DX (Digital indeX) encoding is a standard for marking 35 mm and APS photographic film and film cartridges, originally introduced by Kodak in 1983. It includes multiple markings, which are a latent image barcode on the bottom edge of the film, below the sprocket holes, a conductive pattern on the cartridge used by automatic cameras, and a barcode on the cartridge read by photo-finishing machines.

The DX encoding system was incorporated into ANSI PH1.14, which provided standards for 135 film magazines for still picture cameras and was superseded by NAPM IT1.14 in 1994; it is now part of ISO standard 1007, whose latest revision was issued in 2000.

History

In order to simplify the handling of 35 mm film in 135 format cartridges, Kodak introduced the DX encoding method on 3 January 1983.[1][2] In contrast to the film speed encoding method developed by Fuji in 1977,[3] which used electrical contacts for film speed detection on 135 format cartridges,[4] Kodak's DX encoding system immediately met success in the marketplace.

The first DX encoded film to be released was the color print film Kodacolor VR 1000 in March 1983.

The first point-and-shoot cameras to use DX encoding to automatically set film speed were released in 1984, including the Pentax Super Sport 35 / PC 35AF-M[5] and Minolta AF-E / Freedom II.[6] The first single-lens reflex cameras to take advantage of DX encoding were released in 1985, including the Konica TC-X SLR (1985),[7] Pentax A3 / A3000,[8] Minolta 7000[9] (February 1985) and 9000 (September 1985), and the Nikon F-301 / N2000.

DX-iX (data exchange - information exchange) is an expanded DX encoding system introduced in 1996 which was released as part of the Advanced Photo System (APS), which use a different cartridge and film size, also known as IX240 film. APS film and cameras were marketed with numerous brand names, most including an "ix" to emphasize the information exchange aspect, including Advantix (Kodak) and Nexia (Fujifilm).

In 1998, Fujifilm introduced a film identification system for 120 and 220 format roll film called Barcode System (with logo "|||B"). The barcode encoding the film format and length as well as the film speed and type is located on the sticker between the emulsion carrying film and the backing paper.[10][11][12][13][14] This 13-bit barcode[10][11][12][13][14] is optically scanned by newer medium format cameras like the Fujifilm GA645i Professional, GA645Wi Professional, GA645Zi Professional, GX645AF Professional, GX680III Professional, GX680IIIS Professional, Hasselblad H1, H2, H2F and H3D Model I with HM 16-32 as well as by the Contax 645 AF.[10]

Implementation

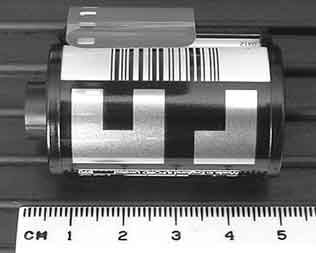

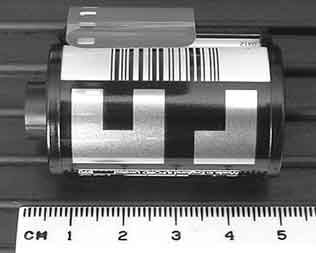

DX cartridge barcode

Next to the film exit lip is an Interleaved 2 of 5 barcode and a printed number. The six digits represent the I3A assigned DX number (middle four digits), the number of exposures (last digit) and a proprietary manufacturer's code (first digit). The DX number identifies the manufacturer, film type, and by inference, the necessary developing process type. This is used by automatic photo-finishing machines to correctly process the exposed film.[15]

DX film edge barcode

Below the sprockets under each frame of 135 film is the DX film edge barcode. The barcode is invisible until the film has been developed. It is optically imprinted as a latent image during manufacturing. The barcode is used by photo finishers to identify each frame for printing. It consists of two parallel linear barcodes, one for a synchronizing clock called the "clock track", and the other encoding film data such as type, manufacturer and frame number, called the "data track".[15] The barcode nearest the film edge (away from the sprocket holes) contains the data track. The data track sequence repeats every half frame, beginning with six start bits, followed by seven bits of DX Number Part 1, one unassigned bit, four bits of DX Number Part 2, a seven-bit frame/half-frame number, one unassigned bit, one parity bit, and finishes with four stop bits.[16] The seven-bit frame/half-frame number is called the "DXN" number (different than the "DX Number Part 1" and "DX Number Part 2"), and is an extension on the original DX edge code, patented by Eastman Kodak in 1990.[15][17]

Some image processing software utilized by film scanners allow selection of film manufacturer and type to provide automatic color correction. Interpreting the DX film edge barcode may provide this information, permitting accurate color correction to be applied.

DX Camera Auto Sensing

- 1: Ground

- 2–6: Film speed

- 7: Ground

- 8–10: Film length

- 11–12: Exposure latitude

The outside of film cartridges are marked with a DX Camera Auto Sensing (CAS) code readable by many cameras. Cameras can then automatically determine the film speed, number of exposures and exposure tolerance.

