Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

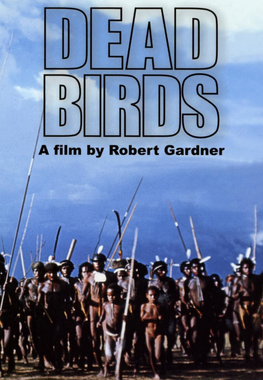

Dead Birds (1963 film)

American documentary film by Robert Gardner From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Dead Birds is a 1963 American documentary film by Robert Gardner about the ritual warfare cycle of the Dugum Dani people who live in the Baliem Valley in present-day Highland Papua province (then a part of Papua province known as Irian Jaya) on the western half of the island of New Guinea in Indonesia.[1] The film presents footage of battles between the Willihiman-Wallalua confederation (Wiligima-Alula) of Gutelu alliance (Kurulu) and the Wittaia alliance (Wita Waya) with scenes of the funeral of a small boy killed by a raiding party, the women's work that goes on while battles continue, and the wait for enemy to appear.[2] In 1964 the film received the Grand Prize "Marzocco d'Oro" at the 5th Festival dei Popoli rassegna internazionale del film etnografico e sociologico ("Festival of the Peoples International Film Festival") in Florence, Italy, the Robert J. Flaherty Award given by the City College of New York, and was a featured film at the Melbourne Film Festival (now Melbourne International Film Festival).[3][4][5][6] In 1998, Dead Birds was included in the annual selection of 25 motion pictures added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress, being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and recommended for preservation.[7][8] Dead Birds has come to hold canonical status among ethnographic films.[9][10][11]

Remove ads

Remove ads

Synopsis

Summarize

Perspective

The film's theme is the encounter that all people must have with death, as told in a Dugum Dani myth of the origins of death that bookends the film.[12] The film uses a nonlinear narrative structure of parallel or braided narrative that traces three individuals through a season of three deaths and one near-death as relayed by an expository voiceover that describes scenes and the thoughts of the film's protagonists.[13][11] The film's establishing shot, an extreme long shot, tilts and pans over the Baliem valley from left to right, following the flight of a bird across the village, its cultivated fields, and the fighting ground.[10] A voiceover describes the great race between a bird and a snake which was to determine the lives of human beings: Should men shed their skins and live forever like snakes, or die like birds? The bird won: the fate of humans is death. Abruptly the sounds and sights of a funeral envelope the screen.[14] Weyak, an adult man, farms, guards the frontier, and creates a complex knotted strap that will be presented to another at a funeral as Laca (or Laka), his wife, harvests sweet potatoes and goes to make salt with other women of the community.[15] The small boy Pua tends pigs, explores nature, and plays with his friends. Enemy announce their intentions and the men come to the fighting ground, while the women continue to the salt grounds and Pua plays and tends his pigs. One fighter is wounded, it begins to rain, and the battle ends.[15] Dead Birds now focuses on the relationship of the living to the ghosts and the rituals that placate them and keep them away from the village. As a pig ritual is planned and pigs are slaughtered, news comes that Pua's little friend Weyakhe has been killed.[15] The next sequence details Weyakhe's funeral ceremony.[15] Laca receives the funeral strap: Weyak does not want to touch it. He heads to his guard tower. In the distance, the enemy dance to celebrate this victory over Weyak's group.[10] The victory does not last long, for Weyak's people kill a man who tried to steal a pig. Now the victors celebrate with their own dance. Scenes of the celebration are intercut with those of Weyak completing his weaving. As dusk closes in the camera and voiceover lingers on the celebration, on birds, and death.[2]

Remove ads

Production

Summarize

Perspective

Robert Gardner sought to film the last days of indigenous warfare in western New Guinea and accordingly organized the Harvard-Peabody Expedition (1961–65) which brought together a multidisciplinary team to collect data on various aspects of war and culture in the Baliem Valley of western New Guinea.[16][17] In addition to filmmaker Gardner, team members included Jan Broekhuijse (anthropologist), Karl Heider (anthropologist), Peter Matthiesson (naturalist), and Michael Rockefeller (sound).[16][18] Gardner carried out the filming from the team's arrival in early 1961 while Rockefeller captured samples of wild sound for later use, as the filming did not use the then-new synchronous sound technology. Gardner composed the film narrative and edited the raw footage into the film after his return to the United States in August, 1961.[18] The sound used in the film was post-synchronized from Rockefeller's samples along with the added voiceover and composed narrative of the film.[19] In line with similar works of ethnographic film at this time, some of the scenes in the film were composed out of shots filmed at different times.[20]

Companion works

Research conducted for the film and in conjunction with it resulted in several companion works and related publications by Gardner and members of the Harvard-Peabody Expedition. Robert Gardner and Karl Heider's book Gardens of War detailed the filmmaking and aspects of Dani culture relating to the film's themes .[18] A recent work by Gardner and Charles Warren described the making of this film.[21] Karl G. Heider authored The Dani of West Irian: an Ethnographic Companion to the Film Dead Birds, ethnographic monographs, and film shorts.[22][23][24] Peter Matthiessen separately wrote about the Dugum Dani and Baliem Valley in his book Under the Mountain Wall: a Chronicle of Two Seasons in the Stone Age.[25][26]

Remove ads

Background

Dead Birds reflects the concerns of anthropology emergent by the early 1960s relating to the practice of warfare in non-state level societies.[9][27] The film also fits the-then dominant paradigm of structural-functionalism that emphasized demonstrating how diverse characteristics fit into the larger pattern of the culture.[28] Dead Birds has been taken to exemplify the approach of anthropological holism as it knits together small and seemingly insignificant moments and actions, with those of great cultural significance.[29]

Release

The film was first shown at an evening meeting of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences held at the Cohen Arts Center at Tufts University, Boston, on Nov. 13, 1963.[30][31][32] It was first distributed by Contemporary Films at 267 West 25th Street, New York.[33]

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

Since the film's release, some reviewers have praised filmmaker Gardner's presentation as poetic and cinematographic, while others have criticized it as lacking a clear scientific and ethnographic focus.[11][34] Reviewers have frequently remarked on its evocation of a Dani fable and its supporting shots of birds.[12] The most-noted visual is the long take of a bird soaring over the Baliem Valley that is the film's establishing shot.[35] Reviewers point out that the film foregrounds Dugum Dani understandings of the world.[36] Others complained that the film gave short shrift to data on the culture such as the kinship system and food production.[37] Though stylistically impressive, Dead Birds has been criticized with respect to its authenticity. The characters who speak in the film are never subtitled, and even then the voice itself is not always what it seems. What the audience perceives as Weyak's voice is actually a post-filming dub of Karl G. Heider speaking Dani. Gardner himself did not speak Dani, and so all his interpretations of events are second-hand. The battle sequences are made up of many shots taken during different battles and stitched together to give the appearance of temporal unity. The apparent continuity stems from the post-synchronized sound, and in fact all the sound in the film is post-synched. Heider, himself, admits in his book Ethnographic Film, that some of the battle films were edited out of sequence, intercut with a scene of the women at the salt pool, which was filmed at a different time than the battle sequences.[20]

Remove ads

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads