scheme as a transaction involving the supply of goods,[7] the supply of services,[8] and the importation of goods.[9]

The Eighth Directive, adopted in 1979, focuses on harmonising the legislation of the member states with respect to turnover taxes—provisions on the reimbursement of value added tax to taxable persons not established on the territory of the country (the provisions of this act allow a taxpayer of one member state to receive a VAT refund in another member state).[1]

Businesses can be required to register for VAT in EU member states other than the one in which they are based if they supply goods via mail order to those states over a certain threshold. Businesses established in one member state but receive supplies in another member state may be able to reclaim VAT charged in the second state.[10] To do so, businesses have a value added tax identification number.

The Thirteenth VAT Directive, adopted in 1986, allows businesses established outside the EU to recover VAT in certain circumstances.[11][1]

In 2006, the Council sought to improve on the Sixth Directive by recasting it.[12]

The recast of the Sixth Directive retained all of the legal provisions of the Sixth Directive but also incorporated VAT provisions found in other Directives and rearranged text order to make it more readable.[13] In addition, the Recast Directive codified certain other instruments including a Commission decision of 2000 relating to funding of the EU budget from with a percentage of the VAT amounts collected by each member state.[14]

Abuse criteria are identified by the jurisprudence of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) developed from 2006 onwards: VAT cases of Halifax and University of Huddersfield, and subsequently Part Service, Ampliscientifica and Amplifin, Tanoarch, Weald Leasing and RBS Deutschland.[15] EU member states are under a duty to make their anti-abuse laws and rules compliant with the ECJ decisions, besides to retroactively re-characterize and prosecute transactions which meet those ECJ criteria.[15]

The accrual of an undue tax advantage may be even found under a formal application of the Sixth Directive and shall be based on a variety of objective factors highlighting that the "organization structure and the form transactions" freely chosen by the taxpayer are essentially aimed to carry out a tax advantage which is contrary to the purposes of the EU Sixth Directive.[15]

Such a jurisprudence implies an implicit judicial evaluation of the organizational structure chosen by the entrepreneurs and investors operating across multiple EU member states, in order to establish if the organization was appropriately ordered and necessary to their economic activities or "had the purpose of limiting their tax burdens". It is in contrast with the constitutional right to the freedom of entrepreneurship.[clarification needed]

A domestic supply of goods is a taxable transaction where goods are received in exchange for consideration within one member state.[16] One member state then charges VAT on the goods and allows a corresponding credit upon resale.

An Intra-Community acquisition of goods is a taxable transaction for consideration crossing two or more member states.[17] The place of supply is determined to be the destination member state, and VAT is normally charged at the rate applicable in the destination member state;[18] however there are special provisions for distance selling (see below).

The mechanism for achieving this result is as follows: the exporting member state does not collect VAT on the sale, but still gives the exporting merchant a credit for the VAT paid on the purchase by the exporter (in practice this often means a cash refund) ("zero-rating"). The importing member state "reverse charges" the VAT. In other words, the importer is required to pay VAT to the importing member state at its rate. In many cases a credit is immediately given for this as input VAT. The importer then charges VAT on resale normally.[18]

When a vendor in one member state sells goods directly to individuals and VAT-exempt organisations in another member state and the aggregate value of goods sold to consumers in that member state is below €100,000 or €35,000 (or the equivalent) in any 12 consecutive months, that sale of goods may qualify for a distance sales treatment.[19] Distance sales treatment allowed the vendor to apply domestic place of supply rules for determining which member state collects the VAT.[19] This allows VAT to be charged at the rate applicable in the exporting member state. However, there are some additional restrictions to be met: certain goods do not qualify (e.g., new motor vehicles),[20] and a compulsory VAT registration is required for a supplier of excise goods such as tobacco and alcohol to the U.K.

If sales to final consumers in a member state exceeded €100,000, the exporting vendor is required to charge VAT at the rate applicable in the importing member state. If a supplier provides a distant sales service to several EU member states, a separate accounting of sold goods in regards to VAT calculation was required. The supplier must then seek a VAT registration (and charge applicable rate) in each country where the volume of sales in any 12 consecutive months exceeds the local threshold.

A special threshold amount of €35,000 was allowed if the importing member states fears that without the lower threshold amount competition within the member state would be distorted.[19] Only Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands applied the higher €100,000 threshold.

A supply of services is the supply of anything that is not a good.[21]

The general rule for determining the place of supply is the place where the supplier of the services is established (or "belongs"), such as a fixed establishment where the service is supplied, the supplier's permanent address, or where the supplier usually resides.[22] VAT is charged at the rate applicable in and collected by the member state where the place of supply of the services is located.[22]

This general rule for the place of supply of services (the place where the supplier is established) is subject to several exceptions if the services are supplied to customers established outside the Community, or to taxable persons established in the Community but not in the same country as the supplier. Most exceptions switch the place of supply to the place of receipt. Supply exceptions include:

Miscellaneous services include:

The place of real estate-related services is where the real estate is located.[22]

There are special rules for determining the place of electronically delivered supply of services.

