Douglas Hofstadter

American professor of cognitive science (born 1945) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Douglas Richard Hofstadter (born February 15, 1945) is an American cognitive and computer scientist whose research includes concepts such as the sense of self in relation to the external world,[1][4] consciousness, analogy-making, strange loops, artificial intelligence, and discovery in mathematics and physics. His 1979 book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction,[5][6] and a National Book Award (at that time called The American Book Award) for Science.[7][note 1] His 2007 book I Am a Strange Loop won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Science and Technology.[8][9][10][11]

Douglas Hofstadter | |

|---|---|

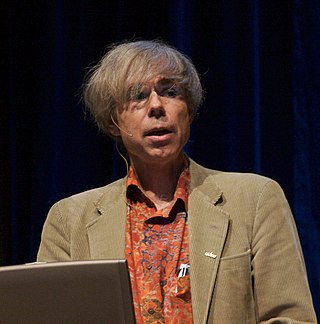

Hofstadter in 2006 | |

| Born | Douglas Richard Hofstadter February 15, 1945 New York City, US |

| Education | Stanford University (BS) University of Oregon (PhD) |

| Known for | Gödel, Escher, Bach I Am a Strange Loop[1] Hofstadter's butterfly Hofstadter's law |

| Spouse(s) | Carol Ann Brush (1985–1993; her death) Baofen Lin (2012–present) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | National Book Award Pulitzer Prize Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement[2] |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Cognitive science Philosophy of mind Artificial intelligence Physics |

| Institutions | Indiana University Stanford University University of Oregon University of Michigan |

| Thesis | The Energy Levels of Bloch Electrons in a Magnetic Field (1975) |

| Doctoral advisor | Gregory Wannier[3] |

| Doctoral students | David Chalmers Robert M. French Scott A. Jones Melanie Mitchell |

| Website | cogs.sitehost.iu.edu/.. |

Early life and education

Hofstadter was born in New York City to future Nobel Prize-winning physicist Robert Hofstadter and Nancy Givan Hofstadter.[12] He grew up on the campus of Stanford University, where his father was a professor, and attended the International School of Geneva in 1958–59. He graduated with distinction in mathematics from Stanford University in 1965, and received his Ph.D. in physics[3][13] from the University of Oregon in 1975, where his study of the energy levels of Bloch electrons in a magnetic field led to his discovery of the fractal known as Hofstadter's butterfly.[13]

Academic career

Summarize

Perspective

Hofstadter was initially appointed to Indiana University's computer science department faculty in 1977, and at that time he launched his research program in computer modeling of mental processes (which he called "artificial intelligence research", a label he has since dropped in favor of "cognitive science research"). In 1984, he moved to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he was hired as a professor of psychology and was also appointed to the Walgreen Chair for the Study of Human Understanding.

In 1988, Hofstadter returned to IU as College of Arts and Sciences Professor in cognitive science and computer science. He was also appointed adjunct professor of history and philosophy of science, philosophy, comparative literature, and psychology, but has said that his involvement with most of those departments is nominal.[14][15][16]

Since 1988, Hofstadter has been the College of Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor of Cognitive Science and Comparative Literature at Indiana University in Bloomington, where he directs the Center for Research on Concepts and Cognition, which consists of himself and his graduate students, forming the "Fluid Analogies Research Group" (FARG).[17] In 1988, he received the In Praise of Reason award, the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry's highest honor.[18] In 2009, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[19] and became a member of the American Philosophical Society.[20] In 2010, he was elected a member of the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala, Sweden.[21]

Work and publications

Summarize

Perspective

At the University of Michigan and Indiana University, Hofstadter and Melanie Mitchell coauthored a computational model of "high-level perception"—Copycat—and several other models of analogy-making and cognition, including the Tabletop project, co-developed with Robert M. French.[22] The Letter Spirit project, implemented by Gary McGraw and John Rehling, aims to model artistic creativity by designing stylistically uniform "gridfonts" (typefaces limited to a grid). Other more recent models include Phaeaco (implemented by Harry Foundalis) and SeqSee (Abhijit Mahabal), which model high-level perception and analogy-making in the microdomains of Bongard problems and number sequences, respectively, as well as George (Francisco Lara-Dammer), which models the processes of perception and discovery in triangle geometry.[23][24][25]

Hofstadter's thesis about consciousness, first expressed in Gödel, Escher, Bach but also present in several of his later books, is that it is "an emergent consequence of seething lower-level activity in the brain."[citation needed] In Gödel, Escher, Bach he draws an analogy between the social organization of a colony of ants and the mind seen as a coherent "colony" of neurons. In particular, Hofstadter claims that our sense of having (or being) an "I" comes from the abstract pattern he terms a "strange loop", an abstract cousin of such concrete phenomena as audio and video feedback that Hofstadter has defined as "a level-crossing feedback loop". The prototypical example of a strange loop is the self-referential structure at the core of Gödel's incompleteness theorems. Hofstadter's 2007 book I Am a Strange Loop carries his vision of consciousness considerably further, including the idea that each human "I" is distributed over numerous brains, rather than being limited to one.[26] Le Ton beau de Marot: In Praise of the Music of Language is a long book devoted to language and translation, especially poetry translation, and one of its leitmotifs is a set of 88 translations of "Ma Mignonne", a highly constrained poem by 16th-century French poet Clément Marot. In this book, Hofstadter jokingly describes himself as "pilingual" (meaning that the sum total of the varying degrees of mastery of all the languages that he has studied comes to 3.14159 ...), as well as an "oligoglot" (someone who speaks "a few" languages).[27][28]

In 1999, the bicentennial year of the Russian poet and writer Alexander Pushkin, Hofstadter published a verse translation of Pushkin's classic novel-in-verse Eugene Onegin. He has translated other poems and two novels: La Chamade (That Mad Ache) by Françoise Sagan, and La Scoperta dell'Alba (The Discovery of Dawn) by Walter Veltroni, the then-head of the Partito Democratico in Italy. The Discovery of Dawn was published in 2007, and That Mad Ache was published in 2009, bound together with Hofstadter's essay "Translator, Trader: An Essay on the Pleasantly Pervasive Paradoxes of Translation".[citation needed]

Hofstadter's Law

Hofstadter's Law is "It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter's Law." The law is stated in Gödel, Escher, Bach.

Students

Hofstadter's former Ph.D. students[29] include (with dissertation title):

- David Chalmers – Toward a Theory of Consciousness

- Bob French – Tabletop: An Emergent, Stochastic Model of Analogy-Making

- Gary McGraw – Letter Spirit (Part One): Emergent High-level Perception of Letters Using Fluid Concepts

- Melanie Mitchell – Copycat: A Computer Model of High-Level Perception and Conceptual Slippage in Analogy-making

Public image

Summarize

Perspective

Hofstadter has said that he feels "uncomfortable with the nerd culture that centers on computers". He admits that "a large fraction [of his audience] seems to be those who are fascinated by technology", but when it was suggested that his work "has inspired many students to begin careers in computing and artificial intelligence" he replied that he was pleased about that, but that he himself has "no interest in computers".[30][31] In that interview he also mentioned a course he has twice given at Indiana University, in which he took a "skeptical look at a number of highly touted AI projects and overall approaches".[16] For example, upon the defeat of Garry Kasparov by Deep Blue, he commented: "It was a watershed event, but it doesn't have to do with computers becoming intelligent."[32] In his book Metamagical Themas, he says that "in this day and age, how can anyone fascinated by creativity and beauty fail to see in computers the ultimate tool for exploring their essence?"[33]

In 1988, Dutch director Piet Hoenderdos created a docudrama about Hofstadter and his ideas, Victim of the Brain, based on The Mind's I. It includes interviews with Hofstadter about his work.[34]