With 135 film cartridges, the DX Camera Auto Sensing code uses a 2×6 grid of rectangular contact areas on the side of the metal cartridge surface; these areas are either conductive (bare metal) or non-conductive (painted). The left-most area of both rows (with the spool post on the left) are common (ground) and are thus always bare metal. Electrical contacts in the camera read the bit pattern. Diagramatically (with spool post to the left):

| G | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 |

| G | L1 | L2 | L3 | T1 | T2 |

In this scheme:

- "G" are the two common-ground contacts

- "Sx" are the film speed contacts

- "Lx" are the film length contacts

- "Tx" are the exposure tolerance contacts

Most cameras read the film speed only, which is in the first row. Some cameras aimed at the consumer market only read enough bits in the first row to distinguish the most common film speeds. For example, 100, 200, 400, and 800 can be distinguished by reading only S1, S2, and ground.

Film speed

The five bits after the ground contact in the top row can be encoded to a maximum of 32 different film speeds, but only the 24 speeds from ISO 25/15° to 5000/38°, inclusive, spaced in intervals of 1⁄3 step, are used.

The film speed codes are in binary order if the first three bits (S1, S2, S3) are considered to identify a trio of film speeds and the last two bits (S4 and S5) are considered an adjustment of +0, +1⁄3, or +2⁄3 stops within that trio. For example, ISO speed 25/15° is encoded as 00010, while 32/16° is 00001 and 40/17° is 00011. These share a common encoding of 000xx for the first three bits, differing only in the last two bits, so 000xx designates the trio of speeds (25-32-40). Similarly, the next group of three speeds are encoded 10010 (50/18°), 10001 (64/19°), and 10011 (80/20°); it is clear from examination these all (ISO 50-64-80) share the same 100xx encoding for the first three bits. By comparison to the preceding set of three speeds, the encoding for 25/15° (00010) and 50/18° (10010) have the same xxx10 encoding for the last two bits; likewise, 32/16° (00001) and 64/19° (10001) share the xxx01 encoding, which indicates +1⁄3 stop compared to the xxx10 encoding, and 40/17° (00011) and 80/20° (10011) share the xxx11 encoding, which indicates +2⁄3 stop compared to the xxx10 encoding.

Film length

In the second row, the first three bits represent eight possible film lengths, although in practice only 12, 20, 24 and 36 exposures are encoded.

Exposure tolerance

The remaining two bits of the second row give four ranges of exposure tolerance, or latitude.

The complete encoding scheme is illustrated in the truth table below using letters and color.

- "G" is ground

- "T" represents the contact is connected to ground

- "F" represents the contact is disconnected from ground

| Film speed (ISO) |

1st row DX contacts | Film speed (ISO) |

1st row DX contacts | Film speed (ISO) |

1st row DX contacts | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | G | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | G | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | |||||

| 25/15° | G | F | F | F | T | F | 32/16° | G | F | F | F | F | T | 40/17° | G | F | F | F | T | T | ||

| 50/18° | G | T | F | F | T | F | 64/19° | G | T | F | F | F | T | 80/20° | G | T | F | F | T | T | ||

| 100/21° | G | F | T | F | T | F | 125/22° | G | F | T | F | F | T | 160/23° | G | F | T | F | T | T | ||

| 200/24° | G | T | T | F | T | F | 250/25° | G | T | T | F | F | T | 320/26° | G | T | T | F | T | T | ||

| 400/27° | G | F | F | T | T | F | 500/28° | G | F | F | T | F | T | 640/29° | G | F | F | T | T | T | ||

| 800/30° | G | T | F | T | T | F | 1000/31° | G | T | F | T | F | T | 1250/32° | G | T | F | T | T | T | ||

| 1600/33° | G | F | T | T | T | F | 2000/34° | G | F | T | T | F | T | 2500/35° | G | F | T | T | T | T | ||

| 3200/36° | G | T | T | T | T | F | 4000/37° | G | T | T | T | F | T | 5000/38° | G | T | T | T | T | T | ||

| ISO speed | 1st row DX contacts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | |

| custom 1 | G | F | F | F | F | F |

| custom 2 | G | T | F | F | F | F |

| custom 3 | G | F | T | F | F | F |

| custom 4 | G | T | T | F | F | F |

| custom 5 | G | F | F | T | F | F |

| custom 6 | G | T | F | T | F | F |

| custom 7 | G | F | T | T | F | F |

| custom 8 | G | T | T | T | F | F |

| Exposures | 2nd row DX contacts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | L1 | L2 | L3 | T1 | T2 | |

| other | G | F | F | F | ||

| 12 | G | T | F | F | ||

| 20 | G | F | T | F | ||

| 24 | G | T | T | F | ||

| 36 | G | F | F | T | ||

| 48 | G | T | F | T | ||

| 60 | G | F | T | T | ||

| 72 | G | T | T | T | ||

| Exposure tolerance (in f-stops) |

2nd row DX contacts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | L1 | L2 | L3 | T1 | T2 | |

| ±½ | G | F | F | |||

| ±1 | G | T | F | |||

| +2 −1 | G | F | T | |||

| +3 −1 | G | T | T | |||

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.