The mechanism for collecting VAT when the place of supply is not in the same member state as the supplier is similar to that used for the Intra-Community Acquisitions of goods; zero-rating by the supplier and reverse charge by the recipient of the services for taxable persons. But if the recipient of the services is not a taxable person (i.e. a final consumer), the supplier must generally charge VAT at the rate applicable in its own member state.

If the place of supply is outside the EU, no VAT is charged.

Goods imported from non-member states are subject to VAT at the rate applicable in the importing member state, whether or not the goods are received for consideration and the importer.[23] VAT is generally charged at the border, at the same time as customs duty and uses the price determined by customs.[24] However, as a result of EU administrative VAT relief, an exception called Low Value Consignment Relief is allowed on low-value shipments.

VAT paid on importation is treated as input VAT in the same way as domestic purchases.

Following changes introduced on 1 July 2003, non-EU businesses providing digital electronic commerce and entertainment products and services to EU countries are required to register with the tax authorities in the relevant EU member state, and to collect VAT on their sales at the appropriate rate according to the location of the purchaser.[25] Alternatively, under a special scheme, non-EU and non-digital-goods[26] businesses may register and account for VAT on only one EU member state.[25] This produces distortions as the rate of VAT is that of the member state being registered to, not where the customer is located, and an alternative approach is therefore under negotiation where VAT is charged at the rate of the member state where the purchaser is located.[25]

There is a distinction between goods and services which are exempt from VAT and those which are subject to 0% VAT. The seller of exempt goods and services is not entitled to reclaim input VAT on business purchases, whereas the seller of goods and services rated at 0% is entitled.[27]

For example, a book manufacturer in Ireland who purchases paper including VAT at the 23% rate[28] and sells books at the 0% rate[29] is entitled to reclaim the VAT on the purchase of paper, as the business is making taxable supplies. In countries like Sweden and Finland, non-profit organisations such as sports clubs are exempt from all VAT, and have to pay full VAT for purchases without reimbursement.[30][citation needed][clarification needed] Additionally, in Malta, the purchase of food for human consumption from supermarkets, grocers etc., the purchase of pharmaceutical products, school tuition fees and scheduled bus service fares are exempted from VAT.[31] The EU commission wants to abolish or reduce the scope of exemptions.[32] There are objections from sports federations since this would create cost and a lot of bureaucracy for voluntary staff.[33]

A VAT group is a grouping of companies or organisations who are permitted to treat themselves as a single unit for purposes related to the collection and payment of VAT. Article 11 of the Directive permits member states to decide whether to allow groups of closely linked companies or organisations to be treated as a single "taxable person", and if so, also to implement its own measures decided to combat any associated tax avoidance or evasion arising from misuse of the provision. The group members must be 'closely related' e.g. a principal company and its subsidiaries, and should register jointly for VAT purposes. VAT does not need to be levied on the costs of transactions undertaken within the group.[34]

Article 11 reads:

After consulting the advisory committee on value added tax (hereafter, the ‘VAT Committee’), each Member State may regard as a single taxable person any persons established in the territory of that Member State who, while legally independent, are closely bound to one another by financial, economic and organisational links. A Member State exercising the option provided for in the first paragraph, may adopt any measures needed to prevent tax evasion or avoidance through the use of this provision.[5]

Requirements vary between EU states which have opted to allow VAT groups because the EU legislation provides for member states to determine their own detailed rules for group eligibility and operations.

Italian tax legislation permits the operation of VAT Groups,[35]

All bodies (whether companies or limited liability partnerships) within the group are jointly and severally liable for all VAT due.[36]

To comply with the rules introduced since 2006, from 1 October 2014, businesses needed to decide if they want to register to use the EU VAT Mini One Stop Shop (MOSS) simplification scheme.[37] If suppliers decided against the MOSS, registration was required in each Member State where business-to-consumer (B2C) supplies of e-services are made. With no minimum turnover threshold for the new EU VAT rules, VAT registration was required regardless of the value of e-service supply in each Member State. Since 1 July 2021, the MOSS has been extended to B2C goods and turned into a One Stop Shop (OSS):[38]

Some goods and services are "zero-rated", though the term is not used in the Directive. The Directive refers to "exemptions" with or without refund of VAT charged at the preceding stage (see 2006/112/EC Article 110). In the U.K., examples include some food, books, and medications, along with certain kinds of transport. The Directive does provide for very limited mandatory "zero-rates", generally related to supplies if an international nature such as exports and international transportation where the exemptions has a right of deduction (2006/112/EC Article 169). However, generally it was intended that the minimum VAT rate throughout Europe would be 5%. However, zero-rating remains in some member states e.g. Ireland, as a legacy of pre-EU legislation (permitted by Article 110). These member states have been granted a derogation to continue existing zero-rating but are not permitted to add new goods or services. An EU member state may uplift their domestic zero rate to a higher rate, for example to 5% or 20%; however, EU VAT rules do not allow a reversal back to the zero rate once it has been given up. Member states may institute a reduced rate on a previously zero-rated item even where EU law does not provide for a reduced rate. On the other hand, if a member state makes an increase from a zero-rate to the prevalent standard rate, they may not decrease to a reduced rate unless specifically provided for in EU VAT Law (the Annex III of 2006/112/EC list sets out where a reduced rate is permissible).