Provoked by predictions of a technological singularity (a hypothetical moment in the future of humanity when a self-reinforcing, runaway development of artificial intelligence causes a radical change in technology and culture), Hofstadter has both organized and participated in several public discussions of the topic. At Indiana University in 1999 he organized such a symposium, and in April 2000, he organized a larger symposium titled "Spiritual Robots" at Stanford University, in which he moderated a panel consisting of Ray Kurzweil, Hans Moravec, Kevin Kelly, Ralph Merkle, Bill Joy, Frank Drake, John Holland and John Koza. Hofstadter was also an invited panelist at the first Singularity Summit, held at Stanford in May 2006. Hofstadter expressed doubt that the singularity will occur in the foreseeable future.[35][36][37][38][39][40]

In a 2023 interview, Hofstadter said that rapid progress in AI made some of his "core beliefs" about AI's limitations "collapse".[41][42] Hinting at an AI takeover, he added that human beings may soon be eclipsed by "something else that is far more intelligent and will become incomprehensible to us".[43][44]

Columnist

Summarize

Perspective

When Martin Gardner retired from writing his "Mathematical Games" column for Scientific American magazine, Hofstadter succeeded him in 1981–83 with a column titled Metamagical Themas (an anagram of "Mathematical Games"). An idea he introduced in one of these columns was the concept of "Reviews of This Book", a book containing nothing but cross-referenced reviews of itself that has an online implementation.[45] One of Hofstadter's columns in Scientific American concerned the damaging effects of sexist language, and two chapters of his book Metamagical Themas are devoted to that topic, one of which is a biting analogy-based satire, "A Person Paper on Purity in Language" (1985), in which the reader's presumed revulsion at racism and racist language is used as a lever to motivate an analogous revulsion at sexism and sexist language; Hofstadter published it under the pseudonym William Satire, an allusion to William Safire.[46] Another column reported on the discoveries made by University of Michigan professor Robert Axelrod in his computer tournament pitting many iterated prisoner's dilemma strategies against each other, and a follow-up column discussed a similar tournament that Hofstadter and his graduate student Marek Lugowski organized.[citation needed] The "Metamagical Themas" columns ranged over many themes, including patterns in Frédéric Chopin's piano music (particularly his études), the concept of superrationality (choosing to cooperate when the other party/adversary is assumed to be equally intelligent as oneself), and the self-modifying game of Nomic, based on the way the legal system modifies itself, and developed by philosopher Peter Suber.[47]

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

Hofstadter was married to Carol Ann Brush until her death. They met in Bloomington, and married in Ann Arbor in 1985. They had two children. Carol died in 1993 from the sudden onset of a brain tumor, glioblastoma multiforme, when their children were young. The Carol Ann Brush Hofstadter Memorial Scholarship for Bologna-bound Indiana University students was established in 1996 in her name.[48] Hofstadter's book Le Ton beau de Marot is dedicated to their two children and its dedication reads "To M. & D., living sparks of their Mommy's soul". In 2010, Hofstadter met his second wife, Baofen Lin, in a cha-cha-cha class. They married in 2012 in Bloomington.[49][50]

Hofstadter has composed pieces for piano and for piano and voice. He created an audio CD, DRH/JJ, of these compositions performed mostly by pianist Jane Jackson, with a few performed by Brian Jones, Dafna Barenboim, Gitanjali Mathur, and Hofstadter.[51]

The dedication for I Am A Strange Loop is: "To my sister Laura, who can understand, and to our sister Molly, who cannot."[52] Hofstadter explains in the preface that his younger sister Molly never developed the ability to speak or understand language.[53]

As a consequence of his attitudes about consciousness and empathy, Hofstadter became a vegetarian in his teenage years, and has remained primarily so since that time.[54][55]

In popular culture

In the 1982 novel 2010: Odyssey Two, Arthur C. Clarke's first sequel to 2001: A Space Odyssey, HAL 9000 is described by the character "Dr. Chandra" as being caught in a "Hofstadter–Möbius loop". The movie uses the term "H. Möbius loop". On April 3, 1995, Hofstadter's book Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought was the first book sold by Amazon.com.[56] Michael R. Jackson's musical A Strange Loop makes reference to Hofstadter's concept and the title of his 2007 book.

Published works

Summarize

Perspective

Books

The books published by Hofstadter are (the ISBNs refer to paperback editions, where available):

- Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid (ISBN 0-465-02656-7) (1979)

- Metamagical Themas (ISBN 0-465-04566-9) (collection of Scientific American columns and other essays, all with postscripts) (1985)

- Ambigrammi: un microcosmo ideale per lo studio della creatività (ISBN 88-7757-006-7) (in Italian only)

- Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies (co-authored with several of Hofstadter's graduate students) (ISBN 0-465-02475-0)

- Rhapsody on a Theme by Clement Marot (ISBN 0-910153-11-6) (1995, published 1996; volume 16 of series The Grace A. Tanner Lecture in Human Values)

- Le Ton beau de Marot: In Praise of the Music of Language (ISBN 0-465-08645-4)

- I Am a Strange Loop (ISBN 0-465-03078-5) (2007)

- Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking, co-authored with Emmanuel Sander (ISBN 0-465-01847-5) (first published in French as L'Analogie. Cœur de la pensée; published in English in the U.S. in April 2013)

Involvement in other books

Hofstadter has written forewords for or edited the following books:

- The Mind's I: Fantasies and Reflections on Self and Soul (co-edited with Daniel Dennett), 1981. (ISBN 0-465-03091-2, ISBN 0-553-01412-9) and (ISBN 0-553-34584-2)

- Inversions, by Scott Kim, 1981. (Foreword) (ISBN 1-55953-280-7)

- Alan Turing: The Enigma by Andrew Hodges, 1983. (Preface)

- Sparse Distributed Memory by Pentti Kanerva, Bradford Books/MIT Press, 1988. (Foreword) (ISBN 0-262-11132-2)

- Are Quanta Real? A Galilean Dialogue by J.M. Jauch, Indiana University Press, 1989. (Foreword) (ISBN 0-253-20545-X)

- Gödel's Proof (2002 revised edition) by Ernest Nagel and James R. Newman, edited by Hofstadter. In the foreword, Hofstadter explains that the book (originally published in 1958) exerted a profound influence on him when he was young. (ISBN 0-8147-5816-9)

- Who Invented the Computer? The Legal Battle That Changed Computing History by Alice Rowe Burks, 2003. (Foreword)

- Alan Turing: Life and Legacy of a Great Thinker by Christof Teuscher, 2003. (editor)

- Brainstem Still Life by Jason Salavon, 2004. (Introduction) (ISBN 981-05-1662-2)

- Masters of Deception: Escher, Dalí & the Artists of Optical Illusion by Al Seckel, 2004. (Foreword)

- King of Infinite Space: Donald Coxeter, the Man Who Saved Geometry by Siobhan Roberts, Walker and Company, 2006. (Foreword)

- Exact Thinking in Demented Times: The Vienna Circle and the Epic Quest for the Foundations of Science by Karl Sigmund, Basic Books, 2017. Hofstadter wrote the foreword and helped with the translation.

- To Light the Flame of Reason: Clear Thinking for the Twenty-First Century by Christopher Sturmark, Prometheus, 2022. (Foreword and Contributions)

Translations

- Eugene Onegin: A Novel Versification from the Russian original of Alexander Pushkin, 1999. (ISBN 0-465-02094-1)

- The Discovery of Dawn from the Italian original of Walter Veltroni, 2007. (ISBN 978-0-8478-3109-8)

- That Mad Ache, co-bound with Translator, Trader: An Essay on the Pleasantly Pervasive Paradoxes of Translation, from the French original La chamade of Francoise Sagan), 2009. (ISBN 978-0-465-01098-1)

See also

Notes

- Gödel, Escher, Bach won the 1980 award for hardcover science.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.