Different rates of VAT apply in different EU member states. The lowest standard rate of VAT throughout the EU is 17%,[citation needed] although member states can apply two reduced rates of VAT (not below 5%) to certain goods and services.[5]: 98–99 Certain goods and services are required to be exempt from VAT (for example, postal services, medical care, lending, insurance, betting),[5]: 135 and certain other goods and services may be exempt from VAT ("zero rated") although individual EU member states may opt to charge VAT on those supplies (such as land and certain financial services)[5]: 137 . Input VAT that is attributable to exempt supplies is not recoverable.

| Jurisdiction | Rate (Standard) | Rate (Reduced) | Abbr. | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20% | 13% or 10% | MwSt.; USt. | German: Mehrwertsteuer / Umsatzsteuer | |

| 21%[39] | 12% or 6% | BTW; TVA; MWSt | Dutch: Belasting over de toegevoegde waarde; French: Taxe sur la Valeur Ajoutée; German: Mehrwertsteuer | |

| 20% | 9%[40] | ДДС | Bulgarian: Данък върху добавената стойност (Danăk vărhu dobavenata stojnost) | |

| 19%[41] | 9% or 5%[40] | ΦΠΑ | Greek: Φόρος Προστιθέμενης Αξίας (Fóros Prastithémenes Axías) | |

| 21% | 12% | DPH | Czech: Daň z přidané hodnoty | |

| 25% | 13% or 5% | PDV | Croatian: Porez na dodanu vrijednost | |

| 25% | none | moms | Danish: Meromsætningsafgift | |

| 22%[42] | 9% or 5% | km | Estonian: käibemaks | |

| 25.5%[43] | 14% or 10% | ALV; Moms | Finnish: Arvonlisävero; Swedish: Mervärdesskatt | |

| 20% | 10%, 5.5%, or 2.1% | TVA | French: Taxe sur la valeur ajoutée | |

| 19%[45][46] | 7%[45][46] | MwSt.; USt. | German: Mehrwertsteuer / Umsatzsteuer | |

| 24%[47] | 13% or 6%[48] | ΦΠΑ | Greek: Φόρος Προστιθέμενης Αξίας (Fóros Prostithémenis Axías) | |

| 27% | 18% or 5%[40] | ÁFA | Hungarian: általános forgalmi adó | |

| 23%[49] | 13.5%, 9%, 4.8%, or 0% | VAT; CBL | English: Value Added Tax; Irish: Cáin Bhreisluacha | |

| 22%[50] | 10%, 5%, or 4%[51] | IVA | Italian: Imposta sul Valore Aggiunto | |

| 21%[52] | 12% or 5% | PVN | Latvian: Pievienotās vērtības nodoklis | |

| 21% | 9% or 5% | PVM | Lithuanian: Pridėtinės vertės mokestis | |

| 17%[53] | 14%, 8%, or 3% | TVA | French: Taxe sur la Valeur Ajoutée | |

| 18% | 7%, 5% or 0%[40] | VAT | Maltese: Taxxa fuq il-Valur Miżjud; English: Value Added Tax | |

| 21%[54] | 9% or 0% | BTW | Dutch: Belasting toegevoegde waarde / Omzetbelasting | |

| 23% | 8%, 5%,[40] and 0%[55] | PTU; VAT | Polish: Podatek od towarów i usług | |

| IVA | Portuguese: Imposto sobre o Valor Acrescentado | |||

| 19% | 9%, 8%, or 5%[40] | TVA | Romanian: Taxa pe valoarea adăugată | |

| 20% | 10% | DPH | Slovak: Daň z pridanej hodnoty | |

| 22% | 9.5% or 5% | DDV | Slovene: Davek na dodano vrednost | |

| 21%[58] | 10% or 4%[58] | IVA | Spanish: Impuesto sobre el valor añadido | |

| 25% | 12% or 6% | Moms | Swedish: Mervärdesskatt |

The EU VAT area is a territory consisting of all member states of the European Union and certain other countries which follow the European Union's (EU) rules on VAT.[59][60] The principle is also valid for some special taxes on products like alcohol and tobacco.

All EU member states are part of the VAT area. However some areas of member states are exempt areas:

Included with the Republic of Cyprus at its 19% rate:

Included with France at its 20% rate:

Applies the United Kingdom 20% rate:

Finland:

France:

Germany:

Greece:

Italy:

Spain:

France:

Other nations:

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.